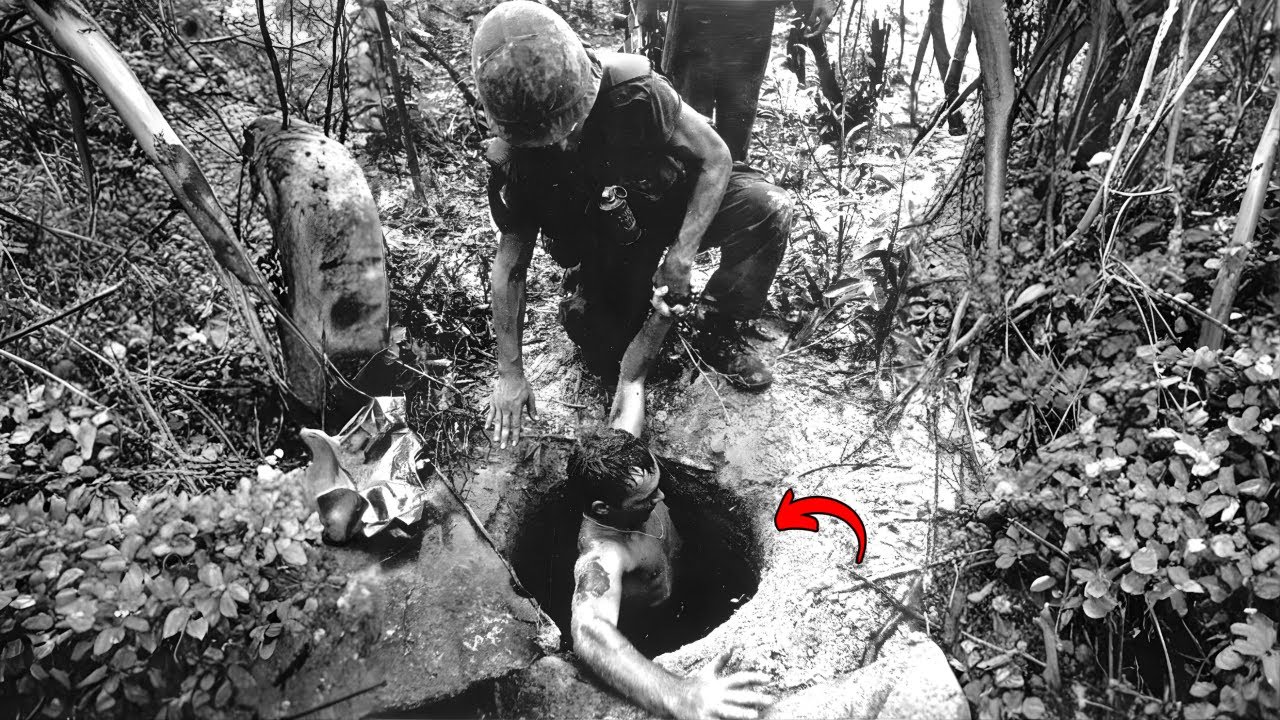

At 8:47 a.m. on January 11th, 1966, Specialist Fourth Class Michael Anthony Reachi crouched at the lip of a tunnel entrance in the Hobo Woods northwest of Saigon, watching the darkness below swallow the beam of his flashlight. He had no radio that would work underground, no backup within shouting distance, no map of what lay beneath his feet, just a Colt 45 pistol with seven rounds, a knife strapped to his boot, and explicit orders from Captain Herbert Thornton that every officer in the First Infantry Division had told him were

tactically unsound and potentially suicidal. In the next 90 minutes, that unauthorized descent into the Earth would reveal an enemy stronghold that changed American understanding of guerilla warfare and cost 11 men their lives in ways no field manual had prepared them for. The official US Army doctrine listed 16 approved methods for clearing Vietkong positions.

Going into the tunnels alone wasn’t one of them. Division Command had discouraged solo tunnel penetration three times in written orders, citing unacceptable casualty rates and intelligence value too low to justify the risk. But doctrine doesn’t mean much when you’ve watched seven men die in two weeks because nobody knows where the enemy goes when the shooting stops.

