The tape stopped. Bob Dylan looked at the unfinished song and said quietly, “I’m not going to finish this.” Nashville, 1978. A small studio on Music Row called Woodland Sound. The kind of place where the floorboards creaked and the walls held 30 years of cigarette smoke and late night sessions.

Bob Dylan had rented it for 3 weeks to work on what would eventually become the album Street Legal. It was 2:00 a.m. on a Tuesday. The engineer had gone home hours ago, leaving Dylan alone with the tape machine, his guitar, and a half-written song that had been haunting him for 6 months. The song had no title, just a working name scribbled on the track sheet.

For Sarah, three verses written, melody mostly there, but the fourth verse, the one that would make sense of everything that came before, wouldn’t come. Dylan had tried. God knows he tried. He’d rewritten it seven times. Changed keys twice. Played it fast, played it slow, played it with fury, and played it with tenderness. Nothing worked.

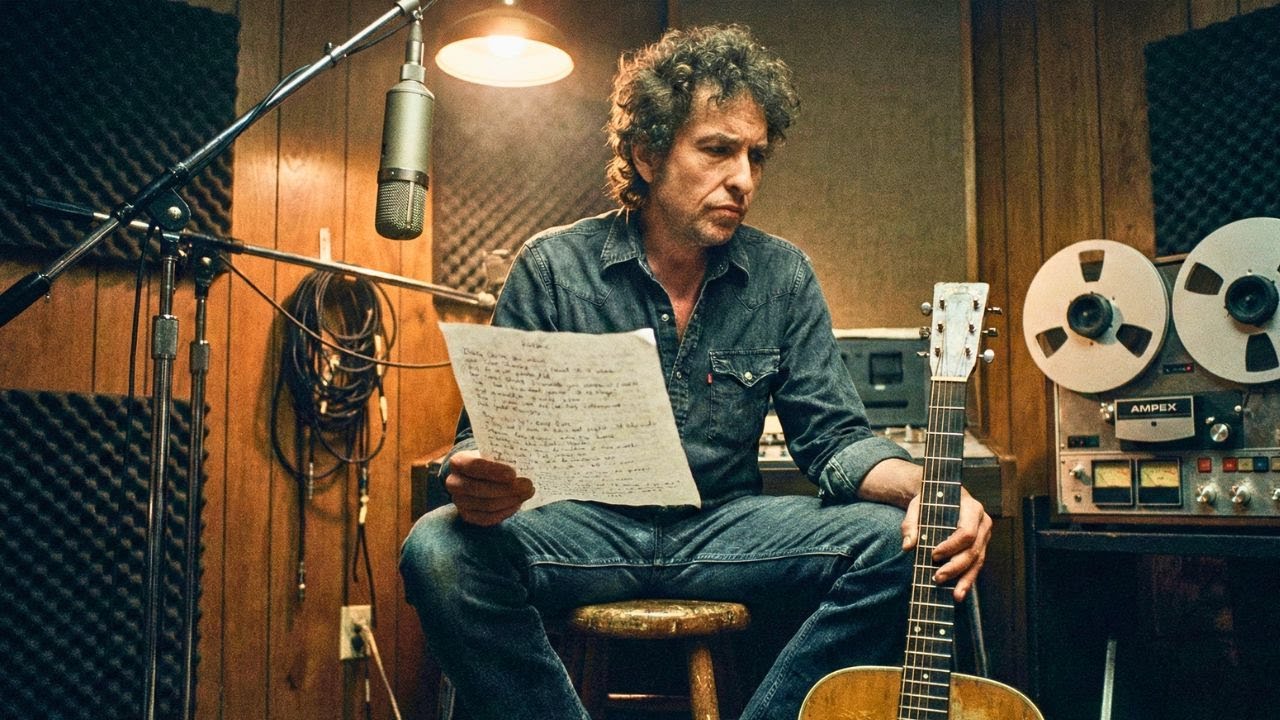

The song remained incomplete. A question without an answer. He sat on the wooden stool in the recording booth, guitar across his lap, looking at the handwritten lyrics spread on the music stand in front of him. The tape machine’s reels had stopped spinning. The red recording light was off. In that silence, Dylan made a decision he would never explain.

He carefully tore the lyric sheet from his notebook, folded it twice, and slipped it into a manila envelope that was sitting on the console. He wrote a single line on the outside. Finish this if you want. It’s yours. B. Then he left it on top of the tape machine and walked out of Woodland Sound Studios at 2:47 a.m. never mentioning the song again.

In 1978, in a small Nashville studio, Bob Dylan stopped a tape, looked at an unfinished song, and quietly said, “I’m not going to finish this.” 30 years later, the secret behind that decision finally emerged. To understand why Dylan gave that song away, you need to understand who it was written for. And more importantly, you need to understand the promise he’d broken.

