December 22nd, 1968. Fire support base Alpine. The smell of rot and cordite hung thick in the monsoon air. Marines are trained to fight men with guns, not shadows with claws. But in the highlands of Kuangtree Province, the real enemy didn’t carry an AK-47. It was 9 ft long, 400 lb, and it could see you in darkness that left Marines blind.

Just 5 weeks earlier, another patrol lost a man to something that moved without sound and killed with surgical precision. Now, platoon Sergeant Richard Gulen’s team was bedding down in the same valley following standard operating procedure. Two-man radio watch, interlocking fields of fire, claymore mines, but all the training in the world meant nothing when the jungle itself was hunting you.

If you’re a veteran watching this, you know these nightmares never left the textbooks. Subscribe for more untold stories from the wars that shaped us. The monsoon had been falling for 3 days straight, turning the red clay around fire support base alpine into a slick that grabbed at boot treads and held them. Platoon Sergeant Richard Gordon pressed his back against the wet bark of a mahogany tree and felt the water seep through his poncho liner, cold against skin that had been damp for so long it felt soft as a baby’s.

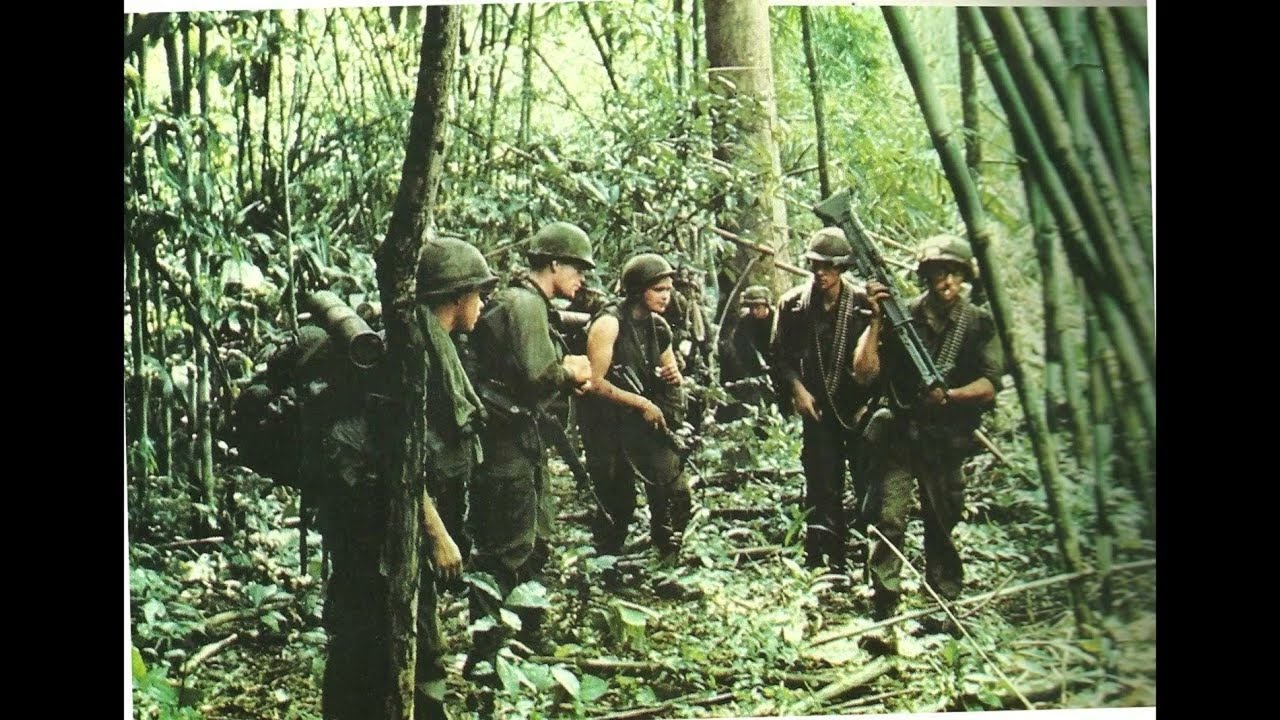

The six-man reconnaissance team had been watching the valley floor since dawn, counting muzzle flashes and radio antennas, logging the movement of North Vietnamese regulars who used the jungle trails like highways. The mission was simple. observe and report. Stay invisible for 72 hours while the enemy walked beneath them, close enough to hear their voices through the canopy.

