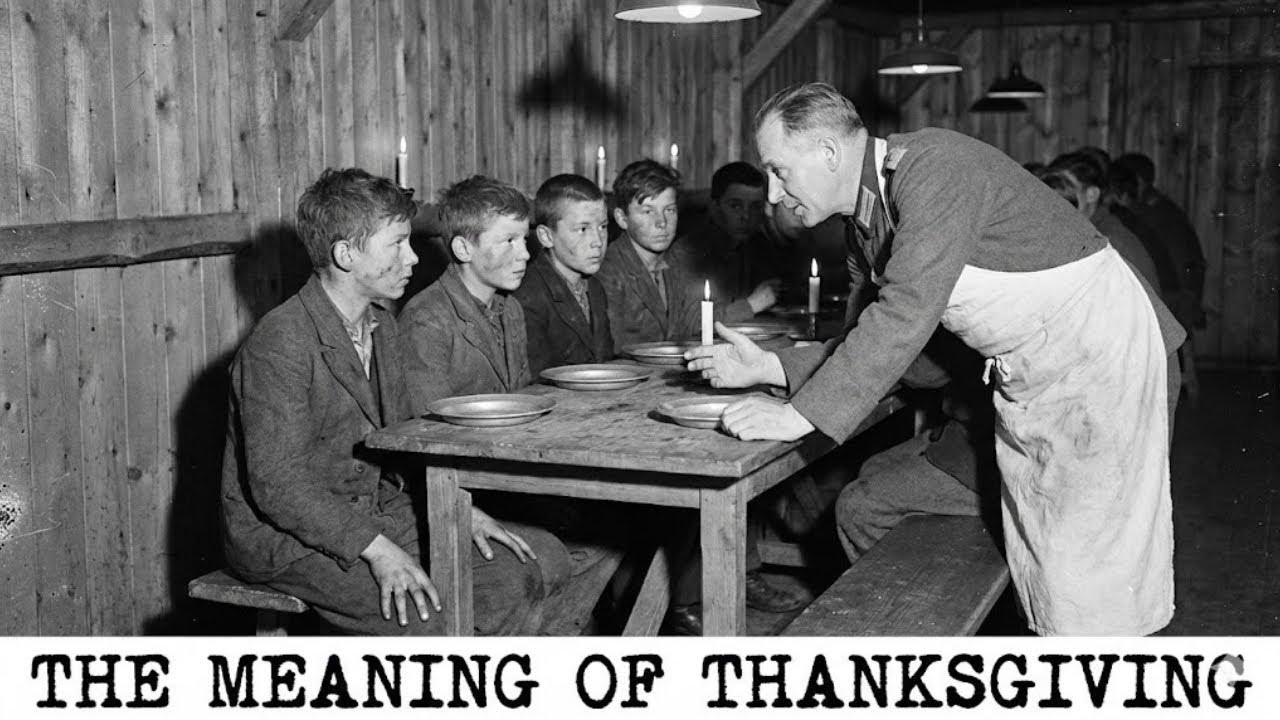

November 23rd, 1944. Campbell, Kentucky. The mess hall doors swung open to the smell of roasted turkey. Steam curled from metal trays piled with mashed potatoes and cranberry sauce. At the corner table, 12 boys in greywool shirts sat with their arms crossed. Their plates sat empty. Their eyes stayed fixed on the floor.

The boys ranged from 14 to 17 years old. Their faces were gaunt, their wrists were thin. They had been German soldiers 3 weeks earlier. Now they were prisoners of war on American soil, and they had just been offered a feast they refused to touch. The other PS in the camp, older men, vermarked veterans, had taken their portions without question.

But these boys were different. They had been raised in a different Germany. They had been taught different lessons, and on this Thursday morning they sat in silent rebellion, convinced the meal before them was a trap. That moment, when hunger met suspicion, when gratitude collided with ideology, would become a turning point none of them expected.

