Bob Dylan didn’t accept the challenge, but he couldn’t ignore it either. He returned to his hotel room, picked up his guitar, and wrote until dawn. Then he put the notebook in a drawer, and never opened it again. Portland, Oregon, November 1987. The tour had been grinding on for 6 weeks.

small venues, midsize theaters, the kind of rooms where Dylan could see every face in the audience and they could see every line in his. He was 46 years old. The critics had been saying he was finished for a decade now, past his prime, living on legacy, the voice of a generation who stopped listening to himself. Dylan didn’t read reviews anymore, but people made sure he heard them anyway.

The show that night had been fine. Not transcendent, not terrible, fine. He played the songs they wanted to hear. He played some they didn’t. The audience had applauded politely. Some had left early. After the show, Dylan was in the small backstage area. Really just a converted storage room with a couch, a mirror, and bad lighting.

He was putting his guitar in its case when someone knocked. Bob, there’s a gentleman asking to see you. Says he’s from Rolling Stone. Dylan didn’t look up. Tell him I don’t do interviews after shows. He says he just wants 5 minutes. Says you knew each other in ‘ 65. Dylan’s hands paused on the guitar case latches. 1965, the year everything changed.

The year he went electric. The year half his fans called him a traitor and the other half called him a prophet. What’s his name? Marcus Greenfield. Dylan remembered the young critic who’ written that he was betraying the folk movement. The one who had stood up at a press conference and demanded Dylan explain himself. Dylan had looked at him, said nothing, and walked out. 22 years ago.

Give me a minute, Dylan said. Marcus Greenfield looked older, graying, thicker around the middle, wearing glasses now, but the same intensity in his eyes, that mixture of admiration and disappointment that Dylan had seen in so many faces over the years. Bob, Marcus said, extending his hand. Thanks for seeing me.

Dylan shook it briefly. Said nothing, waited. I won’t take much of your time. I just I wanted to ask you something. I’m writing a piece about artistic legacy, about what happens when the revolutionary becomes the establishment. Dylan leaned against the wall, arms crossed, still said nothing. Marcus took a breath.

Do you think you’ve written anything truly honest in the last 10 years, or are you just performing the memory of who you used to be? The question hung in the air from somewhere down the hall. They could hear the venue staff breaking down equipment, metal clanging, voices calling to each other.

Dylan looked at Marcus for a long moment. Then he picked up his guitar case and walked toward the door. “Bob, I didn’t mean.” “You did,” Dylan said quietly, not turning around. “And maybe you’re right.” He walked out. Didn’t slam the door. just left it open behind him. Dylan didn’t explain himself. He never did. The hotel was three blocks from the venue. Dylan walked.

His road manager had a car waiting, but Dylan waved him off. He needed the air, the cold, the space between the performance and whatever came next. The Paramount Hotel, 12 floors, built in the 1920s. The kind of place that had been elegant once and was now just holding on. Dylan’s room was on the eighth floor, corner room, window facing the street.

