They called them Maang, the jungle phantoms. And if you were a Vietkong fighter in Puaktui province, those two words were the last thing you wanted to hear. But here’s what the history books won’t tell you. Here’s what the Pentagon classified for decades. Here’s what American soldiers whispered about in hushed voices, afraid that speaking too loudly might summon something from the darkness.

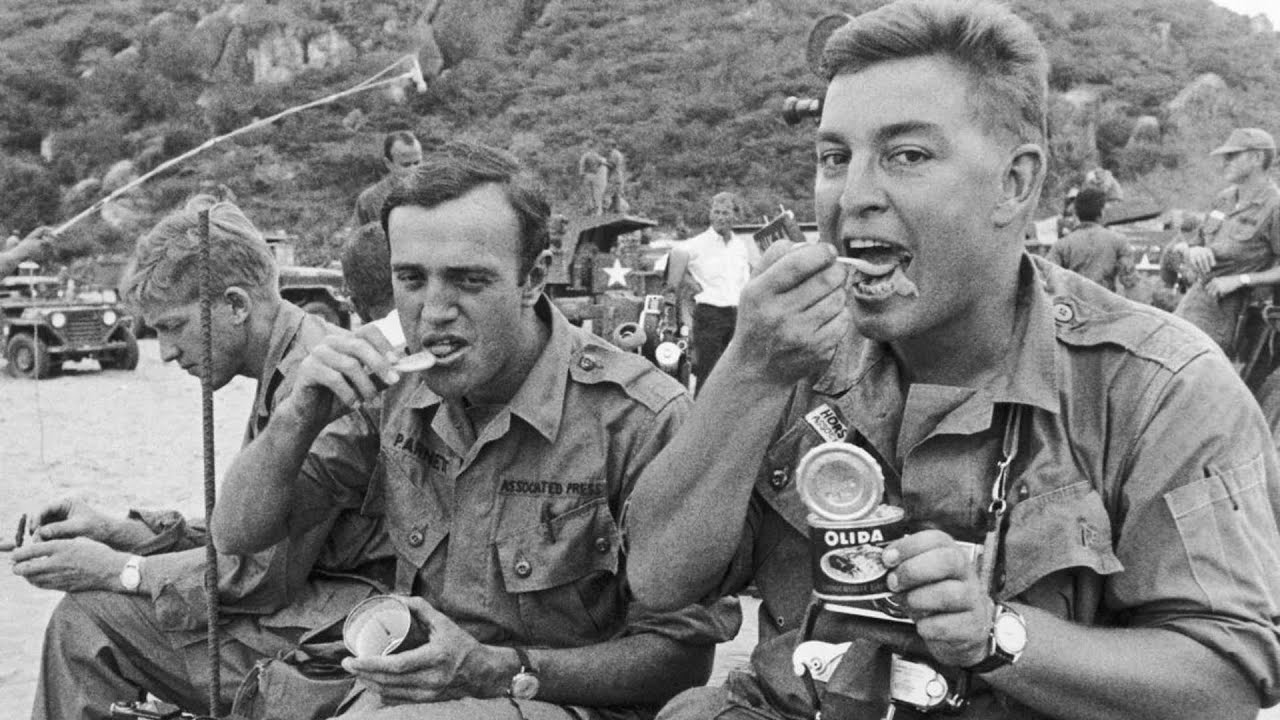

The Australians, the SAS, they did things in that jungle that made hardened green berets turn pale. They used methods so terrifying, so psychologically devastating that American commanders ordered their own men to stay away from Australian base camps. And the rumor that spread fastest, the one that kept US Army personnel awake at night.

They said the Australians ate the hearts of their enemies, raw, still warm. Was it true? Was it propaganda? Or was it something far more calculated? A psychological weapon so effective that it’s still classified to this day. I’ve dug into declassified reports. I’ve found accounts from American veterans who were there.

I’ve uncovered details that the Australian Defense Force has never officially acknowledged. What really happened at Nui Dat? What did that American helicopter crew witness that made one of them vomit on the spot? And why did the Pentagon bury their own investigation into Australian methods? Stay with me until the end because what I’m about to reveal will change everything you thought you knew about the Vietnam War and about the most feared soldiers who ever fought in it.

This is the story they didn’t want you to hear. Let’s begin. The American sergeant stopped dead in his tracks. His boots sank into the red mud of Fuaktoy province, but he could not move another inch forward. ahead of him. Through the razor wire and sandbag perimeter of the Australian base at Nui Dat, he saw something that would haunt his dreams for the next 50 years.