Because what happened next wasn’t a punishment. It wasn’t a lecture. It was a story. And that story would crack open something the war had sealed shut. The boys had arrived at Camp Campbell in early November. They were part of a transport from the European theater. Most had been captured in France or Belgium during the Allied push eastward.

Their uniforms had been replaced with plain workclo. Their weapons had been taken, but their convictions remained intact. They were Hitler youth veterans. Not all of them had volunteered, but all of them had been shaped by the same machine. From the age of 10, they had attended rallies. They had sung songs about sacrifice and strength.

They had been told that Germany was destined to rule. And they had been warned that surrender was the ultimate betrayal. In the barracks at Camp Campbell, they kept to themselves. They didn’t fraternize with the older prisoners. They didn’t speak to the guards unless ordered. At night, they whispered in German about escape routes and honor.

During the day, they worked in silence, hauling supplies and clearing brush. They moved like ghosts through a world they no longer understood. The camp itself was massive. It sprawled across more than a 100,000 acres of rolling Kentucky farmland. It had been built in 1942 to train armored divisions.

By 1944, it also housed thousands of German and Italian PS. The prisoners worked on farms, in factories, and in camp kitchens. They were treated according to the Geneva Conventions. They were fed. They were housed. They were paid a small wage. But the boys didn’t see it as mercy. They saw it as confusion.

In their world, enemies were meant to destroy each other. Captured soldiers were meant to suffer. The kindness they encountered felt like weakness. and weakness they had been taught was something to exploit. On the morning of November 23rd, the camp commander had issued a special order. It was Thanksgiving. The prisoners would receive the same meal as the American soldiers.

Turkey, stuffing, gravy, pumpkin pie. It was a gesture meant to show humanity. It was also a test. The older prisoners understood. They had lived through the first war. They had known hunger. They had learned that survival sometimes meant swallowing pride along with bread. But the boys had no such wisdom. To them, the feast looked like propaganda.

It looked like a celebration of American dominance. It looked like surrender dressed up as charity. So when the trays were set before them, they refused. They sat with their hands in their laps. They stared at the food as if it were poisoned. and the messaul filled with the clatter of forks and the hum of conversation grew quiet around them.

Before we continue, if you’re finding this story as powerful as we intended, hit that subscribe button and let us know in the comments where you’re watching from. Your support keeps these forgotten stories alive. And if you believe history should never be forgotten, share this video with someone who needs to hear it.

Now, back to that cold November morning in Kentucky. The camp cook noticed first. His name was Robert Dunn. He was 52 years old. He had served in the First War as a supply sergeant. He had come home to Kentucky and opened a diner in Clarksville. When the Second War began, he had volunteered again, not to fight, to feed.

Dun had cooked for soldiers, prisoners, and refugees. He had seen men eat in silence after losing their units. He had watched boys cry into their soup. He understood that food was more than fuel. It was memory. It was home. And for some, it was the only kindness they could accept. He stood at the kitchen window and watched the 12 boys.

He saw the defiance in their posture. He saw the fear beneath it. He had seen that look before. It was the look of children who had been trained to believe that mercy was a lie. Dun wiped his hands on his apron. He stepped out from behind the serving line. The messaul grew quieter still. The otherprisoners watched. The guards watched.

The boys watched. Dunn walked slowly to their table. He didn’t carry a tray. He didn’t carry a weapon. He carried only his age and his accent. A soft Kentucky draw that sounded nothing like a drill sergeant. He pulled up a chair. He sat down. He didn’t speak immediately. He let the silence stretch.

Then he asked in broken but careful German if they understood English. One of the boys, a tall, thin 17-year-old named Klouse, nodded. Dunn switched to English. He spoke slowly. He told them he wasn’t there to punish them. He wasn’t there to argue. He was there to tell them a story. And if they wanted to leave their plates empty after hearing it, that was their choice. The boys glanced at each other.

