December 11th, 1944. The Eagle’s Nest. Field Marshal Ger Fon Runstead stood against a concrete wall with his hands raised. Beside him stood Field Marshal Walter Model and General Hasso Mantoyfeld. The three most powerful commanders in the German West were being humiliated by the SS.

forced to surrender their sidearms, patted down [clears throat] like common criminals, their briefcases torn open and searched. The air in the room was heavy with silent fury. These were men of the old Prussian aristocracy. They valued honor above breath itself. And here they [clears throat] were being pawed at by political thugs. Inside the bunker, a trembling Adolf Hitler revealed his master stroke.

Operation Watch on the Rine, the Battle of the Bulge. 200,000 German soldiers would smash through the Arden and capture the port of Antwerp. Hitler assured them victory was certain. The Americans, he said, were cowboys and playboys. They would panic at the first shot. They would break and run just like they had at Casarine Pass two years earlier.

Fon Mantofel said nothing, but he did not share his furer’s confidence. Fawn Mantofl had fought the Americans. He knew they were not cowboys who would break at the first shot. But there was something else the German high command had gotten wrong. Something that would only become clear decades later. For decades, we have been sold a specific story.

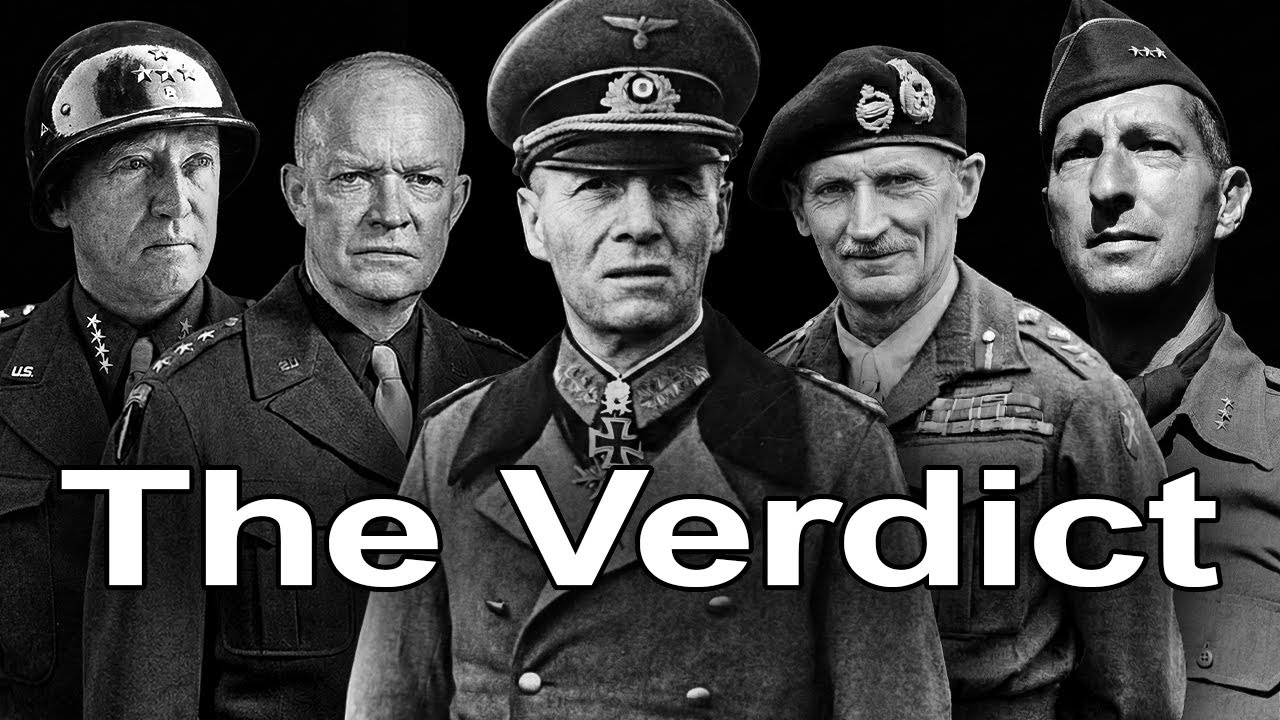

A story largely written by the German generals themselves. In their post-war memoirs and interviews, they claimed they had feared George Patton from the very start. They claimed they tracked his every move from North Africa to Normandy. They claimed he was the one man who kept them awake at night. It was a compelling story. It flattered the Americans and it saved the pride of the Germans.

