At 7:32 a.m. on January the 2nd, 1963, Captain Ken Good leaned out of the open door of a CH21 Shaun-e helicopter, watching the rice patties of Appback rush toward him at 90 mph. The morning fog clung to the Meong Delta like wet gauze. He could see the treeine 400 yd ahead, dark and silent, where intelligence said 120 Vietkong were hiding.

The helicopter shuddered as the pilot began the descent. Good checked his M16 one more time. In the next 8 minutes, five American helicopters would be shot out of the sky by an enemy armed with nothing but rifles and machine guns. The tactics that brought them down would change helicopter warfare forever and shatter America’s confidence that technology could win this war.

But nobody in that helicopter knew any of that yet. They were about to land in a carefully prepared killing field that had been waiting for them since dawn. Kenneth Vernon Good was 32 years old that morning. Born in Honolulu, Hawaii, he’d grown up watching the Pacific Fleet come and go from Pearl Harbor. His father worked as a civilian contractor for the Navy, repairing the ships that had survived December 7th, 1941.

Ken was 8 years old when the Japanese attacked, old enough to remember the columns of smoke rising over battleship Row, the sound of anti-aircraft fire that went on for what seemed like hours. The way his mother pulled him and his younger sister into the bathtub and covered them with mattresses because she didn’t know what else to do.

That morning shaped everything that came after. He enlisted in the army at 18, right after high school, because the Navy reminded him too much of burning ships and drowning men. The army meant staying on land, staying in control, staying alive. He went through officer candidate school at Fort Benning, Georgia. Graduated second in his class.

Specialized in infantry tactics and small unit leadership. He was good at reading terrain, understanding how ground and vegetation affected movement and visibility. His instructors noted that he had an intuitive grasp of battlefield geometry, the ability to see how pieces would move before they moved.

By 1962, he’d served nine years, made captain, married a woman named Patricia from Wa Beach, who taught elementary school, and wanted children. They had none yet. The war kept getting in the way. He deployed to South Vietnam in August 1962 as a senior adviser to the Army of the Republic of Vietnam, 7th Infantry Division, stationed in Din Tuang Province in the Meong Delta, 40 mi southwest of Saigon.

His job was to help South Vietnamese commanders plan operations, coordinate American helicopter and air support, and try to win a war against an enemy that refused to fight the way armies were supposed to fight. The seventh ARVN division was considered one of the best in South Vietnam. Its commander, Colonel Huin Vancao, was ambitious, politically connected, and cautious about casualties because President Nin DM measured loyalty by how many soldiers you brought home alive.

Cow’s American adviser was Lieutenant Colonel John Paul Van, a 38-year-old career officer who believed the war could be won through aggressive action and superior firepower. Van had fought in Korea, where he’d learned that hesitation killed more men than boldness. He pushed Cow constantly to engage the enemy, to use the helicopters and armored personnel carriers the Americans were providing, to take the fight to the Vietkong instead of waiting for them to strike first.

By late 1962, the approach seemed to be working. The seventh division claimed to have killed more than 4,000 Vietkong in the last three months of the year, more than any other division in South Vietnam. The Americans were teaching the South Vietnamese how to use mobility and technology to find and destroy an insurgent force. Helicopters were the key.

They let government troops bypass VC ambushes on roads, land in areas the enemy thought were safe, attack from unexpected directions. The CH21 Shauni, called the Flying Banana because of its curved fuselage, could carry 12 soldiers and their equipment into places no truck or boat could reach. The UH1 Huey gunship could provide covering fire with rockets and machine guns.

Together they were revolutionizing how the war was fought. Or so everyone thought. On December 28th, 1962, American intelligence intercepted a Vietkong radio transmission coming from the hamlet of Atonoi in Dinuang Province. The signal was strong and consistent, indicating a fixed transmitter rather than a portable unit. That was unusual.

The vehicle normally moved their radios constantly to avoid detection. A fixed transmitter meant they felt safe, which meant they’d been in the area long enough to get comfortable. Intelligence estimated the transmitter was guarded by approximately 120 VC soldiers, maybe two companies. Van saw an opportunity. A force that size caught in the open could be destroyed with a coordinated attack using helicopters, armored personnel carriers, artillery, and air support.

It would be a demonstration of what American tactics and South Vietnamese execution could accomplish together. He pushed Cao hard to approve the operation. Tao was reluctant. Intelligence about VC strength was often wrong, usually low. But Van was persistent, and Cow finally agreed to commit the Seventh Division to a multi-battalion attack on January the 2nd, 1963.

The plan was textbook. Captain Richard Ziegler, another American adviser, worked with the seventh division staff to draft the operational scheme. An ARVN infantry battalion would fly by CH21 helicopters to landing zones north of Optton Thoi and attack south toward the hamlet.

From the south, two civil guard battalions under the Dinuang Provincial Chief would march north through the rice patties. From the west, an infantry company riding with 13 M113 armored personnel carriers would assault the VC positions once they were fixed by the other forces. The total attacking force numbered about 1,200 troops.