A group of sunblocked men sat in a loose circle, sharpening knives that curved like the fangs of some jungle predator. Their eyes tracked him with the cold patience of crocodiles watching prey approach the waterline. One of them smiled. It was not a friendly smile. The sergeant turned around and walked back to his jeep.

He would file his report from a safer distance. He would recommend that American personnel avoid unnecessary contact with the Australian Special Air Service Regiment. And he would never ever speak of what he thought he saw hanging from the tent pole behind those men. This was new. He died in 1967. This was the home of the most feared soldiers in Southeast Asia.

But the nightmare was only beginning. The whispers started almost immediately after the first Australian SAS patrols slipped into the jungle. American advisers stationed throughout South Vietnam began hearing strange reports from their Vietnamese counterparts. The Vietkong, those hardened guerilla fighters who had humiliated French colonizers and were grinding down the American war machine, had developed a new fear.

They called the Australians quote one, the phantoms of the jungle. They said these pale skinned devils moved through the bush without making a sound. They said these men could track a single footprint across kilometers of Triple Canopy Forest. They said these warriors did things to captured enemies that made even the most battleh hardened VC commasar lose sleep.

But the most persistent rumor, the one that spread through American fire bases like wildfire through dry elephant grass, was far more disturbing. They said the Australians ate the hearts of their enemies, raw, still warm. They said it was a ritual, a blood ceremony that transformed ordinary soldiers into something else entirely.

Something that belonged more to nightmare than to any military organization bound by the Geneva Conventions. Was it true? The official answer was always no. Absolutely not. Categorically denied. But the unofficial answer painted a very different picture. To understand how these rumors began, one must first understand what made the Australian SAS fundamentally different from every other special operations unit in Vietnam.

The Americans had their green berets, their Navy Seals, their MAC Visog operators running crossber operations into Laos and Cambodia. These were elite warriors. No question. They were brave, skilled, and dedicated. But they operated according to American military doctrine, which in 1966 meant one thing above all else, firepower.

The American way of war was simple. Find the enemy, fix him in place, destroy him with overwhelming force, call in the artillery, call in the air strikes, call in the B-52s if necessary, reduce the jungle to splinters and ash, then count the bodies, and report the numbers to Saigon.

The Australians looked at this doctrine and saw madness. and what they did instead would shock the entire American military establishment. Their approach came from a completely different tradition. The Australian SAS had been forged in the jungles of Malaya during the 12-year emergency, hunting communist guerillas through terrain that made Vietnam look like a city park.

They had learned their craft from British SAS veterans who had perfected small unit tactics against insurgents in Burma, Kenya, and Borneo. And crucially, they had incorporated techniques from Aboriginal trackers whose ancestors had been reading the Australian bush for 40,000 years. Where Americans saw the jungle as an obstacle to be destroyed, Australians saw it as an ally to be embraced.

Where Americans announced their presence with helicopter insertions and artillery preparations, Australians slipped into the green like ghosts dissolving into mist. where Americans measured success in body counts reported to eager Pentagon analysts, Australians measured success in intelligence gathered, movements disrupted, and terror planted deep in enemy hearts.

The first clash between these two philosophies came in the early months of 1966, and it set the tone for everything that followed. Captain James Sullivan of the United States Army Special Forces was not a man who impressed easily. He had survived two tours with the Green Beretss, including a particularly nasty stretch advising Montineyard tribesmen in the central highlands.

He had seen things that would break ordinary men. He had done things that he would never discuss, not even with his wife, not even on his deathbed decades later. So when his commanders ordered him to serve as a liaison officer with the newly arrived Australian task force at Nuidot, he approached the assignment with professional confidence.

That confidence lasted exactly 72 hours. On his third day at the Australian base, Sullivan requested permission to accompany an SAS patrol into the jungle. The Australian squadron commander, a lean and weathered major with eyes the color of faded khaki, studied the American for a long moment before responding.

The answer was, “No, not yet. First, the American would need to unlearn everything he thought he knew about jungle warfare.” The major’s next words hit Sullivan like a punch to the gut. First, he would need to prove he could move through the bush without announcing his presence to every enemy within a kilometer.

First, he would need to understand that out there in the green, noise meant termination, and smell meant termination, and even thinking too loudly could get an entire patrol wiped out. Sullivan bristled at this. He was a green beret for God’s sake. He had trained at Fort Bragg. He had completed the jungle warfare course in Panama. He knew what he was doing.