Klaus translated quietly. Then they turned back to Dun and he began. He told them about a group of people who had crossed an ocean. Not as conquerors, not as soldiers, but as refugees. They had been fleeing persecution. They had been starving. And when they arrived in a new land, they had no idea how to survive.

He told them about the first winter, how half of them had died, how the rest had huddled in makeshift shelters, burning whatever they could find, how they had eaten their seed corn, how they had buried their children in frozen ground. He told them about the strangers who had saved them, not out of duty, not out of politics, but because they saw suffering and chose to act.

Those strangers had taught the refugees how to plant, how to fish, how to survive the seasons. They had shared their food when they had little to spare. And when the harvest came, the refugees had held a feast. Not to celebrate victory, not to mark conquest, but to give thanks, to acknowledge that they had been saved by people they had once feared, to recognize that survival was a gift. Dun leaned forward.

He looked at Klouse. Then at the other boys, he told them that Thanksgiving wasn’t about America beating Germany. It wasn’t about soldiers or flags. It was about strangers feeding strangers. It was about survival. He stood up. He said nothing more. He walked back to the kitchen. The messaul remained silent. The boys sat frozen.

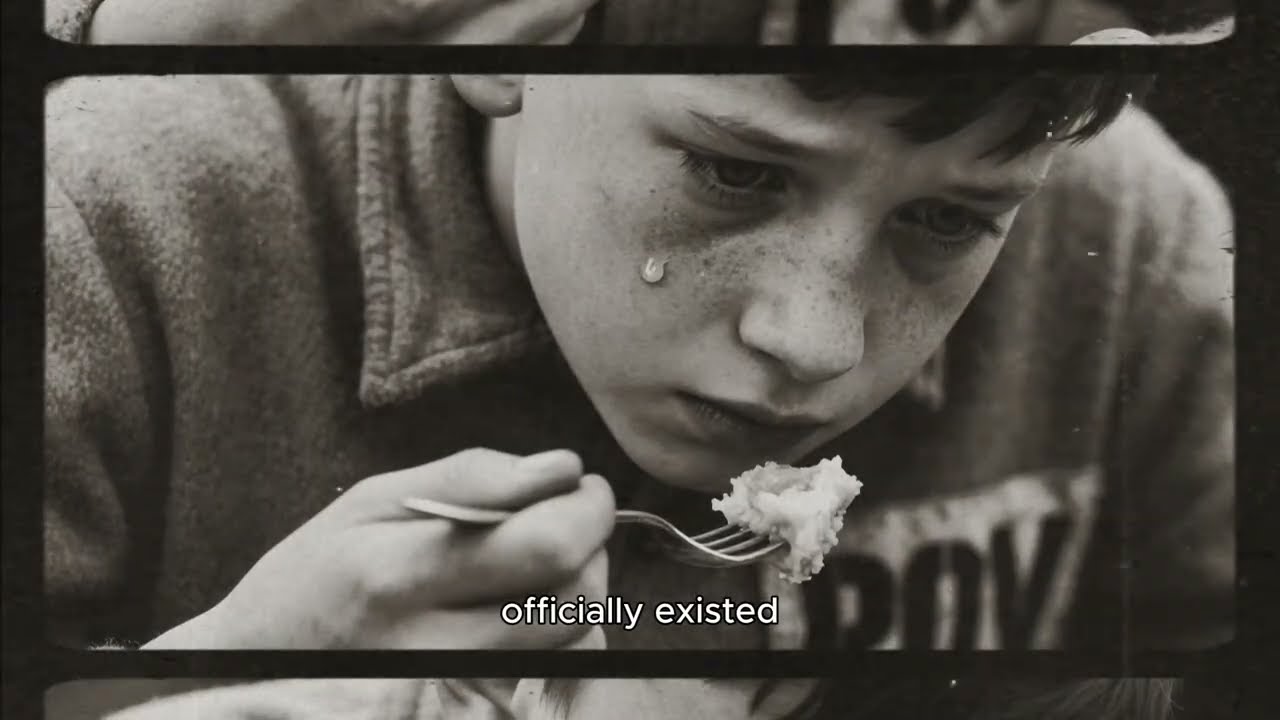

Then Claus picked up his fork. He didn’t eat right away. He stared at the turkey. He stared at the cranberry sauce. Then he spoke quietly in German. He said they weren’t eating because they were Americans. They were eating because they were still alive. And being alive meant something.