Richi pulled his helmet off and set it beside the entrance. One chance he waited. Michael Reachi grew up in South Philadelphia where his father ran a corner grocery on 9inth Street. 12-hour days, 6 days a week, margins so thin that spoiled produce meant choosing between heat and food. Michael was the oldest of four, the one who spent summers in the basement instead of the street, learning which crates could take weight, which shelves would collapse, how to maximize storage in spaces designed for half the inventory they

needed. At 18, he was managing the stock room at a warehouse on Delaware Avenue. The work taught him to think in three dimensions, to visualize spaces he couldn’t see, to map connections between rooms by sound and airflow. A loose floorboard meant water damage two levels down.

A draft from the wrong direction meant a wall had been built where the blueprints said there shouldn’t be one. You learned to trust your instincts about spaces because they rarely lied to you the way people did. He enlisted in October 1964, 2 months after his 20th birthday. The recruiter promised technical training, steady advancement, and service far from combat zones.

Richi got 8 weeks of infantry basic, an M14 he’d never wanted, and orders to Vietnam that arrived 3 days after graduation. By the time he reached the first infantry division’s base camp at Li Kay in March 1965, he’d learned that recruiters lied about everything except the shooting. The first infantry division ground its way through the iron triangle like a combine threw wheat.

Every village hid weapons caches. Every treeine concealed snipers. Every trail was mined. But what killed more Americans than enemy? Fire was what came after the fire stopped. The Vietkong would fight for five minutes, inflict casualties, then vanish like smoke. Patrols would sweep the area and find nothing. No bodies, no blood trails, no evidence anyone had been there except the American dead left behind.

Captain Herbert Thornton arrived at Li K in September 1965 with a chemical core background and a problem no one else wanted. The Vietkong were using tunnels. Everyone knew it. Nobody knew how to stop it. The official response was to pump CS gas into any tunnel entrance found, throw in a few grenades, then collapse the entrance with explosives and move on.

simple, efficient, completely ineffective. The tunnels had been designed over 20 years to resist exactly that kind of assault. Multiple entrances meant gas dispersed uselessly. Blast walls absorbed grenade shrapnel. Collapsed entrances could be dug out in hours. Meanwhile, the Vietkong kept disappearing underground, kept calling in mortar fire from positions no one could find, kept moving supplies through networks that seemed to lead everywhere and nowhere at once.

Specialist Jacob Kowalsski died on December 18th, 1965. His patrol encountered Vietkong in a rubber plantation at dawn. The enemy fired for three minutes, then withdrew. Kowalsski’s squad pursued. They found a tunnel entrance hidden under leaves and roots. Kowalsski tossed two grenades down the hole. Nothing.

He reported the tunnel to battalion, marked it on his map, and continued the patrol. That night, Vietkong emerged from that same tunnel, crept to within 30 yards of Kowalsski’s position, and opened fire. Kowalsski took rounds in the neck and chest. He was 22 years old from Detroit, a machinist before the war. He’d planned to go to trade school after his tour.

His father would receive the telegram on Christmas Eve. Private first class David Chen died on December 27th, 1965. Another tunnel, another patrol. Chen was a radio operator, the man everyone depended on to call for support when things went wrong. He was checking a suspicious pile of leaves when the ground beneath him collapsed.

He fell 12 ft into a spider hole that connected to a larger tunnel network. By the time his squad pulled him out, he’d been shot twice by a Vietkong fighter who’ fired from a concealed position, then disappeared deeper into the tunnels. Chen died on route to the aid station. He was 19, born in San Francisco, spoke better Cantonese than English, always shared his cigarette rations even though he didn’t smoke.

The Vietkong who shot him was never found. Corporal Samuel Washington died on January 3rd, 1966. His platoon was conducting a sweep through the Hobo Woods when they discovered a tunnel complex. Washington volunteered to check the entrance. He went in with a flashlight and a pistol. His squad heard three shots, then silence.

They pulled him out 4 hours later after pumping smoke into every entrance they could find. He’d been shot once in the head from point blank range, probably within the first minute of entry. The Vietkong had booby trapped his body with a grenade. Two men were wounded removing it. Washington was from Alabama. He’d been in country for 7 months. He had 43 days left on his tour.

