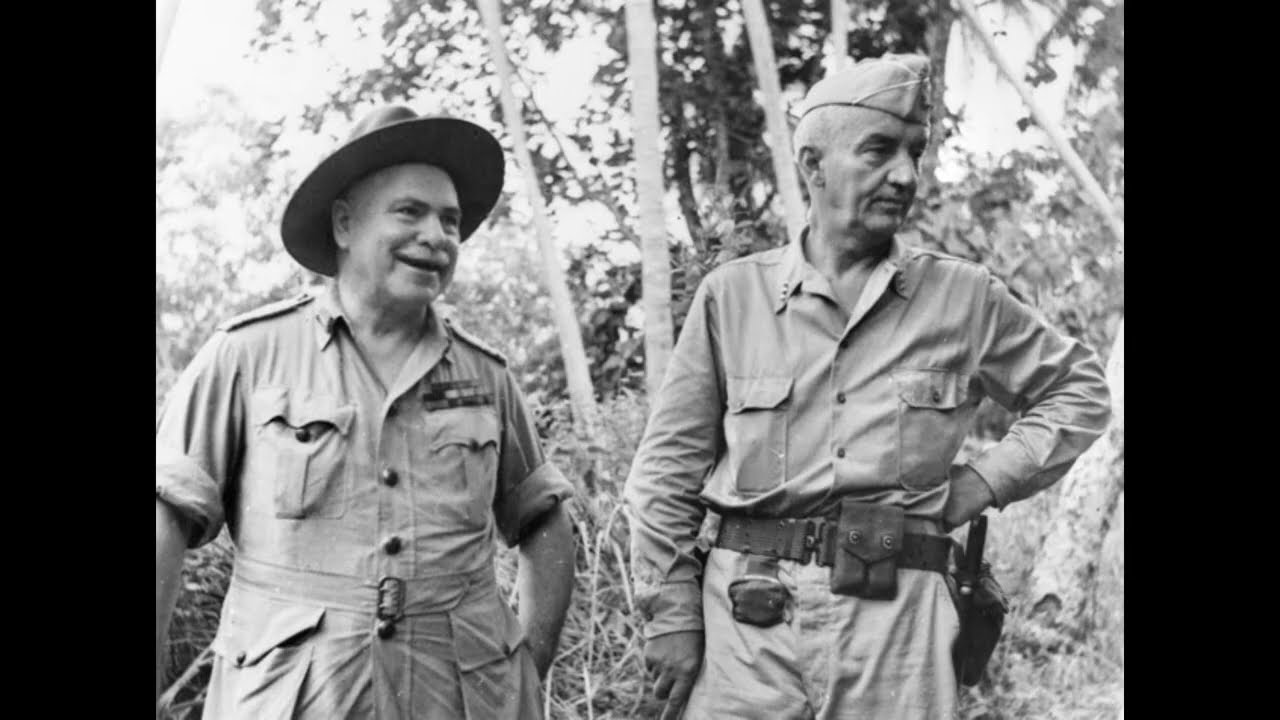

General Douglas MacArthur paced the veranda of government house in Port Moresby. It was November 30th, 1942 and his campaign in New Guinea was falling apart. He had summoned Lieutenant General Robert Eichelberger from Australia. MacArthur needed someone to fix the disaster unfolding at Buuna. The two men stood alone on the veranda.

What MacArthur said next would define Eichelberger’s war and then be used to bury him. MacArthur told Eichelberger he was putting him in command at Buuna. He ordered him to relieve the current commander, a man named Harding. He told him to remove every officer who wouldn’t fight. Then MacArthur leaned closer.

His voice dropped to barely a whisper. He told Eichelberger to take Buona or not come back alive. Then MacArthur pointed at Brigadier General Clovis Buyers, Eichelberger’s chief of staff. “And that goes for your chief of staff, too,” MacArthur added. 5 weeks later, Eichelberger would win one of the most brutal battles of the Pacific War.

“He would save MacArthur’s entire campaign, and then MacArthur would erase him from history.” To understand why MacArthur was desperate enough to threaten his own general, you have to understand what was happening at Buna. The 32nd Infantry Division had been sent to capture the Japanese beach head on the northern coast of New Guinea.

They were National Guard troops from Wisconsin and Michigan. Most had never seen combat. The terrain was a nightmare. Impenetrable swamp. Kunai grass taller than a man. temperatures that never dropped below 90 degrees. The air was thick with the smell of swamp muck and unburied dead. The Japanese had built bunkers from coconut logs and sand.

They were invisible until you walked into the kill zone. American troops were dying before they ever saw the enemy. But the bullets weren’t the worst part. Malaria was cutting through the division like a scythe. Deni fever, dysentery, jungle rot that turned minor cuts into gaping wounds. By late November, the 32nd division was disintegrating.

For every man killed in combat, two or three were being evacuated for disease. Units had stopped advancing. Troops sat in the mud, refusing to move against bunkers they couldn’t see. Officers stayed well behind the lines. The casualty rate, combat, and disease combined would eventually exceed 90% of the division’s original strength, and MacArthur had already told the world he was winning.