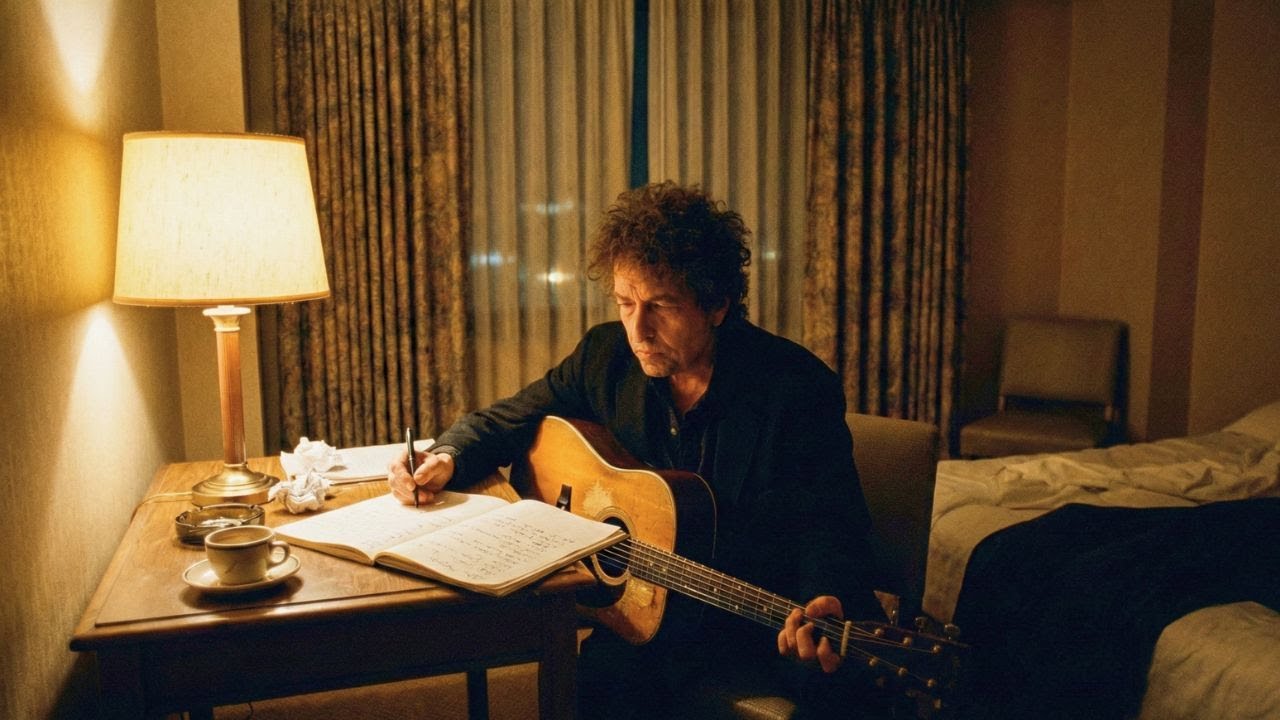

He unlocked the door, set his guitar case down, and stood in the dark for a moment. The room smelled like old carpet and someone else’s cigarettes. The bed was made, but he wouldn’t sleep. He never slept after shows. Too much electricity still running through him. Dylan turned on the desk lamp. Weak yellow light.

He sat down heavily in the wooden chair, pulled the guitar out of its case, and held it across his lap. The question was still there, sitting in the room with him. Do you think you’ve written anything truly honest in the last 10 years? He thought about the albums, the songs, the words he put together because words were what people expected from him.

Some of them were good, some of them were true, but were they honest? Was there a difference? Dylan looked at the notepad on the desk. Hotel stationary. The Paramount Hotel printed at the top and faded script. He picked up the pen sitting beside it. He didn’t plan to write. didn’t sit down thinking he’d prove anything to Marcus Greenfield or to himself, but his hand moved anyway.

First line, then second, the guitar across his lap, fingers finding cords without thinking about them. The coffee from the venue was still sitting in a paper cup on the nightstand. He drank it cold, didn’t taste it, just needed something to do with his hands when they weren’t writing or playing. Subscribe and leave a comment because the most important part of this story is still unfolding.

Outside the window, Portland was getting quieter. 2:00 a.m. became 3. Three became 4, Dylan wrote. Not the careful construction he learned to do. Not the word play and the masks and the mythology. Just what was underneath. The weight of being the person everyone wanted him to be. The loneliness of stages and hotel rooms. The years stacking up.

The friends gone. The marriages failed. The children who didn’t quite know him. The verse about seeing his own face on magazine covers and not recognizing it. The chorus about singing other people’s memories of who he used to be. The bridge about the kid from Hibbing, Minnesota who had wanted to play music and ended up becoming a symbol.

His handwriting got worse as the hours passed. the letters slanting, cramping, but he kept going. The guitar playing got quieter, too. Barely strummed, just enough to hear the changes, to feel where the melody wanted to go. At some point, he realized he was crying, not sobbing, just tears running down his face and dripping onto the notepad, smudging the ink.

He didn’t stop writing. When the first light started coming through the window, that gray pre-dawn light that makes everything look temporary, Dylan put down the pen. He looked at what he’d written. Six pages front and back. A complete song. Maybe the most complete song he’d written in a decade. Every word true.

Every line stripped of the armor he’d learned to wear. And he knew, looking at it, that he would never play it for anyone. This wasn’t for an audience. This wasn’t even for him, really. It was just what had needed to come out. What Marcus Greenfield’s question had unlocked. The honest answer Dylan couldn’t speak out loud, but could write in a hotel room at 4 in the morning when no one was watching.

He closed the notebook, stood up slowly, his back stiff from sitting hunched over for hours. He walked to his suitcase, opened the inner pocket, and put the notebook inside, zipped it shut. The guitar went back in its case. Dylan lay down on top of the maid bed, still fully dressed, and watched the ceiling get lighter as dawn came. Away from the spotlight, Dylan made a choice no one expected.

The tour continued Portland to Seattle, Seattle to Vancouver, Vancouver to Spokane, city after city, show after show. Dylan performed, the audiences applauded, the critics wrote their reviews. Marcus Greenfield’s article came out 2 months later. The Revolutionary at Sunset, Bob Dylan, and The Art of Repetition.

It was thoughtful, fair, even. It noted Dylan’s inconsistency, his tendency to coast on legacy, his occasional flashes of brilliance that felt like echoes of something greater. Dylan didn’t read it, but people told him about it. He never mentioned the hotel room, never told anyone about the six-page song written in one night in Portland.

