At 9:47 a.m. on September 14th, 1965, Lance Corporal Michael Torres crouched in elephant grass 3 miles west of Daang, watching a trail that looked like every other trail in Vietnam. The monsoon had turned the earth to paste. His M14 was slick with humidity. 40 ft ahead, the point man, Private First Class Dennis Chen from San Francisco, moved forward with the slow, deliberate steps of someone who knew that death could be hiding in the next footfall.

In the next 8 seconds, Chen would step on something that would change everything Torres thought he knew about war. The explosion would kill Chen instantly. It would wound four other Marines and it would mark the beginning of the worst week in the history of First Battalion, First Marines.

A week in which bamboo stakes, rusted wire, and mud would prove more lethal than any enemy the United States Marine Corps had ever faced. The official US Marine Corps field manual designated 17 approved methods for detecting and neutralizing enemy booby traps. None of them worked in Vietnam. Battalion intelligence had briefed the company on Vietkong tactics every morning for two weeks.

They knew about punji stakes. They knew about trip wires. They knew that the enemy was using the jungle itself as a weapon. But knowing didn’t mean anything when you were 20 years old, 10,000 m from home, and every step forward could be your last. Chen never saw it coming. Nobody did. One moment he was there, rifle at the ready, eyes scanning the trail.

The next moment there was sound and light, and the smell of blood mixing with cordite and jungle rot. Torres hit the deck. The vegetation around him exploded into chaos. Men were screaming. The radio operator was calling for a medevac. The corman was already running forward, and Torres could see him calculating the terrible mathematics of triage as he moved toward Chen’s body.

But this wasn’t the beginning. This story starts three months earlier in June 1965 when first battalion first marines landed at Dang and learned that everything they’d been trained for was wrong. The Marines had prepared for conventional warfare. They expected to fight the Vietkong the way Americans had fought the Japanese in the Pacific, the way they’d fought the Chinese in Korea.

fire and maneuver, call in artillery, close with and destroy the enemy. Simple, direct. What they found instead was an enemy that refused to fight on American terms. The Vietkong didn’t hold ground. They didn’t mass their forces. They didn’t wear uniforms. They looked like farmers in the morning and disappeared into tunnels by afternoon.

And everywhere the Marines went, the jungle was trying to kill them. The first casualties came on June 27th, 1965. Company Alpha was conducting a routine patrol south of Daang when two Marines triggered a grenade rigged to a trip wire. Both men survived, but the wounds were ugly. Shrapnel in the legs, infection setting in before they even reached the aid. station.

Captain James Morrison, commanding Alpha Company, filed a report that went nowhere. The battalion intelligence officer noted the incident and moved on. Booby traps were a known hazard. This was war. Men got hurt. But Morrison understood something that would take the rest of the battalion months to learn. The booby traps weren’t random.

They weren’t opportunistic. They were strategic. The Vietkong were using them to shape the battlefield to channel American movement to turn every patrol into a nightmare of psychological warfare. The enemy didn’t need to win firefights. They just needed to make the Americans afraid to move. By early September 1965, First Battalion had been in country for 3 months.

They’d lost 11 men killed and 43 wounded. Of those 54 casualties, 40 came from booby traps and mines. The Marines had barely seen the enemy. They’d engaged in three firefights, killed maybe 15 Vietkong, and spent the rest of their time bleeding from wounds inflicted by bamboo wire, and salvaged American ordinance. The frustration was eating the battalion alive.

Sergeants who’d fought in Korea didn’t know how to explain this to their men. How do you maintain morale when the enemy won’t show themselves? How do you fight back against a pit of sharpened stakes? The week that broke first battalion began on September 13th, 1965. Company Bravo was moving through a hamlet near the village of Entra when they found the first trap.

It was elegant in its simplicity. A grenade pinpulled placed inside an empty C-ration can. The safety lever was held in place by the can. A thin wire ran from the can to a stake 30 ft away. When the wire was disturbed, the can would tip. The grenade would fall out. The lever would release and 4 seconds later the fuse would detonate.

