The rattlesnake coiled 5 in from Dean Martin’s boot when John Wayne froze. The cameras were about to roll. The director was raising his hand to call action. And Dean hadn’t noticed a thing. Look, because what Wayne did in the next two seconds didn’t just save Dean’s life. It turned into an agreement between two men that neither spoke about for 10 years.

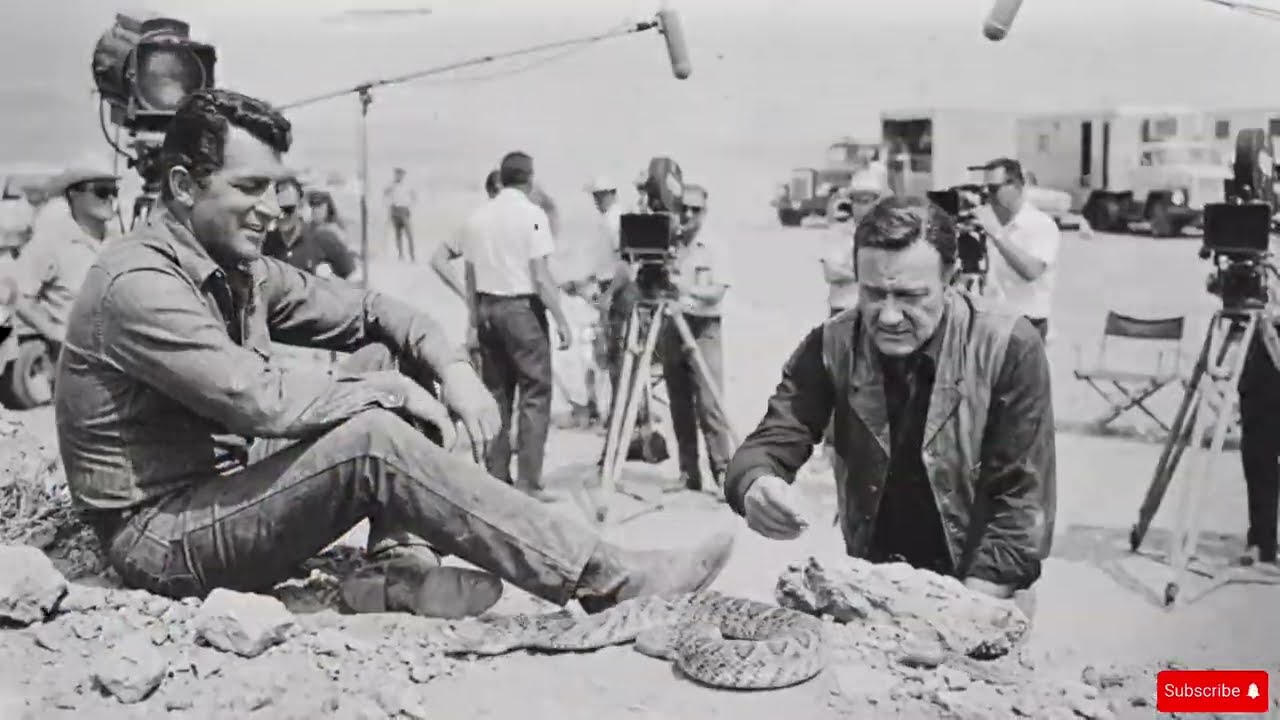

And almost nobody understood what it cost both of them. It was April 1968 and the Arizona desert stretched out like a cracked skillet under a sun that didn’t forgive mistakes. The production was called Rio Fuego, a big budget western that had already burned through two weeks of shooting and half a million dollars.

Dean Martin and John Wayne weren’t supposed to be on the same set. Dean was contracted for 3 weeks, Wayne for two, but the studio had shuffled the schedule after a sandstorm wiped out an entire week. Now they were here together, two icons in the middle of nowhere, surrounded by a crew of 60 and a director who kept checking his watch like it owed him money.

Dean was playing a card sharp turned reluctant sheriff. Wayne, a retired marshall with a past nobody talked about. The scene they were setting up was simple on paper. Two men at a desert camp cooking beans over a fire talking about the gang that was coming. The kind of scene that looked easy until you factored in the heat, the dust, the temperamental horses tied 20 feet away, and the fact that neither man had slept more than four hours the night before.