The notebook stayed in his suitcase, then moved to a drawer in his home studio, then to a box in storage. Years passed. Dylan kept touring, kept recording. Some albums were better than others. Some songs connected, some didn’t. Critics continued to debate whether he was still relevant, still vital, still Dylan.

And through all of it, that notebook sat unopened. In 1997, 10 years after Portland, Dylan was going through old storage boxes looking for something else. A photograph, some sheet music. He couldn’t remember what. His hands found the notebook instead. He sat on the floor of the storage room and read what he’d written that night. The raw, unguarded truth of a 46-year-old man confronting the weight of his own mythology.

It was still honest. Maybe more honest now with 10 more years of distance. Dylan’s manager walked in, found him sitting there with the notebook open. What’s that? Dylan closed it. something old. New album material. No. You sure? We could use. I’m sure. He put the notebook back in the box. Closed the lid. What followed stayed with everyone who witnessed it.

Long after the sound faded. Marcus Greenfield died in 2003. Heart attack. Sudden. He was 61. Dylan heard about it through mutual friends. He didn’t go to the funeral. Sent flowers instead. The card said simply, “You asked the right question. B.” Marcus’s family didn’t know what that meant. Neither did most people.

But Dylan knew. The notebook is still in that storage box. Dylan has never performed that song, never recorded it, never played it for anyone. in interviews, the rare ones he gives. When people ask if he has unreleased material, unfinished work, songs that never saw the light, Dylan just shrugs. Everybody’s got notebooks full of things that weren’t meant to be shared.

But if they’re good, shouldn’t people hear them? Maybe some things are good because people don’t hear them. The interviewer usually looks confused. Dylan doesn’t elaborate. He never does. Share and subscribe. Some stories deserve to be remembered. In 2016, Dylan won the Nobel Prize for Literature.

The committee cited his profound impact on popular music, his poetry, his enduring influence on culture. He didn’t attend the ceremony. Someone asked him later if winning validated his life’s work. I don’t need validation, Dylan said. I write because that’s what I do. Sometimes what comes out is for other people. Sometimes it’s just for me.

Is that enough? Dylan looked out the window, quiet for a long moment. It has to be. The notebook still sits in storage. Maybe his children will find it someday. Maybe it’ll be donated to an archive. Maybe it’ll just disappear, lost in the endless accumulation of a long life lived publicly. But that night in Portland, November 1987, when Bob Dylan sat alone in a hotel room and wrote the most honest thing he’d written in years, and then chose to keep it for himself. That night mattered.

Not because anyone heard the song, but because Dylan proved to himself that he could still write Truth, even if Truth didn’t need an audience. Marcus Greenfield asked if Dylan had written anything honest in 10 years. The answer was yes. But honesty, Dylan learned that night doesn’t always need to be performed.

Sometimes the most authentic thing you can do is create something and then let it rest in darkness. Known only to you, preserved not for history, but for the simple act of having been true. The notebook remains closed. And that somehow is the most Dylan thing of all. There’s a recording studio in New York where Dylan sometimes works. The engineers who’ve been there long enough know not to ask questions.

They know Dylan arrives with what he wants to record and leaves when it’s done. No explanations, no stories about where the songs came from. But one engineer, a man named Thomas, who’d worked with Dylan since the mid ’90s, once asked him about process, about how Dylan knew when a song was finished versus when it was private.

Dylan was tuning his guitar. Didn’t look up. You feel it? He said finally. Some songs want to be heard. They push at you until you let them out. Other songs. He paused, tightened a string. Other songs are like letters you write but don’t send. The writing matters, not the sending.

Thomas nodded, though he didn’t fully understand. The song in Portland, Dylan said so quietly. Thomas almost missed it. That was a letter I wrote to myself 30ome years ago now. Still haven’t sent it. Will you ever? Dylan’s fingers moved across the frets, playing something soft and minor. A melody Thomas had never heard. No, Dylan said. That’s the point.

He played the melody again, then stopped. Let’s record something else today. And they did. The Portland song, if you can call it that, a song no one’s ever heard, lives in a cardboard box in a climate controlled storage facility somewhere in California. Next to it are dozens of other notebooks, other scraps, other fragments of a life spent putting words to music.

Some will be discovered, some won’t. Bob Dylan, now in his 80s, still tours, still writes, still guards his privacy with the same fierce silence he’s maintained for six decades. And somewhere in that storage facility, six pages of handwritten lyrics contain the answer to Marcus Greenfield’s question. Do you think you’ve written anything truly honest in the last 10 years? Yes.

But honesty doesn’t owe anyone an audience. That notebook proves it.