The trap killed Private First Class Robert Williams from Philadelphia. He was 19 years old. He’d been in Vietnam for 6 weeks. He tripped the wire reaching for his canteen. The grenade went off at chest height. The corman reached him in 30 seconds and there was nothing to be done. Williams died before the medevac helicopter arrived.

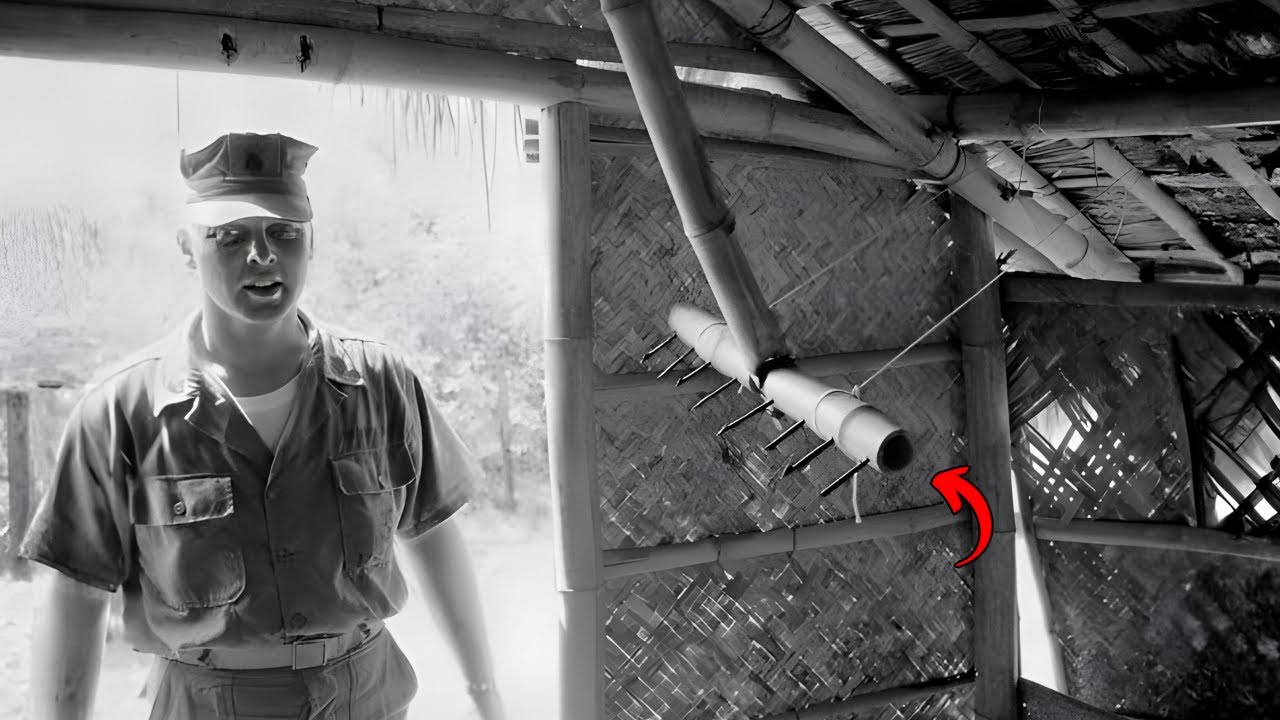

The Marines marked the location. They called in engineers. They moved with more caution. 3 hours later, they found another trap. This one was different. A bamboo whip. The Vietkong had cut a young bamboo tree, maybe 10 ft tall, flexible, and green. They’d bent it back parallel to the ground and secured it with a catch mechanism made from notched wood and vine.

The business end of the bamboo had been fitted with a board studded with 6in spikes sharpened to points and coated with something dark that nobody wanted to identify. A trip wire ran across the trail at ankle height. When the wire was triggered, the catch would release and the bamboo would whip forward at 100 mph, driving those spikes into whoever was standing in its path.

Lance Corporal David Martinez from El Paso saw it. He was walking slack. Second man in the patrol, and something about the way the vegetation looked wrong made him stop. He raised his fist. The column halted. Martinez moved forward slowly, eyes scanning the ground. He saw the wire. He traced it left, then right.

