A desk phone screams in the dark. Once, twice, then stops like someone on the other end is listening. A map case snaps open. Poland corridors, rail lines, red pencil marks too fresh to trust. A clark’s hand shakes as he presses a seal into hot wax. Another hand, older, crushes a cigarette without lighting it.

Papers slide across the table. Not plans, not orders. A technical report stamped Gahima Reicha. The ink still smells wet. In the corner, a date, a deadline, a line underlined so hard the page has torn. Across the room, a general clears his throat and no one looks at him because they all know what he’s about to say. Not ready.

Not the engines, not the rockets, not the skies. Silence hits like a blow. Then the door opens. boots, a coat brush, a quiet cough from the agitant, and the man they’ve been stalling for steps in, eyes fixed on the folder. He doesn’t ask what it is. He already knows. He only asks one thing.

How long? And the answer makes the room go cold. Berlin, Reich, Chancellory, late August 1939. In a cramped operations room lined with maps and thick with cigarette smoke, Field Marshall Wilhelm Kitle stands rigid beside General Alfred Yodel. Behind them, Colonel General Walter Fonraich and General France Halder hover over a table scattered with root arrows and snapped pencils.

An agitant has just delivered a sealed folder, heavy stockp, red wax marked nerd infura. Inside a memorandum from the weapons offices and air staff, development schedules, test failures, production shortfalls, and one blunt sentence about earliest operational readiness that no one in the room wants to read aloud.

Halder doesn’t argue with politics, he argues with time. He taps the underlined line once, then pulls his hand back as if it burned him. Kitle whispers that the folder must reach Hitler before the next conference. Yodel glances at the telephone log. Three calls already waiting, all unanswered. The door handle turns.

Boots stop at the threshold. Adolf Hitler enters. He points at the folder and says almost calmly, “How long?” Halddera clears his throat. The Luftvafer’s next generation of heavy bombers won’t fly for another 2 years. The Navy’s new submarine fleet is 18 months behind schedule. The army’s panza divisions are still equipped with training tanks, light vehicles never meant to face real armor.

The rockets are nothing but sketches and explosion craters. The jets exist only in wind tunnels and the dreams of engineers. If Germany goes to war now, she goes to war with what she has, not what she was promised. Hitler listens. He does not interrupt. When Hder finishes, there is a pause so long that Kitle shifts his weight from one foot to the other.

Then Hitler speaks again. [clears throat] And if we wait, no one answers. Because everyone in that room knows the real question isn’t about weapons. It’s about something far more dangerous. It’s about whether Adolf Hitler, the man who rebuilt Germany, still believes he can outrun time itself.

This is the story of why he tried. The year is 1933. And Adolf Hitler has just become Chancellor of Germany. He inherits a nation humiliated by the Treaty of Versailles. Stripped of its military power and forbidden from developing the weapons that define modern warfare. The German army is limited to 100,000 men. The Air Force doesn’t exist, not officially.

The Navy is a ghost of its former self. And yet, within weeks of taking office, Hitler begins speaking privately about rearmament on a scale that makes his generals nervous. Not because they oppose it. They’ve dreamed of rebuilding German military might for years. What frightens them is the timeline. Hitler doesn’t talk about rearming Germany over the next decade.

He talks about doing it in four years, maybe five. He wants an air force that can darken the skies over Europe. A navy capable of challenging Britain. [clears throat] An army so powerful that no nation alone or in alliance would dare stand against it. And he wants all of it before anyone can stop him.

But here’s what Hitler doesn’t fully understand or perhaps doesn’t care to understand. Building a modern military isn’t just about ambition. It’s about steel, fuel, factories, engineers, training programs, supply chains that stretch across continents. It’s about time. And time, more than any treaty or foreign power, is the one enemy Hitler cannot simply outmaneuver.

In the months after Hitler takes power, Germany begins rearming in secret. Factories that officially produce tractors start turning out tank chassis. Glider clubs become training grounds for future fighter pilots. Shipyards work double shifts on vessels whose true purpose is carefully disguised. The world watches, suspicious but uncertain.

