John Wayne was mid-draw in a gunfight scene when he saw the man in the wheelchair behind the set barriers and he froze, guns still holstered, 200 crew members waiting, cameras rolling, and he just stared. Wait, because what happened in the next 40 seconds cost the studio $100,000 in lost production time.

But what Jon did over the following 3 weeks would cost him far more. and nobody understood why he couldn’t just let it go. It was June 14th, 1965 on the Monument Valley set of a western called Desert Crossing. The production was already 2 weeks behind schedule and half a million dollars over budget. John Wayne wasn’t just the star.

He was the reason the film existed at all. At 58 years old, he’d built a career playing men who never broke, never bent, never showed weakness. And right now, in the middle of Take 17 of a High Noon Showdown scene, he was supposed to be one of those men. The setup was classic Wayne territory.

Dusty Main Street, wooden buildings on either side, his character facing down three outlaws in black hats. The cameras were positioned perfectly. The light was golden. The director, Martin Cross, had been setting this shot up for 3 hours. 180 extras in period costume lined the street.

The stunt coordinator had choreographed the fall sequences down to the inch. This was the money shot, the scene that would be on every poster in every trailer. Jon had done this dance a thousand times. Draw, fire, bad guys drop. Hero walks away. muscle memory and movie magic. He could do it in his sleep, and he was doing it perfectly until his eyes caught movement in his peripheral vision.

Over by the equipment trucks where the public barriers had been set up to keep curious locals away from the working set, a wheelchair. And in that wheelchair, a man in a faded military jacket trying to see through the crowd of crew members blocking his view. Jon’s hand stopped halfway to his gun.

The scene died mid breath. Martin Cross watching from behind the main camera felt his stomach drop. 200 people on set. Half a million dollars worth of equipment humming. The perfect light that would be gone in 20 minutes. And his star had just gone completely still. “Cut,” Martin said, trying to keep his voice calm.

“John, you okay?” Jon didn’t answer. He was walking toward the barriers. Look, before we go further, you need to understand something about how film sets work. When a major star walks off in the middle of a take, it’s not just an inconvenience, it’s a crisis. Every minute costs money. The union crews are on the clock.

The equipment rentals are ticking. The light is changing. The extras are getting tired. The whole machine grinds to a halt. And somebody has to explain to the studio executives why. Martin followed Jon across the set, his mind already calculating how much this interruption was going to cost. Behind him, the assistant director was frantically talking into his radio.

The crew stood frozen, unsure whether to reset or wait. Jon reached the wooden barriers that separated the working set from the viewing area. About 30 locals had gathered to watch the filming, mostly families, a few kids, some older folks in folding chairs. And there, pushed to the back behind everyone else where he couldn’t see anything, was the man in the wheelchair.

He looked about 60, but it was hard to tell. His face had that worn quality that comes from pain and time. The military jacket was US Marine Corps issue, Vietnam era, too big for his frame. His hands gripped the wheelchair arms with the kind of tension that suggested he’d been sitting there a long time.