He found the bamboo. He called for the engineers. They spent 45 minutes disarming it. While they worked, the company sat in the open, sweating, listening to the jungle, wondering how many more traps were waiting. They found seven more before sunset. puny pits, cartridge traps, another bamboo whip, a crude directional mine made from an American mortar round.

The Vietkong had turned a two-mile stretch of trail into a killing ground, and First Battalion was walking straight into it. That night, Captain Morrison sat in his hooch and wrote a letter to his wife that he would never send. He tried to explain what it felt like to watch his men die without ever seeing the enemy.

He tried to describe the way fear changed people. How Marines who’d been cocky and aggressive three months ago now moved like old men, checking every step, scanning every shadow, knowing that caution might save them, but wouldn’t guarantee anything. September 14th started with Chen’s death. It got worse. Company Alpha was conducting a sweep three miles west of Da Nang, moving through abandoned rice patties and overgrown trails.

The area had been designated a free fire zone. Intelligence reported no friendly civilians. The battalion commander had authorized the operation based on reports of Vietkong activity in the area. It was supposed to be routine. Find the enemy, fix them in place, call in artillery, clean up the survivors. Instead, they found traps.

The puni pit that killed Chen was a masterpiece of guerilla engineering. The Vietkong had dug a hole 4 feet deep and 3 feet in diameter. They’d planted pungi stakes at the bottom, bamboo spikes sharpened to needle points and angled upward, but they’d also installed stakes along the sides of the pit, angled downward.

When Chen’s weight broke through the camouflage covering, he fell onto the bottom stakes, which drove through his boots and into his feet. When he tried to pull himself out, the side stakes caught his legs and drove deeper. He was trapped, and the Vietkong had coated every spike with human waste. The infection killed Chen, not the fall.

He survived the initial trauma. The corman reached him. They called in a medevac. The helicopter lifted him out. He made it to the hospital ship USS Repose. The doctors tried everything, but the bacteria had already entered his bloodstream. He developed sepsis. His organs began to fail. He died on September 17th, 3 days after stepping on a trap that cost the Vietkong nothing to build and took 2 hours of labor.

While the medevac helicopter was extracting Chen, company Alpha kept moving. The mission hadn’t changed. They had an objective to reach, but now every man in the company was looking at the ground instead of scanning for the enemy. They were moving slower. The interval between Marines had doubled.

The lieutenant in charge was making decisions based on fear rather than tactical doctrine. This was exactly what the Vietkong wanted. At 2:17 p.m., Corporal James Sullivan stepped off the trail to take a leak. He chose a spot behind a tree out of sight of his squad. What he didn’t see was the cartridge trap buried in the soft earth.

The Vietkong had taken a bamboo tube, a nail, a piece of wood, and a single rifle cartridge. They’d positioned the cartridge in the tube with the primer resting on the nail. They’d buried the assembly with just the tip of the round exposed. When Sullivan stepped on it, his weight drove the primer onto the nail. The cartridge fired.

The bullet went through the sole of his boot, through his foot, and lodged in his ankle. Sullivan went down screaming. The corman ran to him. While they worked on Sullivan, the squad set up a defensive perimeter. That’s when someone triggered the secondary trap. The Vietkong had learned that Americans responded predictably to casualties.

They’d rush to help. They’d form up around the wounded man. They’d focus on the injury and forget to watch their surroundings. So, the enemy started placing secondary traps near primary ones, timed or positioned to detonate when the rescue operation was underway. This one was a grenade attached to a delay fuse buried near where Sullivan had fallen.

When the corman knelt to work on Sullivan’s foot, he put his weight on the ground. The pressure triggered the fuse. 3 seconds later, the grenade exploded. The corman took shrapnel in the back and neck. Sullivan took more in his legs. Two other Marines were wounded. And now company alpha had four casualties instead of one.

The medevac helicopter couldn’t land. The area was too hot, too unstable. The company had to move to a clearing 600 m away carrying the wounded on improvised stretchers made from ponchos and rifles. It took them 90 minutes. Every step was agony. Every step could have been another trap. The wounded men were bleeding. Sullivan was going into shock.