By early January 1966, the First Infantry Division had lost 19 men to tunnel related incidents in three months. Not battles, not ambushes in the conventional sense, just soldiers who went into dark holes and never came out the same way, if they came out at all. Richi had known Kowalsski personally. Chen had been assigned to his company.

Washington had taught him how to read terrain, how to spot false trails, how to keep your weapon dry in the monsoon. Each death felt preventable. Each death made him angrier. The official response from division was predictable. Maintain search protocols. Use gas and grenades. Mark tunnel locations for destruction by engineers.

Do not, under any circumstances, send soldiers into the tunnels without explicit authorization and proper support. Captain Thornton held a meeting after Washington died. 30 exhausted soldiers in a tent that smelled like mildew and diesel fuel. Higher command is acknowledging the tunnel problem. Thornton said his uniform was cleaner than theirs.

He’d spent the morning at division headquarters. We’re developing new protocols for tunnel clearance. Until then, maintain current procedures and avoid unnecessary risks. Richi stood near the back. He’d been thinking about the problem for weeks. The Philadelphia warehouse had taught him that you couldn’t understand a space by looking at it from outside.

You had to go in, map the connections, see how the pieces fit together. The Vietkong knew those tunnels like he’d known his father’s basement. Every turn, every chamber, every way in and out, Americans were fighting blind. Sir Reachi said, “What if we sent someone in just to map the tunnels, see what we’re dealing with?” Thornton looked at him like he’d suggested using his head as a battering ram.

Specialist, the tunnels are death traps. We don’t have training for that kind of operation. We don’t have equipment. We don’t have doctrine. But sir, if we could just Reichi didn’t finish. Thornton cut him off. The answer is no. We’re not sending men into those tunnels to satisfy curiosity. Dismissed. Reachi said nothing, but he didn’t forget.

The tunnels kept swallowing soldiers. The official methods kept failing. And somewhere beneath the jungle floor, the Vietkong were building an empire in the dark that no one seemed able to touch. On the night of January 8th, 1966, Richi made his decision. Operation Crimp had begun. 8,000 American and Australian troops were sweeping the Hobo Woods and the Iron Triangle, the largest operation of the war so far.

B-52s had carpet bombed the area for two days. Infantry was moving through in companysized elements, searching for Vietkong bases and tunnel entrances. Reachi’s company was dug in along a tree line two miles from the main thrust. They’d found three tunnel entrances that afternoon. Standard procedure, gas, grenades, collapse the entrance, move on.

But Richi had noticed something. The entrances were too close together. maybe 200 yards apart. That meant they were connected. That meant there was a network down there, not just individual fighting positions. And if there was a network, that meant command posts, supply caches, maybe even hospitals, things division wanted to know about, things worth taking risks for.

He waited until 2:00 a.m. Most of the company was asleep. The perimeter guards were focused outward, watching the treeine for enemy movement. No one was paying attention to the collapsed tunnel entrance 20 yards behind the command post. Richi grabbed his pistol, a flashlight, and a coil of camo wire from the supply tent.

He didn’t ask permission. He didn’t tell anyone where he was going. He just moved out into the darkness and started digging. The Vietkong had built the entrance to collapse easily and rebuild quickly. 10 minutes of work with an entrenching tool exposed the opening, maybe 2 ft wide, 3 ft tall, just big enough to crawl through.

He tied one end of the camo wire to a tree route, then wrapped the other end around his wrist. If he got lost, he could follow the wire back out. simple navigation, the same principle as laying string in the warehouse basement when the lights went out. He clicked the flashlight on, took three deep breaths and crawled into the earth.

The tunnel sloped down at a 15° angle for about 10 ft, then leveled off. The walls were hard packed clay, reinforced with bamboo in places. The ceiling was barely 3 ft high. Reachi had to move on his stomach, pushing the flashlight ahead of him, dragging himself forward with his elbows.

The air was thick and hot, heavy with the smell of dirt and decay. Every few yards he’d stop and listen. Nothing, just his own breathing and the sound of his uniform scraping against clay. 20 ft in, the tunnel turned sharply to the left. standard Vietkong construction to dissipate blast waves from grenades. Richi paused at the turn, shining his light around the corner before committing.