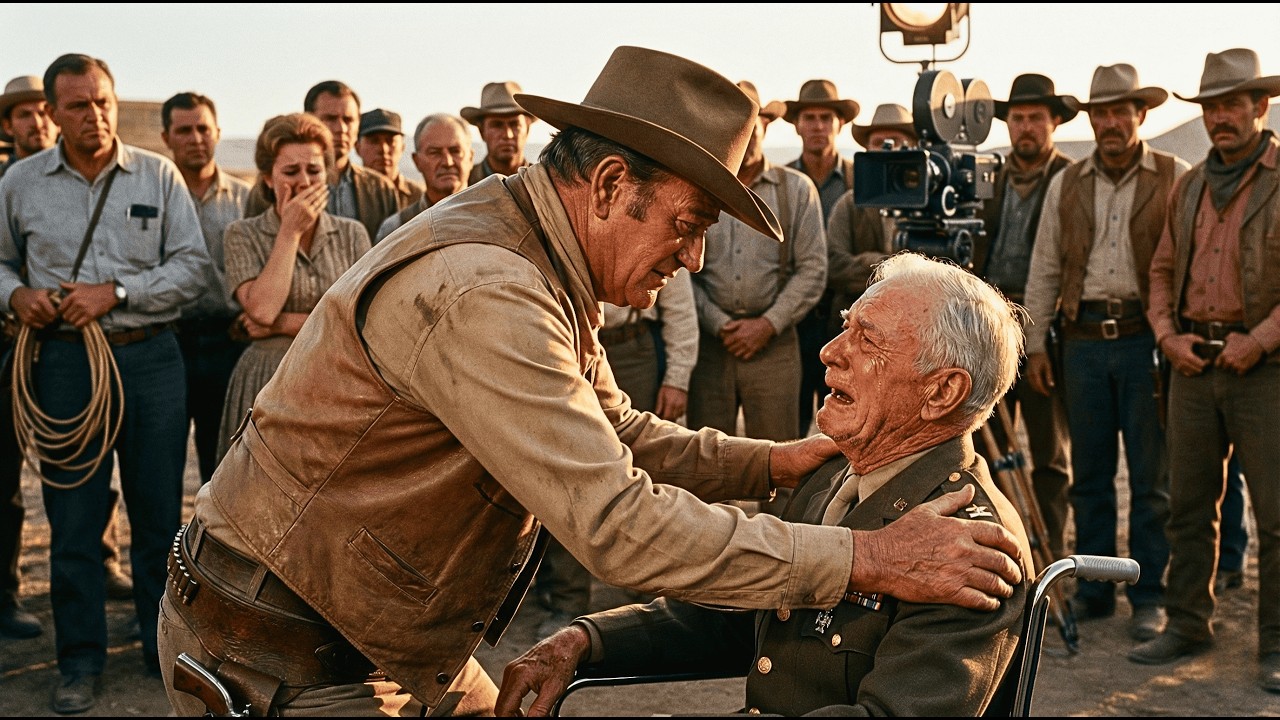

And when he looked up and saw John Wayne walking straight toward him, his eyes went wide with something that looked like fear and hope mixed together. “Sir,” John said, and his voice carried that distinctive rumble that had filled a thousand movie theaters. The man’s mouth opened, but no sound came out. Someone next to him, a woman in her 30s, probably his daughter, put her hand on his shoulder.

Since 6:00 this morning, Mr. Wayne, she said quietly. We drove from Flag Staff. Dad just wanted to see you work. We didn’t mean to interrupt anything. John looked at the barriers, at the crowd of locals blocking the view, at the wheelchair positioned where it couldn’t see the set at all. Then he looked back at Martin Cross who had caught up and was standing behind him looking stressed.

Martin John said we’re done for today. What? John, we haven’t got the shot. We need I said we’re done. The set went quiet. 200 people heard those four words and knew something significant was happening even if they didn’t understand what. Martin pulled Jon aside, lowering his voice. John, we lose this light.

We lose the whole scene. We’d have to rebuild the setup tomorrow. That’s $100,000 in crew time and equipment rental. The studio is already I don’t care what the studio is, John interrupted. His eyes hadn’t left the man in the wheelchair. That marine has been sitting in the sun for 6 hours to watch me play pretend cowboy.

I think we can give him more than a blocked view and a rushed afternoon. remember this moment because it’s where John Wayne made a choice that nobody in Hollywood could quite understand. Not because it was generous. Hollywood had seen generous gestures before, but because of what came next and how far he was willing to take it.

John walked back to the barriers and spoke directly to the Marine. What’s your name, sir? Robert, the managed. Robert Mitchell, First Battalion, Fifth Marines. Robert,” John repeated. He looked at the woman. “And you are, Sarah,” his daughter. Jon nodded, then made a decision that would derail the entire production schedule.

“Robert, Sarah, you’re coming onto the set, not as visitors, as my guests, and we’re not shooting another frame today until you’ve seen everything you came here to see.” The production assistant who overheard this immediately got on the radio to the executive producer. Within 2 minutes, studio executives in Los Angeles were having emergency phone calls.

Within 5 minutes, Martin Cross was being told to get John Wayne back in front of the camera or face serious consequences. Within 10 minutes, none of that mattered because Jon had personally pushed Robert’s wheelchair onto the main set, positioned it right next to the camera, and was refusing to discuss anything else.

Notice what’s happening here. This isn’t a quick photo opportunity. This isn’t a handshake. And back to work. John has stopped the production completely, and he’s about to make it worse. Robert, John said, kneeling beside the wheelchair so they were at eye level. Have you ever seen how a western is made? Robert shook his head, still looking overwhelmed.

Then you’re about to get the full tour. Sarah, you too. I want you to see every part of this. The cameras, the lighting, the stunt setup, everything. And then tomorrow, if you’re willing, I want you both back here as my personal guests for the whole shoot. Sarah started crying.

Robert just stared at Jon like he was seeing something he couldn’t quite believe was real. Martin Cross, standing 20 ft away with a radio pressed to his ear, was getting screamed at by executives who wanted to know why their multi-million dollar production had ground to a halt. He tried explaining about the veteran, about J’s refusal to continue.

The response was predictable. get him back to work or you’re both fired. But here’s what Martin saw that the executives on the phone couldn’t see. He saw the way Robert Mitchell’s hands had stopped shaking when Jon started talking to him. He saw the way the man’s shoulders had straightened slightly.

The way decades of pain seemed to lift just a fraction. And he saw something in John Wayne’s face that he’d never seen in 15 years of working with him. a kind of fierce protectiveness that had nothing to do with the script. Martin hung up the phone and walked over to John. How long do you need? All day, John said simply.