The corman was working on his own injuries while trying to keep the others alive, and the Vietkong were nowhere to be seen. By the time the helicopter extracted the casualties, it was nearly dark. Company Alpha had covered less than a mile all day. They hadn’t fired a shot. They hadn’t seen the enemy.

They’d lost five men to traps that cost almost nothing to make and could be constructed by a single Vietkong fighter in less than an hour. The mathematical calculation was devastating. The Vietkong were trading pennies for dollars, and the Americans couldn’t figure out how to stop the exchange. September 15th brought more of the same. Company.

Charlie was conducting a patrol near the Yen River when they walked into what investigators would later determine was a deliberately prepared killing zone. The Vietkong had studied American patrol patterns. They knew the Marines preferred to move along ridgeel lines and avoid the lowlands. They knew Americans would choose trails over thick

vegetation.

vegetation.

They knew the tired men would take the path of least resistance, so they prepared accordingly. The trail looked perfect. Firm ground, good visibility, a direct route to the objective. What the Marines didn’t see was that every 50 m the Vietkong had prepared a trap. Pungi stakes hidden in grass beside the trail, positioned to wound anyone who dove for cover.

Bamboo whips set to trigger if someone left the trail. Grenade traps buried in obviousl looking concealment spots. And at the far end, a command detonated mine made from three American mortar rounds wired together and buried under the trail itself. The first trap got private first class Tommy Walker from Mississippi.

He was walking point and he saw a suspicious patch of ground. He signaled the column to halt. He moved to investigate. He stepped off the trail. His boot came down on a pungi stake that had been planted at a 45° angle point up, camouflaged with a thin layer of leaves. The stake went through his boot, through his foot, and came out the top.

Walker tried to pull his foot free. The stake broke off inside the wound. He fell. When he fell, he landed on three more stakes that had been positioned around the first one. Walker’s screaming brought the corman forward. While they were working on him, the lieutenant made a decision. They couldn’t keep moving forward. The trail was compromised.

They needed to backtrack and find another route. The company began to turn around. That’s when someone triggered the command detonated mine. The explosion killed two Marines instantly. It wounded seven more, and it detonated a secondary cache of grenades that the Vietkong had positioned nearby, extending the kill radius and catching Marines who’d been far enough from the initial blast to survive. The company was pinned down.

They couldn’t move forward. They couldn’t retreat the way they’d come. Artillery couldn’t help because they didn’t know where the enemy was. Air support was unavailable because of weather. For 4 hours, Charlie Company sat in the jungle, treating casualties, calling for medevac, and waiting. When the helicopters finally arrived, they had to hover while Marines carried the wounded through vegetation to a clearing 300 m away.

Three more men were wounded during the extraction when someone triggered another trap. September 16th, September 17th, September 18th. The casualties kept coming. First Battalion lost 37 men in 5 days, 21 killed, 53 wounded, all from booby traps. The battalion had engaged the enemy twice. Brief firefights that lasted less than 10 minutes.

They’d killed four Vietkong confirmed. Maybe the bodies disappeared before anyone could verify. The frustration was metastasizing into something darker. Some Marines were refusing to patrol. Officers were threatening court marshals. Sergeants were trying to hold units together through force of will. The coremen were running out of supplies.

Medevac pilots were getting hit by ground fire every time they tried to land. And back at battalion headquarters, the colonel was receiving casualty reports that he couldn’t explain to division. The booby traps weren’t random. They were strategic. The Vietkong had studied American operations for months. They knew where the Marines patrolled.

They knew which routes they preferred. They knew that Americans moved predictably, that they favored certain types of terrain, that they could be channeled and shaped and herded like cattle to slaughter. The traps were part of a larger system of control. A way to dominate the battlefield without ever showing yourself.

To inflict casualties without risking your own forces. To fight a war where the jungle itself was the enemy, and every shadow could hide death. The bamboo whips were particularly effective. They were silent until triggered. They could be positioned anywhere. They were invisible to mine detectors because they contained no metal.