The tunnel continued, level and empty. He kept moving 30 ft 40. The camo wire played out behind him, a thin lifeline to the surface. He passed a side passage barely 2 feet wide that branched off to the right. He noted it mentally, but kept going straight. At 50 ft, he found the first chamber. The tunnel opened into a room about 6 ft across and 5 ft high, tall enough to crouch in, wide enough for three men to sit comfortably.

There were sleeping mats on the floor, a ceramic jug of water, a bamboo container that held rice and dried fish, evidence of recent occupation, maybe hours ago. maybe minutes. Richie’s heart hammered against his ribs. Someone had been here. Someone might still be here. He swept the flashlight across every surface, checking for trip wires, for weapons, for any sign of immediate danger.

Nothing obvious, but tunnel rats, who’d survived longer than a week, all said the same thing. The traps you don’t see are the ones that kill you. He backed out of the chamber slowly, every movement careful and deliberate. The tunnel continued past the chamber, sloping down again. Reachi followed it, paying out more wire, descending deeper into the network.

The air was getting worse. Less oxygen, more carbon dioxide. His head started to pound. At 70 ft, he found the second chamber. This one was larger, maybe 10 ft across, and it wasn’t empty. Two Vietkong soldiers were sitting against the far wall, AK-47s across their laps, apparently asleep. Reachi froze.

His flashlight was pointed directly at them. They hadn’t moved. They hadn’t raised their weapons. They were either incredibly heavy sleepers or something was very wrong. He studied them for 30 seconds. No movement, no breathing. He crawled closer, pistol raised. At 5 ft, he understood. They were dead. Both shot in the chest recently.

The blood on their uniforms was still tacky. Someone had killed them, probably within the past few hours, and left them here. Why? Reachi swept the flashlight across the rest of the chamber. The walls were lined with ammunition crates, Soviet 7.6 dual mm rounds for AK-47s, Chinese stick grenades, Bangalore torpedoes, enough explosives to level a city block, and in the far corner, partially hidden behind the crates, another tunnel entrance.

This one dropped straight down, maybe 10 ft, into darkness. The flashlight couldn’t penetrate. Reachi understood what he was looking at. This wasn’t just a fighting position. This was a supply depot, a way station on a larger network. The dead soldiers had probably been guards. Someone had killed them and gone deeper into whatever lay below.

He should have turned back. He’d found valuable intelligence. He’d proven the tunnels were connected. He’d mapped almost 80 ft of passageway. That was enough. That was more than enough. But the wire was still playing out, and the tunnel kept going, and some part of him needed to know what was down there. He checked his pistol.

Seven rounds. Seven chances to make it back alive. Who lowered himself into the vertical shaft, bracing his back against one wall and his feet against the other, shinning down slowly into the dark. The shaft descended 12 ft before opening into another horizontal tunnel. This one was different, wider, better constructed.

The ceiling was reinforced with wooden beams, the walls smooth and even. This wasn’t a crude fighting position dug in weeks. This was infrastructure built over months, maybe years. Reachi landed at the bottom and paused, listening. Still nothing. just silence and darkness and the sound of his own fear. He checked the wire. He’d used almost all of it, maybe 20 ft left.

He could go a little farther, just a little. The tunnel ran straight for 30 ft, then opened into a chamber unlike anything he’d seen before. This one was massive, maybe 20 ft across and 8 ft high. Tall enough to stand in, wide enough for a platoon. The walls were lined with benches. There were maps on the walls marked in Vietnamese.

radio equipment in one corner, American probably captured, a typewriter on a wooden table, stacks of documents in metal boxes, and in the center of the room, a table with six chairs, a command post. Reachi had found a Vietkong command post. He stood there for 10 seconds trying to process what he was seeing. This was the target.

This was what Division needed to know existed. This was proof that the tunnel networks weren’t just hiding places. They were operational bases, fully functional military installations that let the Vietkong operate beneath American positions with impunity. He needed to get out, needed to report this, needed to bring people back here with proper equipment and support.

