November 12th, 1944. Camp Papago Park, Arizona. The siren cut through the desert night like a scream. Flood lights snapped on across the compound, turning dust into gold and shadow into spotlight. Three prisoners were missing from evening roll call. The guards scrambled to their posts. Rifles clicked. Dogs barked.

The entire camp locked down in minutes. But this wasn’t a tunnel escape. This wasn’t a desperate flight toward freedom. What happened next would baffle military command and reveal something profound about human nature. Even in the darkest chapters of war, the three boys who vanished weren’t running from captivity.

They were running towards something far more dangerous. Normaly. By November 1944, the United States held over 370,000 Axis prisoners of war across hundreds of camps. Camp Papago Park, 15 mi northeast of Phoenix, housed some of the most unusual captives of the entire conflict. Not hardened SS officers or battlecard veterans, boys.

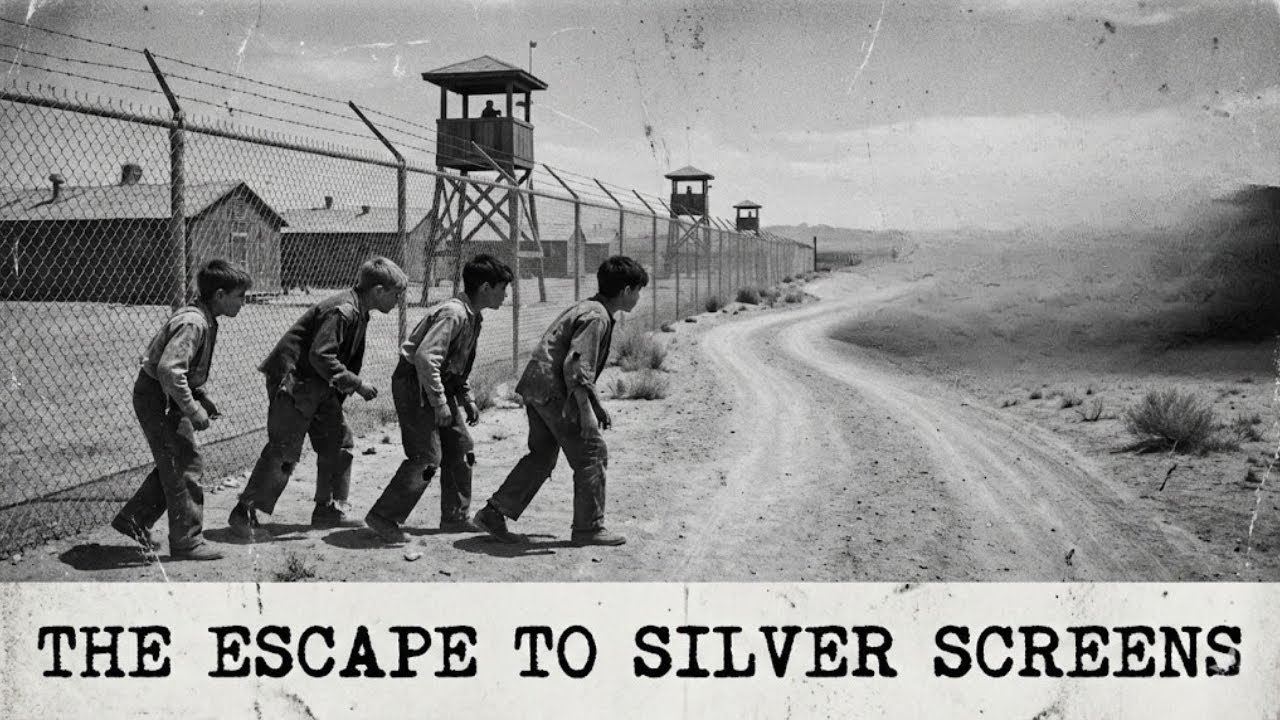

Some as young as 15 when they were conscripted into the vermach or luftwafa captured in North Africa, Sicily or Italy, they arrived in Arizona sunburned and holloweyed, still wearing uniforms that hung loose on teenage frames. The camp sprawled across 40 acres of scrubland and creassote bush. Rows of tar paper barracks baked under relentless sun.

Guard towers punctuated the perimeter like sentinels. But this wasn’t a brutal prison. Geneva Convention rules applied strictly. Prisoners received three meals daily, medical care, even educational opportunities. The American guards were mostly older men or those deemed unfit for combat overseas. Many treated the young prisoners with something bordering on pity.