The team carried everything that mattered strapped to their backs. Ammunition, water, medical supplies, and the NPRC25 radio that weighed 23 lb with its battery, but could reach barely 7 mi through the dense vegetation. In this terrain, 7 miles might as well have been 700 when the cloud sat so low that helicopters couldn’t launch.

Golden shifted his weight and felt a leech, fat as a man’s thumb, drop from an overhead branch onto his neck. He peeled it off without looking, the motion automatic after months in country. The thing left a small wound that would bleed for an hour, mixing with the sweat and rain that ran down inside his flack jacket.

His feet had been wet for so long that the skin between his toes had turned white and begun to peel away in strips. Immersion foot, the corman called it. In 48 hours, if the condition worsened, walking would become difficult. In 72 hours, it might become impossible. The point man, crouched 15 m ahead, raised his fist in the air.

The team froze. Through the steady patter of rain on leaves, Gordon heard what had stopped them. Voices, Vietnamese, male, at least three speakers, maybe four. They were moving along the trail that ran parallel to the ridge line about 60 m below the marine’s position. Gordon pressed his face to the wet earth and peered through a gap in the undergrowth.

Four men in green utilities carrying AK-47s and canvas packs. They walked with the easy confidence of soldiers who owned the ground beneath their feet. The radio man, positioned behind a fallen log, keyed his handset twice. The sound was barely audible, a soft electronic whisper that confirmed the radio was working.

In 6 hours, at the scheduled time, he would make contact with the fire support base and report what they had seen. Until then, the team would remain silent, invisible, and still. Standard operating procedure demanded it. The manual said a reconnaissance team that followed proper camouflage and noise discipline could remain undetected indefinitely.

The manual did not account for tigers. 5 weeks earlier, another patrol from First Battalion, Fourth Marines, had set an ambush near this same valley. Private First Class Francis Baldino, acting as radio telephone operator, had been taken from his fighting position sometime after the 2145 radio check. The search teams found blood on the leaves and deep gouges in the earth where something heavy had been dragged, but they never found Baldino’s body.

The incident was logged as non-hostile action, a bureaucratic designation that meant death by accident or illness rather than enemy fire. The classification offered no comfort to the Marines who continued to patrol these ridges. Gordon had read the afteraction report. The attack had been sudden and silent.

No warning cry, no sound of struggle. One moment, Baldino was maintaining radio watch. The next he was gone, leaving only his weapon and a spreading pool of blood that the rain had washed away by morning. The Marine Corps response had been swift and thorough. A hunting party consisting of five marine snipers and a Vietnamese professional tracker named Fan Vansang had spent two weeks combing the valley for sign.

They found tracks, multiple sets, large paws with retractable claws that left impressions in the soft earth like dinner plates pressed into clay. Adult male Indo-Chinese tigers commonly weighed between 330 and 480 lb. Their canine teeth reached 4 in in length designed to puncture the neck and crush the windpipe in a single bite. They possessed a reflective layer behind their retinas called the tapetum lucidum that allowed them to see clearly in light conditions that left humans functionally blind.

In the dense jungle where the monsoon clouds filtered what little daylight penetrated the canopy, a tiger could observe human movement from a distance of 50 m while remaining completely invisible to its prey. The rain continued to fall, drumming against the broad leaves overhead and running in rivullets down the tree trunks.

Gordon felt the water collect in the small of his back, where his equipment belt created a depression in his poncho. His rifle, an M14 with a 20 round magazine, felt slick in his hands. The weapon was reliable and accurate, but it had been designed to kill men, not 400 lb cats with reflexes faster than human thought.

A tiger could cover 20 ft in a single bound and reach a speed of 40 mph in three strides. At close range, even a perfect shot might not stop the animal before its momentum carried it forward to complete its attack. The causeman, a thin kid from Oklahoma who had been in country for 8 months, checked his watch and held up five fingers.

Five more hours until the scheduled radio contact. Five more hours of lying motionless in the wet undergrowth while leeches found the gaps in their clothing and mosquitoes whed around their ears. The team had positioned themselves in a rough circle, each man responsible for watching a specific sector of approach. They had imp placed two claymore mines along the most likely avenue of enemy approach and positioned themselves so that their fields of fire interlocked without creating a crossfire hazard.

