In the blazing Texas sun of 1944, a cloud of dust drifted behind a convoy of olive drab army trucks. They rumbled through miles of open ranchland, the air thick with heat and the distant hum of cicadas. Inside the truck sat a group of German women, nurses, clerks, and auxiliaries of the Reich. Captured in North Africa and transported across an ocean to the most unlikely place imaginable, the American Southwest.

For most of them, it was their first glimpse of freedom. But they didn’t know it yet. They expected punishment, interrogation, chains. The stories they’d been told about American brutality were vivid and terrifying. Some whispered that Americans beat prisoners for sport, that they starve them or sent them to mines in the desert.

As the trucks rolled deeper into Texas, fear filled the silence. But then through the slats of the truck bed, one woman caught sight of something she never expected. A wide endless horizon. No walls, no ruins, just sky. And beneath it, a ranch hand on horseback. Hat pulled low, watching the convoy with calm curiosity.

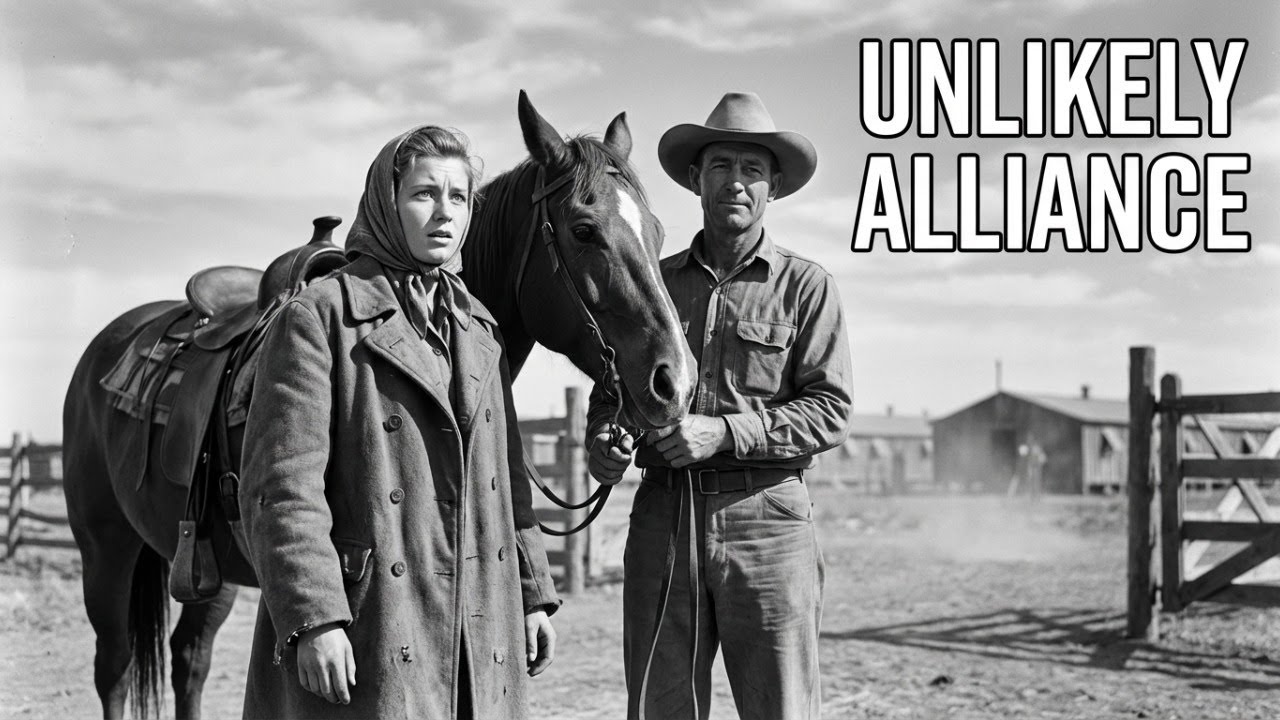

The trucks came to a stop near Heraford, Texas, a small town surrounded by wheat fields and cattle country. This was one of more than 40 prisoner of war camps scattered across the United States. The women blinked in the harsh sunlight as the gates opened. A tall American stepped forward, his boots dusty, a revolver at his side, and a broad cowboy hat shading his eyes.

He looked at the frightened women and said in a slow Texas draw, “You’re in Texas now. We don’t chain people here.” For the women, that line landed harder than any bullet. Inside the camp, they found barracks with real beds, sheets, a mess hall that served warm food. Guards who carried rifles, but also smiled.

The fences were real, yes, but the fear they’d been taught to expect. Wasn’t one prisoner, a young woman named Hilda wrote in her diary that night. I thought they would treat us like animals. Instead, they called us ladies. I do not understand this, America. In the following weeks, that confusion only deepened.