Among the captives were Hans Miller, age 16, Friedrich Becker, 17, and Curt Hoffman, barely 15. All three had been captured within weeks of each other in the Italian campaign of 1943. Hans had been a radio operator who’d never fired his rifle in combat. Friedrich was a mechanic’s assistant who spent more time fixing trucks than fighting.

Kurt had been drafted from a Hitler youth camp just 4 months before his capture. They weren’t warriors. They were children wearing soldiers clothes. The three became friends in the strange limbo of Camp Papago Park. They shared a barracks with 40 other prisoners. They worked in the camp gardens under supervision.

They played cards in the evenings and wrote censored letters home that rarely received replies. Europe felt like another planet. The war seemed distant, almost abstract, filtered through weeks old newspapers and radio broadcasts in English they barely understood. But on Saturdays, the local town of Scottsdale came alive. Movie theaters on Main Street showed double features.

Families lined up for popcorn and soda. Teenagers laughed and held hands in the warm Arizona evenings. The prisoners could hear music drifting from town when the wind blew east. They could see the glow of street lights against the distant hills. It was a glimpse of a world they’d almost forgotten existed. Hans was the first to suggest it.

“A joke, really?” whispered after lights out. “What if we just walked into town? What if we saw a movie?” Friedrich laughed it off. Curt said it was insane. But the idea took root like a seed in parched soil. It grew quietly, secretly, nourished by boredom and longing. Not longing for Germany or home, longing for something simpler.

Two hours in the dark, watching heroes and villains flicker across a silver screen. The perimeter fence wasn’t as formidable as it looked. Guard patrols followed predictable patterns. The desert beyond offered cover in the twilight hours, and critically, none of the three boys wanted to actually escape. They weren’t planning to disappear into Mexico or make a desperate run for the coast.

They just wanted to be kids again for one night. Then they’d come back. November 12th arrived like any other day. Morning roll call at dawn. Work detail in the garden. Lunch of beans and cornbread. Afternoon classes in English taught by a sympathetic left tenant. Then evening formation as the sun bled red across the sonor and sky.

Hans stood in line, heart hammering. Friedrich’s hands shook slightly. Kurt whispered a silent prayer in German. When the guards turned to count the northern barracks, the three boys slipped behind the mesh hall. They moved fast and low through the shadows. The fence loomed ahead, chainlink topped with barbed wire. But near the southeastern corner, where erosion had created a shallow wash, the fence had a gap, just large enough for a skinny teenager to squeeze through, Hans went first, then Friedrich. Finally, Kurt.

They belly crawled through gravel and sand, then sprinted for the creasso bushes 30 yards beyond. No shouts, no gunfire, just the sound of their own breathing and the distant wine of cicadas. They crouched in the desert scrub, waiting for their eyes to adjust to the darkness. Behind them, the siren began to wail.

The guards discovered the absence within minutes. Sergeant William Clayton, a 42-year-old veteran of the First War, counted the line three times before accepting the impossible. Three prisoners missing. He grabbed the emergency phone. The alarm shrieked across the compound. Flood lights blazed to life. Dogs strained at their leashes.

Within 15 minutes, every guard station was manned and armed. Camp Commandant Colonel Harold Davies received the news in his office. His face went pale. Escaped prisoners meant investigations, press scrutiny, potential court marshal. He ordered an immediate lockdown. All remaining prisoners confined to barracks.

Search teams deployed, local police notified. The FBI field office in Phoenix put on alert, but the three boys heard none of this. They were already a mile away, jogging through the desert toward the distant lights of Scottsdale. Hans knew the direction from studying the camp perimeter during work details. Friedrich had memorized the road layout from a map in the camp library.

Kurt just followed, half terrified, half exhilarated. The desert at night was cold. Stars burned overhead in impossible numbers. Jack rabbits bolted from their path. Once they froze as headlights swept past on a distant highway, but no one stopped. No one saw three skinny boys in threadbear P uniforms moving through the darkness like ghosts.

They reached the outskirts of Scottsdale just after 8:00. The main street glowed like a carnival. Neon signs advertised restaurants and drugstores. The Valley Theater marquee blazed with lights announcing a double feature. Going my way starring Bing Crosby, followed by a western they didn’t recognize.

People strolled the sidewalks laughing and chatting. It was a vision from another world. The boys had no money. They had no plan beyond reaching the theater. But Fortune smiled on desperation. Behind the building, an exit door stood propped open with a brick, probably left by an usher taking a smoke break. Hans pushed it wider.