Artillery would be prepositioned to provide fire support. Fighter bombers would be on call. Van would coordinate everything from a small observation plane flying above the battlefield directing the various elements like pieces on a chessboard. The VC caught in a three-sided trap would either be destroyed or forced to flee east across open ground where artillery and air strikes would finish them off.

It was the kind of operation that had worked repeatedly throughout 1962. What nobody knew was that the Vietkong were expecting them. The 261st VC battalion had been operating in the area for months. Its commander, Senior Captain Hang Van Thai, was a veteran of the war against the French, a careful planner who understood that the Americans had given the South Vietnamese two overwhelming advantages.

helicopters that provided mobility and M1 to13 armored personnel carriers that were nearly invulnerable to small arms fire. Most VC units fled when they heard helicopters or saw the M13s, which the gorillas called green dragons because of their color and their seeming invincibility. Hang decided his battalion would do something different.

They would stand and fight. They would prove that determination and proper preparation could defeat American technology. The VC had multiple sources of intelligence about the coming attack. Fam Shuan an a well-connected journalist working for Reuters in Saigon, was actually a deep cover VC agent with access to American and South Vietnamese planning documents.

He’d passed detailed information about ARVN equipment and tactics to VC intelligence officers. Local guerillas in Dinuang Province reported the arrival of 71 truckloads of ammunition and supplies from Saigon on December 30th. An unmistakable sign that a major operation was coming. The VC also intercepted ARVN radio communications because South Vietnamese commanders often failed to use proper encryption or code words.

By the evening of January 1st, Hang knew an attack was coming the next morning, knew the general plan, and knew he had time to prepare. He had approximately 320 regular VC soldiers from two companies of the 200 seat first and 514th battalions plus about 30 local guerillas who would serve as scouts and stretcherbearers. He positioned them along a treeine bordering the hamlet of appachi where the South Vietnamese would have to pass to reach their objective.

The terrain favored the defenders. Rice patties stretched for hundreds of yards on three sides, flat and open, with no cover except the low dikes that separated the fields. Anyone advancing across those patties would be completely exposed. The tree line where Hang positioned his troops was thick with brush and provided excellent concealment.

Behind the trees ran an irrigation canal that would serve as a fallback position if needed. Hong had his men dig fox holes and firing positions along the tree line, spacing them so each position could provide covering fire for its neighbors. He positioned his heavier weapons, including several 30 caliber Browning machine guns captured from ARVN forces to cover the most likely approach routes.

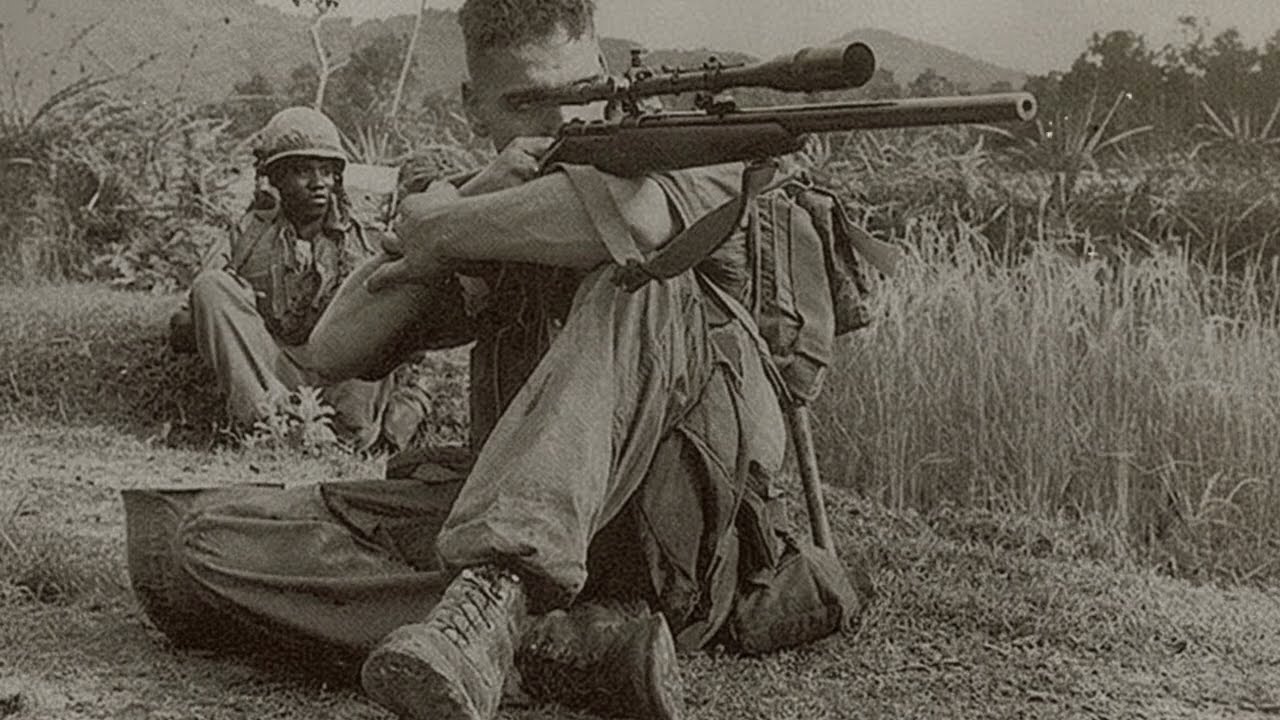

He made his soldiers practice anti-helicopter drills. When helicopters came into land, they were slow, vulnerable, predictable. They hovered or flew at low speed just before touching down. That was when they could be hit. Huang instructed his machine gunners to aim at the helicopter’s transmission housing, the mechanical heart of the aircraft located just above the passenger compartment.