Instead of forced labor, they were asked to help around local ranches. Texas was short on manpower. Most able-bodied men were overseas fighting in Europe or the Pacific. Every hand mattered, even a prisoners. And so, under the burning sun, German women found themselves mending fences, planting crops, sorting grain and weed to their astonishment, learning to ride horses.

The first time Elsa, a Red Cross nurse from Hamburg, was handed a saddle, she froze. I thought it was a trick, she said years later. Why would they let a prisoner sit on a horse? A horse is valuable. But the Texans laughed gently. Ma’am, if you run, where would you go? The nearest town’s 30 mi that way. And with that, they lifted her onto the saddle.

Her hands trembled as she held the reinss. The horse moved forward, and something inside her shifted. For the first time since the war began, she wasn’t obeying an order or fearing punishment. She was simply riding. That was the quiet magic of those Texas camps. The Germans arrived as prisoners of war. But the people around them refused to treat them like enemies.

At night, when the sun dipped low and the plains turned gold, the camp would fill with sounds of home. The women sang all German folk songs, soft and hesitant at first. And sometimes from across the fence, a guard or a cowboy would answer with the slow, mournful tune of a harmonica. Two worlds once at war, blending into a single melody in the Texas dusk.

Letters from families trickled in through the Red Cross. Books written in German appeared in the camp library. The common arant even allowed art supplies, and soon the walls of the barracks were covered in paintings, rivers, forests, cottages, scenes from home. A sergeant once walked into the recreation hall and found a group of German women teaching an American soldier how to write his name in Gothic script.

You know, he said, “My ma would tan my hide if she saw me learning German.” The women laughed, and for a brief moment, the war didn’t exist. But outside the fence, not everyone approved. Some Texans couldn’t understand why the enemy, the same people who had cheered Hitler’s rallies in one, were being treated so well. My boy died in France.

One rancher’s widow said bitterly and they get fresh bread. Yet others saw it differently. In a Sunday sermon, a local pastor told his congregation, “If we show them what decency looks like, maybe they’ll take it home.” And somehow that’s exactly what happened. Months passed. The women worked, learned English, wrote letters, and shared meals with guards who began to feel more like neighbors.

The American guards saw something remarkable. The way fear slowly left the prisoners eyes. By 1945, the war was ending. The camps began preparing for repatriation. For many of the women, leaving Texas was more painful than arriving. One morning, the trucks returned. Orders had come from Washington. They were to be sent home.

As the women packed their belongings, the guards helped quietly, pretending not to notice the tears. When it was time to go, the same cowboys who had once looked at them with suspicion now stood by the fence to say goodbye. Some of the women tossed handkerchiefs into the crowd. Others letters of thanks. One woman, Elsa, the same nurse who had first learned to ride, walked toward the gate.

In her hand, she held a pair of res. The horse had been a gift from the ranch foreman. She dismounted, handed the res back, and said softly, “Freedom is not a place. It’s how you treat people.” That sentence, humble, quiet, unrecorded, was the essence of what those Texas camps had become. Not prisons of war, but classrooms of humanity.

When the women finally returned to Germany, what they found was ruin. Cities bombed to ashes, families scattered. Hunger, despair, and yet buried beneath the destruction, they carried something precious. A strange warmth from across the ocean. the memory of men who had treated them as equals, even when they didn’t deserve it, Hilda Schmidt wrote in her final diary entry.

“I came here as a servant of the furer.” “I left believing in something else. Dignity perhaps, or maybe kindness. I am not sure what to call it, only then it feels like sunlight.” Years later, historians began uncovering these stories. letters, photographs, Red Cross reports, evidence of a quiet, humane chapter in a brutal war.

Over 400,000 German prisoners passed through American camps. And while not all were treated equally, many encountered a version of America that even Americans struggled to live up to. For the women who spent those months in Texas, the experience changed everything. It challenged everything they had been taught about enemies, power, and compassion.

and it left behind a question that still lingers in history shadow. How do you win a war? Not on the battlefield, but in the heart. In the years after the war, some of those women returned to visit America. One wrote to the family of a guard who had once shared his lunch with her. Another sent a painting of the Texas plains, a gift that hung in the Heraford town hall for decades.

For them, Texas wasn’t just a place where they were imprisoned. It was where they learned that decency could survive even in wartime. And perhaps that was America’s quietest victory. Because amid all the battles and bombings, there was a ranch under the endless Texas sky where the defeated met the free and both discovered something far greater than victory.

It wasn’t written in history books. It wasn’t captured in medals, but it was there in every shared laugh, every kind gesture, every moment that defied hate. The wind still moves across those fields today. The fences are gone. The barracks stand empty, but if you listen closely, you might still hear it.

The distant echo of hooves, the soft murmur of a foreign song carried on the wind, and the faint whisper of a truth that outlived the war itself. Sometimes the greatest lesson you can give your enemy is kindness.