April 1940. Oslo was not swallowed by prolonged fighting. The city was taken through speed and cold order. Above the rooftops and the waters of the fjord, German aircraft roared continuously, flying low and cutting across residential blocks in the harbor. The sound was not directed at military targets.

It was a declaration of control. On the ground, German soldiers moved in small units, fast and precise. They seized government offices, radio stations, and police headquarters. There was no chaos, no resistance. Norwegian civil servants remained at their desks. Shopkeepers pulled down metal shutters. Residents watched from behind curtains, holding their breath.

The capital continued to function, but its soul had changed hands. The silence that settled over Oslo was [music] not accidental. It was arranged. Within days, the first signs appeared. People summoned for questioning did not [music] return. Names vanished from offices and schools. Rumors spread quickly about blacklists and interrogations conducted [music] behind closed doors. No one knew the criteria.

That uncertainty itself [music] created an invisible but constant pressure. Real power did not rest with the [music] Vermach units on the streets. Behind them operated another apparatus, less visible but more deeply [music] embedded. There were no parades, no flags. This machinery moved into [music] police stations, basement, and interrogation rooms.

Its task was not to control [music] territory, but to map people, to identify who needed to be neutralized before any spark of resistance could take shape. At the center of this apparatus [music] stood Sigfrieded Femer, a Gustapo officer with a polite exterior yet holding power over life and death in the shadows.

To prisoners, he was the architect of interrogations without witnesses. To the Nazi regime, [music] he was the key to turning Oslo into a muted city where resistance was strangled before it could emerge. What made Famer a true nightmare, however, was not only the interrogations, [music] but the mask he wore. He did not arrive as a monster.

He appeared with the manners of a gentleman, [music] using charm to create trust before destroying it. To understand how an educated man became such a cold instrument [music] of killing, it is not enough to look at Oslo. We must move backward in time [music] to where the first seeds of hatred and the hunger for power were planted in a child.

The origin of a monster. [music] Sigfrieded Femer was born on January 10th, 1911 in Munich. On paper, he was German. In terms of identity, his background was more complex. His parents were Baltic Germans who had lived for years in the Russian Empire [music] and held Russian citizenship before World War I.

From birth, Femer belonged to a world where borders, nationality, and political order were in constant flux. His early years were spent in [music] Moscow during a period of war and revolution. The city was no longer a stable [music] center of imperial authority, but a space of prolonged chaos. Order collapsed. Power shifted [music] in the streets.

Daily life was shaped by scarcity and constant fear. For a child, the world was not governed by law, but by brute [music] force. From these experiences, Famemer formed a lasting [music] psychological association. Chaos meant danger. order, even harsh order, was more reliable than total collapse. This was not a passing impression.

It became the foundation of how he later viewed society. [music] In 1918, Femer’s [music] family left Russia, returned to Germany, and settled in Berlin. But postwar Germany offered no stability. The Vhimmer Republic [music] was marked by inflation, unemployment, political conflict, and [music] street violence. The state existed, but its authority was constantly challenged.

To Fymer, [music] this was not an environment of freedom, but a repetition of the insecurity he [music] had already known. In this setting, Fymer did not seek debate or individual [music] creativity. He sought structure, discipline, and clear order. His decision to study law at the University of Berlin reflected [music] that choice.

Law in his understanding was not a means to protect [music] individuals from the state but a tool for the state to impose order on society. In this setting, Fymer did not seek debate or individual [music] creativity. He sought structure, discipline, and clear order. His decision to study law at the University of Berlin reflected [music] that choice.

Law, in his understanding, was not a means to protect individuals from the state, but a tool for the state to impose order on society. At that moment, Femer was not yet directly [music] involved in violence. He was a young, well-trained intellectual, but the psychological foundation was already complete, [music] an obsession with chaos, deep hostility toward communism, and the belief that society [music] could exist only under strict control.