The Australian major smiled that same unsettling smile the sergeant had seen through the wire. Then he issued a challenge. Sullivan would spend one week training with the SAS. At the end of that week, if he could pass their patrol readiness test, he would be welcome to accompany them into the jungle. If he failed, he would return to his American unit and file whatever report he wished.

Sullivan accepted immediately. He was certain he would pass. He was certain he would show these Australians that American special forces were every bit their equal. He was wrong. Completely, utterly, devastatingly wrong. The training began before dawn the next morning, and it bore no resemblance to anything Sullivan had experienced in the American military.

There were no obstacle courses, no timed runs, no classroom lectures on small unit tactics. Instead, an Aboriginal tracker named Wilson. Just Wilson. No rank, no surname offered. Led Sullivan into a patch of jungle at the edge of the base perimeter. For the first 3 hours, they simply sat. Wilson said nothing. He did not explain what they were doing or why.

He simply sat with his back against a rubber tree and watched the jungle with the patience of a man who had nowhere else to be for the rest of eternity. Sullivan fidgeted. He checked his watch. He swatted at mosquitoes. He opened his mouth to ask questions. at least a dozen times, but something in Wilson’s absolute stillness made him close it again.

Finally, as the sun climbed toward its noon apex, Wilson spoke, and what he said changed everything Sullivan thought he knew about warfare. He asked Sullivan what he had heard during those three hours. Sullivan reported the obvious, birds, insects, the distant thump of artillery, a helicopter passing overhead. Wilson shook his head slowly.

Wrong answer. He had heard 17 distinct bird calls, each one indicating a different state of jungle alertness. He had heard the movement of a small mammal approximately 40 m to the east. He had heard the breathing of at least two other humans, Australians, on a training exercise, who had passed within 15 m of their position without Sullivan detecting them.

And most importantly, Wilson continued, he had heard Sullivan’s heartbeat. The American’s pulse had been elevated throughout the entire exercise, pumping adrenaline through his system, keeping his senses sharp, but his awareness shallow. A man with a racing heart could not truly listen. A man with a racing heart could not become part of the jungle.

A man with a racing heart would be detected and eliminated before he ever knew the enemy was there. Sullivan wanted to argue. He wanted to point out that his heartbeat was not audible to the naked ear, that this was mystical nonsense. But deep down, in that place where soldiers learned to trust their instincts over their training, he knew Wilson was right.

