Dylan lowered his guitar. He didn’t approach the microphone. He stood there in front of 15,000 people without saying a word until a voice rose from the crowd. The Civic Center, Portland, Oregon. November 1975. The air thick with cigarette smoke and anticipation. 15,000 people packed into seats, standing in aisles, pressed against walls. They’d waited hours.

Some had waited years. Bob Dylan was on tour. The Rolling Thunder review. A traveling circus of poets, musicians, and misfits moving through America like a ghost from another era. Dylan wore white face paint some nights. Other nights he wore a mask. Sometimes he played the old songs. Sometimes he didn’t. Tonight the stage was set.

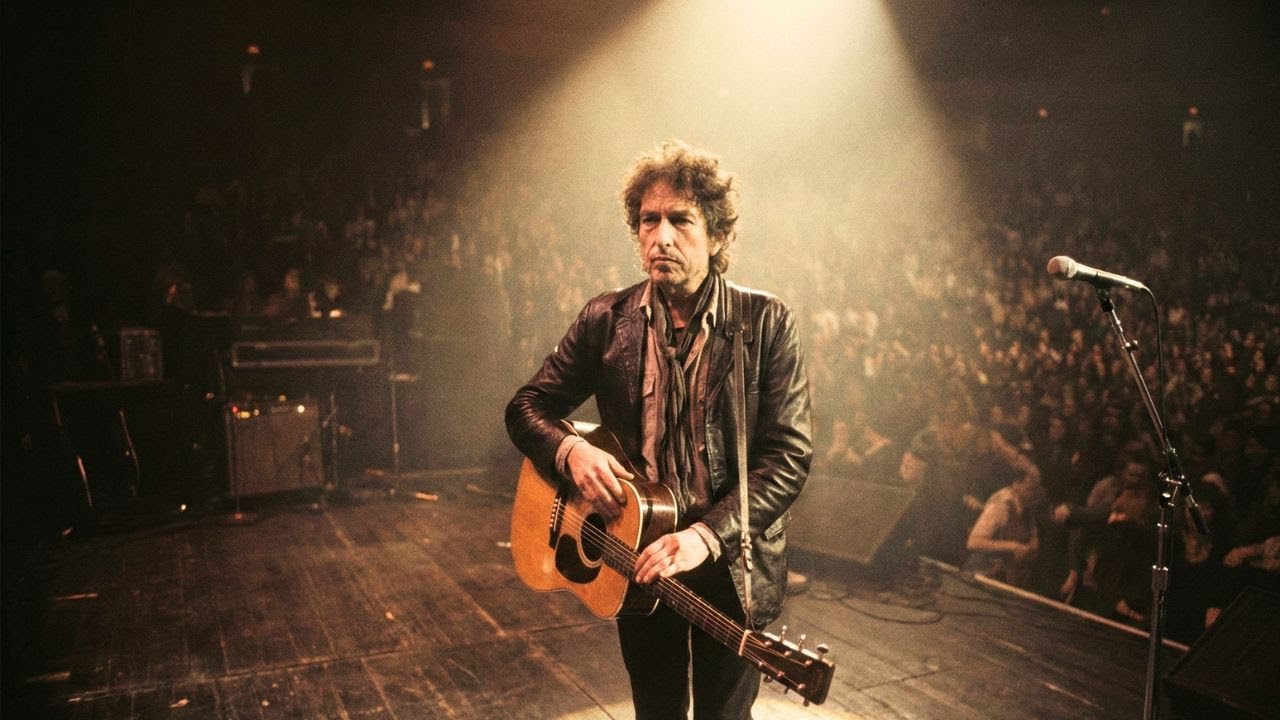

Guitar stands, microphones, amplifiers humming low. The band was ready backstage. The audience was ready. Everything was ready except Bob Dylan. He walked onto the stage alone. No introduction, no fanfare, just Dylan in a dark jacket, his curly hair wild, his face showing every year of the decade he’d spent being called the voice of a generation.

A title he never asked for and spent most of his energy trying to escape. He stopped at center stage. The spotlight found him. The crowd erupted. That sound of 15,000 people releasing anticipation in one collective roar. Cheering, screaming, whistling. Dylan stood still and let it wash over him, didn’t wave, didn’t smile, just stood there holding his guitar by the neck, letting it hang at his side.

The cheering went on for 30 seconds, 45, a full minute. Then it began to fade. People expected him to say something, to play something, to do what performers do. Dylan didn’t move. The guitar stayed at his side. His hand rested on it, but he didn’t lift it into playing position. He didn’t step toward the microphone.

He just stood there looking out at the crowd with that inscrable expression that could mean anything or nothing. The silence grew uncomfortable. Confused whispers rippled through the venue. Something was wrong. This wasn’t how concerts worked. Backstage, the tour manager grabbed a phone. What’s he doing? Why isn’t he playing? Nobody knew. Dylan didn’t explain himself.