Standard operating procedure assumed the enemy would approach on foot, following established trails and making enough noise to provide advanced warning. It did not account for an enemy that could approach from any direction, moving without sound through terrain that would stop a human patrol. An enemy that hunted by scent and could track the smell of fear, sweat, and gun oil across miles of jungle.

An enemy that killed not for territory or ideology, but simply because warm blood meant survival. As darkness approached, the team settled into their night positions. Two men would maintain radio watch in shifts while the others tried to sleep. The routine was familiar, practiced through dozens of similar missions. What was different this time was the knowledge that somewhere in the darkness below, something with yellow eyes and 4-in teeth might be watching them, waiting for the moment when human alertness dropped just enough to create

an opportunity. In the growing dusk, safety felt as thin as the poncho liner that separated them from the rain, and the jungle pressed in around them like a living thing that had learned to hunt. The attack on Private First Class Francis Baldino happened at exactly 2145 hours on November 14th, 38 days before Gulen’s team would bed down in the same valley.

The time became fixed in the memory of every Marine who heard the story because it marked the moment when standard operating procedure revealed itself as inadequate against an enemy that hunted by instinct rather than tactics. D Company, First Battalion, Fourth Marines, had established three ambush positions along a network of trails that intelligence believed were being used for enemy resupply operations.

The positions were textbook perfect. Good fields of fire, multiple escape routes, and interlocking coverage that would allow the Marines to engage targets from three directions simultaneously. Baldino’s squad occupied the northernmost position. a slight rise overlooking a stream crossing where the trail narrowed between two large boulders.

The evening had proceeded according to routine. The Marines had moved into position during the last hour of daylight, using the fading visibility to mask their approach. They had cleared their fields of fire, positioned their weapons, and settled into the patient waiting that defined ambush operations. The night sounds of the jungle provided a constant background noise.

the chirping of insects, the rustle of small animals moving through the underbrush, and the soft gurgle of water flowing over rocks in the stream bed. Baldino carried the squad’s NPRC25 radio, a responsibility that required him to maintain contact with the company command post at scheduled intervals throughout the night.

The radio checks served multiple purposes. They confirmed that the ambush teams were in position and alert. They provided a means to coordinate fires if contact was made. And they offered psychological comfort to Marines lying alone in the darkness, knowing that help was only a radio call away.

The system worked because it was predictable. Every Marine knew that at 21:45 and again at 23:15 and every hour and a half after that, the radio would crackle with the familiar voices of Marines reporting their status. At 21:45, Baldino keyed his handset and reported negative contact, all secure. His voice carried clearly through the small speaker, calm and professional.

The transmission lasted less than 10 seconds. In the silence that followed, the jungle resumed its normal rhythm of sounds. What happened next took place in absolute quiet. The tiger approached from upstream, moving through the shallow water where its footsteps would make no sound against the rocky bottom. Adult tigers are capable of swimming several miles, and often use waterways as hunting corridors because the sound of flowing water masks their approach, and the wet stones provide better traction than mud or loose leaves.

The animal that stalked Baldino’s position weighed approximately 400 lb and measured 9 ft from nose to tail tip. Its shoulder height reached 40 in, placing its head at the same level as a crouching man. The killing technique employed by large cats has been refined through millions of years of evolution. The initial attack focuses on the neck and throat area where the tiger’s 4-in canine teeth can penetrate between the cervical vertebrae to sever the spinal cord or crush the trachea.

The bite exerts pressure of up to 1,000 lb per square in, sufficient to fracture bone and tear through muscle, cartilage, and major blood vessels simultaneously. Death typically occurs within 30 to 60 seconds through a combination of blood loss, suffocation, and neurological trauma. Baldino never had a chance to cry out.

The tiger seized him from behind, its jaws clamping down on his neck and the base of his skull. The marine’s body went limp immediately as the animals teeth severed his spinal cord between the second and third cervical vertebrae. The tiger then dragged its prey into the stream where the flowing water would wash away the scent of blood and make tracking more difficult.