As the Nazi regime moved toward power, Fymer did not need to change. He only had to step into the position the system had already prepared for people like him. The rise within Nazi Germany. When Sief freed Fymer joined the Nazi party on January 1st, [music] 1930, he was still only a law student in Berlin. Yet the timing carried decisive significance.

This was not an act of following [music] power once victory was assured, but an early choice that revealed a clear ideological orientation. His low [music] party membership number indicates a strong commitment from the very beginning. For Famemer, [music] the Nazi party was not merely a political organization.

It represented a promise of order, something he had consistently sought since the chaos [music] of his childhood. In his view, society could exist only when power was centralized and discipline was enforced from the top down. In 1933, Fymer graduated with a law degree just as Adolf Hitler came to power. This coincidence [music] marked an important turning point.

The new state required individuals with legal expertise [music] to legitimize authority and Femer entered professional life within a system that was restructuring [music] the entire legal framework to serve ideology. In 1934, he married Anie Villa [music] and began working for the Berlin police. This was a crucial phase.

Police work taught FMA how to transform coercion into administrative [music] procedure, turning arrests and interrogations into steps shielded by legal formality. On October 1st, 1934, [music] Fymer joined the Gestapo. He was introduced to Reinhard Hydrrich, who was building the Gestapo into the regime’s central instrument [music] of social control.

To Hydrrich, Fymer represented the ideal type of officer. Educated, [music] disciplined, and unwilling to question ultimate objectives. Fyur was quickly valued for his exceptional memory for faces and [music] voices. This ability proved especially useful in counter inelligence and the pursuit of underground networks. He [music] was tasked with monitoring, identifying, and dismantling left-wing organizations where patience and information [music] management mattered more than overt displays of force.

From 1937 to 1939, Fymer [music] served as head of the counter inelligence department in Kursin in what is now northern Poland. This was a position with little public visibility, [music] but significant training value. There he learned how to run a unit, [music] manage information, and maintain constant pressure on monitored targets, all in an environment with limited oversight from the [music] center.

By the late 1930s, Femer was no longer a young lawyer or an ordinary policeman. He had become a fully trained security officer [music] accustomed to exercising power from the shadows. More importantly, [music] he had absorbed a core Gestapo principle. Order did not require spectacle, but was maintained [music] through the quiet presence of fear.

As the war expanded across Europe and Germany prepared to control occupied territories, [music] figures like Fymer became especially necessary. They did not fight on the battlefield, but converted military victory [music] into long-term control. In the spring of 1940, Fyur was assigned to such a mission. The mission in Norway.

On April 9th, 1940, [music] German forces launched Operation Wesserubong and entered Norway at high speed. [music] By June 1940, the Norwegian government was forced to surrender. Militarily, the campaign ended quickly. For Berlin, however, occupation was only beginning. Norway held critical [music] strategic value. Deep water ports opened access to the North Sea.

Shipping routes protected [music] iron or transport from Sweden. and the long coastline formed a northern shield for Germany. Controlling Norway meant not only holding territory, but maintaining long-term stability [music] in a society with a strong tradition of political independence and a high standard of living. This required a control [music] mechanism more refined than conventional military force.

Although a puppet government was established, [music] real power rapidly shifted to German security agencies. The Gestapo assumed a central role. Their task was not routine [music] administration, but identifying, monitoring, and neutralizing any [music] potential resistance from its earliest stages.

On April 29th, 1940, Sigfrieded Fairmer arrived in Oslo after completing specialized [music] training for security police units. The assignment was carefully calculated. Femur was chosen for his [music] counterintelligence experience and his ability to operate systems of control [music] within a civilian environment where overt violence could easily prove counterproductive.

In Oslo, FEMA quickly integrated into the emerging security apparatus. The Vermacht was visible on the streets, but decisions concerning internal security were made in discrete offices. The Gustapo constructed a layered surveillance system, combining administrative [music] records, mail control, and information gathered from the local population.

Informer [music] networks became a key tool. Neighbors were encouraged to report behavior deemed suspicious. Mail was selectively censored. Cafes, [music] boarding houses, and gathering places were quietly monitored. Oslo’s open social [music] space gradually fragmented into zones of uncertainty where people could no longer be sure who was watching.