And they were psychologically devastating. Marines who survived a bamboo whip attack described the same horror. The feeling of being hunted. The knowledge that death could come from any direction at any moment. The sound of the bamboo cutting through air. That split-second warning before the spikes hit. The men who were wounded by bamboo whips rarely returned to combat.

The wounds healed, but the fear didn’t. Pungi stakes were worse in some ways. The injury itself was often minor, a puncture wound in the foot or leg, painful, but survivable. The problem was infection. The Vietkong coated the stakes with human feces, animal waste, and decomposing matter. Every puncture introduced bacteria directly into the bloodstream.

Even with antibiotics, infections were common. Gang green was a constant threat. Men who stepped on pungi stakes could expect weeks in the hospital, multiple surgeries, permanent damage. Some lost their feet, some lost their legs, and every Marine in First Battalion knew it could happen to them on any patrol. The cartridge traps were elegant in their simplicity.

A bamboo tube, a nail, a piece of wood, a single bullet. Total cost, nothing. The Vietkong made them from materials that were lying around in every village. They could plant dozens in an afternoon, and they worked. The bullet fired upward through the soldier’s foot with enough force to shatter bone and sever tendons. The injury was instant and incapacitating.

And because the trap used a standard rifle round, it couldn’t be detected by mine sweepers. By late September 1965, First Battalion was effectively combat ineffective. They lost over 40% of their original strength to booby traps in less than 3 months. Morale had collapsed. Men were refusing orders.

The battalion commander was facing a crisis that no amount of training had prepared him for. How do you fight an enemy you can’t see? How do you maintain unit cohesion when every patrol results in casualties? How do you ask men to keep walking into traps when they know there’s no way to detect them? The Marine Corps response was predictable and inadequate.

They sent in engineers to teach trap detection. They distributed mine detectors that didn’t work on bamboo. They briefed the men on Vietkong tactics. They told them to watch for signs of disturbed earth, unusual vegetation, anything that looked out of place. But the reality was that the Vietkong were better at camouflage than the Marines were at detection.

The traps were invisible until triggered, and by then it was too late. Some units tried to adapt. They stopped using trails. They cut through thick vegetation instead, moving slower, but hopefully avoiding prepared traps. The Vietkong responded by placing traps in the vegetation. They stopped patrolling at night.

The Vietkong started placing traps on the routts between day defensive positions. They varied their patrol patterns. The Vietkong watched and adapted faster than the Americans could change. It was a war of innovation, and the side with less technology was winning. The psychological impact was immeasurable. Marines who’d been confident and aggressive became cautious and fearful.

Men who’d volunteered for point position now tried to avoid it. Squads moved at half speed, checking every step, scanning every shadow. Trust eroded. Soldiers started seeing threats everywhere. Some men refused to leave defensive positions. Others developed what would later be called combat stress reaction, a psychological breakdown characterized by flashbacks, hypervigilance, and an inability to function under stress.

The medical toll was staggering. By October 1965, the hospital ship USS Repose was treating more casualties from booby traps than from combat. The doctors were seeing injuries they’d never encountered before, deep puncture wounds with massive infections, shrapnel injuries from improvised explosives, psychological trauma from watching friends die to invisible threats.

The standard treatment protocols didn’t work. Infections were resistant to antibiotics. Wounds refused to heal. Men were being evacuated back to the United States with injuries that would haunt them for life. First battalion was pulled off the line in early October for rest and refit. They’d been in country for 4 months.

They’d lost 53 men killed and over 150 wounded. Of those casualties, 70% came from booby traps and mines. They’d engaged the Vietkong in exactly seven firefights. They’d killed maybe 30 enemy soldiers, confirmed they’d captured no weapons, no supplies, no intelligence of value. By any measure, it was a disaster.

The afteraction reports were brutal. Battalion intelligence tried to quantify the threat. They documented over 200 separate booby traps found or triggered during the 4-month deployment. They estimated that for every trap found, three more remained hidden. They calculated that the Vietkong could prepare a killing zone for less than a day’s labor and inflict casualties that would take months to recover from.

The mathematics were clear. The United States was losing a war of attrition to an enemy armed with bamboo and wire. But First Battalion’s experience wasn’t unique. Across South Vietnam, American units were encountering the same problem. The Marines in IOR, the area around Daang and Hui, suffered the worst casualties.

