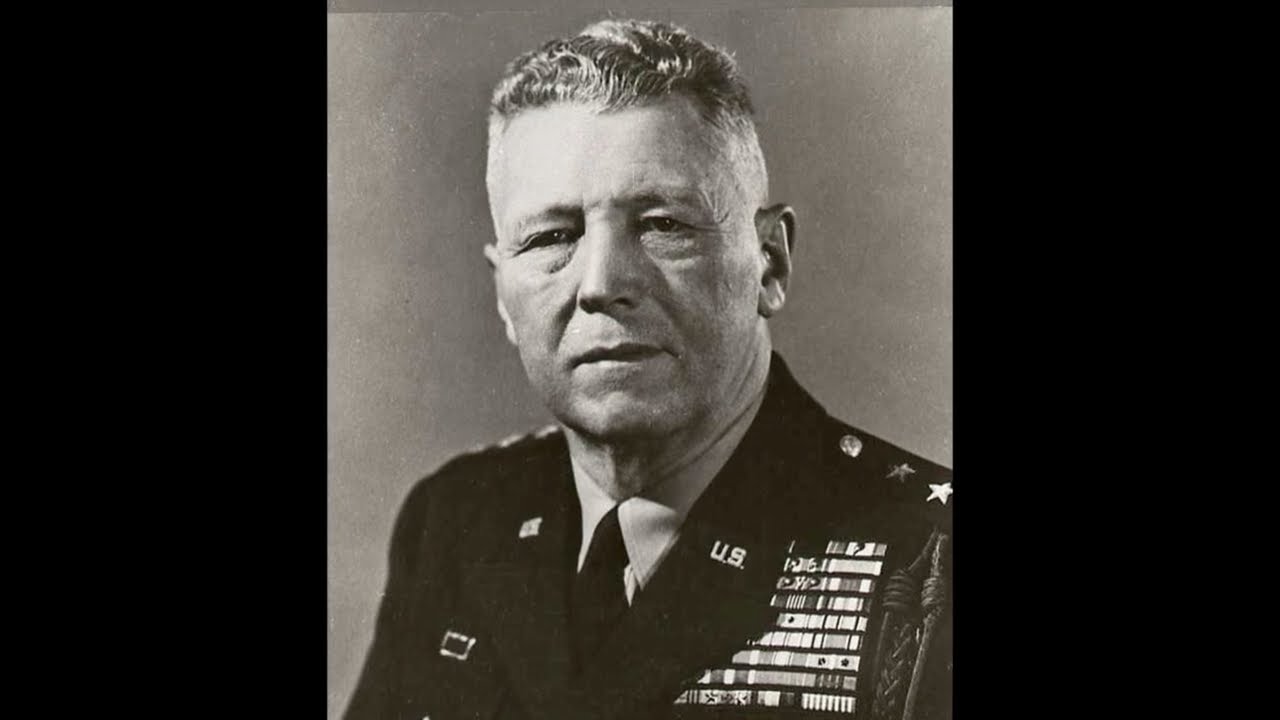

September 18th, 1944. General Hassan Montufil stood in his command post near the German border, studying a map that for the first time in months promised something he had almost forgotten, victory. Montufil was 51 years old. He was not a fanatic. He was a pragmatist, a master of armored warfare who had fought in Russia and North Africa.

He had seen armies collapse. He knew the Vermacht was bleeding to death on two fronts. But on this morning, he believed he held a winning hand. Under his command was the 113th Panzer Brigade. This was not the battered remnants of Normandy divisions held together by prayers. This was Hitler’s new fire brigade.

Fresh formations sent directly from the factories. The tanks were so new that some crews were still learning their turret mechanisms. The brigade was equipped with 58 brand new Panther tanks, the deadliest tanks on the Western Front. Mantiful did the math with cold precision. The American Sherman tank was a reliable workhorse, but it was a medium tank with a generic 75 mm gun.

Its frontal armor could be penetrated by a Panther from 2,000 m away. The Panther’s sloped armor could bounce American shells like pingpong balls. The Panther’s 75 mm gun could kill a Sherman from distances where the American gun was merely ineffective. He studied the fuel calculations. The 113th Brigade had been allocated 600,000 L of fuel, enough for 2 days of intensive operations.