Notice how nobody mentions the other thing they were dealing with. The tension that had been building since day one. Dean and Wayne respected each other, sure, but respect doesn’t mean you work the same way. Dean like to keep things loose, crack jokes between takes, find the character in the moment. Wayne preferred discipline, hitting marks, getting it right the first time.

For two weeks, they’d been dancing around each other’s styles, polite but careful, like two dogs circling in a yard that’s just a little too small. The morning had started with the usual chaos. Makeup at 5, wardrobe at 6, Dean’s hat didn’t fit right, so they had to steam it again. Wayne’s horse threw a shoe, and they had to wait 40 minutes for the Wrangler to fix it.

By the time they got to the desert location, 15 miles out from base camp, nothing but sand and scrub and rocks that looked like they’d been there since God got bored, it was already 93° and the crew was moving slow. The campfire scene was supposed to be a one-take wonder. The director, a lean man named Garrett, who’d done four westerns and thought he’d seen everything, wanted it natural and unpolished.

“Just talk like you’re two old men who’ve known each other forever,” he’d said. “Don’t act it, be it.” Dean had grinned at that. Wayne had just nodded and checked his rifle prop for the fifth time. They’d done a walk through 30 minutes earlier. Dean’s position, left side of the fire, sitting on a saddle blanket, tin cup in hand. Wayne’s position, right side standing, one boot up on a rock, looking out toward the horizon like he expected trouble.

Between them, the fire, fake logs rigged with propane, controlled by a guy with a remote 40 ft away. Behind them, two cameras on dollies, a boom mic just out of frame, and Garrett watching every move like a hawk. Wait, because this is where the day split in half, where everything that came before stopped mattering, and everything after became the only story that counted.

They reset for the real take. Dean settled onto the blanket, rolled his shoulders, adjusted his hat. Wayne took his position by the rock, shifted his weight, scanned the horizon. The script supervisor called out the scene number. The sound guy clapped the slate. Garrett raised his hand, ready to call action. That’s when Wayne saw it.

Not right away. That’s the thing nobody understands. He didn’t see the snake first. What he saw was a flicker of movement in his peripheral vision. Just a shadow shifting in the sand about 3 ft from Dean’s right boot. For half a second, Wayne thought it was a piece of tumble weed. Or maybe a lizard. The desert was full of both.

But something in the way it moved made his gut tighten, made his eyes snap to the spot even as Garrett’s mouth was opening to shout action. The snake was coiled in a tight spiral, dusty brown with diamond patterns that blended almost perfectly with the sand. Its head was raised maybe 4 in, tongue flicking, tail rattling so quietly that the sound didn’t carry over the wind in the crew noise.

It was a western diamond back, probably 3 ft long, and it was less than 6 in from Dean’s boot heel. Wayne’s whole body locked. Not in fear. Wayne didn’t freeze from fear, but in calculation. His brain was doing math faster than he’d ever done it. Dean hadn’t seen the snake, wasn’t looking down, was focused on his line delivery.

The cameras were about to roll. The crew was spread out. Closest person maybe 15 ft away. If Wayne shouted, Dean would jerk, might pull his leg back fast, and the snake would strike. If Wayne moved toward Dean, same problem. Sudden motion, the snake strikes. If he did nothing, Dean might shift his weight any second, press down on that boot, and the snake would bury fangs through leather and denim before anyone could blink.

Two seconds to decide, maybe less. Listen to what happened next, because this is where you see who these men really were when the performance stopped. Wayne didn’t shout, didn’t move toward Dean. Instead, he did something so precise and so strange that half the crew didn’t even register it until later.

He lifted his right hand, the one that wasn’t holding the prop rifle, and raised it slowly, palm out, fingers spread, not pointing at Dean, not waving, just up like a man stopping traffic. At the same time, he shifted his eyes, locked them onto Dean’s face with an intensity that cut through the desert heat like a blade.

He didn’t say a word, didn’t make a sound, just that hand, just that look. Dean caught it immediately. You don’t spend 20 years performing live without learning to read a room. And Dean could read Wayne’s face like a telegram. Something in Wayne’s expression, the absolute stillness, the focus, the way his jaw was set, made Dean’s whole body go quiet.