Disable the transmission and the helicopter couldn’t fly. He told them to fire disciplined volleys, not wild spraying. Aimed fire would bring down aircraft. Panic fire would waste ammunition. And then they waited. The night of January 1st was clear and cold. Hang moved among his positions, checking fields of fire, making sure each soldier knew his job.

He told them they were going to make history. They were going to show that the Americans could be beaten, that helicopters could be destroyed, that the Green Dragons could be stopped. His men believed him. They’d been fighting long enough to trust their commander. When dawn broke on January Id, a heavy fog covered the rice patties. Hang smiled.

The fog would delay the helicopters, give his men time to prepare mentally. Let the tension build until they were ready to explode into action. At 6:45 a.m., they heard the first helicopters approaching from the north. The Civil Guard battalions attacking from the south were already in contact, pinned down by VC fire about 100 yardds from the treeine where Huang’s main force waited.

The soldiers could hear the shooting to the south. The sound of M1 Garand rifles and Browning automatic rifles echoing across the patties. But Hangs orders were clear. Hold fire. Let the helicopters land. Let the soldiers get out. Then open fire when they’re most vulnerable. When they’re transitioning from the security of the aircraft to the exposure of the rice patty. That’s when you hurt them.

That’s when you make them understand what this war really is. At 7:30 a.m., the fog began to lift. 10 CH21 helicopters carrying the first company of the ARVN 11th Infantry Regiment approached from the north. Escorted by five UH1 Huey gunships, the formation flew low, maybe 50 feet above the rice patties, the standard altitude for troop insertions.

The pilots couldn’t see the tree line clearly through the morning haze, couldn’t see the foxholes or the machine guns waiting there. They flew toward their designated landing zone, a flat area about 200 yards north of Abbach, the same area they’d landed in dozens of times before during other operations. The same procedures, the same altitude, the same approach pattern, predictable, rehearsed, professional, and therefore vulnerable.

Captain Good was in the lead helicopter, the first to touch down. The pilot, a young warrant officer named Jim Fergesen from the 93rd Transportation Company, brought the CH21 in at a hover about 4 ft off the ground. The crew chief slid the door open. Good prepared to jump out and establish a perimeter while the rest of the ARVN infantry unloaded behind him. That’s when the tree line erupted.

The first burst of machine gun fire hit Ferguson’s helicopter in the transmission housing, exactly where Hong had told his gunners to aim. The transmission seized immediately. The helicopter dropped hard, slamming into the patty at an angle. Good was thrown forward, caught himself on the door frame, felt the impact through his boots and knees as the aircraft hit.

Metal screamed. The rotors were still spinning, but the drive shaft was gone. The helicopter was dead. Good scrambled out, dragged two ARVN soldiers with him, ran toward the nearest dyke, and threw himself behind it. Mud and water splashed across his face. Bullets snapped overhead. That distinctive crack of supersonic rounds passing close.

He looked back and saw the other helicopters scattering, trying to abort their landings, but they were too committed, too low, moving too slowly. The second helicopter took multiple hits to the fuselage and engine compartment. It managed to gain some altitude, maybe 30 ft, before the engine failed completely. The pilot auto rotated down.

A controlled crash into the patty about 50 yards from Good’s position. The helicopter hit hard, flipped on its sade. Good saw soldiers spilling out of the cargo door, some injured, some crawling, some firing their weapons back at the treeine, even though they couldn’t see any targets. The third and fourth helicopters in the formation were hit almost simultaneously.

The third took rounds through the hydraulic system and lost control, crashing nose first into a dyke. The fourth helicopter’s pilot, seeing the carnage ahead, tried to pull up and abort the landing. He gained altitude to about 100 ft before VC fire shredded his tail rotor. The helicopter spun once, twice, three times, then fell out of the sky like a dropped stone.

It hit so hard the landing skids collapsed and the fuselage buckled. The fifth helicopter was the only one that escaped the initial ambush. Its pilot, seeing four aircraft down and the landing zone under heavy fire, pulled full power and climbed out to the east, taking hits but staying airborne. The formation of five UH1 gunships tried to suppress the VC positions, making firing runs along the tree line with rockets and machine guns, but they couldn’t see the enemy troops who were well concealed in their foxholes and firing positions. One of

the Hueies flown by Chief Warrant Officer Charles Gilroy got too low during a gun run. VC machine gunners concentrated fire on the aircraft. Gilroy took multiple rounds through the cockpit. The helicopter lost power and went down, crashing into the rice patty in full view of good and the other soldiers trapped on the ground.