MacArthur’s headquarters had been issuing communicates for weeks, claiming victory was imminent. The newspapers back home were printing headlines about MacArthur’s brilliant campaign. The reality on the ground was the opposite. The offensive had stalled completely. Men were dying in the mud while MacArthur’s press releases described a mopping up operation.

Washington was watching. General George Marshall, the Army Chief of Staff, was asking hard questions about why MacArthur’s campaign had bogged down. Meanwhile, the Marines on Guadal Canal were getting all the headlines. The Navy’s campaign was succeeding while MacArthur’s was failing. MacArthur’s political ambitions made this personal.

He was positioning himself for a potential presidential run in 1944. He needed victories and he needed them attributed to him personally. A stalemate at Buuna threatened everything. His reputation, his command, his future. He needed someone to fix this. Someone who could win the battle and then disappear. Robert Eichelberger was about to become that man.

Eichelberger was an unusual choice for a rescue mission. He had spent most of his career in staff positions and military intelligence, but he had one experience that set him apart. In 1918, he had served in Siberia during the Allied intervention in the Russian Civil War. He had worked alongside Japanese forces and understood how they fought.

More importantly, Eichelberger understood something about leadership that many American generals didn’t. He believed officers had to lead from the front, not from comfortable headquarters miles behind the lines. He arrived at the Buuna Front on December 1st, 1942. What he found horrified him. Lines of troops sitting idle in the mud.

No discipline, no forward movement, officers nowhere near the fighting. The division commander, Major General Edwin Harding, was doing his best with impossible conditions. But MacArthur had already decided Harding was the problem. Eichelberger had known Harding since West Point. They had been classmates, friends. None of that mattered now.

MacArthur had given him an order. The next morning, Eichelberger relieved his friend of command. Relieving Harding was just the beginning. Eikleberger spent the next 48 hours tearing through the division’s leadership. He relieved the commander of the 126th Infantry Regiment. He purged the division staff, battalion commanders, company commanders.

MacArthur had told him to put sergeants in charge of battalions if necessary. Eikleberger came close to doing exactly that. The remaining officers understood the message. Fight or be replaced. There was no middle ground. But Eichelberger knew that replacing leaders wouldn’t be enough. The troops had lost faith.

They had watched officers order attacks from the safety of the rear while enlisted men died. To change the battle, Eichelberger would have to change what leadership looked like. He made a decision that his staff thought was suicidal. Eichelberger pinned his silver stars to his collar. Three stars. Lieutenant General, the highest ranking American officer at the front.

His staff begged him to remove them. Japanese snipers would see the stars glinting. He would be the most valuable target on the battlefield. Eichelberger refused. That was exactly the point. He walked upright through positions where his own men were crawling on their bellies. He moved his command post forward until it was within yards of Japanese lines.

The message was unmistakable. If a three-star general could walk through fire, so could they. Eichelberger visited the front lines constantly. He appeared without warning at positions that hadn’t seen an officer in days. Men who had been cowering in foxholes found themselves face tof face with their commanding general asking why they weren’t advancing.

It was leadership by physical presence, leadership by shared risk. And it started to work. Courage alone couldn’t break the Japanese bunkers. Eichelberger needed firepower. And he found it in an unlikely place. Australian Matilda tanks. Heavy, slow, designed for infantry support. Exactly what the Americans needed against fortified positions.

Eichelberger reorganized the supply lines. Instead of relying on coastal boats that kept getting sunk, he flew supplies in by air, food, ammunition, medical supplies. He improved evacuation for the wounded and sick. Men who had been lying in field hospitals for days were finally getting proper care. The combination of aggressive leadership, armor support, and functioning logistics transformed the battle.

Units that had been paralyzed started moving. On December 14th, 1942, Buna village fell to American forces, but the main Japanese stronghold at Buuna Mission held out for three more weeks of brutal fighting. On January 2nd, 1943, the last Japanese resistance at Buna Mission collapsed. After five weeks of command, Eichelberger had won.

The cost was staggering. Roughly 8,500 Allied casualties in the Papua campaign. The 32nd Division had been effectively destroyed as a fighting force. But Eichelberger had accomplished what MacArthur demanded. He had taken Buuna. He had come back alive. Now came the reward he had earned. Recognition, credit, the acknowledgement that he had saved MacArthur’s campaign from disaster.

The headlines appeared in newspapers across America. They described MacArthur’s brilliant victory at Buuna. Eichelberger’s name appeared nowhere. MacArthur made the arrangement explicit. It was a cold transactional betrayal. He told Eikleberger directly that he would get a citation but no publicity. Eichelberger understood what he was hearing. He had won the battle.

MacArthur would take the credit. The mechanics of suppression were already in place. MacArthur’s headquarters controlled every press release that left the theater. His communicates used phrases like Allied forces and MacArthur’s troops. Field commanders were almost never named. The head of MacArthur’s public relations operation was Brigadier General Lrand Diller.