Between March 1965 and December 1965, 70% of Marine casualties came from booby traps and mines. In some units, the percentage was higher. A marine company operating west of Daang lost 170 men out of 200 to booby traps in 6 months. They never saw the enemy. They never fired a shot in anger. They just walked through the jungle and bled.

The army units farther south had similar experiences. The 173rd Airborne Brigade lost 40 men to booby traps in a single week. In August 1965, the First Infantry Division reported that mines and traps accounted for 30% of their casualties throughout 1965 and 1966. By 1967, some division commanders were estimating that half of all American casualties in their areas of operation came from booby traps.

The numbers were worse than Korea, worse than World War II, worse than any conflict in American military history. The Vietkong had learned the lessons that the Vietnamese had absorbed over centuries of fighting foreign invaders. You don’t face a superior enemy head on. You don’t hold ground that the enemy can destroy with artillery and air strikes.

You make the enemy afraid to move. You turn their advantages into liabilities. You use the terrain. You use time. You make them bleed for every mile. And you do it with weapons that cost nothing and can be made by anyone with basic materials and a few hours of work. The puni stake was ancient technology. Vietnamese fighters had used sharpened bamboo against Chinese invaders, against Mongol armies, against French colonial troops.

The principle hadn’t changed in a thousand years. Bamboo was plentiful, strong, and easy to work. You could sharpen it with a knife. You could harden it in fire. You could coat it with poison or filth. You could plant it in pits, on trails, in streams, in vegetation. It cost nothing. It required no special training. And it worked. The bamboo whip was an evolution of the same principle.

Use the jungle’s resources against the invader. Bamboo is flexible when young. You can bend it like a spring, store energy in the ark, and release it with devastating force. Add spikes to the impact end and you have a weapon that can kill or maim with a single strike. The Vietkong refined the design over years of trial and error. They learned the optimal height for the trip wire, the best angle for the catch mechanism, the right type of bamboo for maximum speed and impact.

The weapon they created was simple, effective, and terrifying. The cartridge trap showed the enemy’s ingenuity. They took American weapons and turned them against American soldiers. Every patrol that moved through a village left behind brass casings. The Vietkong collected them. Every dud round that didn’t detonate became raw material.

Every mine that was found and disarmed could be salvaged and reused. The Americans were supplying the enemy with the tools of their own destruction, and there was nothing they could do to stop it. By 1966, the Pentagon was forced to acknowledge the scale of the problem. Booby traps were accounting for 15 to 20% of all American casualties in Vietnam, depending on the unit and location.

In some areas, the percentage was twice that. The Marine Corps estimated that mines and traps caused more serious wounds than small arms fire. Medical units were overwhelmed. Medevac helicopters were flying constant missions. Hospital ships were full and the enemy was nowhere to be seen. The institutional response was massive and ultimately inadequate.

The army established mine warfare schools throughout South Vietnam. They trained engineers in trap detection and disposal. They distributed new equipment, better mind detectors, protective gear, manuals on Vietkong tactics. They briefed every incoming unit on the threat. They showed photographs of traps, demonstrated the mechanisms, taught the signs to watch for.

None of it worked as well as they hoped. The problem was that the Vietkong adapted faster than the Americans could teach. Every counter measure was met with a new variation. The Americans started watching for disturbed earth. The Vietkong started camouflaging their traps better. The Americans distributed mine detectors.

The Vietkong used more bamboo and less metal. The Americans trained men to look for trip wires. The Vietkong started using pressure plates and command detonation. It was an arms race fought with stone age technology, and the side with less was winning. Some solutions worked marginally better than others.

Dogs could sometimes smell explosives or detect the scent of humans who’d recently been in an area. But dogs couldn’t be used everywhere and they were vulnerable to their own kinds of traps. Some units adopted the practice of having local Vietnamese walk ahead of patrols. The theory being that villagers would know where the traps were and wouldn’t want to trigger them.