2 days, that was all he needed. His objective was elegant. Slice into the exposed right flank of General George Patton’s third army. Patton was overextended, his fuel lines stretched across 400 km, his tanks scattered across 180 km of front. Manufel’s plan was to concentrate his 58 Panthers and punch directly at the American Fourth Armored Division, cut off Patton’s spearheads, destroy them in detail, create a crisis that would force the Americans to halt their entire advance.

By all conventional military logic, this should have worked. The German tanks were superior. The German numbers were concentrated. The element of surprise was absolute. The Americans had no idea a fresh pancer brigade was assembling in the fog and forests of Lraine. But Monttofeld was making a calculation based on 1940s logic in a 1944 reality.

He assumed a tank battle was decided by armor thickness and gun caliber. He did not know he was leading his brigade into a trap constructed from three things the German military mind could not comprehend. At 7:30 hours on September 19th, the lead elements of the 113th Panzer Brigade began their approach march toward their assembly areas.

A thick, heavy fog rolled across the lraine fields like a living thing. Visibility dropped to 50 yards, then 30 yards. Tank commanders peered through periscopes. Drivers could barely see the tank in front of them. Mantel’s greatest advantage, the longrange killing power of the Panther’s 75 mm cannon instantly evaporated.

A 2,000 m kill shot requires sight. These panthers couldn’t see 50 m. The fire brigade was blind. Inside the American Combat Command, a headquarters 15 km away. Colonel Bruce Clark received the first reports from forward observers. Heavy engine noise, large formations. Moving west. Clark didn’t have heavy tanks. He had the 37th Tank Battalion commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Kraton Abrams, a name that would one day adorn America’s main battle tank. Abrams didn’t panic.

He realized instantly that the fog was an equalizer, a catastrophic one. If the Germans couldn’t see at 2,000 yards, their superior guns were useless. This was going to be a knife fight in a phone booth. Speed and reaction time were everything. The German column advanced through the mist, tank engines roaring, tracks clanking, commanders hunched in their cupillas.

They expected to crush the American picket line and break into the rear. Instead, the lead Panther suddenly erupted in flames. The turret exploded outward, then the second Panther in column, then the third. The German crews panicked. Radio discipline collapsed. Tank commanders sued their turrets left and right, desperately searching for muzzle flashes in the fog, but there were none visible.

The shots were hitting them from the flanks, punching through the thinner side armor. Rounds that couldn’t penetrate the thick glacis plate were tearing through the weaker sides. German voices crackled over the radio in confusion. Enemy to the left. No, enemy right. Where is the enemy? commanders popped their hatches to see through the mist, only to be cut down by unseen machine gun fire.

The German commanders assumed they had run into a massive wall of American heavy tanks. But the reality was far more disturbing. The 113th Panzer Brigade hadn’t hit a wall. They had walked into a swarm. Enter the M18 Hellcat tank destroyer. To a German tanker, the Hellcat was almost a joke. It had almost no armor.

A heavy machine gun could penetrate its thin turret. It had an open top, leaving the crew exposed to shrapnel and grenades. By Vermach standards, which valued protection above all else, it was a suicide machine. But the M18 had one statistic that Montell had completely ignored in his calculations, powertoweight ratio. The Hellcat weighed only 17 tons.

Despite that minimal weight, it was powered by a radial aircraft engine, the same type that powered American fighter planes. This engine was a technological marvel, producing 350 horsepower. It could achieve road speeds of 55 mph, faster than any tank in the world. No Panther, no Tiger, no Soviet T34 could match that speed.

The Hellcat could relocate from one position to another faster than a medium tank could rotate its turret. In the fog of Aracort, this speed became the ultimate weapon. The German Panthers advanced in a rigid falank like Roman legionaries in formation. They were designed to advance in coordinated groups, supporting each other’s flanks, but coordinated tactics require visibility and communication.

The fog destroyed both. The American Hellcats fought like a pack of wolves, individual hunters, autonomous, coordinated not by proximity, but by radio. Here is how the engagement unfolded, repeated dozens of times that morning. A Hellcat platoon from the 704th Tank Destroyer Battalion would hear the Panthers approaching through the fog.

The commander listening on the radio would plot his position on the map. He would order his driver to race to a flank position hidden behind a hedger or barn. The engine would scream at full throttle. The crew would deploy into firing positions. They would wait. Engines idling. Gunner with hand on the firing mechanism.