He turned toward the tunnel entrance. That’s when he heard the voices. Vietnamese, multiple speakers coming from a passage on the opposite side of the chamber. Coming closer, Richi killed the flashlight. Darkness swallowed him, complete and absolute. He couldn’t see his hand in front of his face, couldn’t see the way out, couldn’t see anything except the faint glow of lamplight starting to appear from the far passage.

They were coming. He dropped to a crouch and moved toward the tunnel he’d entered from, feeling his way along the wall. His boot hit something metal, a canteen. It clattered across the floor. The voices stopped. Silence, then shouting. The glow got brighter. They were running now. Richi found the tunnel entrance and threw himself into it, crawling as fast as he could move, the flashlight off, navigating by memory and touch.

Behind him, more shouting. Flashlight beams swept the command chamber. Someone fired. The muzzle flash lit up the tunnel like lightning, and Richi saw the way ahead for half a second before darkness returned. He kept moving hand over hand, elbows and knees. The camo wire cut into his wrist. 20 ft 30. His head cracked against a support beam and stars exploded across his vision.

He kept moving the vertical shaft. He had to be close to the vertical shaft. His hand found empty air. The shaft. He grabbed the wire and pulled himself up, bracing against the walls, climbing hand overhand. Below him, flashlight beams entered the tunnel. Someone was following. Someone was close. Reachi reached the top of the shaft and rolled into the upper tunnel, gasping, his lungs burning.

Behind him, voices, ladder rungs hitting the shaft walls. They were climbing after him. He crawled fast as he could, following the wire back toward the entrance. 60 ft. 50. The air got fresher. He could smell the jungle. 40 ft. 30. A burst of automatic fire from behind. Rounds snapped past his head and chewed into the clay walls.

He didn’t return fire. Seven rounds wouldn’t stop what was chasing him, and muzzle flash would tell them exactly where he was. He crawled. The tunnel turned left. The turn that meant the entrance was 20 ft away. 15 ft. 10. He could see dim light ahead. Dawn light filtering down through the entrance. 5T. Richi exploded out of the tunnel entrance like a man drowning who’d finally found surface.

He gulped air, rolled to his feet, and ran toward the perimeter, still clutching the wire. Behind him, someone emerged from the tunnel. Reachi heard the distinctive crack of an AK-47. Rounds snapped through the air around him. He hit the ground behind a fallen log as the camp exploded into action. Soldiers grabbed weapons.

Someone opened fire on the tunnel entrance. A grenade detonated underground with a muffled wump. Captain Thornton appeared, rifle in hand, demanding to know what the hell was happening. Reachi, still gasping, told him. Told him everything. The chambers, the supplies, the command post, the documents, the Vietkong who’ chased him to the surface.

Thornton’s expression cycled through fury, disbelief, and something that might have been respect. You went into that tunnel alone? Yes, sir. Without authorization? Yes, sir. You found a command post? Yes, sir. Show me. By 9:30 a.m., Thornton had assembled a squad, not to punish Reichi, but to exploit what he’d found.

They cleared the tunnel with grenades, smoke, and overwhelming firepower. The Vietkong who chased Reichi had retreated deeper into the network, but the command post was still intact. What they found changed everything. The documents included maps of American positions, plans for attacks on Li base camp, supply routes from Cambodia, lists of local sympathizers, communication codes, everything division intelligence had been trying to piece together for months, all in one place.

One officer would later call it the single most valuable intelligence find of the war to that point. But the cost was immediate. The Vietkong knew the command post had been compromised. Within hours, they’d collapsed multiple tunnel entrances and moved operations. And they’d learned that Americans were now going into the tunnels.

That changed their tactics. If Americans could come underground, then the tunnels weren’t safe anymore, which meant the Vietkong would defend them more aggressively. Three days later on January 14th, 1966, Corporal Robert Bautell of the Australian Third Field Troop entered a tunnel during a clearing operation. He found a Vietkong fighter waiting in a side chamber.

Close quarters gunfight in absolute darkness. Bottel fired six rounds, hit three times. So did the Vietkong fighter. Bell crawled 20 ft back toward the entrance before he bled out. The tunnel collapsed shortly after his squad pulled his body out. The Vietkong fighter’s body was never recovered. Botel was 24. He’d volunteered for tunnel duty.