The entire attack lasted less than 15 seconds. The other members of Baldino’s squad realized something was wrong when they heard a brief scuffling sound followed by a splash. The squad leader, Sergeant Rodriguez, called out Baldino’s name in a harsh whisper. When there was no response, Rodriguez moved toward the radio operator’s last known position, following the sound of the stream.

He found Baldino’s weapon lying on the muddy bank, its sling still warm from contact with human skin. The radio lay partially submerged in shallow water, its antenna bent at an odd angle. Rodriguez immediately initiated emergency procedures. He recovered the radio and established contact with the company command post, reporting one marine missing and requesting immediate support.

The other two ambush teams were ordered to maintain their positions while a quick reaction force was organized at the fire support base. Within 20 minutes, two squads of Marines equipped with starlight scopes and portable flood lights were moving toward Rodriguez’s position. The search began at first light and continued for 3 days. Marines from the battalion reconnaissance platoon joined local Vietnamese scouts in combing the area for any trace of Baldino or his attacker.

They found evidence of the struggle. Deep gouges in the muddy stream bank where something heavy had been dragged, tufts of green fabric caught on thorns, and several clear paw prints in the soft earth beside the water. The prints measured 6 in across and showed the distinctive forto pattern of a large cat. The claws had been retracted during the approach, indicating a stalking behavior rather than a defensive posture.

What disturbed the searchers most was the lack of blood. A human attacked by a large predator typically bleeds extensively, leaving a trail that trained trackers can follow for considerable distances. The absence of such evidence suggested that Baldino had died quickly and that his body had been removed from the immediate area before significant blood loss could occur.

This indicated a level of predatory efficiency that professional hunters recognized as the hallmark of an experienced killer. The incident report filed by D company’s commanding officer described the attack as death due to non-hostile action animal attack. The classification was technically accurate but failed to convey the psychological impact on the Marines who continued to operate in the area.

Word of Baldino’s fate spread quickly through the battalion, carried by radio operators who monitored the search frequencies and by helicopter crews who fed supplies between the scattered fire support bases. Within a week, every marine in the operational area knew that something in the jungle was hunting them and that all their training and equipment offered no protection against an enemy that killed without warning and left no trace of its victims.

The 2145 radio check became a moment of particular vulnerability in the minds of Marines on ambush patrol. It was the last thing Baldino had done before he died, and the time stamp appeared in every subsequent patrol brief as a reminder that death could come at any moment from any direction without regard for standard operating procedure or tactical preparation.

The tiger came for golden at 0230 hours during the deepest part of the night when human alertness naturally ebbed and the jungle pressed closest around the sleeping marines. The attack began without sound or warning, a demonstration of predatory efficiency that 4 million years of evolution had perfected into something approaching mechanical precision.

Gordon had been asleep for less than an hour, his body finally surrendering to exhaustion despite the cold water that had soaked through his poncho liner and the leeches that continued to find exposed skin around his collar and cuffs. The radio man and the point man maintained watch from positions 20 ft away, their eyes straining against darkness so complete that objects more than arms length distant became invisible.

The starlight scope they carried weighed six lb and required ambient light to function effectively. Under the thick canopy and low monsoon clouds, it was useless. The tiger approached from downhill, moving through terrain that would have stopped a human patrol. It navigated around the Claymore mines by instinct rather than detection, following a path that brought it inside the Marines defensive perimeter without triggering any of the early warning devices they had positioned.

The animal moved with absolute silence, its 400-lb body distributed across pores the size of dinner plates that made no sound against the wet leaves and soft earth. Tigers hunt primarily through ambush, using their superior night vision and acute hearing to locate prey before closing to within striking distance. Their eyes contain a reflective layer called the tapetum lucidum that amplifies available light by reflecting it back through the retina.

This biological adaptation allows them to see clearly in conditions that would leave humans functionally blind. In the jungle darkness, the tiger could observe Gordon’s sleeping form from a distance of 30 ft while remaining completely invisible to the Marines on watch. The initial contact lasted less than 3 seconds.

The tiger seized Gordon by the neck and shoulder, its 4-in canine teeth penetrating through the nylon poncho liner and into the muscle beneath. The bite was not immediately fatal because Gordon’s position, lying on his side with his head turned away from the attack, prevented the tiger from achieving the precise neck placement that would sever his spinal cord.