In less than 5 minutes, five American helicopters had been shot down. 15 air crew were dead, wounded or trapped in the wreckage. Dozens of ARVN soldiers were pinned down in the open with no cover except shallow irrigation dikes that provided minimal protection from the sustained machine gun fire coming from the tree line.

Good tried to organize a perimeter, get the ARVN soldiers to return fire, establish some kind of defensive position. But the South Vietnamese troops were scattered, disorganized, many of them in shock from the crash landings and the intensity of the VC fire. Some were shooting wildly in the general direction of the treeine.

Others were trying to burrow into the mud like it might save them. Good moved among them, shouting orders, pulling men into better positions, trying to get his radio working so he could call for help. The radio was soaked, covered in mud, giving nothing but static. He switched to his backup handset, got a partial signal, managed to reach the command post, and report that they were taking heavy casualties, that multiple helicopters were down, that they needed immediate support.

Overhead, Lieutenant Colonel Van circled in his small observation plane, watching the disaster unfold. He could see the downed helicopters, see the soldiers pinned down in the patties, see the muzzle flashes from the treeine where the VC were positioned. He called for artillery fire, directed fighter bombers to make strike runs against the enemy positions, ordered more helicopters to attempt a rescue of the trapped crews and infantry.

The artillery rounds fell, 105 limiter shells impacting along the tree line in explosions of mud and vegetation. The fighter bombers came in F-100 Super Sabers dropping 500 lb bombs and napalm canisters that turned sections of the treeine into walls of flame. But the VC had prepared for this, too. Their foxholes had overhead cover. Their positions were dispersed enough that artillery and bombs couldn’t hit all of them at once.

After each strike, after each bombardment, the machine guns would start firing again. The Americans had the technology. The VC had the will and the preparation. By 8:30 a.m., the Civil Guard battalions attacking from the south had made no progress. They were still pinned down 100 yardds from the treeine, taking casualties every time someone raised their head above a dyke.

The M13 armored personnel carrier force that was supposed to attack from the west hadn’t moved yet. Its commander, Captain Lie Tongba, insisted he needed authorization from higher command before advancing into the battle. The American adviser assigned to BA. Captain James Scandlin was practically begging him to move to use the M113s to rescue the trapped helicopter crews, but bear refused.

He’d been ordered to hold his position until told otherwise, and he wasn’t about to risk his career and his men by violating those orders. Scandlin radioed back to division headquarters to Van to anyone who would listen. People are dying out there. I have to move. Ba wouldn’t budge.

Captain Good, still pinned down behind the dyke, could see one of the crashed helicopters about 30 yards away. The crew was still alive, waving for help, but the VC fire was too heavy for anyone to reach them. Every time an ARVN soldier tried to move forward, machine gun fire would erupt from the treeine and drive them back.

Good realized that without armored support, without some way to suppress or flank the VC positions, they weren’t going anywhere. They were stuck. The VC had planned this perfectly. They’d studied how the Americans operated, learned the patterns, identified the vulnerabilities, and exploited every single one of them.

The helicopters landed in the same place every time. The approach routes were predictable. The tactics hadn’t changed since the first helicopter operations back in early 1962. The VC had been watching, learning, preparing, and now they were executing a masterpiece of ambush warfare. At 9:15 a.m.

, more helicopters arrived to attempt a rescue. Three CH21s and three UH1 gunships flew in from Tan Heap Air Base, having been scrambled as soon as word of the disaster reached headquarters. The pilots knew they were flying into a kill zone, knew that five helicopters had already been shot down, but they came anyway because men were trapped on the ground and the mission was to get them out.

The formation approached from the east, trying a different direction than the original landing, hoping to surprise the VC or find a less heavily defended approach. It didn’t work. The VI simply shifted their fire. The machine guns opened up again as soon as the helicopters came into range. All six aircraft took hits. One of the CH21s piloted by Captain Robert Maize lost its hydraulics and crashlanded in the Patty, becoming the sixth American helicopter destroyed that day.

Maize and his crew survived the crash, scrambled out and joined the growing cluster of stranded Americans and South Vietnamese troops huddled behind whatever cover they could find. The remaining helicopters aborted their landing attempts and pulled away. Their fuselages riddled with bullet holes, hydraulic fluid streaming from severed lines, instruments shattered.

One pilot counted 37 bullet holes in his aircraft when he got back to base. Another had lost all his radios and was flying by hand signals from his crew chief. The UH1 gunships had expended all their ammunition, making ineffective gun runs against enemy positions they couldn’t see or couldn’t hit. The battlefield had become a stalemate.

The VC couldn’t advance across the open ground without exposing themselves to American air power. The Americans and South Vietnamese couldn’t assault the treeine without armored support. and the armored support still hadn’t moved. At 10:45 a.m., nearly 3 hours after the initial ambush, Ban finally convinced Captain Ba to move his M113 force toward the battlefield.