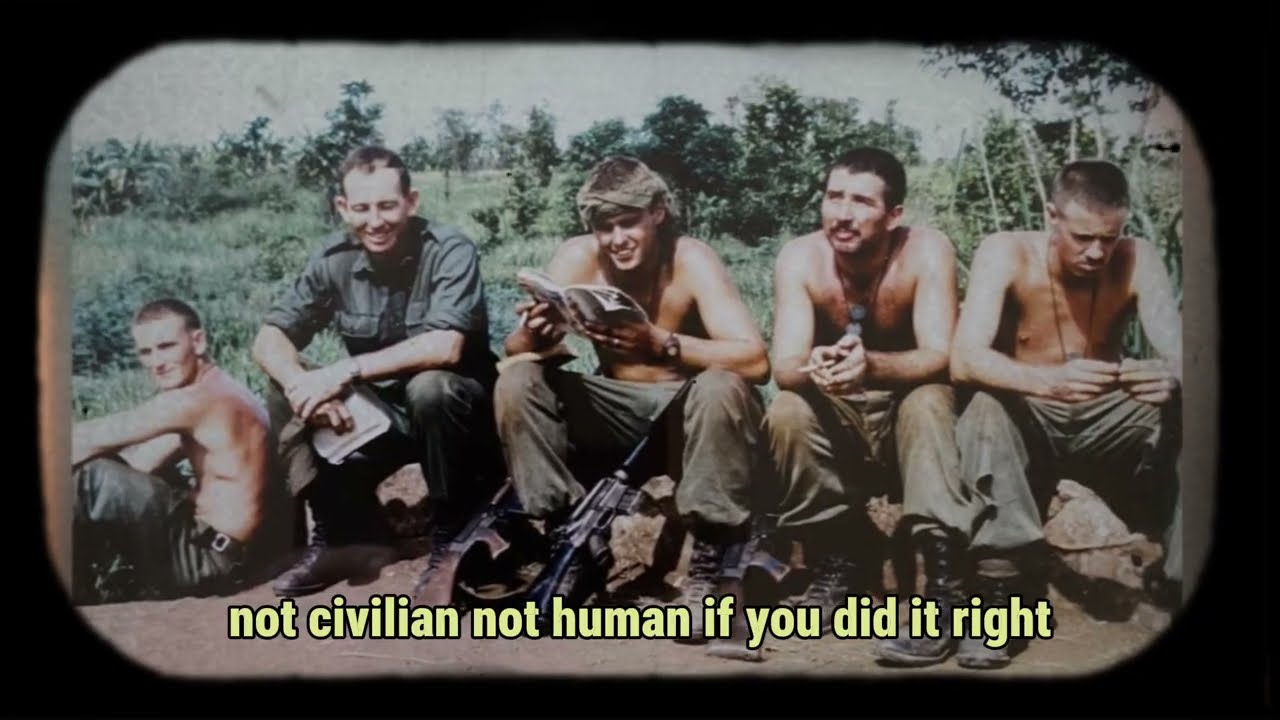

The next six days nearly destroyed him. The Australians trained differently because they thought differently. For them, a patrol was not a military operation in the conventional sense. It was a hunt. And in any hunt, the predator who made noise, who left traces, who announced his presence became the prey. Sullivan learned to walk on the edges of his boots, rolling each step from heel to toe in a motion that distributed his weight without snapping twigs or rustling leaves.

He learned to control his breathing, slowing his respiration to match the rhythm of the jungle around him. He learned to eat cold rations without heating them because the smell of cooking food could travel hundreds of meters through the humid air. He learned to defecate into plastic bags and carry his waste with him rather than leave any trace of human presence.

But the most disturbing lesson came on the fourth day. He observed an SAS patrol preparing for a mission. The men moved through their pre-operation routine with the silent efficiency of monks performing an ancient ritual. They applied camouflage paint and patterns that broke up the human silhouette rather than simply darkening the skin.

They removed every piece of metal that might clink or reflect light. They taped down every buckle, every zipper, every potential noise source. They checked each other’s equipment with an intimacy that seemed almost inappropriate, hands moving over bodies with clinical precision. Then one of them pulled out a knife and began modifying his boots.

Sullivan watched in confusion as the soldier carefully cut away portions of the soul, removing the distinctive tread pattern that would leave identifiable tracks. When he asked why, the soldier looked at him with something between pity and contempt. The Vietkong knew American bootprints, he explained. They could identify a US patrol from a single footprint and know exactly how many men had passed, how long ago, and in what direction they were traveling.

The cut boots left prints that looked like nothing. Not military, not civilian, not human if you did it right. It was such a simple innovation, and it had never occurred to anyone in the entire American military establishment. Sullivan began to understand why the Australians looked at their US allies with such barely concealed disdain.

But the boots were just the beginning. The real shock came when he learned about the bodies. The official records of Australian SAS operations in Vietnam are remarkably sparse. The Australian War Memorial in Canra contains patrol reports, afteraction summaries, and casualty lists. What it does not contain, what has never been officially acknowledged are the psychological operations that made the SAS so terrifyingly effective.

The whispers among American forces spoke of body displays. Vietkong fighters found arranged in poses of horror. Their corpses manipulated to send messages to those who discovered them. The whispers spoke of trophy collecting, of items taken from enemy remains that served purposes beyond intelligence gathering.

The whispers spoke of methods that crossed lines Americans were not supposed to cross, lines that existed in training manuals and Geneva Convention briefings, but seemed to dissolve in the green hell of the jungle. How much of this was true? The veterans who served with the Australian SAS during this period have maintained a remarkable silence for over half a century.

Some have gone to their graves without speaking. Others have offered carefully worded non-denials that neither confirm nor contradict the rumors. A few late in life have let slip details that suggest the whispers barely scratch the surface. One American intelligence officer interviewed decades later under condition of anonymity described a briefing he received in Saigon during the summer of 1967.

His superiors wanted to know why Australian SAS kill ratios were so dramatically higher than comparable American units. They wanted to understand the methods. They wanted to determine whether those methods could be adopted by US forces. The officer spent three weeks investigating. He interviewed American personnel who had worked alongside the Australians.

He reviewed captured enemy documents that referenced underscore quote un_2 operations. He even managed to debrief a Vietkong defector who had survived an encounter with an Australian patrol. His final report was classified immediately upon submission. The classification level was higher than anything he had previously encountered.

