At 11:15 on the morning of April 9th, 1944, Lieutenant Commander George Castleman stood on the bridge of the USS Pillsbury and stared across a restless Atlantic. The war had taught him patience. 10 months of hunting German submarines had brought him dozens of attacks and not a single capture.

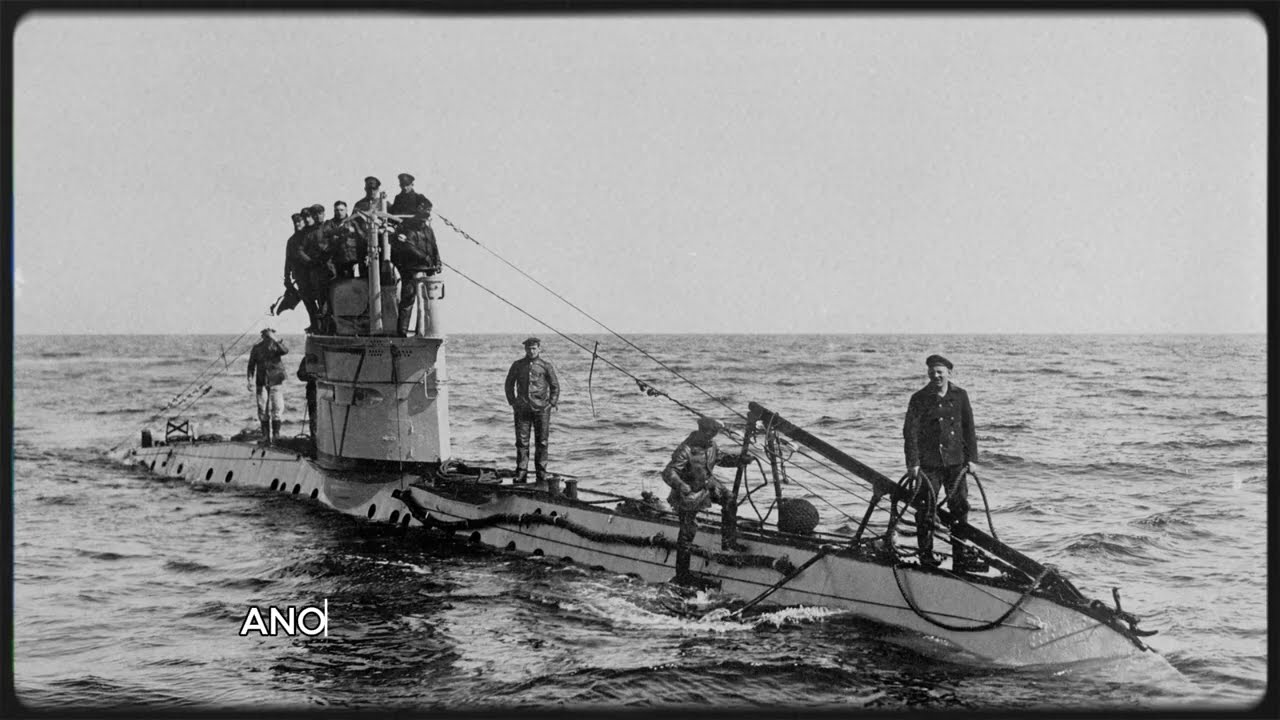

Then, through drifting spray and broken foam, something impossible happened. A dark shape burst through the surface just 700 yd off his starboard bow. A German yubot, battered and wounded, rose from the depths like a dying animal dragged into the light. It was U515 commanded by Wernner Hank, one of the most feared submarine aces in the German Navy.

25 Allied ships lay on the bottom because of him. Hundreds of men, women, and children had drowned when he torpedoed the troop ship ceramic. Now his submarine was crippled, forced up after hours of relentless depth charging. German sailors spilled onto the deck, some running for the guns, others leaping straight into the sea. Castlemen’s ship opened fire.

So did the escorts beside her. Bullets tore across the cunning tower. Rockets streaked down from circling aircraft. Within minutes, the bow of U515 lifted. The stern slid under and the Atlantic swallowed her whole. 44 Germans were dragged from the water, including Hank himself. By every rule of war, it was a perfect victory.

Another enemy submarine destroyed. Another threat erased. But Captain Daniel Gallery, commanding the Hunter Killer group from the escort carrier Guadal Canal, did not see victory. He saw regret. He had watched that submarine float on the surface for nearly 10 minutes before she finally slipped under. 10 minutes.

Enough time to do something no American had done in more than a century. Enough time to board her. The thought would not leave him. What if they had taken her instead of sinking her? Inside a German submarine lay treasures beyond measure. Enigma cipher machines, code books, new torpedoes, secrets that could unravel the entire yubot war.