By agreed, reluctantly, but insisted on moving slowly and methodically. The 13 armored personnel carriers began advancing across the rice patties toward Upach. their drivers carefully maneuvering around the deeper sections where the vehicles might bog down. The VC watched them come. Hang predicted this. He’d told his men the Green Dragons would eventually arrive, and when they did, the battle would change.

The M113s were nearly invulnerable to small arms fire. Their aluminum armor could stop rifle rounds and machine gun bullets. The only way to hurt them was to get close enough to throw grenades into the open cargo hatches or to hit them with something heavier than a rifle. The VC had neither. What they did have was discipline and patience. At 1:30 p.m.

, 4 and a half hours after the battle began, the M113 column reached the area where the helicopters had been shot down. The vehicle stopped to pick up survivors and drop off infantry for the assault on the treeine. Captain Good, exhausted covered in mud, his uniform torn and blood stained from helping wounded soldiers, climbed onto one of the M113s.

He briefed the South Vietnamese lieutenant commanding the vehicle, pointed out where he thought the VC positions were located based on the muzzle flashes he’d been watching all morning. The lieutenant nodded. Seemed to understand. The plan was simple. The M113s would advance in a line toward the treeine.

Their 50 caliber machine guns suppressing the enemy positions. The dismounted infantry would follow behind the vehicles, using them as cover, then rush the treeine once they got close enough. It was a tactic that had worked repeatedly throughout 1962. The VC always fled when the M113s arrived, except this time they didn’t. The M113 column advanced to within 50 yards of the tree line.

The VC opened fire with everything they had. Machine guns and rifles all firing at once. The bullets sparked off the armor of the M1 Tartines, ineffective against the metal, but terrifying in their volume and intensity. The dismounted ARVN infantry following behind the vehicles took immediate casualties.

Men dropped, hit by fire they couldn’t see, coming from an enemy they couldn’t locate. The infantry broke, running back toward the downed helicopters away from the killing zone. The M1 and 13 gunners, exposed in their open hatches, became the VC’s primary targets. The vehicles themselves couldn’t be penetrated, but the men operating the 50 caliber machine guns were vulnerable.

VC marksmen began targeting the gunners specifically. One fell, shot through the chest. Another was hit in the shoulder and collapsed into the vehicle. A third took a round through the helmet that somehow didn’t penetrate, but knocked him unconscious. The vehicles began backing up, their gunners [clears throat] dead or wounded, their supporting infantry scattered.

Captain Scandlin, the American adviser, tried to rally the South Vietnamese troops, running forward on foot, pointing toward the treeine, shouting for them to advance. An ARVN lieutenant who spoke English told him, “They will kill you, sir. They will kill all of us.” Scandlin didn’t listen. He kept moving forward until a VC machine gunner put three rounds into the ground at his feet.

He finally understood this wasn’t going to work. The VC weren’t fleeing. They were prepared to fight the M113s, prepared to accept casualties, prepared to die in their positions if necessary. The psychological advantage the Green Dragons had provided for the past year was gone. Captain Good watched the M113 assault fall apart from his position near the downed helicopters.

He’d been fighting for seven hours by then, since 7:30 that morning, and he understood they weren’t going to win this one. The best they could hope for was to hold their positions until dark and then extract under cover of night. He moved among the ARVN soldiers again, trying to organize a defensive perimeter, treating wounded, rationing water and ammunition.

He found Captain Maize, the pilot whose helicopter had been shot down during the second rescue attempt, and together they tried to coordinate with Van, who was still overhead directing air strikes and artillery. Ban wanted one more push, one more assault on the treeine. Good told him it wasn’t going to happen.

The South Vietnamese troops were exhausted, demoralized, pinned down. Another assault would just produce more casualties for no gain. At 2:30 p.m., 8 hours into the battle, General Huin Vancao arrived at the Seventh Division Command post to take personal command of the operation. Xiao was furious. He’d authorized what was supposed to be a simple operation against 120 VC.

and instead he had five helicopters destroyed, three American advisers dead or dying, more than 60 ARVN soldiers killed or wounded, and an enemy force that showed no sign of retreating. He ordered massive artillery barges and air strikes against Appac and the surrounding tree lines. Fighter bombers dropped Napal that turned sections of the hamlet into infernos.

Artillery batteries fired hundreds of rounds, cratering the ground, shredding vegetation, pounding the VC positions with high explosive and white phosphorus. The shelling went on for more than an hour. A demonstration of American firepower that was supposed to destroy anything still alive in those trees.

When the smoke cleared, the VC machine gun started firing again. Not all of them, but enough to make the point. They were still there. They were still fighting. At 4 Crow torn PM, Cow ordered an airborne battalion to drop north of Appach to cut off the VC retreat route. The paratroopers jumped from C123 transports, their parachutes filling the sky like white flowers.

The drop was supposed to land them 500 yd north of the hamlet in position to block the VC’s escape. Instead, because of navigation errors or wind or simple bad luck, they came down right on top of another ARVN unit that was already in position to the north. The paratroopers landed in trees in rice patties scattered across a mile of ground.