He never did. To understand what happened on that stage, you need to understand what happened two weeks earlier. Dylan had been on the road for months. The Rolling Thunder review was exhausting. Constant movement, constant performance, constant demand to be Bob Dylan, whoever that was supposed to be. He was 44 years old and tired in a way that sleep couldn’t fix.

They’d played Seattle, then Eugene, then a small town in Northern California where the venue was half empty, but Dylan had played anyway, giving the same intensity to 200 people that he’d given to 20,000. After that show, an old man had waited by the turb bus. Security tried to move him along, but the man was persistent.

I just need to give him something, the old man said, holding a worn envelope. One of the roies took it. I’ll make sure he gets it. The old man shook his head. No, I need to hand it to him. I’ve been carrying this for 30 years. Something in his voice made the roadie stop. He went to find Dylan.

Dylan came out of the bus. He looked at the old man, 70, maybe older, wearing a faded army jacket and holding that envelope like it was the most important thing in the world. You Dylan? The old man asked. Sometimes, Dylan said. The old man handed him the envelope. My son gave this to me in 1967. He was 18, about to ship out to Vietnam.

He said, “Dad, if something happens to me, make sure Bob Dylan gets this. He’ll understand.” Dylan took the envelope. What happened to your son? He came home in a box 6 months later. I’ve been carrying his letter ever since trying to get it to you. Nobody would let me near you until tonight. Dylan stood there holding the envelope, the turbus engine idling behind him, the road crew waiting to leave.

What’s your son’s name? Dylan asked quietly. Marcus. Marcus Webb. He loved your music, especially blowing in the wind. He played it on his guitar until the strings broke. Said it helped him make sense of things. Dylan nodded slowly. Thank you for bringing this to me. The old man’s eyes filled with tears. He’s been gone 30 years, but I still hear his voice sometimes. Singing your songs.

Dylan didn’t know what to say to that. So, he just stood there with the old man in the parking lot of a venue in Northern California, holding a letter from a dead soldier while the world waited for him to keep moving. When he got back on the bus, he opened the envelope. The letter was short, written in careful, young handwriting on line paper that had yellowed with age.

Mr. Dylan, I’m writing this before I ship out because I don’t know if I’m coming back. My dad thinks I’m crazy for writing to someone I’ll never meet. But I wanted you to know something. Your songs made me feel less alone. When everything got confusing, the war, the protests, my friends dying, my dad crying when he thinks I can’t hear.

Your music was the only thing that felt true. I don’t know what’s going to happen to me, but if something does, I hope someone plays blowing in the wind at my funeral and I hope you keep making music because people like me need to hear that someone else is asking the same questions. Thank you for that, Marcus Webb.

Dylan read it three times on the bus. Then he folded it carefully and put it in his jacket pocket. He didn’t tell anyone about it. He just carried it for two weeks. He carried Marcus Webb’s letter while the Rolling Thunder Review rolled through Oregon and Washington. Every night he performed. Every night he sang the songs people expected.

Every night he played Blowing in the Wind, the song he’d written when he was 21, the song that had become an anthem, the song that followed him everywhere, whether he wanted it to or not. And every night he thought about Marcus Webb, dead at 18, who had loved that song enough to request it at his own funeral.

Subscribe and leave a comment because the most important part of this story is still unfolding. Portland, the Civic Center, November 1975. Dylan stood on stage in silence. The crowd was getting restless. Some people were shouting requests. Play Blowing in the Wind. Someone yelled. Others joined in. The times they are a changing like a rolling stone.

Dylan stood motionless, the guitar hanging at his side. Backstage, the band was confused. The term manager was panicking. Is he sick? Is something wrong? Should we cancel? Joan Bayz, who was part of the review, watched from the wings. He’s making a choice, she said quietly. What choice? I don’t know yet, but he’s making it.

On stage, Dylan finally moved. He stepped toward the microphone. The crowd noise immediately dropped, everyone straining to hear. I’ve been playing Blowing in the Wind for 15 years, Dylan said, his voice rough and low. And I’m not sure I understand it any better now than I did when I wrote it. Silence. 15,000 people not knowing how to respond to that.

A few weeks ago, Dylan continued, “I got a letter from a man who died in 1967. His father’s been carrying it for 30 years, trying to get it to me. The letter said, “My songs made him feel less alone before he shipped out to Vietnam. He died there.” 18 years old. You could hear people breathing. The silence had weight now.

He loved blowing in the wind, Dylan said. Wanted it played at his funeral. And I’ve been thinking about that, about what it means to write a song when you’re young and angry and confused. And then watch that song become something you never intended. Watch it become an anthem, a protest song, a graduation song, a funeral song.