But when historians finally cracked open the actual daily intelligence files from 1944, the documents written when the bullets were still flying, they found something shocking. The files were empty. In February 1944, 4 months before D-Day, German intelligence prepared detailed profiles on every senior Allied commander expected to lead the invasion.

Eisenhower, Montgomery, Bradley. Omar Bradley’s file was thorough. Montgomery’s was exhaustive. Patton’s file did not exist. There was no obsession. There was no fear. Until August 1944, there was barely a mention. The German generals had not been tracking Patton. They had been ignoring him. So, how did the man they ignored become the man they claimed to fear most? And if they were not watching Patton, who were they actually watching? The answers came from post-war interrogations conducted by American army historians and British

military writer BH Liddell Hart. For years, they interviewed captured German generals about their assessment of Allied commanders. What those generals revealed was far more complicated than the story they had been selling. Of all the Allied commanders, only one earned genuine contempt from German generals.

Mark Clark commanded the fifth army in Italy. He was tall, photogenic, and obsessed with his own image. He kept a personal public relations staff. He positioned photographers to capture his best angles. He believed he was destined for greatness. Field Marshal Albert Kessler commanded German forces in Italy. After the war, he offered his assessment of Clark with barely concealed disdain.

Kessler told interrogators that Clark was predictable because he was vain. Clark would always choose the option that generated the best headlines. Military logic was secondary to publicity. The proof came at Anzio in May 1944. Clark’s forces had broken out of the beach head. The German 10th Army was retreating north, exposed and vulnerable.

Clark had a chance to cut them off and destroy an entire German army. Instead, Clark turned his forces toward Rome. He wanted to be the liberator of the first Axis capital. He wanted the photographs, the headlines, the glory. He let the German 10th Army escape to fight another day. There is a tragic cost to that vanity. While Clark posed for photos in the coliseum, American infantrymen [clears throat] were still dying in the mud of northern Italy, fighting the very same German units Clark had failed to trap.

The photos were beautiful. The price was paid in blood. General Ziggfrieded Vestfall, Kessle Ring’s chief of staff, considered Clark one of the greatest assets German forces had in Italy. Not because of his skill, but because his vanity made him predictable. When you knew Clark wanted glory more than victory, you knew exactly what he would do.

If Clark was predictable because of vanity, Bernard Montgomery was predictable because of caution. Montgomery commanded the British 21st Army Group. He had defeated Raml at Elamagne. He was Britain’s greatest military hero. And German generals could set their watches by him. Runstad’s assessment was clinical. Montgomery was very systematic.

He said he would never attack until he had assembled overwhelming force. That approach worked if you had sufficient forces and sufficient time. But it also meant the Germans always knew when the attack was coming. General Gunther Blumenrit, chief of staff to run, demonstrated Montgomery’s methods during his interrogation. He stood up and walked across the room in slow deliberate steps, one foot carefully placed before the other.

No sudden movements, no risks. That Blumenred said was how Montgomery moved. They knew his formula. He required at least 2:1 superiority in men and 4:1 in tanks. They knew he would bombard for days before advancing. They knew he would stop at nightfall and consolidate rather than push through. This made him beatable.

Not through superior force, but through superior speed. If you could redeploy faster than Montgomery could prepare, you could always stay one step ahead. Operation Market Garden was the single time Montgomery abandoned caution. He gambled on a bold airborne assault to capture bridges across the Rine. It was audacious. It was aggressive.

It was everything Montgomery usually was not. It was also a catastrophic failure. 17,000 Allied casualties. The British First Airborne Division destroyed for the German defenders. It was a moment of grim satisfaction for the Allied paratroopers left isolated at Arnum. It was a nightmare. They had been dropped a bridge too far, sacrificed on the altar of a cautious general, trying to prove he could be bold.

German commanders noted the irony. The one time Montgomery tried to act like Patton, he proved why he should have stayed cautious. Not all British commanders earned German disdain. Harold Alexander commanded the 15th Army Group in Italy. Technically Montgomery superior in the Mediterranean. Where Montgomery was rigid, Alexander was flexible.