Famous stood out for his ability to communicate [music] directly in Norwegian. This allowed him to engage targets without intermediaries and to accurately assess reactions and psychological states [music] during initial meetings, which were often disguised as routine administrative matters before shifting into tighter [music] control.

Under famous coordination, the Gustapo in Oslo focused on mapping society. Personal, [music] professional, and political relationships were continuously recorded and cross-cheed. The objective was not to respond to resistance after it occurred, but to prevent it in advance. By the end of [music] 1940, the German security apparatus in Norway was operating with relative stability.

Military forces [music] provided the outer framework of control while the Gustapo managed control from within. Within this [music] structure, Fymer did not shape highle strategy. His role was to turn general directives [music] into concrete procedures, convert scattered information into files, and [music] make the presence of the Gustapo a constant reality for Norwegian society.

The dual [music] face of Fymer in occupied Oslo. Sief freed Femer did not appear as someone who [music] spread fear openly. He presented himself as a calm security officer, neatly [music] dressed, often walking his dog along the central streets. No threats, no signs of urgency. [music] To many residents, he seemed more like an administrative official than the man directing a repression [music] apparatus.

Femer’s decisive advantage was language. He spoke Norwegian fluently and did not need an interpreter. This allowed him to communicate [music] directly, grasp psychological nuances, and adjust his approach to each individual. Initial meetings were usually conducted in a normal atmosphere, sometimes even friendly, a soft voice, casual questions.