His superiors thanked him for his work and strongly suggested that he never speak of it again. When he asked why the methods could not be adopted, he was told that some techniques were simply not compatible with American values. When he pressed for clarification, he was reminded that his career depended on his discretion.

40 years later, sitting in a retirement community in Arizona, he would say only this quote three quote four. The heart eating rumor specifically appears to have originated from a single incident in late 1966, though the details have been obscured by time, official suppression, and the fog of war. According to accounts that have filtered through various unofficial channels, an American helicopter crew made an unscheduled landing near an Australian patrol base deep in Puaktoy province.

They were experiencing mechanical difficulties and needed to set down immediately. What they found when they emerged from their aircraft would circulate through American units for years afterward. A group of Australian SAS operators had just returned from a patrol. They were gathered around something in the center of their camp.

The helicopter crew approached, curious about what had drawn such intense focus. What they saw made one of them vomit immediately. Another turned and ran back to the aircraft. The third, the pilot, stood frozen as an Australian casually looked up at him and asked if they needed assistance. The official report filed by the helicopter crew was vague to the point of uselessness.

Mechanical malfunction, emergency landing, brief contact with Allied forces, successful repair and departure. No details about what they witnessed. No explanation for the psychological evaluation one crew member required upon returning to base. No mention of the incident that gave birth to the most persistent rumor of the entire war.

Did the Australians actually consume human organs? Almost certainly not. The logistics alone would make such a practice impractical, and no credible evidence has ever emerged to support the literal interpretation of the rumor. But something happened at that camp that day, something that American eyes were never meant to see. The most likely explanation offered by historians who have studied the incident involves the psychological operations the SAS conducted against enemy morale.

The Vietkong believed deeply in the spiritual significance of bodily integrity after passing. They feared that mutilation would condemn their souls to eternal suffering. The Australians who had learned similar techniques from British SAS veterans of the Malayan emergency understood how to exploit this fear.

What the helicopter crew probably witnessed was not cannibalism, but theater. A carefully staged display designed to be witnessed by enemy eyes to be reported up the Vietkong chain of command to spread terror through whisper networks until every gerilla in Fuaktui province believed that the Australian phantoms were not merely human soldiers but demons who fed on their victims.

The fact that Americans witnessed it instead was an accident. But once the rumor entered the American information ecosystem, it took on a life of its own. And it served Australian purposes just as effectively as it would have served against the enemy. Because here was the truth that American commanders slowly began to realize.

The Australians did not want American help. They did not want American advisers, American firepower, American tactical support, or American presence anywhere near their operations. They had been given a province to pacify, and they intended to pacify it their way without interference from allies whose methods they considered not merely different, but actively counterproductive.

Every time an American unit operated in Fuaktoy province, the careful web of intelligence the Australians had built was disrupted. American patrols announced their presence with noise, with helicopter insertions, with artillery preparations that gave the enemy hours of warning. The rumors about Australian savagery served a dual purpose.

They terrified the enemy, yes, but they also kept Americans away. What commander would send his men to coordinate with allies who might be engaging in war crimes? What soldier would volunteer for a liazison position with units rumored to practice cannibalism? The more horrifying the stories became, the more autonomy the Australians enjoyed.

Several American officers who served in Vietnam have suggested in interviews conducted long after their retirements that the Australians deliberately cultivated their fearsome reputation specifically to maintain operational independence. The stories were not accidents or unwanted leaks. They were strategic communications planted through carefully managed channels designed to create exactly the result they achieved.

If this theory is correct, it represents one of the most successful psychological operations of the entire war. Directed not at the enemy, but at an ally. Captain Sullivan completed his week of training with the Australian SAS. He did not pass their patrol readiness test. The margin of his failure was not recorded in any official document, but the Australians apparently found his efforts sufficient to warrant a consolation prize.

He was allowed to accompany a patrol to their forward operating base, remaining behind while the combat team slipped into the jungle and observing the intelligence processing that occurred when they returned. What he saw during that observation period changed his understanding of the war. The Australian patrol had been out for 9 days.

9 days of moving through enemy territory without resupply, without fire support, without any of the safety nets American units considered essential. Nine days of sleeping in shifts while the jungle pressed in around them. Nine days of eating cold rations and drinking water from streams they treated with iodine tablets.