His death wasn’t in vain, but it was direct. His loss gutted the Australian engineers. 4 days later, Private First Class William Lightfoot of the First Infantry Division entered a tunnel near Ben Souk Village. He found a spider hole that led to a lower level. He dropped down. A Vietkong fighter was waiting below, hidden in a side chamber no larger than a closet.

Lightfoot never had a chance to raise his weapon. Shot twice at point blank range. dead before his squad even knew he was in trouble. The Vietkong escaped through a passage Lightfoot never saw. Specialist James Moore died on January 19th. Same pattern. Tunnel entrance, descent into darkness, ambush from a concealed position.

Moore fought back, killed his attacker, but took a round through the lung. His squad pulled him out. He died on the medevac helicopter. On January 21st, Sergeant Ronald Payne went into a tunnel in the Hobo Woods with a suppressed revolver and a knife. He survived, but barely. Vietkong fighter in a side chamber. Firefight at 3 ft.

Pain killed him but took shrapnel from a grenade. Two fingers lost her and damaged permanently. He went into 17 more tunnels after that. By January 26th, when Operation Crimp officially ended, 11 men had died in tunnel related incidents. Another 23 had been wounded. The official casualty report attributed the deaths to enemy action during search operations.

It didn’t specify that every single one had occurred underground in spaces where American firepower meant nothing and training was irrelevant. The statistics told a story. command didn’t want to acknowledge. In the three weeks of Operation Crimp, tunnel operations resulted in the discovery of 10 major command posts, enough weapons to supply three battalions, and intelligence that included half a million pages of documents, critical stuff, war intelligence.

But the cost per discovery was more than one American life. Nobody said that out loud, but everyone knew it. The tunnel networks weren’t just military installations. They were killing grounds. Captain Thornton didn’t punish Reachi. Instead, he made him an instructor. If soldiers were going to go into tunnels, they needed training that didn’t exist.

Reachi spent February 1966 teaching volunteers what he’d learned. Never use a flashlight that the Vietkong could see from a distance. Red lens only and only when absolutely necessary. Never fire more than three shots before reloading. Vietkong would rush you during reload. Listen for air flow. It tells you about chamber size and other entrances. Mark your path.

Wire, chalk, anything. You get lost down there, you die. Check every surface before you touch it. Trip wires are invisible in the dark. The volunteers were almost all small men. Height and weight restrictions became unofficial requirements. You had to fit through openings designed for Vietnamese fighters who averaged 5’4 and 120 lb.

You had to be comfortable in the dark. You had to volunteer because no one could be ordered to do this. They called themselves tunnel rats. The name stuck. By March 1966, the first infantry division had two tunnel rat teams, eight men total. By June, the number had grown to 15.

Other divisions started creating their own teams. The Australians who’d lost Bowel refined the techniques, used compasses underground, ran phone lines behind them for communication, mapped every tunnel before collapsing it. Americans took a different approach. Find it, clear it, destroy it, move on. Both methods worked. Both cost lives. The Vietkong adapted faster than anyone expected.

They built false tunnels that led to dead ends lined with pungi stakes. They placed grenades on trip wires at head height. They trained fighters specifically to kill tunnel rats. Close quarters combat in absolute darkness. Knife work, silent kills, the kind of fighting that left no survivors to describe what had happened. Some tunnel rats never came back.

Some came back different. Shell shocked wasn’t the right term. They’d seen things in the dark that nobody who hadn’t been there could understand. Private Daniel Foster went into a tunnel in May 1966. Found a chamber full of Vietkong soldiers who’d been killed by CS gas days earlier. 23 bodies left to rot because nobody could retrieve them.

The smell was so bad, Foster vomited inside his gas mask and nearly suffocated. He cleared five more tunnels after that, then refused to go into a sixth. Nobody blamed him. Specialist Carl Corey went into a tunnel in July 1966. Found a Vietkong fighter sitting in a side chamber, weapon in his lap, apparently sleeping.

Cory approached carefully, shined his light. The fighter was dead. Had been for days, but he’d been positioned to look alive. Rifle arranged across his knees, head tilted back against the wall. Psychological warfare. Make the tunnel rat hesitate. In that hesitation, someone else could kill him.