Some landed within 100 yards of VC positions and were shot as they descended or before they could get out of their parachutes. Others got hung up in trees and had to cut themselves free while taking fire from the ground. The airborne drop, which was supposed to seal the trap, instead produced more chaos and mo

re casualties. At 5:30 p.m., as the sun began to set over the Mikong Delta, Captain Good got the order to prepare for withdrawal. Helicopters would extract the remaining troops under cover of darkness and artillery fire. The dead would be recovered. The wounded would be evacuated. The operation was over. The VC had won. That night, as darkness fell over the battlefield, the Vietkong slipped away.

They carried their dead and wounded with them, moving east through rice patties and along canals that ARVN forces hadn’t thought to block. By dawn on January 3rd, Appbach was empty. The tree line that had been defended so fiercely was abandoned. The foxholes were empty. The machine gun positions were silent. The VC had fought for an entire day against overwhelming firepower and superior numbers, had shot down five American helicopters and damaged nine others, had killed or wounded more than 150 ARVN soldiers and American advisers, and then

had walked away into the darkness. Captain Kenneth Good didn’t walk away. At 3:45 p.m. on January 2nd, during the seventh hour of the battle, he led a small group of ARVN soldiers in an attempt to reach one of the downed helicopter crews that was still trapped between the ARVN positions and the VC tree line.

They’d made it about 30 yards before VC machine gunners opened fire. Good took three rounds across his chest and neck, fired from maybe 75 yards away by a marksman who’d been waiting all day for someone to make exactly that kind of move. The ARV and soldiers with him dragged him back behind the dyke, but there was nothing they could do.

The wounds were catastrophic. He died within minutes, still trying to give orders, still trying to get his men to safety. They got his body out that night along with the other dead. The army sent his remains home to Hawaii. Patricia Good received the telegram on January. The funeral was on January 12th.

She was 29 years old and pregnant with a daughter she didn’t know she was carrying yet. The army gave her a folded flag and told her that her husband had died a hero, leading his men under fire, trying to save trapped helicopter crews. All of which was true. What they didn’t tell her was that he died in a battle that should never have been fought the way it was fought against an enemy the Americans had underestimated using tactics that the VC had learned to counter.

The battle of Appach ended with 83 South Vietnamese soldiers dead and more than 100 wounded. Three Americans died. Good Sergeant William Deal and Specialist Donald Brahman. Five helicopters were destroyed. Nine more were damaged so badly they required extensive repairs. The Vietkong lost. approximately 18 killed and 39 wounded, though exact numbers were never confirmed.

By any measure of military effectiveness, it was a disaster for the South Vietnamese and their American advisers. But the real damage wasn’t in the casualty figures. It was in what the battle revealed. For more than a year, American commanders in Vietnam had been telling Washington that the war was being won, that the combination of American technology and South Vietnamese troops was steadily defeating the insurgency.

Helicopters were the symbol of that success. They gave the South Vietnamese mobility the VC couldn’t match. Let them strike anywhere, any time with minimal risk. Ape back proved that was an illusion. The VC could shoot down helicopters. They could stand and fight against superior firepower. They could plan and execute complex ambushes that neutralized American advantages.

And they could do it with nothing more than rifles, machine guns, and the will to stay in their positions while bombs and napom fell around them. The American reporters who covered the battle understood what it meant. Neil Sheihan of United Press International, David Halberste of the New York Times, and Peter Arnett of Associated Press had all been at the battlefield or flown over it during the fighting.

They’d seen the downed helicopters. They talked to the angry, exhausted American advisers who’d spent hours watching South Vietnamese commanders refuse to fight or botch operations through incompetence and timidity. Their stories painted a picture that contradicted everything the official military briefers in Saigon had been saying.

Shihan wrote that ARVN troops had refused direct orders to advance, that American advisers were pleading with them to attack while they cowered behind dikes. Halbertom reported that the Vietkong had won a major victory despite being outnumbered and outgunned. Arnett described the battle as a humiliating defeat that exposed fundamental problems with how the war was being fought.

General Paul Harkkins, commander of the military assistance command Vietnam, was furious. He’d been at the battlefield briefly on January II, had talked to reporters and told them the battle was a success, that the VC were trapped and about to be destroyed. When he found out the VC had escaped, and that the reporters were calling it a defeat, he held a press conference to push back.

He insisted that the battle had inflicted heavy casualties on the enemy, that the helicopter losses were acceptable, that the operation had achieved its objectives, even if the VC transmitter hadn’t been captured. Few believed him. The gap between what the military said and what reporters were seeing on the ground was becoming a chasm.

In Washington, President John F. Kennedy read the news reports and began asking hard questions. How could the South Vietnamese, with every advantage, lose to a much smaller VC force? Why were American helicopters so vulnerable? What were the advisers doing if they couldn’t get ARVN commanders to fight? The Secretary of Defense, Robert McNamera, demanded explanations.