Where Montgomery demanded control, Alexander managed. Kesslering held Alexander in genuine respect. He called him a gentleman and meant it as the highest professional compliment. Alexander commanded what Kessler called a mongrel army. Americans, British, Canadians, free French, Poles, Indians, Brazilians, New Zealanders, dozens of nationalities with different equipment, different doctrines, different languages.

Holding them together required diplomacy that Montgomery never possessed. Kessler observed that Alexander understood coalition warfare. He did not demand that everyone fight his way. He found ways to use each force’s strengths while minimizing friction between allies. This made Alexander harder to predict than Montgomery.

He was not wedded to a single doctrine. [clears throat] He adapted to circumstances. He let his subordinate commanders exercise initiative. German generals saw Alexander as what Montgomery could have been if Montgomery had possessed any humility. a British commander who earned respect through flexibility rather than demanding it through arrogance.

The contrast was deliberate in German assessments. When interrogators asked about British leadership, German generals consistently praised Alexander while criticizing Montgomery. It was a rare thing in the brutality of the Second World War. A moment where enemy commanders looked across the battle lines and saw a reflection of their own professional code.

They wanted to kill Alexander’s army, but they would salute the man leading it. The message was clear. Germany’s enemies were not uniformly good or bad. Some Allied commanders earned genuine professional respect. Others did not. Dwight Eisenhower was supreme allied commander. He controlled more military power than any general in history.

German generals did not consider him a general at all. Runstat’s assessment was blunt. Eisenhower was a coordinator, not a commander. He was a political figure who managed the alliance. He was not a soldier who understood battle. German generals recognized that holding the Allied coalition together was genuinely difficult.

Americans and British had different strategic visions. Free French forces had political complications. Coordinating air, land, and naval operations across multiple theaters required organizational genius. Eisenhower had that genius. What he lacked in German eyes was killer instinct. Fawn manel told interrogators that Eisenhower’s insistence on the broad front strategy was wrong.

Instead of concentrating overwhelming force at a single point, Eisenhower advanced everywhere simultaneously. This prevented the Allies from achieving decisive breakthrough. Runstead agreed. He said the best allied course would have been to concentrate a powerful striking force and break through past Aken to the ruer.

Such a breakthrough would have torn the weak German front to pieces and ended the war in autumn 1944. Instead, Eisenhower spread his forces thin. He kept everyone advancing. He kept everyone happy, and he gave Germany six more months to fight. German generals saw this as proof that Eisenhower thought like a politician rather than a warrior.

He could not bring himself to favor one subordinate over another. He could not accept that military efficiency sometimes required political friction. The chairman kept the board together, but he never delivered the killing blow. Omar Bradley commanded the largest American force in Europe, 12th Army Group, over 1 million men.

[clears throat] German generals found him difficult to assess because he was difficult to see. Bradley did not seek publicity like Clark. He did not cultivate eccentricity like Patton. He did not demand attention like Montgomery. He simply commanded. Runstead called Bradley competent and methodical.

High praise from a Prussian field marshal, but not dramatic praise. Bradley was professional. Bradley was reliable. Bradley was exactly what you expected an American general to be. This made him dangerous in a different way than Patton. [clears throat] Bradley would not take insane risks. But he would not make mistakes either.

He would apply pressure steadily and relentlessly until something broke. German commanders noted that Bradley’s style reflected American industrial power. He did not need brilliance. He had overwhelming resources. His job was to apply those resources efficiently without catastrophic errors. Bradley did that job well.

The breakout at Sanlow, the race across France, the response to the bulge. Each operation was competent, professional, and successful. But German generals did not fear Bradley the way they feared others. They respected him as a professional. They did not lose sleep over him as a threat. Courtney Hodgeges commanded the First Army.

He fought more Germans than almost any other Allied commander. Most Germans could not remember his name. This was the paradox of American power. German generals spent years fighting the First Army. They bled against it at Normandy. They broke against it at Aen. They died against it in the Herkin forest. But when interrogators asked about Hajes specifically, German generals struggled to describe him.

They remembered the army, Fon Mantofl’s assessment was telling. He said the Americans fought like a machine, relentless, impersonal, unstoppable. Individual commanders mattered less than the system. First Army had unlimited ammunition. First Army had air superiority. First army had replacement troops and replacement tanks and replacement everything.