They slipped inside, hearts pounding, and found themselves in a dim corridor smelling of popcorn and candy. The theater was half full. They found seats in the back corner shrouded in shadow. As the lights dimmed and the projector worred to life, something extraordinary happened. The war disappeared. The camp vanished. For the first time in over a year, they weren’t prisoners or soldiers or enemy combatants.

They were just three boys watching a movie. Bing Crosby sang on screen. The audience laughed at jokes the boys only half understood. But it didn’t matter. The music mattered. The warmth mattered. The normaly mattered. Kurt felt tears on his cheeks and didn’t wipe them away. Friedrich grinned like an idiot in the flickering darkness.

Hans closed his eyes during the musical numbers and just listened. The double feature ran nearly 3 hours. When the lights came up for intermission, the boys ducked low in their seats. An elderly usher passed their aisle, but didn’t look twice. When the second film started, a cowboy picture full of horses and gunfights. They relaxed slightly.

This was it. This was the madness they’d risked everything for, and it was worth it. But as the credits rolled and the audience stood to leave, reality crashed back. They had to return. Not because they feared punishment, though they did, but because they’d promised each other. This wasn’t an escape.

It was a 2-hour leave, a stolen moment of freedom that they’d chosen to bookend with captivity. They slipped out the same back door just before midnight. The street was quieter now. A few cars cruised past. A cop stood outside a diner sipping coffee. The boys kept to the shadows, moving east toward the desert.

No one stopped them. No one even noticed. The walk back felt longer. Cold settled into their bones. The adrenaline faded, replaced by exhaustion and creeping dread. What would happen now? Would they be shot trying to re-enter the camp? Sent to a harsher facility, court marshaled by their own German command in the camp? They approached Camp Papago Park from the east just after 1:00 in the morning.

Flood lights still blazed. Guards still patrolled the perimeter. But the siren had stopped. The dogs were quiet. Hans led them back to the same gap in the fence. They crawled through one by one and then they walked toward the main gate. No hiding, no sneaking. They simply walked up the road, hands visible, and stopped 50 yards from the guard post.

Friedrich called out in broken English. We are back. We are here. Sergeant Clayton nearly fell out of his chair. He grabbed his rifle and flashlight, shouting for backup. Two more guards rushed to the gate. Their lights swept over the three boys who stood in the road covered in dust, shivering, utterly unarmed. One of them had popcorn kernels on his shirt.

Clayton approached slowly, rifle raised, but finger off the trigger. Where the hell did you go? His voice was more baffled than angry. Hans tried to explain in his limited English. We go movie then come back. Clayton stared at him. You You went to the movies? Friedrich nodded vigorously. Yes, movies. Bing Crosby. Very good.

Before we continue further into this unbelievable story, hit that like button and subscribe to keep these hidden tales of World War II alive. Drop a comment below telling us where you’re watching from and share this with anyone who loves history’s most surprising moments. Now, let’s continue. The guards didn’t know whether to laugh or shoot. They radioed the command post.

Within minutes, Colonel Davies himself arrived, still buttoning his uniform jacket. He looked at the three boys, exhausted and shivering, then at Sergeant Clayton. They went where? Clayton cleared his throat. to the cinema, sir, in town. Then they came back. Davies ordered them confined to the Camp Brig pending investigation.

But as the guards led them away, the colonel stood in the desert darkness, staring at the lights of Scottsdale in the distance. Something about the absurdity of it struck him. These weren’t hardened enemies. They were children. Children so desperate for a taste of normaly, they’d risked execution for a movie. The next morning, the interrogation began.

Davies questioned each boy separately. Their stories matched perfectly because they were simply telling the truth. They hadn’t contacted anyone in town. Hadn’t attempted to acquire weapons or transportation. Hadn’t tried to send messages to Germany. They’d watched Bing Crosby sing, eaten popcorn found on the floor, then walked back.

The military command in Washington wanted harsh punishment. escaped prisoners, regardless of intent, represented a security failure. But Davies pushed back. He submitted a full report emphasizing the boy’s voluntary return and complete lack of hostile intent. He noted their age, their good behavior record, their cooperation during interrogation.

In the end, the punishment was solitary confinement for 2 weeks, followed by loss of work privileges for a month. Light, considering they’d technically escaped a prisoner of war camp. But the story didn’t end there. Word spread through Camp Papago Park like wildfire. The other prisoners heard about the movie theater escape. Some laughed.