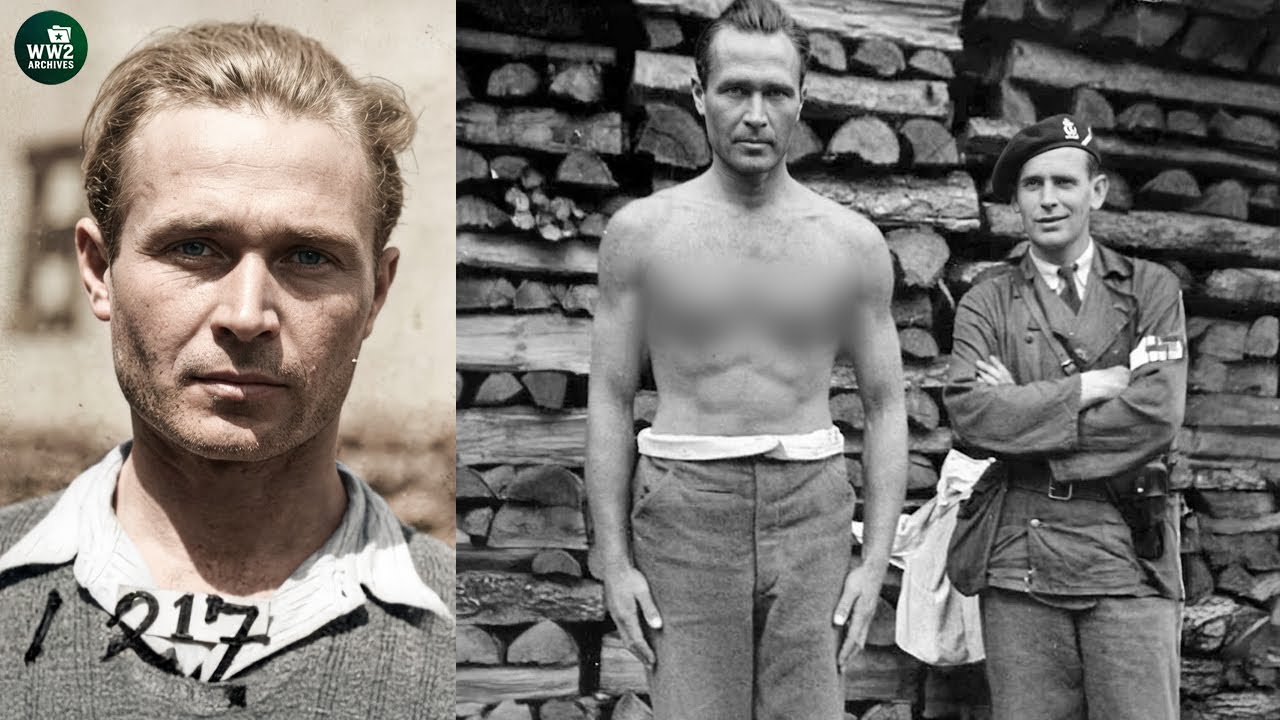

This was a deliberate technique, not a coincidence. Some resistance [music] members later recalled that their first encounter with Famer did not feel dangerous. Ida Nikoline Manis once described him as polite, cheerful, [music] and easy to like. That impression did not reflect his true nature, but it showed how effective the facade he maintained [music] could be.

Within that seemingly safe space, Fymer began to guide his counterpart. [music] Early questions focused on personal life and social relationships. Information came not only from answers but from hesitation, [music] eye contact, and small reactions. Once the overall picture became clear, the atmosphere [music] shifted. The voice grew drier.

The questions turned to specific connections. At that point, [music] the position of the person being questioned had already changed, even though the room itself [music] had not. This constant shifting was characteristic of how Famer exercised power. He did not remain in a single mode, but alternated between softness and pressure, between social interaction and administrative coercion.

The goal was not to provoke an immediate reaction, [music] but to disorient the other person so that the line between cooperation and control [music] disappeared. From early 1941, when directives allowing stronger interrogation [music] measures were issued, Femer took part in drafting and distributing internal guidelines in Oslo.

On paper, these documents were framed as technical procedures with formal limits. [music] In practice, their application went far beyond those constraints. Measures that [music] applied physical and psychological pressure were used more frequently. Fymer did [music] not carry out everything himself, but he coordinated and supervised.

Decisions were placed within [music] an administrative framework, turning harm to individuals into a component of a process that was recorded and reported. A symbol of brutality and resistance in Oslo. Sief freed famous methods [music] gradually became consistent. He did not rely on a single form of pressure. Instead, he constantly shifted between calm and coercion, between social interaction and harsh measures.

[music] The objective was not rapid information gathering, but to make the other side believe that every option led to the same outcome. In famous logic, [music] resistance had to be proven meaningless. This approach did not unfold in a single moment, but over repeated encounters. One meeting might begin with ordinary conversation [music] and end with increased pressure.

The next would occur in a different setting with a different intensity. This constant variation produced prolonged [music] disorientation, making it difficult for those detained to maintain psychological stability. The case of Lorett Sand became a [music] clear example of the limits of this method. Sand, then 62 years old, was a central [music] figure in the resistance network.

In interrogations, he refused to cooperate. In response, coercive measures [music] were applied at a high level and repeated. His body suffered severe injury. He was treated to keep him alive [music] and then returned to the cycle of control. This process was not intended as immediate [music] punishment, but as a gradual effort to break his will.

The outcome did not follow Femer’s calculations. Sand [music] provided no information. Instead, he became a symbol of endurance within the Norwegian resistance. What happened to him spread by word [music] of mouth, reinforcing the belief that silence and non-ooperation could still [music] exist even under extreme pressure.

From that point on, the Gestapo was no longer seen only [music] as a control apparatus, but as a force facing increasingly organized opposition. Meanwhile, [music] the activities of the Melog resistance did not decline. Acts of sabotage [music] continued. Information kept flowing to the Allies. Secret radio [music] stations appeared and disappeared.

Each small failure to shut down these networks highlighted [music] a reality. Control through fear did not create absolute stability. On July 4th, 1944, [music] Fymer was seriously wounded during an operation targeting a Milog broadcasting site. He was hit by gunfire and explosive fragments to the head. The incident [music] showed that the security apparatus he coordinated was no longer beyond the reach of the resistance.