This created its own moral problems and didn’t work reliably. The Vietkong sometimes forced civilians to place traps, knowing they couldn’t warn American patrols without being identified as collaborators. Visual detection was the most effective method, but it required skills that most American soldiers didn’t have and couldn’t learn quickly.

You needed to understand the terrain, to know what looked natural and what didn’t, to recognize the subtle signs that someone had disturbed vegetation or moved earth. The Vietkong who placed the traps were local. They’d grown up in the jungle. They knew every plant, every type of soil, every variation of normal. American soldiers were foreigners.

Even after months in country, most couldn’t match the enemy’s understanding of the environment. The best trap detectors were veterans who’d survived multiple encounters. They developed an instinct, a sense for when something was wrong. They learned to read the terrain the way a Vietkong fighter did.

They understood the enemy’s thinking, the logic of where to place a trap for maximum effect. But creating that expertise required time and experience. And by the time a soldier developed those skills, his tour was often ending. The institutional knowledge walked off the plane every 12 months. And the next rotation of new troops had to start learning from scratch.

The cumulative effect on American operations was profound. Units moved slower. Patrols covered less ground. commanders became risk averse, unwilling to commit troops to areas where booby traps were known to be concentrated. The Vietkong used this to their advantage. They’d saturate certain areas with traps, then operate freely in adjacent areas that the Americans were now avoiding.

The traps didn’t just cause casualties. They shaped the battlefield, channeled American movement, created nogo zones that the enemy could use for rest, resupply, and planning. The cost in resources was also significant. Every booby trap casualty required a medevac helicopter, which meant taking that asset away from other missions.

Every wounded man required medical treatment, sometimes months of it, consuming supplies and personnel. Every trap that was found had to be disposed of, which meant calling in engineers or explosive ordinance disposal teams. The Vietkong could create work for dozens of Americans with a few hours of labor and a handful of materials that cost nothing.

The strategic calculation was elegant. The Vietkong couldn’t match American firepower. They couldn’t win conventional battles, but they didn’t need to. They needed to make the war unsustainable, to drain American will faster than American resources could be brought to bear. Booby traps were perfect for this. They inflicted casualties without risking Vietkong forces.

They consumed American resources without requiring significant enemy investment. They created fear and uncertainty without requiring the enemy to show themselves. And they worked. By 1967, booby traps and mines were causing approximately 4,000 American casualties per year. The number would increase to 5,800 in 1968. At the peak of the war, booby traps were causing more casualties than small arms fire in some units.

In the 20 valard infantry division operating in Kangai province, 90% of casualties in early 1968 came from mines and booby traps. The psychological impact of these statistics was devastating. Soldiers in the division felt that they were being hunted by an invisible enemy, that every step could be their last, that there was no way to fight back.

This sense of helplessness contributed to some of the worst atrocities of the war. When soldiers feel powerless against an enemy they can’t see, when they watch their friends die to traps they can’t prevent. When they operate in a state of constant fear and uncertainty, moral restraints begin to collapse.

The Myai massacre in March 1968 occurred in an area where booby trap casualties had been extraordinarily high. The soldiers involved had watched their friends die to invisible threats for weeks. The violence they inflicted on civilians was inexcusable, but it emerged from a context in which every Vietnamese person was seen as a potential threat, where trust had completely broken down, where the normal distinctions between combatant and civilian had been eroded by fear and frustration.

First battalion, First Marines returned to combat in November 1965. They were reinforced with new troops, mostly young Marines, fresh from training, who didn’t understand what they were walking into. The veterans tried to teach them. They explained the traps. They demonstrated the proper spacing, the right way to move, the signs to watch for, but you couldn’t really prepare someone for the reality.

You had to experience it. You had to watch someone die. You had to feel the fear yourself. And by the time you learned the lessons, you were either dead, wounded, or broken. The battalion’s second deployment was marginally better than the first. Casualty rates from booby traps dropped from 70% to about 50%. This was considered a success.

They developed new tactics. They stopped using trails entirely, cutting through jungle instead. They sent smaller patrols that moved more carefully. They rotated point men more frequently to prevent fatigue errors. They established mine warfare teams within each company who specialized in trap detection. It helped, but men still died.