Instead, the animals teeth punctured the trapezius muscle and scraped against his collarbone, creating deep lacerations, but missing the major blood vessels. Gordon came awake instantly. His nervous system flooded with adrenaline that suppressed pain and triggered the fightor-flight response. He felt the massive weight of the animal on top of him and the wet heat of its breath against his neck.

His hands found the tiger’s head, and he attempted to push it away, feeling coarse fur and the ridge of bone above its eyes. The animal’s skull was solid muscle and cartilage beneath the skin, designed to absorb the shock of high impact collisions with prey animals much larger than a human being. The tiger’s next movement followed predatory instinct that had been refined through countless successful hunts.

Unable to achieve a killing bite due to Golden’s struggles, the animal attempted to drag him to a more isolated location where it could reposition for a fatal attack. Tigers typically retreat to dense cover or elevated terrain after seizing prey, both to avoid scavengers and to consume their kill without interference. The nearest suitable location was a bomb crater 15 ft away, carved into the hillside by a 500 lb aerial bomb that had detonated during an earlier operation.

The crater measured approximately 8 ft across and 6 ft deep with steep sides composed of loose red clay that had been pulverized by the explosion. The bottom contained 3 ft of stagnant water mixed with decomposing vegetation that gave off the smell of methane and rotting organic matter. The sides were too steep and slippery for easy climbing, creating a natural trap that would prevent escape once something fell or was dragged to the bottom.

Golden’s struggles intensified as the tiger began pulling him toward the crater. He managed to grab hold of a small tree root with his left hand while striking at the animals head with his right fist. The blows had little effect against the tiger’s massive skull, but they served to disorient the animal and disrupt its grip.

Gordon could feel warm blood running down his neck and chest where the tiger’s teeth had penetrated his skin. The wounds were deep, but not immediately life-threatening, as long as major blood vessels remained intact. The sound of the struggle finally reached the Marines on watch. The radio man heard what he later described as a combination of heavy breathing, fabric tearing, and the distinctive sound of claws scraping against equipment.

He turned toward the noise and saw two shapes moving together in the darkness, one much larger than the other. Without hesitation, he shouted a warning that brought the entire team instantly alert. The pointman reacted first, moving toward the struggle with his M14 rifle at the ready.

In the darkness, he could distinguish Gordon’s voice, calling for help, but could not clearly identify the source of the attack. The other Marines began converging on the position, guided by sound rather than sight. Their training emphasized fire discipline and positive target identification. But these procedures assumed human adversaries who could be distinguished by uniform, equipment, or behavior patterns.

The tiger dragged Gordon over the lip of the bomb crater, and both figures disappeared from view. The Marines could hear the splash as they hit the stagnant water at the bottom, followed by renewed struggling and Gordon’s voice echoing from within the confined space. The crater’s steep sides and circular shape created acoustic properties that amplified sound while making it difficult to determine exact positions.

The corman reached the crater’s edge first and looked down into the black water. He could see two shapes moving in the confined space below, but could not distinguish between marine and animal in the darkness. The tiger’s wet fur appeared black against the dark water, and Gulen’s camouflage utilities blended with the shadows along the crater walls.

The corman called out instructions while the other Marines took positions around the crater’s rim. What followed was a desperate attempt to provide covering fire without hitting Gulen. The Marines fired their M14 rifles into the crater in short, controlled bursts, aiming for muzzle flashes that reflected off the water’s surface and trying to track the larger shape that they assumed was the tiger.

The confined space of the crater amplified the gunshots into ears spplitting explosions that made communication impossible and created a strobing effect that further reduced visibility. The Tiger, wounded by at least two rifle rounds, released its grip on Gulen and attempted to escape by climbing the crater’s slippery walls. The loose clay provided no purchase for its claws, and the animals slid back into the water each time it tried to ascend.

The Marines continued firing, their bullets kicking up geysers of muddy water and ricocheting off the crater’s walls. In the confined space, every shot carried the risk of hitting Gulen. But the alternative was allowing the wounded animal to kill him in the darkness below. The engagement ended when the point man’s rifle fire struck the tiger in the chest and neck, severing major arteries and causing massive internal bleeding.

The animal collapsed into the water and died within minutes, its blood mixing with the stagnant pond at the bottom of the crater. Golden, wounded but conscious, called out that the tiger was dead and requested assistance in climbing out of the pit. The dead tiger lay in 3 ft of black water at the bottom of the bomb crater.