Sarah Loans met Bob Dylan in 1964. She was a model and playboy bunny working in New York. Quietly beautiful in a way that made men forget their rehearsed lines. Dylan was already becoming what he’d spend the rest of his life running from. A voice of a generation, a prophet, an icon. he never wanted to be.

They married in 1965, secretly away from cameras and journalists and everyone who wanted to own a piece of him. They had four children together. For a while, Dylan disappeared from the public eye almost entirely, hiding in Woodstock, trying to be something simpler than Bob Dylan. Sarah was the one person who’d seen him without the mythology.

She’d watched him struggle with cords at 3:00 a.m. She’d held him through the panic attacks that came with fame. She’d been there when the weight of being, the voice of a generation, nearly crushed him. “I don’t want to be anyone’s voice,” he told her once, sitting on their porch in Woodstock, holding her hand.

“I just want to write songs, then write them for me,” she’d said. “Forget everyone else. Just write them for me.” He promised her he would. That no matter what happened with his career, with his image, with the expectations. He’d always write honestly for her, about her, even if no one else ever heard them.

For years, he kept that promise. Songs that no one knew were about Sarah. Melodies hummed in their kitchen. Verses written while she slept. music that existed in the space between Bob Dylan the icon and Bob the man who was trying to figure out how to be a husband but fame is a hungry thing. Tur stretched longer. Studios demanded more.

The mythology grew heavier. Dylan started drinking more, sleeping less, disappearing into the persona even when he came home. The marriage began to fracture in ways they both pretended not to notice. Arguments that lasted for days. silences that lasted longer. Dylan would leave for months on tour and come back to find Sarah had rearranged the furniture, a quiet metaphor for how much had shifted while he was gone.

In 1977, Sarah filed for divorce. The proceedings were bitter, public, expensive. Lawyers said things Dylan wished he could unhear. The press documented every detail. Their children were caught in the middle. Dylan handled it the only way he knew how. He disappeared into his music. He wrote an entire album about the dissolution of their marriage.

Raw, angry, griefstricken songs that would become blood on the tracks critics called it his masterpiece. Dylan called it the most painful thing he’d ever done. But there was one song he couldn’t finish for Sarah. He’d started it in 1976 during a brief moment when they tried to reconcile. It was supposed to be an apology, an acknowledgement of everything he’d done wrong, a song that said what he couldn’t say in the lawyer’s offices or the courtroom, or the long-distance phone calls that always ended in silence. I promise you,

I’d write honestly, but honest don’t come easy when you’re running from your name. I built these walls of mystery and locked us both inside until forgetting felt the same. The first three verses were brutal in their self-awareness. Dylan holding himself accountable in ways he rarely did. Admitting he’d chosen the mythology over the marriage that he’d hidden behind Bob Dylan when Sarah needed Bob.

But the fourth verse, the resolution, the path forward, the answer to the devastation of the first three wouldn’t come because Dylan didn’t have an answer. The marriage was over. Sarah had moved on and Dylan was left holding a song that asked questions he couldn’t answer. Dylan didn’t explain himself. He never did.

For 18 months, he carried for Sarah with him. Tried to finish it in hotel rooms, inter buses, and studios across three continents. The melody was perfect. The arrangement wrote itself, but every time he tried to write that fourth verse, the words felt like lies. How do you write an ending to something you destroyed? How do you find resolution when you’re the reason there isn’t any? The song remained incomplete.

A musical representation of what their marriage had become. Something beautiful that would never have closure. Subscribe and leave a comment because the most important part of this story is still unfolding. On that November night in 1978 at Woodland Sound Studios, Dylan finally accepted what he’d known for months.

He couldn’t finish this song, not because he lacked the skill. He’d written hundreds of songs, many of them considered among the greatest in American music. He couldn’t finish it because finishing it would be a lie. The song wasn’t meant to have an ending. The marriage didn’t have closure. Sarah had moved on to build a life without him.

Their children were learning to navigate holidays split between parents. The story was incomplete and pretending otherwise in a fourth verse would dishonor everything the first three verses admitted. So Dylan did something he’d never done before and would never do again. He gave the song away.

He left that manila envelope on the tape machine, walked out of Woodland Sound, and flew back to California the next morning. The studio owner, a man named Marcus Webb, found the envelope 3 days later while preparing the studio for its next client. Marcus opened it, saw Dylan’s handwriting, and understood immediately that he was holding something no one was supposed to see.