Every week brought new casualties. Every patrol was a lottery. The Vietkong continued to innovate. They started using secondary and tertiary traps, creating kill chains where the response to the first trap would trigger the second and the evacuation of casualties would trigger the third. They placed traps in helicopter landing zones rigged to detonate when the rotor wash hit them.

They booby trapped bodies, their own and American, knowing that someone would try to recover them. They booby trapped foxholes and defensive positions, anticipating that Americans would reuse them. They studied American behavior and weaponized it. The war of booby traps continued until American ground forces withdrew from Vietnam in 1973.

Over the course of the conflict, mines and booby traps caused approximately 11% of American deaths and 17% of American wounds. More than 65,000 American soldiers were wounded by booby traps during the war. Over 7,000 were killed. These numbers don’t include the psychological casualties, the men who survived physically but were broken mentally, who came home with wounds that never fully healed.

First Battalion, First Marines lost 193 men during their time in Vietnam. 112 of those casualties came from booby traps and mines. The battalion was awarded numerous citations for valor, but no medal could change the fundamental reality of their experience. They fought an enemy they rarely saw. They bled for ground they couldn’t hold.

They learned lessons that cost lives to acquire, and they came home to a country that didn’t understand what they’d endured. Lance Corporal Michael Torres survived the war. He was wounded twice, once by a Punji stake and once by shrapnel from a grenade trap. He spent six months in hospitals. He was medically discharged in 1967 with a Purple Heart and a combat action ribbon.

He returned to San Antonio, Texas, married his high school girlfriend, and worked for the post office for 37 years. He rarely talked about Vietnam. When asked, he’d say he did his job and came home. But every September 14th, he’d receive calls from the men who’d served with him. They’d talk for a few minutes.

Remember Chen, remember the trails west of Daang. Remember the fear and the heat and the feeling of never being safe. And then they’d hang up and go back to their lives, carrying memories that never fully faded. The booby traps of Vietnam changed modern warfare. Military forces around the world studied the tactics.

The improvised explosive device, the IED, which would become the signature weapon of insurgencies in Iraq and Afghanistan evolved directly from the lessons the Vietkong taught in the jungles of Vietnam. The principle remained the same. Use simple materials to create weapons that cause casualties without risking your own forces.

Make the enemy afraid to move. Turn their technological advantages against them. Fight a war where the strongest military in the world can’t bring its power to bear. Modern armies train extensively in countered operations. They’ve developed better detection equipment, better tactics, better medical responses. But the fundamental problem hasn’t changed.

When an enemy is willing to fight asymmetrically, when they use the terrain and civilian populations as cover, when they employ weapons that cost almost nothing and can be made by anyone, conventional military superiority becomes less relevant. You can’t bomb a puny stake. You can’t call in artillery on a bamboo whip.

You can’t use technology to defeat tactics that predate technology. The legacy of Vietnam’s booby traps lives in every conflict where irregular forces face conventional militaries. It lives in the training manuals of armies that learned from the experience. It lives in the tactics of insurgents who studied what worked.

And it lives in the memories of the men who fought there, who learned that the e most dangerous enemy isn’t always the one you can see. That courage sometimes means taking another step forward, even when you know the ground might explode beneath you. That war isn’t always about firepower and technology and superior force. Sometimes it’s about bamboo and wire and the terrible patience of people defending their homeland against invaders who don’t understand the rules of the game they’re playing.

The jungle trails west of Daang are quiet now. The war ended 50 years ago. The puni pits have collapsed. The trip wires have rotted away. The bamboo whips fell back to earth decades ago. But the lessons remain. They’re written in casualty reports and afteraction summaries. They’re recorded in the memories of men who are now in their 70s and 80s, who still remember the fear, who still see their friends falling, who still hear the sound of helicopters and smell the jungle and feel the weight of knowing that every step forward could be the

last one. The traps are gone. But what they taught us about the nature of warfare, about the limits of conventional power, about the ingenuity of desperate people fighting for their homes, those lessons endure. And they’ll endure as long as wars are fought and soldiers learn that the enemy they can’t see is often the most dangerous one of