And I want Robert and Sarah here for the rest of the shoot. Every day. Front row seats. John, that’s three more weeks of production. Yes, it is. The studio will lose their minds. Let them. And that’s exactly what happened. Over the next three weeks, Robert Mitchell became a permanent fixture on the Desert Crossing set.

Jon had a special chair positioned right next to the director’s monitor where Robert could see everything. Every morning, Sarah would drive her father from their hotel, paid for by Jon personally, to the set. Every morning, Jon would spend the first 30 minutes walking Robert through what they were shooting that day. The crew, initially resentful about the disruption, gradually came around.

They’d watch Jon explain camera angles to Robert, describe how stunts were coordinated, talk through the emotional beats of scenes. They’d see the way the old Marine’s face lit up during action sequences, the way he’d lean forward in his chair during dramatic moments, completely absorbed, stop for a second, and picture this from Robert’s perspective.

He’d served in Korea in 1951. He’d come home with shrapnel in his spine and legs that barely worked. He’d spent decades in pain, watching John Wayne movies as an escape from a body that had betrayed him and a country that had mostly forgotten he existed. And now he was sitting on a real western set, watching his hero work, being treated not like a charity case, but like an honored guest.

But the studio executives didn’t care about any of that. They cared about budget overruns and schedule delays. Two weeks into the arrangement, they sent a representative to the set with an ultimatum. Robert had to go or they’d pull funding and shut down production entirely. The representative was a studio vice president named Douglas Harmon, a numbers guy who’d never spent a day on an actual set.

He arrived in Monument Valley in a suit that cost more than most of the crew made in a month, found Martin Cross, and demanded to see John Wayne immediately. John was in the middle of a scene when Douglas arrived. He was doing a monologue, a speech about duty and honor and doing what’s right, even when it costs you everything.

The irony wasn’t lost on anyone who knew what was about to happen. Cut, Martin called. That’s the one. Moving on. Douglas intercepted Jon before he could get to Robert’s chair. Mr. Wayne, we need to talk. Jon looked at him, then at Robert, then back at Douglas. Anything you need to say to me, you can say in front of Robert.

This is a business matter. Robert is my business right now. Say [snorts] what you came to say. Douglas glanced around at the crew, clearly uncomfortable with the audience. Fine. The veteran needs to leave the set. Today, this arrangement is costing the studio a fortune in lost productivity, and Robert is staying, John interrupted. Mr.

Wayne, you don’t seem to understand. The board has authorized me to shut down this production if necessary. We have contracts, obligations, and I have a promise, John said quietly. to a Marine who served his country while I was playing dress up in front of cameras. So, here’s what’s going to happen. Robert stays for the rest of the shoot.

And if you have a problem with that, you can shut down the production and explain to your board why you canled a John Wayne Western because you couldn’t handle basic human decency. The set went dead silent. Every crew member within earshot had stopped working. They knew they were witnessing something that would become Hollywood legend one way or another.

Douglas’s face went red. You’re under contract. You can’t. I can. John said. Watch me. Listen. This is where the story could have ended. Studio backs down. Everyone goes back to work. Nice moment of defiance. But what actually happened was more complicated and more costly than anyone expected. Douglas didn’t back down.

He called the studio from the set phone, had a heated conversation with executives in Los Angeles, and came back with a compromise. Robert could stay, but Jon would forfeit his performance bonus for the film, $150,000, about $1.4 million in today’s money, to offset the production costs his guest arrangement was creating.

Jon didn’t hesitate. Done. Sarah sitting beside her father gasped. Robert grabbed Jon’s arm. Mr. Wayne, no. You can’t do that. We’ll leave. I never meant. Jon knelt beside the wheelchair again. Robert, I’ve made more money than I know what to do with playing heroes in movies. This is the first time in a long time I get to actually be one. Let me have this.

Over the final week of production, something shifted in the way Jon approached his work. The crew noticed it first. He started playing his character differently. Less of the invincible cowboy, more of a man who’d seen real loss and chose courage. Anyway, he’d look at Robert between takes, seemed to draw something from the man’s presence, then bring a depth to the scenes that hadn’t been there before.

Martin Cross, who’d been furious about the disruptions at first, found himself filming the best performance John Wayne had given in years. The character in the script was a gunslinger, haunted by his past. Jon was playing him now like a man who understood that real haunting came from real wars, real losses, real choices.

The final day of shooting was bittersweet. The crew had grown attached to Robert’s presence. He’d become a kind of unofficial good luck charm, a reminder of why they were telling stories in the first place. When Martin called the last cut and announced that principal photography was complete, the entire set broke into applause.