The Joint Chiefs of Staff ordered investigations. Everyone wanted to know what had gone wrong at Appback and what could be done to prevent it from happening again. The answer was complicated. Part of the problem was intelligence. The Americans thought they were facing 120 VC when the real number was more than 300. Part was planning.

The operation assumed the VC would behave the way they’d behaved before. fleeing when confronted with helicopters and armored vehicles. Part was execution. The South Vietnamese commanders were too cautious, too slow, too reluctant to take risks that might produce casualties. Part was luck. The morning fog delayed the helicopter insertions, giving the VC time to prepare.

The paratroop drop landed in the wrong place. The M113s took too long to arrive. But the deeper problem was something the Americans didn’t want to acknowledge. The Vietkong were learning. They were studying American tactics, identifying patterns, finding vulnerabilities, and developing counters. The helicopter operations that had been so successful in 1962 worked because they were new, and the VC didn’t know how to respond.

By January 1963, they’d figured it out. The same landing zones used repeatedly, the same approach altitudes, the same flight patterns, the same reluctance to take casualties that made ARVN commanders predictable. The VC learned all of it and planned accordingly. Huang Van Thai, the VC commander at APAC, became a hero in North Vietnam.

His battle plan was studied and replicated by other units. Anti-h helicopter tactics were refined and distributed throughout VC forces operating in the south. Within six months of opback, American helicopter losses began increasing across the country. The tactics that worked in early 1962 became increasingly dangerous by mid 1963.

Pilots had to change their approaches, vary their altitudes, use different landing zones for each operation. Suppressive fire before landing became standard procedure. The casual confidence that had characterized early helicopter operations was gone, replaced by the understanding that every insertion was dangerous, every landing zone could be an ambush.

The CH21 Shaune, the flying banana that had seemed so revolutionary in 1962, was recognized as obsolete. It was slow, it was loud, it was vulnerable. By 1964, it was being phased out and replaced by the UH1 Huey, which was faster, more maneuverable, and better armed. But the fundamental problem remained. Helicopters flying low and slow to insert troops would always be vulnerable to ground fire, no matter how good the aircraft.

The only solutions were to avoid predictable patterns, to use overwhelming suppressive fire, and to accept that losses were inevitable. The men who flew those helicopters knew the risks. Between 1961 and 1975, more than 5,000 American helicopters were destroyed in Vietnam. More than 2,000 pilots died. More than 2,700 crew members were killed.

Being a helicopter pilot or crew chief in Vietnam was one of the most dangerous jobs in the war. The losses at Appbach on January 2nd, 1963 were just the beginning. What made Appach significant wasn’t just the tactical defeat. It was what the battle revealed about the entire war effort. The Americans had superior technology, superior firepower, superior mobility.

But the enemy had superior motivation, superior knowledge of the terrain, and superior patience. The war couldn’t be won by technology alone. It required political will. competent local allies and a strategy that accounted for the enemy’s strengths rather than dismissing them.

Appach showed that none of those conditions existed in South Vietnam in 1963. The political leadership in Saigon was corrupt and unpopular. The military commanders were cautious and political. The troops were poorly motivated and often unwilling to fight. And the Americans, despite their good intentions and massive investment of resources, couldn’t fix those problems by providing better equipment or more advisers.

The Vietkong understood this in a way the Americans didn’t. They knew they couldn’t win through conventional military operations. They didn’t have the firepower or the resources. What they could do was outlast the Americans, make the war so costly and frustrating that eventually the United States would give up and go home.

Every battle like AP back, every helicopter shot down, every operation that ended in failure despite overwhelming advantages pushed that timeline forward. The reporters who covered Appback understood this too. Shihan, Halberste, and Arnett would go on to win Pulitzer prizes for their Vietnam coverage. Their reporting from Appach was part of what earned those awards.

They’d seen through the official optimism and recognized the truth. The war wasn’t being won. The South Vietnamese couldn’t or wouldn’t fight effectively. The American strategy was flawed. And unless something fundamental changed, the United States was heading toward defeat. General Harkkins never forgave them for that reporting. He accused them of being negative, of focusing on failures while ignoring successes, of undermining morale and giving comfort to the enemy.

Other military commanders would echo those complaints throughout the war, but the reporters were right. Appabach was a warning that went unheeded. The battle of Appabach was studied extensively in the years after the war. Military historians identified it as a turning point. The moment when the Vietkong demonstrated they could counter American technological advantages through discipline, preparation, and tactics adapted to local conditions.

The helicopter ambush techniques pioneered at Appbach would be used throughout the war, refined and improved as the VC and later the North Vietnamese army gained access to heavier weapons like the Soviet made 12.7 or DSHK anti-aircraft machine gun and eventually the SA7 Grail shoulder fired surfaceto-air missile.

American pilots learned to respect those weapons and the men who used them. The myth of invulnerability that characterized early helicopter operations was gone forever after app. The battle also influenced how the US military thought about helicopter warfare in general. the lessons from Vietnam, particularly the vulnerability of helicopters to ground fire and the importance of suppressive fire and combined arms operations shaped doctrine for decades afterward.