Cory cleared the rest of the tunnel, found nothing else. But he never forgot that dead man arranged like a trap. The tunnel networks themselves grew more sophisticated. By late 1966, some extended for miles, multiple levels, blast doors between sections, ventilation systems that could expel gas, underground hospitals with surgery tables, training areas, printing presses, even some living quarters with kitchens.

The Vietkong had built cities beneath the jungle, entirely functional military bases that let them operate in areas where Americans maintained constant presence on the surface. The Coochi tunnels were the most extensive. 250 kilometers of interconnected passages from the outskirts of Saigon to the Cambodian border. The 25th Infantry Division built their base camp at Kuchia, directly on top of one of the largest tunnel complexes in South Vietnam.

For months, American soldiers lived, ate, and slept while Vietkong fighters moved freely beneath their feet. Mortar attacks that seemed to come from nowhere. Sniper fire from impossible angles. ambushes that materialized from empty ground. All because the enemy was literally underground. Operation Cedar Falls in January 1967 was supposed to change that.

30,000 troops, the largest American operation of the war so far. Objective: clear the Iron Triangle and destroy the tunnel networks once and for all. The operation killed approximately 750 Vietkong and captured 280. It uncovered massive tunnel complexes, seized tons of supplies, captured intelligence that filled warehouses, but it didn’t destroy the tunnels.

B-52 strikes carved craters 50 ft deep. Rome plows cleared vegetation. Engineers pumped acetylene gas and explosives into every entrance they found. Some sections collapsed, some were abandoned, but within months, the Vietkong had rebuilt what was destroyed and expanded into new areas. The tunnels were like living organisms. Cut one section, it regenerated.

Destroy one entrance, three more appeared. The cost to Americans was 72 killed and 337 wounded. 11 of those deaths occurred underground during tunnel clearing operations. 11 more tunnel rats who went into the dark and didn’t come back. Michael Reichi cleared 47 tunnels between January 1966 and September 1967. He was wounded twice.

Shot once in the shoulder during a firefight in a tunnel near Tay Nin. Took shrapnel from a booby trap in a tunnel near Pu Kuang. Both times he was back underground within weeks. He trained over 60 soldiers in tunnel warfare. Wrote unofficial guidelines that became the basis for actual doctrine. Helped design equipment that worked better than what supply issued.

Red lens flashlights, suppressed revolvers, better knives, communication equipment that functioned underground. Captain Thornton put him in for a bronze star in June 1967. Division approved it in August. Reachi received the medal in a ceremony at Lay. The citation mentioned leadership and technical expertise. It didn’t mention the 47 tunnels or the times he should have died but didn’t.

He rotated home in December 1967, 2 years and 3 months after arriving in Vietnam. No fanfare, no parade. Just orders and a plane ticket and a promise that the war would be over soon. The war wasn’t over soon. It lasted eight more years. The tunnel networks remained operational until the fall of Saigon in 1975. Over the course of the war, approximately 100 American soldiers served as tunnel rats.

Most were wounded at least once. Many died. The exact number is disputed because tunnel rat wasn’t an official MOS and deaths were recorded as combat casualties without specifying the circumstances. Conservative estimates suggest 40 to 60 tunnel rats were killed in action. Many more were wounded so severely they couldn’t continue.

Psychological casualties were higher. Men who came back from the tunnels but left something essential behind in the dark. The Vietkong paid a higher price. At least 45,000 Vietnamese fighters died defending the Coochi tunnels alone. Thousands more died in other tunnel complexes across South Vietnam, but they achieved their objective.

The tunnels allowed them to survive, to operate, to maintain military pressure despite overwhelming American firepower. The tunnels proved that technology couldn’t solve every problem. That sometimes the simplest solution was the hardest to defeat. that will and ingenuity could overcome almost any advantage. After the war, the Vietnamese government preserved portions of the Coochi tunnels as a memorial.

They widened them for tourists, added lighting, made them safe. The original tunnels were barely 2 ft wide in places dark as death, hot as an oven. Crawling through them was like crawling through your own grave. Americans who went into those tunnels and came out alive were a special breed. Not brave necessarily. Brave implied they had a choice.