One by one, the other boys reached for their forks. They didn’t speak. They didn’t smile. But they ate slowly, carefully. As if each bite required permission, they were only now granting themselves. The guards didn’t cheer. The other prisoners didn’t applaud. But something shifted in the room. The tension that had coiled around the table loosened.

The act of eating, of accepting the meal, became something more than obedience. It became acknowledgment. For the boys, it was the first crack in the armor they had worn since childhood. They had been taught that the world was divided into the strong and the weak, the victors and the defeated, the righteous and the damned. But Robert Dunn’s story had introduced a third category, the saved.

They had thought they were defeated soldiers. Now they realized they were refugees. They had fled a burning country. They had survived battles they hadn’t chosen. And now they were being fed by strangers in a land they didn’t understand. Just like the pilgrims, just like the people in Dun’s story.

Klouse finished his plate first. He set down his fork. He looked at the other boys. One of them, a 14-year-old named Verer, was crying. Not loudly, just silent tears that ran into his mashed potatoes. No one said anything. They just kept eating. After the meal, the boys returned to their barracks. They didn’t talk about what had happened. Not that night.

But over the following weeks, something changed. They began to speak to the older prisoners. They began to ask questions, not about the war, about the world before it. They asked about farms, about families, about what it had been like to live without fear. The older men answered carefully. They didn’t lecture. They didn’t judge.

They just told the truth. And slowly the boys began to remember that they had once been children. Robert Dunn never spoke about that day. He didn’t write it down. He didn’t seek recognition. He simply returned to the kitchen and kept cooking. But the story spread. The guards told other guards. The prisoners told other prisoners.

And years later, when some of those boys returned to Germany, they told their own children. One of them, Klouse, would write a letter in 1953. It was addressed to Camp Campbell. It was forwarded to Dun’s Diner in Clarksville. In it, Klouse explained that he had spent years trying to forget the war. But he couldn’t forget the cook.

He couldn’t forget the story, and he wanted Dunn to know that the meal had saved more than his body. It had saved something deeper. Dunnnever replied, but he kept the letter. It was found after his death in 1967, tucked inside a Bible on his kitchen shelf. The other boys scattered. Some returned to shattered cities. Some immigrated to South America.

Some stayed in the United States. But they all carried the same memory. They all remembered the moment they stopped being soldiers and became survivors. Thanksgiving 1944 at Camp Campbell wasn’t a grand moment. There were no cameras, no speeches, no medals. It was just a cook and 12 boys in a messaul. But it became a reminder that the smallest acts of humanity can shift the trajectory of a life.

The boys had been taught that surrender was weakness, that mercy was manipulation, that enemies could never be anything but enemies. But Robert Dunn had shown them something else. He had shown them that history is full of people who were saved by strangers. And that being saved doesn’t make you weak. It makes you human.

The war would continue for another 6 months. Millions more would die. Cities would burn. Borders would be redrawn. But in a messaul in Kentucky, 12 boys learned that gratitude isn’t about politics. It’s about recognizing that survival is a shared experience. And that sometimes the people who feed you are the ones who teach you how to live.

When the plates were cleared that morning, the boys didn’t thank Dunn. They didn’t salute. They simply stood and walked back into the cold November air. But they walked differently. They walked like people who had just remembered they were allowed to be hungry, allowed to be fed, allowed to be grateful. And in that moment, they understood what Dunn had been trying to say.