Modern military helicopters are faster, more heavily armed, and better armored than the CH21s and early UH1s that flew at Abbach. But the fundamental truth remains the same. Aircraft that have to fly low and slow are vulnerable. And the only way to protect them is through careful planning, buried tactics, and acceptance of risk.

For the families of the men who died at back, the battle’s strategic significance was meaningless. Patricia Good raised her daughter alone in Hawaii, never remarrying, never fully recovering from the loss. She kept Kenneth’s medals and letters in a box in her closet, and sometimes late at night, she’d take them out and read them and try to remember exactly what his voice sounded like.

She died in 1994, never having returned to Vietnam, never having seen the battlefield where her husband fell. The daughter she was carrying when Kenneth died, named Karen after his mother, joined the Air Force and served for 20 years as a logistics officer. Determined to honor her father’s service, even though she’d never known him, she retired as a lieutenant colonel.

She visited in 2013, 50 years after the battle, and stood in the rice patties where the helicopters had been shot down. The patties looked the same as they had in 1963. The tree line where the VC had dug their positions was still there, though the trees were different ones now, taller and older. Local farmers worked the fields, planting rice the way their grandparents had done during the war.

Karen wondered if any of them remembered, if any of them had been there that day when the helicopters fell from the sky. She didn’t ask. Some things are better left as memory rather than conversation. The helicopter that Ken Good died trying to reach. The one whose crew was trapped between the ARVN positions and the VC guns was never recovered intact.

It was dismantled and hauled away piece by piece after the battle. its components distributed to maintenance depots and eventually recycled into other aircraft or scrapped. The other four helicopters shot down that day met similar fates. Nothing remains of them now except photographs, official reports, and the memories of men who are themselves mostly gone.

But the tactics that brought them down, the understanding that helicopters could be defeated through discipline and proper preparation survived. Those tactics spread throughout the Vietnamese communist forces and eventually to other insurgent groups around the world who studied Vietnam and learned its lessons. The fundamental dynamic of helicopter warfare, the tension between mobility and vulnerability, remains unchanged.

Lieutenant Colonel John Paul Van, who’d orchestrated the appback operation and watched it fall apart from his observation plane, never accepted the defeat. He blamed the South Vietnamese commanders, blamed their timidity and incompetence, insisted that with better execution, the battle could have been won.

He stayed in Vietnam, left the army in 1963, but returned as a civilian adviser, rose to become one of the most influential Americans in the country, and died in a helicopter crash in 1972, killed not by enemy fire, but by weather and pilot error. His story became one of the central narratives of the American experience in Vietnam.

Documented in Neil Shihan’s book, A Bright Shining Lie. The battle at Appbach appears in that book, one episode in Van’s long and ultimately tragic attempt to win an unwininnable war. The Vietkong commander, Huang Vontai, survived the war and lived until 2010. He never spoke publicly about Abbach in detail. Never gave interviews to Western journalists or historians.

His battle plan and his leadership that day were recognized by the North Vietnamese government. But he remained a quiet figure, uncomfortable with fame, more concerned with living his life than reliving his past. When he died at 88, his obituary in Vietnamese newspapers mentioned AB back but didn’t dwell on it.

One battle among thousands, one small victory in a war that would last another 12 years. The rice patties where the battle was fought are still there. You can visit them if you want. The Vietnamese government has placed a small monument near where the helicopters were shot down. a concrete pillar with an inscription in Vietnamese and English.

It says that here on January the 2nd, 1963, the people’s forces defeated an enemy attack and proved that determination could overcome technology. It doesn’t mention the names of anyone who fought there. It doesn’t give casualty figures. It’s just a marker noting that something happened here once. Something important enough to remember, but not important enough to explain in detail.

Farmers still work those patties, planting and harvesting rice the way they’ve done for generations. The land has forgotten the battle. The dikes where Ken Good died have been rebuilt and reworked a thousand times. The tree line where the Vietkong dug their positions has been cleared and replanted and cleared again as the needs of agriculture dictated.

Nothing remains of that day except in memory and record. And now 60 years later, even the memory is fading. The men who fought there are gone or going. The reporters who covered it have died. The families who mourned have moved on or joined their dead. Soon there will be no one left who remembers Appback firsthand.

No one who can describe the sound of helicopters falling from the sky or the feeling of lying in the mud while machine gunfire cracked overhead. But the lesson remains. Technology alone cannot win wars. Superior firepower means nothing if the enemy refuses to be intimidated by it. Mobility is worthless if your movements are predictable.

And helicopters, no matter how advanced, are still vulnerable to men on the ground who are willing to stand and fight. That’s what the Battle of Abback taught in 1963. And it’s a lesson that every generation has to learn again because the specifics change but the fundamentals don’t. Five helicopters fell at appback.

Three men died trying to save the crews. And a war that would consume 58,000 American lives and reshape a nation continued for another 12 years, long after everyone should have understood that it couldn’t be won the way it was being fought. Sometimes the clearest warnings are the ones we ignore until it’s too late to matter.