Some called the boys fools. But many understood. Years later, Friedrich Becker gave an interview to a German documentary filmmaker. He was asked why they came back. Why not keep running? He smiled, an old man remembering his teenage self. We didn’t want to run. We wanted to remember what it felt like to be human, to sit in the dark and forget just for a moment that the world was on fire.

And then we wanted to go back because that’s where we belonged. Strange as it sounds, that camp was the safest place we knew. Hans Mueller never spoke publicly about the incident, but his daughter found a letter he’d written in 1945, never sent, addressed to Colonel Davies. In it, he thanked the colonel for understanding, for seeing them as boys, not just prisoners.

He wrote about sitting in that theater, listening to music, and feeling something he’d thought was lost forever. Hope, not hope for victory or escape. Hope that somewhere, somehow, people were still laughing and singing and living. Kurt Hoffman died in 1989 without children or much family. But his neighbor, a retired school teacher, remembered him telling the story once over beers.

He said it was the bravest and stupidest thing he ever did. But it reminded him why the war had to end, not for politics or territory, so kids could go to the movies on Saturday night without it being a crime. Camp Papago Park closed in 1945 after the war ended. The barracks were demolished, the fences torn down.

Today, a park and residential neighborhood occupy the land. A small historical marker notes the camp’s existence. It mentions the famous tunnel escape of 25 German officers in December 1944, a much larger and more dramatic breakout. But it says nothing about three boys who escaped for 2 hours just to watch Bing Crosby.

The story became a footnote, a curiosity, an odd anecdote in the vast machinery of World War II. But it represents something profound. Even in the machinery of total war, humanity persists. The desire for normaly, for beauty, for simple joy cannot be entirely crushed. Three boys prove that in the Arizona desert in 1944.

They didn’t defy an empire or change the course of history. They didn’t strike a blow for freedom or make a political statement. They just wanted to be kids again. For 2 hours in the dark, they weren’t German or American, soldier or prisoner, enemy or ally. They were just boys watching a hero save the day.

And then they walked back into captivity because even stolen moments must end. The war ended 7 months later. Hans, Friedrich, and Kurt were repatriated to Germany in late 1945. They returned to a shattered nation of rubble and grief. They rebuilt their lives in the ruins, carrying with them a secret that seemed too strange to share. A night in Arizona, when the barbed wire couldn’t hold them, not because they were desperate to flee, but because they were desperate to remember.

Sergeant Clayton retired in 1946. He kept a photograph on his desk until he died, a picture of Camp Papago Park under moonlight. His grandson asked about it once. Clayton told him the story of the three boys. They taught me something. He said, “You can lock people up. You can take away their freedom, but you can’t kill the part of them that just wants to feel normal.

And maybe that’s the part worth protecting most.” Colonel Davies went on to command several other P facilities. He never forgot the night he stood outside the gate staring at three exhausted boys who’d risked everything for a movie. In his memoirs published in 1968, he wrote a single paragraph about them. They reminded me that we weren’t guarding monsters.

We were guarding children forced to be soldiers. And children will always find a way to be children, even if just for a stolen moment. The Valley Theater in Scottsdale still stands, though under a different name. It shows independent films and hosts community events. The back exit, where three boys slipped inside in 1944, was sealed decades ago.

But on quiet nights, the current owner swears he sometimes hears laughter from the back rows when the theater is empty. Probably just old pipes or settling foundations. Probably. History remembers the great escapes, the tunnels and disguises, and desperate flights to freedom. But it often forgets the small rebellions, the quiet acts of humanity that defied the machinery of war in gentler ways.

Three boys didn’t dig for months or forge documents or fight their way to the border. They just walked through the desert to watch a movie. Then they walked back. That’s the story no one talks about. Not because it lacks drama, but because it reveals something uncomfortable. Even enemies are human. Even prisoners deserve beauty.

Even in the darkest moments, people hunger for light. And sometimes the bravest thing you can do is choose to come back. To face consequences for a stolen piece of normaly to prove that not everything the war touched was destroyed. November 12th, 1944. Camp Papago Park, Arizona. Three boys vanished into the desert night. But they didn’t escape.

They just went to the movies. And in doing so, they proved something the war tried desperately to erase. That hope, joy, and the simple desire to be young could survive even behind barbed wire. For 2 hours, they weren’t prisoners of war. They were just boys in the back row eating popcorn, watching the hero save the day.

Then they chose to return to captivity because they understood something profound. Freedom isn’t just about breaking out. Sometimes it’s about remembering what you’re hoping to return to when the war finally ends.