Thanksgiving wasn’t a victory feast. It was a survivor’s meal. And they were survivors now. Not because they had fought, but because they had chosen to eat. Years later, one of the boys would say it best. He would tell his grandson about that day, about the cook, about the turkey and the story.

And when the grandson asked what it meant, the old man would answer simply. He would say they thought they were prisoners, but they were pilgrims. That was how Robert Dunn always framed it later. Not with speeches or sermons, not with flags or slogans, but with that one quiet comparison that made people stop and think.

Pilgrims were not conquerors. They were not heroes in parades. They were people who crossed oceans because they had no better choice. People who survived storms because turning back was impossible. people who arrived in strange places carrying nothing but hunger, fear, and the fragile hope that someone somewhere would open a door.

These boys had crossed an ocean, too, though not by choice. They had survived a storm of steel and fire instead of wind and water, and they had been saved by strangers in a strange land. Men who wore the uniform of their enemy, and spoke a language they barely understood, just like the people in the old story. Just like everyone who has ever had to learn what it really means to say thank you. When pride is useless.

When history is loud. When gratitude is the only thing left that makes sense. The messaul is gone now. The long wooden tables where they sat shoulderto-shoulder no longer exist. Campbell became Fort Campbell. And then something larger, more modern, more permanent. The barracks were torn down, replaced by new buildings with clean lines and fresh paint.

The fields where guards once stood watch grew quiet, then busy again with different soldiers, different wars, different generations of young men who had never heard the names of those 12 boys. The prisoners returned home, some to cities reduced to rubble, some to villages that barely remembered them, some to families that had aged years and months.

They carried the weight of defeat, of survival, of questions they would spend the rest of their lives trying to answer. But the story stayed behind. It settled into the cracks of memory and waited. It remains because it wasn’t really about war in the way wars are usually told with maps and arrows and casualty lists.

It was about what happens when war pauses long enough for people to look at each other without aiming. When the guns fall silent, even for a moment. When orders give way to instincts older than uniforms, and when the only question left is whether you can accept the hand that feeds you, even if that hand belongs to someone you were taught to hate.

And for 12 boys in November of 1944, the answer was yes. Not because they stopped being German or suddenly became American. And not because the world had been fixed or the fighting had ended or the future was suddenly clear. It was because they realized they were something older than both. They were human. They were hungry.

And they were grateful. Grateful for warm food after months of cold, for a chair instead of frozen ground. For a moment when no one was shouting, when no one was running. When no one was counting shells or casualties or miles to the next front, they were gratefulfor hands that served instead of struck, for faces that looked at them not as targets, but as boys who needed to eat.

That was the lesson Robert Dunn taught without ever raising his voice. He didn’t call it diplomacy or strategy. He didn’t write it in a manual or carve it into stone. He simply ladled food onto plates, told his men to make room at the table, and treated enemies like guests for one night.

In doing so, he showed them what peace looked like before peace officially existed. That was the tradition he passed down without ever knowing it would be remembered. No medals were pinned to his chest for it. No headlines ran. No generals rewrote plans because of that meal. It happened quietly, the way the most important things often do, unnoticed by the world, unforgettable to the people sitting there.

And that was the moment when Thanksgiving stopped being a holiday and became a truth. A truth that survived the war, survived the years, and still echoes in the quiet corners of history. Where the smallest gestures matter most, where kindness leaves deeper marks than bullets, and where a shared table can do what armies cannot.

The truth that sometimes the most powerful weapon isn’t a gun, but a meal. And that the most powerful victory isn’t conquest, but the choice to sit down and eat with the enemy, to pass the bread, pour the coffee, and meet another person’s eyes long enough to see fear reflected there, too.

That’s what those boys learned in that messole so many years ago. And that’s what we remember. Not because it changed the course of the war or shifted a border or altered a treaty, but because it changed them. And in changing them, it reminded us all of what we’re really fighting for when the battles finally end. Not territory, not pride, not vengeance, but the simple, quiet miracle of being alive, of being fed, of being grateful, of being human again.