Nine days of absolute silence, communicating through hand signals and facial expressions, becoming something more than a military unit and something less than individual human beings. When they returned, they brought intelligence that would have taken American units months to gather. They had mapped enemy supply routes.

They had identified village chiefs who were secretly supporting the Vietkong. They had located a weapons cache that contained enough material to arm an entire battalion, and they had done all of this without firing a single shot. But it was what happened after the debriefing that Sullivan would remember most vividly. The patrol leader, a sergeant whose name has been redacted from every available record, asked Sullivan to join him for a drink.

They sat outside the intelligence tent as the tropical sun descended toward the horizon, sharing a bottle of Australian beer that had somehow remained cold in the jungle heat. The sergeant spoke quietly, almost conversationally, about what the past 9 days had been like. He described the moment on day three when they detected a VC patrol moving toward them and spent 6 hours motionless in a stream bed while the enemy passed within arms reach.

He described the night on day five when one of his men developed a fever and they had to decide whether to abort the mission or risk losing him in the jungle. He described the village on day seven where they watched through binoculars as a Vietkong political officer conducted a meeting, memorizing faces and names that would later be matched against intelligence databases.

And then he described what they had done on day eight when they found the body. The sergeant’s account, which Sullivan would later attempt to include in his official report before being ordered to remove it, went something like this. On the eighth day of the patrol, moving through an area they had identified as a likely enemy transit route, the Australians discovered the remains of a Vietnamese man in the undergrowth.

The body had been there for perhaps two days, judging by the state of decomposition. The cause of his demise was evident. multiple gunshot wounds to the torso, the signature of an American M16 rifle. The man wore the black pajamas of a Vietkong fighter, but his hands were soft, uncaloused, suggesting he had not spent his life working in the fields.

A political officer, most likely, someone important. What the Americans had done was standard practice. They had engaged an enemy contact, eliminated the threat, and continued their mission. What they had not done was exploit the opportunity. The Australians did not make the same mistake. Over the next 3 hours, working in total silence, the patrol transformed the scene.

They arranged the body in a position that would communicate specific meaning to any Vietkong who discovered it. They placed objects on and around the remains that would suggest particular methods had been employed. They created, in essence, a message written in flesh and fear. When they finished, the sergeant explained to Sullivan, “Any enemy who found that body would believe they were operating in territory controlled by demons.

They would report up their chain of command that the Maung had been there. They would request reassignment to other provinces. They would tell their comrades that Fui was cursed ground, haunted by spirits that fed on revolutionary fighters. And none of it would be true. No torture had occurred. No atrocity had been committed.

The man had already been beyond suffering when the Australians found him. All they had done was arrange the evidence to suggest things that had never happened. Sullivan asked if this was standard procedure. The sergeant finished his beer before answering. Sullivan’s report on Australian SAS methods was submitted to his commanding officer in Saigon 2 weeks later.

The relevant sections were immediately classified. He was transferred to a desk job in Japan within the month. He never served in Vietnam again. But the statistics tell a story that no classification stamp could hide. The statistical record of Australian SAS performance in Vietnam speaks for itself, even when stripped of the classified operational details.

During their deployment from 1966 to 1971, Australian SAS squadrons conducted approximately 1,200 patrols in Fuai Province and surrounding areas. They reported contact with enemy forces on roughly one-third of these missions. Their kill ratio, the number of enemy eliminated versus friendly casualties, has been estimated at anywhere from 500 to1 up to 1,000 to1 depending on which accounting methods are used.

Compare this to American special operations units during the same period. The Green Berets operating throughout South Vietnam reported kill ratios of approximately 20 to1. Navy Seals in the Mikong Delta achieved ratios of perhaps 50 to1. Even the legendary MAC Visog teams running classified missions into Laos and Cambodia rarely exceeded 100 to1.

The Australians were not merely better. They were operating on a completely different scale of effectiveness. American military analysts who studied these numbers were initially skeptical. They suspected the Australians were inflating their figures, as units throughout Vietnam routinely did under the pressure of the body count system, but when independent verification was attempted, the numbers held up.

In some cases, the actual results were even more impressive than the reported statistics. How was this possible? How could a force of fewer than 250 men at any given time achieve results that exceeded American units many times their size? The answer lay in the fundamental difference between hunting and fighting. American forces in Vietnam were configured for conventional warfare.