Its massive body creating ripples that lapped against the clay walls with a soft rhythmic sound. Blood from multiple gunshot wounds had turned the stagnant pool dark red in the narrow beam of the courseman’s flashlight. The animal measured 9 ft from nose to tail tip. Its yellow and black striped coat now matted with mud and gore.

Even in death, its physical presence dominated the confined space. A 400-lb reminder that the jungle operated by rules that had nothing to do with military tactics or human technology. Gulen sat in the shallow water beside the carcass, his back pressed against the crater wall while the corman examined his wounds. The tiger’s initial bite had created four deep puncture wounds in his neck and shoulder where the animals canine teeth had penetrated through muscle and scraped against bone.

Blood continued to seep from the lacerations, mixing with the crater water and staining his utilities a darker shade of green. The wounds were serious, but not immediately life-threatening as long as infection could be prevented and blood loss controlled. The corman worked by feel in the darkness.

his hands probing the damaged tissue to assess the extent of injury. The tiger’s teeth had missed the corroted artery by less than an inch, a margin that represented the difference between survival and death in the first 30 seconds of the attack. The punctures were deep enough to require surgical closure, and fragments of torn fabric had been driven into the wounds by the force of the bite.

Without proper medical facilities, infection was almost certain within 24 to 48 hours. Above the crater, the remaining Marines established a defensive perimeter while monitoring radio frequencies for any sign that the gunfire had attracted enemy attention. The sound of automatic weapons fire would carry for miles in the still night air, and North Vietnamese forces in the area would investigate any unusual activity.

The team’s primary mission of remaining undetected had been compromised by the Tiger attack, but their immediate concern was extracting Gordon before his condition deteriorated further. The radio man established contact with fire support base Alpine and requested immediate medical evacuation. The response was not encouraging. Weather conditions remained marginal for helicopter operations with low clouds and intermittent rain that reduced visibility to less than half a mile.

The nearest landing zone capable of accommodating a CH46C knight was more than 2 mi away across difficult terrain, and the pilot would need at least 30 minutes of improved visibility to attempt a night extraction in mountainous country. Getting Golden out of the crater presented immediate practical difficulties.

The walls were too steep and slippery for him to climb unassisted, and his injuries made it impossible for him to support his own weight during a ropeass assisted ascent. The Marines improvised a solution using their poncho liners tied together to form a crude harness. But the process of lifting a wounded man vertically through 8 ft of loose clay was exhausting work that left all of them vulnerable to counterattack.

By the time they had Gordon on level ground, Dawn was beginning to filter through the canopy overhead. The corman had managed to control the bleeding using pressure bandages and gawes from his medical kit. But Gordon’s skin had taken on the pale, clammy appearance that indicated the onset of shock. His pulse was rapid and weak, and he was having difficulty maintaining focus during conversation.

Without intravenous fluids and proper surgical intervention, his condition would continue to deteriorate throughout the day. The tiger’s carcass remained in the crater, too heavy for the small team to extract without mechanical assistance. The sight of the dead animal created conflicting emotions among the Marines who had killed it.

There was satisfaction in having eliminated a threat that had already claimed one Marine’s life, but also a growing awareness that they had encountered something outside their normal sphere of operations. This was not an enemy soldier who could be understood through intelligence briefings or tactical analysis. It was a predator that had been hunting in these valleys for millions of years before the first human set foot in Southeast Asia.

The implications of the attack extended beyond the immediate tactical situation. If one tiger had learned to associate marines with potential prey, others might follow the same behavioral pattern. The animal they had killed was clearly an adult male in prime condition, suggesting a stable population of large predators in the operational area.

Intelligence reports had never mentioned tigers as a significant threat, and no training had been provided on avoiding or dealing with large cat encounters. The Marines were operating in an environment where their most dangerous enemy might not be carrying a weapon. Examination of the tiger’s body revealed additional disturbing details.

Its teeth and claws showed evidence of previous encounters with human equipment. Fragments of green nylon fabric were embedded between its canines, and its front claws bore scratches consistent with contact with military hardware. This suggested that the attack on Gulen was not the animals first interaction with American forces.