Even so, after about 2 months of recovery, Fymer returned [music] to work and continued his role without changing his methods. In the final phase of the war, as the overall situation [music] clearly turned against Germany, Fymer was appointed head of department 4, responsible for the Gestapo in Oslo. His task was no longer to establish [music] long-term control, but to delay collapse.

Fear was used as a tool to [music] buy time, keeping the machinery running for a few more days at a time. Collapse and a failed escape. On May 8th, [music] 1945, Germany accepted surrender. In Oslo, the German security apparatus shifted into self-dissolution. Files were destroyed. Personnel tried to disappear from [music] positions they had once controlled.

The Gustapo, which had operated in the shadows, was [music] now forced to retreat amid chaos. Sigfigried Femer did not attempt to confront the situation or hold his ground. [music] He chose to flee. famous severed all identifying markers, disguised himself as a low-ranking soldier, [music] and blended into prisoner of war camps.

His plan was to leave Norway and cross into Sweden, where he believed he could merge into the chaotic [music] flow of postwar refugees. Femer’s mistake did not come from the plan itself, but from personal habit. On May 31st, 1945, [music] while in hiding, he used a telephone to contact a woman he knew to ask about his dog.

The call was detected by Allied monitoring systems. Location information quickly led to his [music] arrest. Fymer was interrogated by British intelligence. Reports described him as highly [music] educated, analytically capable, articulate, and confident. Yet that very smoothness [music] also made interrogators cautious. He did not appear panicked.

Instead, Fymer presented [music] himself as a valuable source of information in the emerging ideological confrontation [music] of the post-war period. While in custody, Fymer continued to rely on familiar skills. He wrote [music] detailed reports on the structure and operating methods of the Gustapo in Norway, hoping to present himself as [music] a cooperative figure.

His goal was to be transferred to an area under American control [music] where his anti-communist stance might serve as an advantage. However, the judicial process in Norway [music] did not focus on the defendant’s intentions or arguments. The emphasis lay on concrete [music] actions. Surviving witnesses described the long-term consequences they suffered after interrogations.

medical records, [music] testimony, and administrative documents showed that the decisions were not impulsive acts, [music] but part of an organized and sustained system. Femer’s education and coordinating [music] role were not treated as mitigating factors. On the contrary, they were considered aggravating [music] circumstances, demonstrating that his actions were carried out with full awareness of their consequences.

This was not individual deviation [music] but the calculated exercise of power. On June 27th [music] 1947 the court issued the maximum sentence. The verdict was upheld on appeal. On March 16th [music] 1948 Sigfrieded Femer was executed by firing squad at Akashus Fortress in Oslo. He was 37 years old. The story ends not with a dramatic collapse, but [music] with a cold administrative conclusion.

A man who had controlled society through files, interrogations, [music] and fear was ultimately recorded in the same kind of documents he had once produced. That marked the end of a path built on enforced order rather than chaos. From a historical research perspective, [music] the most troubling aspect of this story is not the scale of harm Famemer caused, but how an educated individual could fully integrate [music] into a system that inflicted damage without having to shatter his own self-image.

The path [music] was not marked by extreme decisions, but by gradual adaptation to a new order. Totalitarian systems [music] do not survive through isolated acts of violence, but through people who believe they are merely fulfilling assigned tasks. When a system operates smoothly, [music] individual responsibility dissolves into procedure.

Harmful conduct is no longer seen as a moral choice, but as a technical duty performed [music] to specification. The warning history offers here is not directed at a [music] distant past, but speaks directly to the present and the future. knowledge, organizational ability, and [music] discipline, when separated from self-restraint, can become tools for aims that run against human values.

Not every legal action [music] is a just one. For later generations, the core lesson is not simply recognizing evil, [music] but recognizing the moment to stop. When a system demands that individuals [music] abandon critical judgment in exchange for stability, that is when danger begins. Refusal in many cases is not betrayal [music] but responsibility.

History provides no absolute formula for prevention. But it leaves one clear requirement. Each individual [music] must retain the right to question even when everything around them is presented as reasonable and necessary. That capacity is the final boundary between [music] order and moral decay.