He paused, looking down at his guitar. I don’t want to play it tonight, he said simply. I’m tired of it. I’m tired of what it’s become. I’m tired of people expecting me to be the 21-year-old kid who wrote it. That kid is gone. He’s been gone for a long time. The silence was absolute now. This wasn’t what people paid for.

This wasn’t what concerts were supposed to be. Dylan lifted his head and looked out at the crowd. So, I’m not going to play anything tonight unless one of you can give me a reason. A real reason, not because you pay for a ticket, not because you want to hear the hits, but a real reason why these songs matter. The challenge hung in the air.

Away from the spotlight, Dylan made a choice no one expected. For maybe 20 seconds, nobody moved. The crowd didn’t know if this was performance art or a breakdown or something else entirely. Then, a voice came from somewhere in the middle of the venue. A woman’s voice clear and strong because my brother is in the VA hospital and he can’t walk anymore.

And the only thing that keeps him from giving up is the cassette tape of your concert from 1974 that I play for him every Sunday. Dylan turned his head toward the voice, though he couldn’t see her in the darkness beyond the lights. Silence again, then another voice from the back. Because my daughter asks me what the 60s were about and I don’t know how to explain it except to play her your songs.

Another voice younger. Because I’m 18 and everything is confusing and your music is the only thing that feels honest. An older man because my wife died last month and don’t think twice was our song and I need to hear it one more time. One by one voices from the darkness. not shouting, not demanding, just answering Dylan’s question with the raw truth of why they’d come.

Dylan stood at the microphone listening. He didn’t interrupt, didn’t respond. Just listened as 15,000 people told him, one voice at a time, why the songs mattered. A young woman near the front said, “Because you wrote what I couldn’t say.” An old veteran. Because masters of war said what I felt when I came home and nobody cared.

A teacher because I play the times. They are changing for my students every year and they finally understand that change is possible. The voices went on for 5 minutes. Then seven, then 10. A spontaneous testimony from strangers who had come to see Bob Dylan and found themselves explaining their own lives instead. Dylan listened to all of it.

His face showed nothing, but anyone who looked closely could see his jaw working could see the way he gripped the neck of his guitar a little tighter. Finally, the voices stopped. The silence that followed was different from before. It was full instead of empty. Dylan stood for another long moment. Then he lifted his guitar into playing position for the first time that night.

“All right,” he said quietly. “I’ll play.” What followed stayed with everyone who witnessed it long after the sound faded. He played for three hours. Not the plan said list, not the crowd-pleasers. He played the songs that the voices had asked for. He played don’t think twice for the man whose wife had died.

He played Masters of War for the veteran. He played the times they are a changing for the teacher. And at the end, he played blowing in the wind. But before he did, he pulled Marcus Webb’s letter from his jacket pocket. He didn’t read it aloud. He just held it up briefly so people in the front rows could see it was there. “This is for Marcus Webb,” Dylan said into the microphone.

“Who died in 1967, who loved this song, who I never met, but who taught me tonight that these songs don’t belong to me anymore. They belong to everyone who needs them. He played it slow, stripped down, no embellishment, just the song the way it was written, raw and simple, and asking questions that still didn’t have answers.

When he finished, the crowd didn’t erupt in applause. They stood in silence for several seconds. 15,000 people honoring the moment, honoring Marcus Webb, honoring whatever it was they’d all just witnessed. Then the applause came. Not wild cheering. Respectful. Grateful. Dylan set his guitar down gently and walked off stage without a word. Share and subscribe.

Some stories deserve to be remembered. Dylan never spoke publicly about that night. But people who were there never forgot it. It became one of those concerts that grows in legend. The night Bob Dylan refused to play until the audience told him why it mattered. Marcus Webb’s letter stayed in Dylan’s jacket pocket for the rest of the tour.

Then it was framed and placed in a private collection he never showed anyone. Next to it, he kept a handwritten list of every voice that spoke that night in Portland. Names he didn’t know, reasons he didn’t forget. Years later, a journalist asked Dylan about the moment he almost didn’t play a concert. Dylan didn’t answer directly.

He just said, “Sometimes you need to be reminded why you started.” The woman whose brother was in the VA hospital sent Dylan a letter months later. Her brother had died, but he’d heard about the Portland concert. It gave him peace, she wrote. Knowing his story mattered to someone, Dylan wrote back two sentences. Your brother’s story mattered. So did yours.

That night changed how Dylan approached every concert after. He stopped trying to escape the songs. He let them belong to the people who needed them. The guitar he held that night, the one that hung silent while 15,000 voices spoke, sits in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame today.

A small plaque beside it reads, “Used but not played. Portland, 1975.