Journalists who tried to write about Eichelberger found their credentials threatened. When reporters asked about the commanders at Buna, they were given nothing. The story was MacArthur’s strategic brilliance. The execution was irrelevant. Eichelberger watched his victory disappear into someone else’s legend.

But the worst part wasn’t being erased once. It was what came next. April 1944, Eichelberger commanded the core level assault on Helandia, a Japanese stronghold on the New Guinea coast. It was a brilliant operation, a massive amphibious envelopment that bypassed Japanese defenses and caught them completely off guard.

Minimal casualties for a major strategic gain. The headlines credited MacArthur’s strategic genius. Eikberger had merely executed orders. Two months later, another crisis. The invasion of Byak Island had stalled under General Horus Fuller. Japanese resistance was fiercer than expected. The timetable was collapsing. MacArthur sent Eichelberger.

The pattern was now undeniable. When operations succeeded smoothly, MacArthur took credit. When they stalled, Eichelberger was sent to fix them. then erased from the story. Eichelberger arrived at Bak and immediately relieved General Fuller. Another commander sacrificed. Another battle to salvage.

He recognized what was happening. MacArthur was using him as a cleaner. The man you send when things go wrong. The man who fixes disasters and then vanishes. In letters to his wife Emma Eichelberger began documenting his frustration. He described himself bitterly as simply being Allied forces in Macarthur’s communicates.

He noted that MacArthur seemed terrified of allowing any rival hero to emerge. The 1944 presidential election was approaching. MacArthur’s name was being mentioned as a potential Republican candidate. A general who won battles and got famous might become a political threat. So Eichelberger won battles and stayed invisible. By late 1944, MacArthur was finally returning to the Philippines.

He had promised to return. Now he would fulfill that promise and secure his place in history. The glory assignment went to General Walter Krueger’s sixth army. They would liberate Luzon and capture Manila. The cameras would be there. The world would watch. Eichelberger’s eighth army received a different mission.

They would mop up the southern Philippines, liberate the southern islands, handle the secondary objectives. MacArthur expected it to take months. It was supposed to be a footnote to the main campaign. Eichelberger turned it into a blitzkrieg. In a matter of weeks, Eichelberger’s 8th Army executed over 50 amphibious landings across the southern Philippines.

He moved faster than anyone at MacArthur’s headquarters thought possible. Mindanao, the Visayas, island after island falling in rapid succession. Japanese forces that expected months to prepare found themselves overrun in days. It was the most aggressive campaign of the Pacific War. Eichelberger was liberating territory faster than the maps could be updated.

MacArthur’s communicates described it as mopping up minor clearing actions. Secondary operations while the real war happened on Luzon. The men dying on those beaches knew better. They weren’t mopping up. They were fighting for their lives in a war their own Supreme Commander claimed was already over.

But the American public would never know. Eichelberger was winning a war that officially wasn’t happening. In his private letters, Eichelberger developed a code name for MacArthur. He called him Sarah after Sarah Burnernhard, the famously dramatic actress. It captured everything Eichelberger had learned about his commander.

the theatrical poses, the calculated publicity, the ego that demanded every spotlight. Eichelberger respected MacArthur’s strategic mind. He acknowledged that the brilliance of the island hopping campaign, the bold decisions that shortened the war, but he loathed the vanity, the communicates that announced light casualties while Eichelberger’s men bled.

The victory declarations issued while soldiers were still dying. It wasn’t just inaccurate, it was insulting to Eichelberger. MacArthur wasn’t fighting a war. He was performing a role while the men in the mud paid the price of admission. The war ended. MacArthur accepted Japan’s surrender on the deck of the USS Missouri, alone in the spotlight as always.

Eichelberger retired as a lieutenant general in 1948. three stars, the same rank he’d held when MacArthur told him to take Buuna or die. In the late 1940s, he began publishing his memoirs. First in the Saturday Evening Post, then in a full book he called Our Jungle Road to Tokyo. Finally, he told his own story.

The book revealed the truth about Buuna, about Helandia and Byak, about 50 amphibious landings dismissed as mopping up, about 3 years of winning battles and being erased. Military historians began reassessing. Many now consider Eichelberger the finest tactical commander in the Pacific theater. Aggressive where others were cautious, innovative where others followed doctrine.

MacArthur’s reputation would eventually crack under the weight of Korea, of Truman firing him for insubordination, of revelations about his ego and his errors. Eichelberger’s reputation only grew. Robert Eichelberger died in 1961. He is buried at Arlington National Cemetery among the soldiers he spent his career leading from the front.

Most Americans have never heard his name. MacArthur’s legend still dominates the Pacific War narrative. The photographs, the corn cob pipe, the dramatic return to the Philippines. But the truth survived. When MacArthur’s campaign stalled, when commanders failed, when battles needed saving, he sent Eichelberger. Take Buuna or don’t come back alive.

Eichelberger took Buuna. He came back alive. He won battle after battle for three years. Then he was erased. The greatest fixer in American military history. The general who was ordered to win or die and then forbidden from being remembered for