He didn’t know what was wrong, but he knew something was. He froze mid breath, cup halfway to his mouth, eyes locked on Wayne’s. Don’t move. Wayne’s voice was barely above a whisper, but it carried the weight of a command. Flat, calm, final. Dean’s eyes flicked down for just a fraction of a second. instinct wanting to check what was wrong, but Wayne’s voice cut through again.

Eyes on me, Dean. Don’t look down. The set had gone quiet. Garrett had lowered his hand, confusion spreading across his face. The cameramen were glancing at each other. The script supervisor started to say something, but stopped when she saw Wayne’s expression. “There’s a snake,” Wayne said, still in that same low, even tone. “Right side, your boot.

Don’t move anything.” Dean’s face didn’t change. That was the thing that stuck with everyone who was there. Dean didn’t panic, didn’t gasp, didn’t even blink hard. His fingers tightened just slightly on the tin cup. That was all. He kept his eyes on Wayne and waited. Remember this moment because what you’re watching isn’t acting.

This is two men in the same crisis. No script, no safety net, and only one of them can see the threat. Wayne started moving. Not fast. Fast would spook the snake. Slow, deliberate. He lowered the prop rifle to the sand without a sound, then took one step to his left, angling so he could approach the snake from behind Dean from the side where the reptile’s attention wasn’t focused.

Every person on that set was holding their breath. The boom operator later said he could hear his own heartbeat in his headphones. The snake’s rattle picked up tempo, a dry whisper that finally became audible over the wind. Now the crew could hear it. Now they understood. Someone gasped. Garrett put his hand up, signaling everyone to stay still and stay quiet.

Wayne took another step, then another. He was maybe 8 ft from Dean now, coming in at an angle. His eyes never left the snake. Later, he’d tell people he was running scenarios. If it struck before he got there, could he grab Dean’s leg and pull him back fast enough? If it struck and hit, how long did they have before the venom started shutting things down? Where was the nearest hospital? 40 mi. helicopter.

Maybe 30 minutes if they could even get a signal out here. Dean’s voice came out quiet, conversational like they were still in the scene. How big? Big enough. How close? Too close. Can you get it? Wayne didn’t answer that one. Instead, he took one more step. Close enough now that he could see the snake’s scales, the pattern of its markings, the way its body was tensed.

He looked around fast. No stick, no prop gun that was actually useful. nothing but sand and rocks. His right hand went to his belt where a knife sat in a leather sheath. Prop knife, dull blade, useless. Stop for a second and understand what Wayne was calculating here. He could try to kill the snake, but if he missed or if the knife didn’t go deep enough on the first strike, the snake would retaliate instantly, and Dean’s leg was right there.

He could try to scare it away, but rattlesnakes don’t scare easy. And a threatened snake is more dangerous than a calm one. He could wait it out, hope the snake lost interest, and slithered away. But that could take minutes or hours, and Dean couldn’t stay frozen forever in this heat. Wayne made his choice. He moved in a way that nobody expected.

Instead of going for the snake, he stepped directly between Dean and the reptile, putting his own leg in the strike zone. Then he bent down slow, hands open and empty, and started making a low hissing sound. Not loud, just a steady that matched the snake’s rattle rhythm. The crew watched in stunned silence as Wayne lowered himself into a crouch.

Still hissing, still moving with that same impossible slowness. The snake’s head tracked him, shifted focus from Dean’s boot to Wayne’s boot. Wayne kept hissing, kept moving in micro increments, drawing the snake’s attention fully onto himself. Then he did something that made Garrett later say he’d never seen anything like it in 40 years of film making.

Wayne reached down, grabbed a handful of sand, and in one smooth motion, tossed it in a low arc. Not at the snake, but past it, landing in the brush 3 ft behind the reptile. The snake’s head whipped toward the sound. Instinct, just for a second. That second was all Wayne needed. He grabbed Dean’s arm and pulled him backward in one hard yank.

Both men tumbling away from the campfire setup and landing in the sand 10 ft clear. The snake struck at empty air where Dean’s boot had been, then coiled again, rattling louder now, angry. Three crew members rushed in with long poles and blankets, coring the snake away from the set.