Loader with armor-piercing rounds staged for rapid reload. They would wait until the German behemoths rolled past exposing their vulnerable sides. Three high velocity 76 mm rounds would slam into the side of a Panther. Penetration fire. The Panther’s turret would slew left trying to engage the Hellcat, but the Hellcat was already moving.

The driver would reverse at full throttle. The vehicle would back up 300 yd at near maximum speed, guided by the commander shouting directions. They would relocate 300 yd down a different road across different terrain toward the next ambush position. Before the surviving German tanks could complete their turret rotation, the Hellcats had vanished.

It was a clash of philosophies. The Germans built tanks as armored fortresses, heavy, protected, designed to take a hit and survive. The Americans built vehicles to never be there when the hit arrived. Light, mobile, designed to shoot and relocate. By noon, the fog began to lift. Manufil, receiving reports of stalled attacks and mounting losses, ordered his commanders to push harder.

The Americans cannot be everywhere, pushed through their screen. But as the sun burned off the mist, the Germans realized the second part of the American trap had just closed. During the opening hours, the German infantry, the Panzer Grenaders, had ridden on the backs of the tanks or followed closely in halftracks to protect the armor from American infantry.

Suddenly, as the fog lifted, the sky above Araort tore open. It wasn’t airplanes. Not yet. It was something far more precise than anything the German mind could fathom. The American artillery, specifically the 66th Armored Field Artillery Battalion under Colonel Bruce Clark’s direct command, was executing a tactic that was standard doctrine for the fourth armored division, but a weapon of shocking lethality, time on target.

In traditional 1940s warfare, artillery batteries fired sequentially. Battery A would fire. The enemy would hear the first shell approaching. They would react. They would dive into foxholes. Battery B would fire 10 seconds later, but by then the enemy was already underground. The surprise was lost. The killing potential dropped by 90% after the first salvo.

The American time on target system was revolutionary. It was pure mathematics. A centralized fire direction center would calculate the flight time of artillery shells from 12 different batteries positioned miles apart at different elevations at different distances from the target. The FDC would then calculate backward from a specific impact time what firing time each battery required.

Battery A positioned 12 km away would fire at 1200 hours. Battery B positioned 4 km away would fire at 12:05. Battery C positioned 8 km away would fire at 12:010. The mathematics was precise. The ballistic tables were accurate. Every gun fired at a different moment, but every single shell arrived at the target coordinates at the exact same instant.

When the fog lifted on September 19th, Piper Cub spotter planes, tiny observation aircraft that looked like overgrown insects, circled overhead above the 113th Brigade positions. The pilots could see the German tank columns below. They called down coordinates. They became the eyes of the American artillery system for the 113th Panzer Brigade.

There was no warning, no ranging shots. One second, the Panzer Grenaders were advancing across a muddy field. The next second, the air above them simply disintegrated. Dozens of air burst shells detonated simultaneously at 30 ft altitude. The effect was apocalyptic. Shrapnel fell like razor-sharp rain. The blast waves were lethal.

The Panza Grenaders, elite infantry riding on the tanks, were decimated. Dozens died in the initial salvo. Dozens more were wounded. The shrapnel didn’t scratch the Panthers armor, but it stripped the Panthers of something far more valuable. Their eyes and ears. The external radios were destroyed. Radio antennas mangled, telephone lines severed, command and control disintegrated.

Instantly, the German tanks were stripped of their defensive perimeter. They were buttoned up, hatches closed, commanders blind, isolated in explosions. A blind tank without infantry support is a dead tank. Without infantry to protect them from bazooka teams, the Panthers were helpless. Without commanders looking out, they couldn’t see the Hellcats flanking them.

Without radio contact, they had no situational awareness. Manufel’s elite brigade wasn’t engaged in a battle. It was being processed by a machine. By the afternoon of September 19th, the battlefield was littered with burning panthers. But the most shocking statistic wasn’t the tanks destroyed by fire.

It was the tanks that simply stopped. The 111th Panzer Brigade, supposed to support the 113th Brigade’s attack, arrived late. Why? Because they ran out of fuel on the way to the battle. Germany had designed the most sophisticated tank in history. Precision optics superior to anything the Americans possessed. Interleved road wheels, superior sloped armor, high velocity cannon.