They were trained to close with the enemy and destroy him through superior firepower. Their doctrine assumed that contact with the enemy was desirable, that engagements were to be sought rather than avoided, that success meant maximum destruction of enemy personnel and material. The Australians rejected this approach entirely.

For them, a patrol that achieved contact was often a patrol that had failed. The ideal mission was one where intelligence was gathered, enemy movements were tracked, and ambushes were prepared without the enemy ever knowing they were being watched. When contact did occur, it was on Australian terms at a time and place of their choosing with every advantage stacked in their favor.

This required patience that American military culture could not accommodate. A typical SAS patrol would spend days moving into position, watching, waiting, gathering information that would shape future operations. They might pass up opportunities to engage enemy forces if the timing was not perfect. They might withdraw without firing a shot if the situation did not favor them.

They measured success not in bodies counted, but in intelligence gained and terror spread. The result was a form of warfare that the Vietkong had never encountered before. They were experienced in fighting Americans whose tactics were predictable and whose presence was always announced in advance. They knew how to disappear before the helicopters arrived, how to survive the artillery barges, how to wait out the search and destroy operations and return to their villages when the Yankees moved on.

But they had no defense against phantoms who could appear anywhere at any time without warning. They had no counter to enemies who seemed to know their movements before they made them. They had no answer for the bodies that started appearing in the jungle, arranged in patterns that spoke of dark rituals and inhuman appetites.

The Vietkong infrastructure in Fuoktoy province never recovered from the Australian presence. By 1969, enemy activity in the region had declined by over 80% compared to neighboring provinces. The notorious Long Tan Plantation, site of a famous battle in 1966, became so secure that Australian troops could move through it without significant risk.

Villages that had been firmly under Vietkong control for years began cooperating with government forces. The Australians had achieved what American forces with their billions of dollars and hundreds of thousands of troops could not achieve anywhere else in South Vietnam. They had won their peace of the war.

And they had done it in part by becoming the monsters the rumors described. But the story does not end there. The legacy of Australian SAS operations in Vietnam remains controversial to this day. In Australia itself, the SAS is regarded with a mixture of national pride and uncomfortable silence. The unit’s effectiveness is acknowledged, even celebrated.

The methods that produce that effectiveness are rarely discussed. American veterans who served alongside the Australians have offered varying assessments over the years. Some speak with undisguised admiration, describing the SAS as the most professional soldiers they ever encountered. Others express discomfort with what they witnessed or heard about, questioning whether the results justified the methods.

A few have suggested that the Australian approach crossed lines that should never be crossed, regardless of military necessity. The official position of both governments has remained consistent. Nothing improper occurred. Australian forces operated within the rules of engagement and the laws of armed conflict. Any rumors to the contrary are exaggerations, misunderstandings, or deliberate enemy propaganda.

But the classified files remain classified. The veterans who know the truth maintain their silence, and the whispers continue to circulate among those who study the history of special operations warfare. Perhaps the most telling detail comes from a comparison of how each nation’s veterans discuss their service. American Vietnam veterans by and large have become increasingly willing to share their experiences over the decades.

Books, documentaries, and interviews have produced a detailed record of what American forces did and experienced in Southeast Asia. Australian SAS veterans have shown no such willingness. The unit maintains a culture of operational security that extends long past the end of active service.

Men who conducted patrols in Puakui province 50 years ago still declined to discuss specific operations. Families of deceased veterans report that their loved ones never spoke of what they did in Vietnam, not even on their deathbeds. What are they protecting? What secrets could possibly matter after half a century? The most likely answer is that they are protecting themselves and each other from judgment by those who were not there.

The methods that worked in the jungle do not translate well to peaceime morality. The things that kept men alive and broke enemy morale would sound very different in a courtroom or a newspaper headline. The phantoms of Fuaktui have no interest in explaining themselves to a world that can never understand what they faced. And so the rumors persist.

The heart eating, the body displays, the dark rituals that transformed ordinary Australian men into something the Vietkong feared more than any American division. Were they true? The only honest answer is that we may never know for certain. The men who could confirm or deny the stories are passing on, taking their secrets with them.

The documents that might provide clarity remain locked in archives that show no sign of being opened. The truth, whatever it may be, seems destined to remain forever in the shadows. But perhaps that is exactly what the Australian SAS intended all along. Consider the possibility that the rumors themselves were the point.

Consider that a small force operating with limited resources in a war their larger ally was losing discovered that reputation could be more powerful than firepower. Consider that the stories about hard eating and body mutilation and demonic possession were not unwanted leaks, but carefully planted seeds designed to grow into legends that would multiply Australian effectiveness a 100fold.