It had learned that Marines represented a potential food source and had modified its hunting behavior accordingly. The weight of the dead tiger created logistical problems that extended beyond the immediate extraction. A CH46 helicopter could lift the carcass, but only at the expense of fuel and equipment that might be needed for other operations.

Command elements at three Marine Amphibious Force headquarters wanted physical evidence of the attack for intelligence analysis and public relations purposes. The idea of a tiger killing Marines was politically sensitive information that required careful handling by military sensors and public affairs officers.

As the morning progressed and weather conditions improved marginally, the team prepared for extraction. Gordon’s wounds had stopped bleeding, but his overall condition remained precarious. The corman administered morphine for pain management, but the drug also reduced alertness at a time when the team needed to remain vigilant for enemy activity.

The sound of gunfire during the night would certainly have been reported to North Vietnamese commanders and reaction forces might already be moving toward their position. The extraction helicopter arrived at 10:15 hours, guided to their location by colored smoke grenades that also served to mark their position for any enemy forces in the area.

The CH46 pilot executed a quick approach and landing, keeping his engines running while the crew chief supervised loading of personnel and equipment. Golden was placed on a stretcher and secured inside the aircraft’s cargo compartment, still conscious, but requiring constant medical monitoring during the flight to the nearest field hospital.

The decision to extract the Tiger’s carcass was made at the last moment, driven by command requirements for physical evidence rather than tactical necessity. The crew chief and door gunner used cargo straps to secure the dead animal beneath the helicopter’s external cargo hook, creating an unusual sight that would be photographed and documented for intelligence files.

The combined weight of crew, passengers, and external cargo pushed the aircraft close to its maximum gross weight, requiring careful attention to engine performance during the climb out of the valley. As the helicopter lifted off and turned toward the coast, the Marines looked down at the bomb crater where they had fought for their lives against an enemy that had nothing to do with the larger war being conducted around them.

The jungle closed over the disturbed earth within minutes, erasing all trace of the encounter, except for the blood stains that would eventually wash away in the next monsoon. But the knowledge of what lived in those valleys would remain with every marine who heard the story. A reminder that in some places, humans were still prey.

The CH46 helicopter settled onto the landing pad at Quang Tree Base with the dead tiger suspended beneath its cargo hook. 400 lb of striped death that drew Marines from across the compound to stare in silence. The crew chief released the cargo straps and the carcass dropped to the concrete with a wet thud that echoed off the surrounding bunkers.

Within an hour, a 10-ft scaffold had been erected near the third reconnaissance battalion headquarters, and the Tiger hung by its rear legs like a massive, grotesque trophy that no one wanted to claim. Gulen survived the flight to the field hospital where Navy surgeons spent three hours cleaning debris from his wounds and closing the punctures with surgical thread.

The tiger’s teeth had created four distinct holes in the muscle of his neck and shoulder, each requiring individual attention to prevent infection and ensure proper healing. The doctors administered antibiotics intravenously and tetanus shots as precautions against the bacteria that lived in a large predator’s mouth. His injuries would heal, but the scars would remain visible for the rest of his life.

Four puckered reminders of 30 seconds in a bomb crater. The tiger’s body became an object of scientific and military curiosity that drew officers and enlisted men alike to examine its physical capabilities. A veterinarian from the third medical battalion performed an informal autopsy, documenting bullet wounds and measuring the animals dimensions for intelligence reports.

The canine teeth were exactly 4 in long, designed to puncture through hide and muscle to reach vital organs beneath. The front paws measured 6 in across with retractable claws that could extend 3 in beyond the pad when fully deployed. The shoulder muscles were massive, capable of generating the force necessary to drag a struggling human across rough terrain.

Most disturbing was the evidence of previous encounters with military equipment found in the tiger’s digestive tract. The veterinarian discovered fragments of nylon webbing, pieces of metal consistent with military buttons, and other debris that suggested the animal had consumed parts of military uniforms and equipment. This physical evidence supported the theory that the tiger had killed at least one other person, most likely private first class Baldino, whose body had never been recovered after the November attack.

News of the encounter spread through Marine units across ICOR with the speed that only military communications could achieve. Radio operators monitoring tactical frequencies heard fragments of the story during routine transmissions. Helicopter crews carried details between fire support bases along with mail and supplies.