No American warship had captured an enemy vessel at sea since 1815. The Navy did not train for it. No one had even imagined it possible. German crews were taught to scuttle their boats within minutes. They opened sea valves, set demolition charges, smashed machines, burned codes. They would rather die than surrender their secrets. But Gallery decided that the next time they would try. When task group 22.

3 returned to Norfolk, he gave an order that stunned his captains. Every ship would form a boarding party. They would train. They would prepare. And when the next Yubot surfaced, they would attempt what the United States Navy had not done in 129 years. On the Pillsbury, Castleman gathered eight men for the mission.

Their leader would be Lieutenant Junior Grade Albert David, a quiet, stocky 41-year-old engineer who had worked his way up from enlisted ranks over 25 years. He knew pipes and valves and flooding and machinery. He had never boarded an enemy ship. No one alive had. Every day after sailing, David drilled his men. They practiced climbing rails, leaping from boats, memorizing blurry photographs of German submarines.

They rehearsed disarming bombs in the dark. They knew the risks. The submarine might dive with them aboard. It might explode beneath their feet. They had 3 to 5 minutes, maybe less, to stop a sinking steel coffin rigged with explosives. In early June, the task group turned south toward Africa. Days passed without contact. Then, on the morning of June 4th, as they prepared to leave the patrol zone, sonar reported a submerged contact racing straight toward the carrier.

Depth charges thundered into the sea. Oil bubbled up. 6 minutes later, the submarine burst to the surface, crippled and circling helplessly. Her rudder was jammed. Water poured through shattered pipes. German sailors tried to fight, then fled. On the bridge of the Pillsbury, Castleman did not hesitate. He ordered the whaleboat lowered.

David and his men cast off and drove straight toward the circling submarine. Oil sllicked the water. Wounded Germans shouted nearby. David ignored them. He seized the railing, hauled himself onto the rolling deck, and led his men through the open hatch. Inside, darkness and chaos ruled. Water sprayed from broken pipes. The deck slanted sharply.

The submarine was flooding fast. Somewhere below, demolition charges ticked toward detonation. They split up and worked in silence. One man closed a flooding valve just in time. Another found explosives wired into the hole and tore out the detonators with shaking hands. They crawled through oily water, tracing pipes, sealing hatches, stopping leaks one by one.

Above them, the submarine drifted into the Pillsbury and crushed the whaleboat between the holes. The destroyer escort flooded three compartments, but the boarding party stayed. They had stopped the scuttling. Hours later, another engineer, Commander Earl Troino, climbed aboard and began the impossible task of saving thecaptured submarine.

He traced German systems by touch, redirected pumps, stabilized flooding. Slowly, against all odds, U505 stayed afloat. Then the real prize emerged. Enigma machines, fresh code books, patrol charts, acoustic homing torpedoes no Allied engineer had ever examined. 900 lb of classified material lay stacked on the deck and suddenly victory became danger.

If Germany learned the submarine had been captured intact, every code would change overnight. The intelligence would be worthless. The coming invasion of France could be compromised. Gallery ordered absolute silence. No logs, no radio reports, no letters home. The prisoners were hidden. Their families told they were dead.

For 15 storm rack days, the task group towed the wounded submarine across the Atlantic to Bermuda. Then she vanished into secrecy, repainted and renamed. Her story locked away. In England at Bletchley Park, codereers opened the books and machines, and suddenly the Atlantic spoke. Submarine positions appeared on maps. Patrol zones glowed with danger.

Convoys steered away from traps. Hunter killer groups struck with precision. Engineers dismantled the acoustic torpedoes and invented decoys that saved countless ships. The Battle of the Atlantic turned, and still the secret held. Not a single sailor spoke. Months later, when Germany launched one last desperate submarine attack toward America, the same men of the Pillsbury hunted them down again.

They watched comrades die, sank the last enemy boats, and escorted the final surrender across gray seas. When the war ended, the truth finally emerged. Albert David received the Medal of Honor, though he never lived to see it. U505 toured America as a war trophy, then nearly vanished beneath Target practice shells until Daniel Gallery saved her once more.

Today, she rests in a quiet hall in Chicago. her steel hole preserved exactly as it stood that day in 1944. Visitors walk through the control room where water once poured in. They stand beside the valves that saved her. They look at the Enigma machines that changed the war. And few realize that eight sailors armed with nothing but wrenches and courage once jumped onto a sinking enemy submarine and altered the course of history.

If you’re still here, thank you for listening to their story. These men asked for no monuments. They asked only to be remembered. And now because you’re here, they