If so, the operation continues to this day. The uncertainty, the mystery, the persistent whispers, all of it serves to maintain the SAS reputation as something beyond ordinary military capability. Potential enemies who research Australian special forces encounter these stories and must wonder how much is true.

What are these men really capable of? Is it worth finding out? The psychological operation that began in the jungles of Vietnam has become self-perpetuating. It passes from generation to generation of soldiers and military enthusiasts and intelligence analysts. The Australians created a legend and that legend has taken on a life of its own which raises a final uncomfortable question for American audiences.

If the Australian approach was so effective, if their methods achieved results that American firepower could not match, why did the US military not adopt those techniques? Why did American commanders not study the SAS model and implement it across Vietnam? Why did the lessons of Fuaktoy province not save American lives in other regions? The answer appears to be a combination of pride, doctrine, and moral discomfort.

American military culture could not accept that a smaller ally might have superior methods. American training systems could not produce the kind of patient, silent hunters that the Australian bush had been breeding for generations. and American values, at least officially, could not accommodate the psychological operations that gave Australian methods their terrifying edge.

So, the Americans continued fighting their way with their helicopters and artillery and body counts. They continued losing men to an enemy they could not find and could not fix in place. They continued pouring resources into a strategy that was manifestly failing, while their Australian allies, operating with a fraction of the support, achieved results that should have been impossible.

The rivalry was never officially acknowledged. The comparison was never publicly made. But every American who served alongside the Australian SAS came away with the same uncomfortable realization. They had met soldiers who were simply better at the darkest work of war, and they had no idea how to feel about it. The American sergeant who turned away from the wire at Nui dot in 1967 lived until 2015.

In his final years, suffering from the cancers that claimed so many Vietnam veterans, he occasionally spoke to family members about his service. He never wrote a memoir. He never participated in oral history projects. He never joined veteran organizations that might have pressed him for details. But one night, according to his daughter, he woke from a nightmare and said something that stayed with her long after he was gone.

I saw things over there, things I couldn’t report and couldn’t forget. The Aussies weren’t like us. They’d figured something out that we never did. They knew that in the jungle, the only rule is survival, and they were willing to do whatever it took. He paused, staring at shadows that only he could see. I think they enjoyed it. That’s what scared me most.

I think they actually enjoyed becoming what the enemy feared. He never spoke of it again. He took his secrets to the grave, just as the Australian Phantoms intended, just as they always intended. But the legacy lives on. Today, the Australian Special Air Service Regiment remains one of the most respected special operations units in the world.

They have served with distinction in East Tour, Afghanistan, Iraq, and countless other operations that remain classified. Their selection process is among the most demanding in any military. Their training produces soldiers who can operate independently in any environment on Earth, and the rumors still follow them.

In Afghanistan, Taliban fighters whispered about Australian commandos who seem to appear from nowhere and vanish without trace. In Iraq, insurgents reported that Australian special forces operated by different rules than their American counterparts. In every theater where the SAS has deployed, the same pattern emerges.

extraordinary effectiveness combined with persistent whispers about methods that exist in the shadows between official doctrine and battlefield reality. Are the modern rumors any more accurate than the Vietnam era stories? Do today’s SAS operators engage in the psychological warfare techniques that made their predecessors so feared? Or has the legend simply become self-perpetuating with each new generation of enemies projecting their fears onto soldiers who are in the end just exceptionally well-trained professionals? The Australian Defense Force offers no

comment. The veterans maintain their silence. The truth remains classified. And somewhere in barracks and training facilities scattered across the Australian continent, young men are being transformed into something their civilian selves would barely recognize. They are learning to move through the bush without leaving tracks.

They are learning to wait with inhuman patience for the perfect moment to strike. They are learning that the enemy’s mind is just another terrain to be conquered. They are becoming phantoms just like the ones who haunted Fuaktoy province half a century ago. Just like the ones who ate raw hearts in the fevered imaginations of their enemies.

Just like the ones who won their piece of an unwinable war through methods that have never been fully explained. and may never be. The jungle has long since reclaimed the old base at Newi dot. The rubber trees have grown tall where Australian tents once stood. The red mud has been washed clean of bootprints, cut or otherwise.

The wire and the sandbags and the intelligence huts have all returned to the earth. But the ghosts remain. They will always remain. And they are still watching.