Within a week, every marine in the northern provinces knew that tigers were hunting American soldiers and that standard operating procedures offered no protection against an enemy that killed by instinct rather than ideology. The psychological impact proved more significant than the actual threat. Marines on ambush patrol found themselves listening for sounds that had nothing to do with enemy soldiers.

The soft pad of heavy feet on wet leaves. The almost inaudible breathing of a large animal. The subtle shift in jungle noise that might indicate a predator moving through the underbrush. Night vision devices and starlight scopes became precious commodities traded between units. Even though their effectiveness was limited by weather conditions and battery life, the knowledge that something was watching from the darkness transformed routine patrol operations into exercises in controlled paranoia.

Command response to the Tiger attacks reflected the military’s institutional difficulty in addressing threats that fell outside established tactical doctrine. Threed Marine Amphibious Force ordered a comprehensive review of wildlife hazards in operational areas, but the resulting reports offered little practical guidance for small unit leaders.

Recommendations included carrying additional medical supplies for treating large animal attacks, avoiding known game trails during movement and maintaining increased vigilance during night operations. The suggestions were sensible but inadequate for addressing the fundamental problem. Marines were operating in an environment where they had become prey.

The organized hunt for additional tigers in the Alpine Valley area produced mixed results that heightened rather than reduced anxiety among ground units. Marine snipers working with Vietnamese trackers found evidence of at least four different animals using the same general area, including paw prints that suggested the presence of at least one female with cubs.

The tracks were fresh, indicating active use of trails that intersected with established marine patrol routes. None of the animals were successfully engaged during the two-week hunting operation, leading to speculation that they had modified their behavior in response to increased human activity. Fan Van Sang, the Vietnamese professional hunter who guided the search teams, provided insights into tiger behavior that proved both informative and unsettling.

Adult tigers typically maintain territories covering 20 to 40 square miles, depending on prey availability and terrain features. A single animal might use dozens of different trails and resting areas within its territory, making prediction of movement patterns nearly impossible. Tigers were capable of detecting human scent from distances exceeding half a mile, giving them enormous advantages in avoiding contact when desired while maintaining surveillance of potential prey.

The seasonal timing of the attacks corresponded with known patterns in tiger behavior that made future encounters more likely rather than less. December and January marked the beginning of the breeding season for Indo-Chinese tigers, a period when territorial disputes and competition for mates, increased aggressive behavior.

Males during this period were more likely to take risks in pursuit of food sources, including investigating new types of prey that entered their territory. The monsoon season also reduced natural prey availability by driving smaller animals to seek shelter, forcing predators to expand their hunting patterns and consider alternative food sources.

Weather patterns that had contributed to the initial attack showed no signs of improvement as the dry season approached. Monsoon clouds continued to limit helicopter operations and reduce visibility for ground units. The combination of limited air support and reduced visibility created conditions that favored predators over humans.

Reversing the technological advantages that usually protected American forces in Vietnam. Radio communications remained reliable, but calls for help meant nothing if extraction aircraft could not launch or locate landing zones in poor weather. Medical facilities in the northern provinces received briefings on treating large animal attacks, a topic that had never appeared in military medical training programs.

Field Cman learned to recognize the signs of hemorrhagic shock caused by major blood loss and the symptoms of infection from bacteria found in predator saliva. Surgical teams practiced procedures for cleaning puncture wounds and dealing with tissue damage caused by crushing injuries. The preparations were thorough and professional, but they represented an acknowledgement that more attacks were expected rather than hoped against.

The Tiger’s carcass remained hanging at third reconnaissance headquarters for 2 weeks, gradually decomposing in the tropical heat until the smell became unbearable and sanitation requirements forced its removal. During those 14 days, it served as a tangible reminder that the jungle operated according to rules that had nothing to do with military planning or human intentions.

Marines would stop to examine the dead animal during their daily routines, running their hands along the massive paws and staring into the yellow glass eyes that death had not dimmed. When the scaffold was finally dismantled and the remains disposed of, the fear remained. Every patrol that moved through the Alpine Valley area carried the knowledge that something might be watching from the shadows, measuring their movements and waiting for an opportunity.

The 2145 radio check became a moment of particular vulnerability. forever associated with Baldino’s death and the realization that death could come without warning from an enemy that had no political objectives or military goals, only hunger and the ancient drive to survive.