An unfinished Bob Dylan song given away with no legal paperwork, no contracts, no rights negotiated, just a note. Finish this if you want. It’s yours. Marcus Webb was a session musician who’ played on hundreds of records, but had never written a song of his own that anyone recorded. He was 53 years old, running a studio to pay bills, watching younger musicians chase the dreams he’d given up on decades ago.

He read Dylan’s three verses. listened to the rough recording Dylan had left on the tape. And something in those incomplete lyrics spoke to him in a way that had nothing to do with Bob Dylan’s fame and everything to do with Marcus’s own life. Marcus had been married once, divorced after 7 years. He’d been so focused on becoming a successful musician that he’d ignored his wife’s growing loneliness.

By the time he noticed, she was already gone. He’d never written her the apology she deserved. For two weeks, Marcus left the envelope untouched on his desk. He’d walk past it every morning, make coffee, set up for the day’s sessions, and pretend he wasn’t thinking about it. Then one night, alone in the studio, he opened the envelope again.

He played Dylan’s recording one more time, and he understood why Dylan couldn’t finish it. Because some apologies come too late for the person they’re meant for. But that doesn’t mean they shouldn’t be written. Marcus Webb sat down with his own guitar and wrote a fourth verse. Not from Bob Dylan’s perspective from his own.

A verse about learning to live with what you’ve broken. About understanding that some damage can’t be undone, but can be acknowledged. About the small, quiet grace of finally being honest, even when honesty doesn’t fix anything. He recorded it in one take, his voice rough and untrained. Nothing like Dylan’s.

He pressed two copies onto vinyl. One for himself, one that he mailed to an address in California he’d found in an old studio rolodex. Sarah Dylan’s address. He never heard back. He never expected to. Away from the spotlight, Dylan made a choice no one expected. The song that became known as for Sarah Marcus’ ending never saw commercial release.

Marcus never tried to sell it, never shopped it to labels, never claimed authorship despite Dylan’s note giving him full rights. The song lived in the strange liinal space of music that exists but doesn’t officially exist. But in the tightnit Nashville session musician community, word spread the story of Dylan’s unfinished song given away at 2:00 a.m.

finished by a studio owner who understood something about the weight of apologies that come too late. Over the years, maybe a hundred people heard Marcus’ recording. Session players who’d stopped by Woodland Sound. Songwriters who’d hear the story and asked to listen. Young musicians trying to understand what it means when your heroes show you their unfinished work.

What they heard wasn’t a Bob Dylan song. It was something stranger and more honest. Two men a generation apart writing verses to the same apology. Either one expecting forgiveness. both understanding that some things need to be said even when saying them changes nothing. Dylan never publicly acknowledged the song’s existence.

In interviews over the decades, when asked about unreleased material, he’d mentioned dozens of tracks that never made albums. He never mentioned for Sarah. But in 2004, 26 years after that night in Woodland Sound, something unexpected happened. Marcus Webb had a heart attack. He survived but barely. While recovering, he decided to finally close Woodland Sound Studios.

He was 79 years old. His hands shook too much to play guitar anymore. It was time. He hosted a small gathering for the musicians who’ passed through his studio over 50 years. Maybe 40 people showed up. Session players, engineers, a few artists who’ recorded their first demos there. Near the end of the evening, Marcus played for Sarah Marcus’ ending one final time.

He explained how he’d gotten it. He played both Dylan’s three verses and his own fourth verse. He told the whole story. When the song ended, there was that particular silence that follows something genuine. Then someone in the back of the room started clapping slowly, deliberately. The crowd turned. Bob Dylan was standing by the door.

No one had seen him come in. He was wearing a black jacket and that distant expression he always carried. He walked through the silent room to where Marcus stood. They looked at each other, two men who had shared three verses and a silence that lasted 26 years. Dylan didn’t say anything about the song. He didn’t thank Marcus.

He didn’t explain why he’d come. He simply reached into his jacket pocket and pulled out a worn piece of paper, the original lyric sheet, the one he’d left in that envelope in 1978. He handed it to Marcus. “You finished it right,” Dylan said quietly. “Better than I could have.” Marcus’s hands shook as he took the paper.

“I just wrote what I understood,” Dylan nodded. “That’s all any of us can do. Share and subscribe. Some stories deserve to be remembered. Marcus Webb died six months later. In his will, he left the original lyric sheet to the Country Music Hall of Fame with instructions that had never be displayed, only archived. Some things he’d written are meant to be known, not seen. Dylan never recorded.

For Sarah, he never mentioned Marcus Webb in interviews. But those who were in that studio that night remember the man who’d spent 50 years running from being an icon had come back to honor the session player who had understood that some apologies matter even when they don’t fix anything. The unfinished songs stayed unfinished and somehow that was the point.