But they couldn’t produce the liquid fuel to move 58 of these machines 20 km. Meanwhile, General Patton was screaming about fuel shortages. The Red Ball Express supply line, a continuous conveyor belt of trucks, was stretched thin. American tank units were rationing fuel. But here is the fundamental difference between American and German shortages.

When Americans lacked fuel, tanks turned off their engines and waited for trucks. When trucks arrived, tanks refueled and resumed operations within hours. When Germans lacked fuel, the tank was abandoned. Crews dynamited the gun breach to prevent capture. They disabled the engine. They set demolition charges. The tank was left to rust in the mud.

As the battle raged over 3 days, the disparity became almost comical. American recovery crews towed damaged Shermans back to mobile repair depots during the battle. Tank mechanics working in outdoor workshops in combat zones were welding patches over shell holes. They replaced damaged engines. They straightened bent gun barrels.

Tanks knocked out in the morning would refuel, recrew, and returned to the line by evening. The Germans had no recovery vehicles. If a Panther threw a track, it was abandoned. If transmission failed, abandoned. If the engine caught fire, the crew bailed and the tank burned. There was no replacement pipeline, no spare engines from factories.

The 113th Panzer Brigade entered the battle with 58 Panthers. Within 24 hours, they had lost 30. Within 48 hours, 50. By the end of the week, only eight remained operational. The US Fourth Armored Division lost tanks to combat command. A lost five Sherman tanks and three tank destroyers in the first crucial day. Total losses for the week were approximately 25 tanks and tank destroyers.

But critically, American losses were rapidly replaced. Within 3 days, new Shermans arrived from the rear. Within a week, Combat Command A’s operational strength was arguably higher than when battle started. Patton wasn’t defeating Mantel with tactics alone. He was defeating him with a supply chain extending across the Atlantic, back through English ports, back through American factories in Michigan, New Jersey, Ohio, back to the ore mines of Pennsylvania, back to the oil refineries of Texas.

Mantofl had built a perfect hammer, but the forge that created hammers was 3,000 mi away, rationed by Hitler’s government. On September 22nd, Mantofl issued orders for the 113th Panzer Brigade to disengage and retreat. The great counterattack had failed. The final accounting was brutal. The 113th Panzer Brigade entered the battle with 58 brand new Panther tanks.

By the end of the week, German records documented only eight still operational. The unit had effectively ceased to exist as a fighting force. In contrast, American Combat Command A reported total losses of approximately 25 tanks and tank destroyers. Losses that were replaced within days. The kill ratio was not a battle. It was an execution.

Araort proved that a superior weapon like the Panther is rendered absolutely useless if it is blind, unsupported by infantry, unable to move due to fuel shortage, and outmaneuvered by swarms of lighter vehicles operating with superior coordination and logistics. The Germans built warrior knights in shining armor. The Americans built a factory that moved at 50 mph, a factory with radios, a factory with supply trucks, a factory with spare engines and ammunition and fuel.

And in September 1944, in the fog of Lraine, the factory won. General Montel survived the war. He wrote memoirs about Lraine. He admitted that American time on target artillery and the mobility of tank destroyers made traditional panzer tactics obsolete. The battle of Arakort is often forgotten. It sits in the shadow of D-Day and the Battle of the Bulge.

It doesn’t have the dramatic scope of those operations. But it is perhaps the most important battle for understanding why Germany lost. Not because it was massive, but because it reveals the truth beneath the surface. It wasn’t just courage. Both sides had courage. German soldiers were not less brave than American soldiers.

It was the triumph of a system, a logistical system, a communication system, an industrial system, a system where speed, mobility, replaceable vehicles, and spare parts mattered more than individual warrior excellence. Thanks for watching Tales of Valor. If you enjoyed this deep dive into the mechanics of victory, how speed and logistics defeated superior armor, please like and subscribe for more forgotten World War II stories.

Tell us in the comments, would you rather command a panther with no gas or a Hellcat with no armor? Where are you watching from today? What other World War II stories should we cover next? Your engagement helps us continue bringing these untold narratives to light. Subscribe for more forgotten stories of World War II and the real lessons of industrial warfare.

We explore history through the lens of those who lived it. German commanders discovering why courage could not defeat systems. Japanese officers realizing that tactical excellence meant nothing against industrial supremacy. American soldiers understanding that wars are won in factories, not on battlefields.

Keep the history alive. We’ll see you in the next