Most of them went because someone had to because if they didn’t, more soldiers would die not knowing what was beneath their feet. Because intelligence won wars. And the best intelligence was firsthand. The tunnel rats weren’t in the history books much. weren’t celebrated. Most never talked about what they’d done.

What do you say? I crawled through hell. I fought invisible enemies. I lived in the dark for months. None of that sounds real when you say it out loud. Michael Reachi never talked about Vietnam. He went back to Philadelphia, got his job back at the warehouse, married a woman named Angela, who worked at a bakery two blocks from his father’s grocery.

They had two kids. He worked 41 years in supply chain management, mostly the same job he’d been doing before the war, moving boxes, maximizing space, making sure inventory went where it needed to go. He never told his kids he’d been a tunnel rat. Never mentioned the Bronze Star. Threw away his uniform in 1970 because looking at it made him remember things he didn’t want to remember.

Once a year on January 11th, he received phone calls, other tunnel rats, men who’d survived the same darkness. They’d talk for a few minutes, remember names. Kowalsski, Bautel, Lightfoot, more. The list grew longer every year as age and Agent Orange and everything else took its toll.

In 1989, a military historian researching tunnel warfare tracked him down through army records, asked for an interview. Reachi agreed to meet once, explained how the tunnel operations had worked, described the techniques, provided dates and unit designations, then asked that his name not be used in the publication.

The historian respected that request. The book published in 1991 attributed tunnel rat innovations to unidentified specialists in the first infantry division. Michael Reachi died in 2003 at age 59, heart attack at the warehouse. His obituary in the Philadelphia Inquirer mentioned that he was a Vietnam veteran and longtime warehouse manager.

It didn’t mention tunnels, command posts, or the 47 times he’d crawled into darkness, not knowing if he’d come back. Angela knew he’d done something important in Vietnam, but never knew exactly what. The method itself outlived the men who perfected it. Modern military forces still train soldiers for tunnel operations.

ISIS tunnel networks in Iraq and Syria required American troops to use techniques developed in Vietnam. Hamas tunnel systems in Gaza, Mexican cartel tunnels. Wherever people dig underground to hide or fight, someone has to go in after them. The principle hasn’t changed. Sometimes the only way to understand a threat is to face it directly, to go where the enemy feels safe and prove they’re not.

The tunnel rats prove that courage isn’t always loud. Sometimes it’s quiet. Sometimes it’s crawling through absolute darkness with a pistol and a prayer, knowing that every inch forward might be your last. Sometimes it’s volunteers doing a job nobody wants because it needs doing. The tunnels are still there beneath the Vietnamese jungle.

Miles of passageways, chambers, fighting positions. Most have collapsed. Some remain intact. They’re part of the landscape now. Part of history. Evidence of a war fought above and below ground. Evidence of soldiers who descended into hell and tried to map it so others wouldn’t have to. That’s how real innovation happens in war.

Not through PowerPoint presentations and white papers. Through corporals who can’t watch their friends die anymore. Through warehouse managers who understand spaces better than the people who designed them. Through volunteers who risk everything to solve problems nobody else can solve. The tunnel rat method was officially adopted into army doctrine in 1969.

By then, hundreds of soldiers had already been doing it for years, dying for it, perfecting it. The manual codified what they’d learned in blood, made it official, gave it structure. But the men who’d figured it out in the dark never needed a manual. They just needed courage and a reason to keep going. The reason was simple.

If not them, then who? If they didn’t go into those tunnels, someone else would have to, someone less experienced, someone who might not come back. So they went, mission after mission, tunnel after tunnel until they rotated home or died or couldn’t do it anymore. Sometimes that’s enough. Sometimes soldiers don’t need medals or recognition.

They just need to know the job got done. That their friends didn’t die for nothing. That the intelligence they gathered saved lives even if nobody remembers their names. The wire Reachi used on that first tunnel operation is in a museum now. Part of a collection of Vietnam War artifacts. There’s no plaque with his name.

Just a coil of communication wire with a card that reads used by tunnel rats of the first infantry division Vietnam 1966. Sometimes that’s exactly right. If you found this story compelling, please like this video. Subscribe to stay connected with these unheard histories. Leave a comment telling us where you’re watching from.

Thank you for keeping these stories alive.