When one American unit was destroyed, another appeared to take its place. German generals had spent years studying individual commanders, looking for weaknesses to exploit. Against the American machine, individual weaknesses did not matter. [clears throat] You could not defeat a factory by killing its foremen.

This realization brought a specific kind of despair to the German front line. You can outsmart a man. You can trick a general. You cannot outsmart a tidal wave of steel. Facing the first army did not feel like a battle of wits. It felt like an execution by artillery. This terrified them more than any single general. Patton was dangerous.

Montgomery was predictable. But the American industrial machine was inevitable. Hajes was competent and unspectacular. But the machine did not require brilliance. It required management. German generals learned to fear what they could not name. And then there was Patton. German intelligence ignored him before D-Day.

They did not profile him. They did not track him. They assumed he had been sidelined after the slapping scandal. [snorts] They learned their mistake in August 1944. Patton’s third army broke out of Normandy and covered 400 m in 2 weeks. German commanders could not believe the reports. No army moved that fast.

Their maps were obsolete within hours of being drawn. Runstead’s assessment changed immediately. Patton was your best, he told American interrogators after the war. Not one of your best, your best. Yodel compared Patton to Gdderion, the father of German armored warfare. Patton was bold and preferred large movements.

He thought in terms of operational maneuver, not tactical grinding. Kessle Ring said Patton had developed tank warfare into an art. He compared him to Raml. Coming from the commander who had fought both men, this was the highest compliment possible. Berline, who had served under Raml in Africa, offered the most telling observation.

Other Allied commanders would let surrounded Germans escape. Patton would not. Byerline said he did not think Patton would let them get away so easily. What changed German perception was the battle of the bulge. German planners had calculated that American forces would need two weeks to respond to the Ardan offensive. Patton turned three divisions 90 degrees and began his attack in 48 hours.

Fon Mantofl received the reports and could not comprehend what he was reading. An entire army had moved 100 miles through winter storms in 2 days. Imagine the panic in the German command bunker. The map said they were safe. The math said they had time. And then through the snow and the fog came the roar of thousands of Sherman engines where silence should have been. It was not just a maneuver.

It was a shock to the system. After that, German generals stopped underestimating Patton. They had learned what happened when they assumed the gladiator was just another soldier. But Patton was not the only American who terrified German commanders. Lucian Trrescott never achieved Patton’s fame. He never commanded an army group.

He never made magazine covers or Hollywood movies. German generals in Italy feared him more than anyone except Patton himself. Trescot took command of Sixth Corps at Anzio in February 1944. The beach head had been stagnant for weeks under General John Lucas. German commanders had contained the landing and were grinding the Americans down.

Within days of Truscott taking over, Vestfall noticed the change. He reported to Kessler that American operations had suddenly stiffened. The same units that had been passive were now aggressive. The same positions that had been static were now probing. Nothing had changed except the commander. Trrescott believed in a marching standard known as the Truscott Trot.

His units trained to march faster than standard doctrine allowed. They attacked before defenders expected. They exploited gaps before the enemy could react. It was a pace that blistered feet and broke men. But Truscott drove them because [clears throat] he knew the grim math of war. Sweat saves blood. If you move faster than the enemy can think, you win. If you slow down, you die.

German commanders recognized this as genuine tactical excellence. Trescot was not famous because he did not seek fame, but he was dangerous because he understood mobile warfare the way Patton understood it. After the war, when German generals listed the Allied commanders who genuinely concerned them, Truscott’s name appeared alongside Patton.

Not Montgomery, not Bradley, not Clark. The professionals recognized a professional, and Truscott was the hidden blade the public never learned to fear. German generals ranked Allied commanders by a simple standard. Who kept them awake at night? Clark gave them opportunities. Montgomery gave them time. Eisenhower gave them six extra months of war.

Bradley and Hodes gave them a grinding death they could not escape. Alexander earned their respect. Trrescot earned their fear. Patton earned both. The rankings were not about who was the best person or the best leader. They were about who was the most dangerous enemy. By that measure, German generals were clear. speed killed, aggression killed, predictability saved their lives.

In the end, the German ranking of Allied commanders tells us less about the Americans and more about what the Germans had lost. They respected the oldw world professionalism of Truscott and Alexander because it reminded them of themselves, but they feared the machine of Hajes and the speed of Patton because it showed them the future.

And in that future there was no place for the vermocked.