Not for the film, but for Robert. John wheeled Robert to center set in front of the whole crew. I want to say something, John announced. This man served in Korea while I was making movies about fake wars. He’s shown more courage sitting in that chair than any character I’ve ever played.

And he’s reminded me that sometimes the most important thing we can do is see people who the world has decided are invisible. Robert was crying. Sarah was crying. But wait, because here’s the part nobody outside that set knew about. After filming wrapped and everyone went home, John didn’t let the relationship end there. He stayed in touch with Robert and Sarah.

Monthly phone calls at first, then visits when Jon was in Arizona. He paid for medical treatments that Robert’s VA benefits didn’t cover. He sent money when Sarah’s car broke down. When her son needed surgery, when the wheelchair lift in their house stopped working. In 1968, 3 years after Desert Crossing wrapped, Jon was producing a documentary about veterans transitioning back to civilian life.

He hired Robert as a consultant, gave him a credit, paid him a real salary. Robert, who’d been living on disability and his daughter’s nursing income, suddenly had purpose again, had work that mattered. The documentary never got wide distribution. But it didn’t matter. What mattered was that Robert Mitchell spent the last years of his life feeling seen, feeling valued, feeling like more than the wheelchair that carried him.

Robert died in 1971, 6 years after that day on the Monument Valley set. John Wayne flew to Flagstaff for the funeral. He gave a eulogy that local newspapers quoted, but that never made national news. In it, he said something that Sarah would later have engraved on Robert’s headstone. Some men play heroes in movies.

Some men are heroes in real life. I was lucky enough to know the difference. After Robert’s death, John established a small fund through the Marine Corps League to help veterans in Arizona with medical expenses and home accessibility modifications. It wasn’t a massive foundation with gallas and press releases.

It was a quiet thing that helped maybe 30 or 40 veterans over the years, paying for wheelchair ramps and heating bills and prescription costs. The fund still exists. It’s called the Robert Mitchell Veterans Assistance Fund, and it’s funded by residuals from Desert Crossing and two other John Wayne westerns. Most people who receive help from it have no idea it’s connected to John Wayne at all.

Desert Crossing was released in March 1966. It made $8 million at the box office. Respectable, but not spectacular. Critics called J’s performance surprisingly nuanced and emotionally rich. Most of them assumed it was just good acting. Martin Cross knew better. In 1978, a film studies professor doing research on John Wayne’s career interviewed Martin about Desert Crossing.

Martin told him about Robert, about the 3-week delay, about Jon forfeiting his bonus. The professor asked if the disruption had been worth it financially speaking. Martin’s answer was simple. The film wouldn’t have been the same without Robert there. Jon needed him. And I think Robert needed Jon. Sometimes the best thing you can do for a movie is remember it’s not about the movie at all.

Now years later, the story of what happened on that Monument Valley set has mostly faded from Hollywood memory. The film itself is rarely screened. The public never knew about the veteran in the wheelchair, about the production delays, about the forfeited bonus. It wasn’t the kind of story that John Wayne wanted publicized. He refused to talk about it in interviews, deflected questions about his charitable work, always changed the subject.

But Sarah Mitchell still has the letters Jon sent her father. She has photos from the set showing Robert next to the camera. Jon kneeling beside the wheelchair, the whole crew gathered around during that final day speech. She has the program from the funeral with J’s eulogy printed inside. and she has a memory of watching her father, a man who’d spent decades feeling invisible and broken, sit in the Arizona sun and laugh at blown takes and bad jokes from stuntmen, feeling useful and seen and alive in a way he hadn’t felt

since before the war. That’s what John Wayne gave Robert Mitchell. Not charity, not pity, but three weeks of being treated like he mattered, like his presence added something instead of taking something away. Three weeks where a man who’d fought in a real war got to sit beside people playing pretend and be reminded that his real sacrifice meant something.

If you enjoyed spending this time here, I’d be grateful if you’d consider subscribing. A simple like also helps more than you’d think. The monument at the Flagstaff Veteran Cemetery where Robert is buried has the quote from J’s eulogy on it. Most visitors probably don’t recognize it. They don’t know the story of the western set or the delayed production or the forfeited bonus.

They just see words about heroes in real life and knowing the difference. But every year on June 14th, the anniversary of that first day Robert came to the set. Someone leaves flowers at the grave. There’s never a card, never a name, just flowers. Sarah suspects it was John those first few years before he died in 1979. After that, she doesn’t know who’s keeping up the tradition.

She likes to think it’s one of the crew members from Desert Crossing. Someone who was there that day when John Wayne walked off a $100,000 shot to push a wheelchair. Someone who remembers that sometimes the most important thing we can do is stop what we’re doing and see who’s been waiting in the back. If you want to hear what happened the night John Wayne got a letter from Robert’s grandson asking about his grandfather’s time on that film set, tell me in the comments.