The wrangler, who apparently knew how to handle reptiles, got it into a canvas bag within 90 seconds. The whole crisis, start to finish, had lasted maybe 4 minutes. Dean sat in the sand, breathing hard for the first time, his hands shaking slightly as adrenaline finally caught up with his nervous system. Wayne stood over him, still watching the spot where the snake had been, like he expected another one to show up. “You good?” Wayne asked.

Dean looked up at him, squinting against the sun. “Yeah, yeah, I’m good.” “You sure, Duke? I’m sure.” Wayne nodded once, then reached down and pulled Dean to his feet. For a moment, they just stood there, two men in dusty western costumes, while the crew buzzed around them, checking for more snakes and arguing about whether they should shut down for the day.

Notice what didn’t happen. No big speech, no dramatic embrace, no moment where they talked about what it meant. They just dusted themselves off and waited while Garrett decided what to do next. What you need to understand about the rest of that day is how carefully both men acted like nothing had changed. They shot the scene 2 hours later after the area had been swept three times.

They got it in two takes. They wrapped for the day, went back to base camp, ate dinner in the communal tent with the crew. Dean made jokes about snake boots. Wayne talked to the stunt coordinator about tomorrow’s horse sequence. Nobody watching would have guessed that anything unusual had happened. But look closer. Watch how Dean’s eyes tracked Wayne for the rest of the shoot.

How when they set up for the next scene, Dean checked his positions twice, but if Wayne gave him a nod, he relaxed. Watch how Wayne started standing just a little closer during setups, not hovering, just present. How when they broke for lunch, they sat at the same table without discussing it, something they hadn’t done before. The agreement nobody talked about started that afternoon.

Dean never mentioned the snake to the press. Wayne never told the story in interviews. When reporters asked about working together, they said professional things about respect and craft. The crew knew better than to gossip. Wayne had a reputation and you didn’t cross it. The studio wanted the story buried because insurance and liability, so everyone signed NDAs that covered onset incidents.

But the agreement between Dean and Wayne went deeper than silence. It was something about trust that neither man had words for. Dean had frozen when Wayne told him to freeze. Had kept his eyes up when his instinct screamed to look down. Had trusted Wayne’s voice in a moment when his life depended on it.

And Wayne had stepped between Dean and the snake. Had put his own leg in the strike zone. Had made himself the target. That kind of thing changes the math between two people. Remember the tension from earlier? The different working styles, the careful distance. It evaporated. Not into friendship. Exactly. These weren’t men who did backyard barbecues and phone calls on birthdays, but into something harder and cleaner.

Respect that had been tested, trust that had been proven. They finished the movie 3 days ahead of schedule. The chemistry in their scenes together became the thing critics talked about most when Rio Fuego came out that fall. For 10 years, neither man spoke publicly about the snake. Then in 1978, during a tribute event for Wayne after his cancer diagnosis, Dean was asked to say a few words.

He kept it short like he always did, but at the end he told one story about a day in the desert when Wayne saved his life with a handful of sand and a hiss. Wayne was in the audience that night, thin from treatment, but still upright. When Dean finished, Wayne just raised his glass an inch, the smallest salute. Dean raised his back. That was all.

Everyone else in the room was crying or applauding, but those two men just held that moment between them, quiet and complete. The snake, by the way, was relocated 20 m from the film location and released unharmed. The wrangler who handled it said it was a female, probably guarding a nest somewhere nearby, which explained why it had been so aggressive, just doing what snakes do, protecting what mattered.

Here’s what stays with you about that desert afternoon. It wasn’t about heroism in the Hollywood sense. Wayne didn’t dive in front of a bullet or fight off 10 men. He made a series of small, precise choices under pressure. Each one calculated to keep his friend alive. And Dean made one choice, to trust Wayne completely in a moment when instinct said panic.

That’s the real story. Not the snake, not the drama, but the fact that when it mattered, two professionals who barely knew each other became two men who’d go through hell together if the script called for it. If you enjoyed spending this time here, I’d be grateful if you’d consider subscribing. A simple like also helps more than you’d think.

And if you want to know what really happened the night Wayne showed up at Dean’s Vegas show three years later and returned the favor in a way nobody saw coming, tell me in the comments.