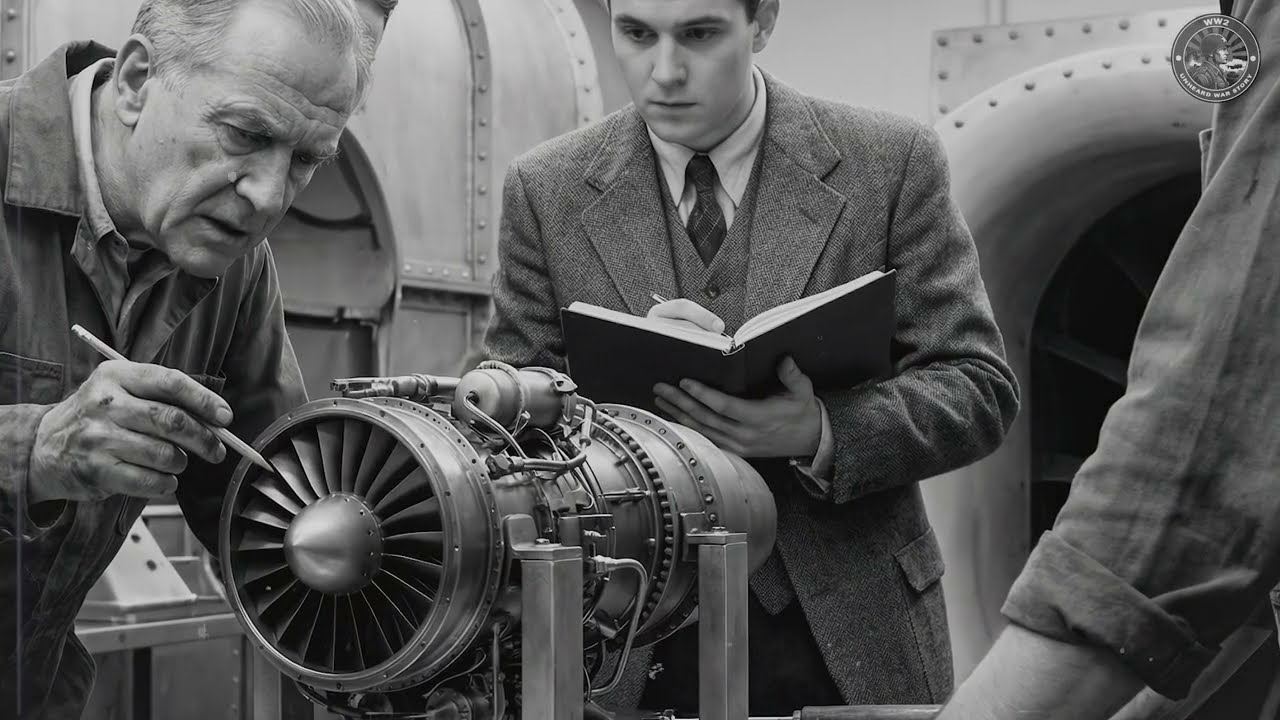

[clears throat] And for a while, the bluff holds. But behind the propaganda and the parades, the men who actually run Germany’s military know the truth. The new weapons Hitler demands aren’t just expensive. They’re revolutionary. and revolutionary technology doesn’tfollow political schedules. Consider the Luftvafer, the air force that Herman Guring promises will be the most powerful in Europe.

By 1935, it officially exists, unveiled to a shocked world that had believed Germany incapable of such a feat. But what the world sees and what the Luftvafa actually possesses are two very different things. The planes on display are impressive. The factories producing them are not. Production bottlenecks, design flaws, and a chronic shortage of trained pilots mean that the Luftvafer is years away from the force Guring describes in his speeches.

And the truly advanced aircraft, the heavy bombers, the jet engines, the long range fighters that could strike deep into enemy territory exist only on drawing boards. The same pattern repeats across every branch of the military. The Navy’s submarine fleet is growing, but the revolutionary new designs that could dominate the Atlantic are still being tested.

The Army’s Panza divisions look formidable in photographs, but many of their tanks are obsolete models, underpowered and underarmour. And the secret weapons programs, the rockets, the guided missiles, the experimental aircraft that would later terrify the allies are consuming enormous resources while producing nothing but prototypes and promises.

Now, here’s where the story takes a turn that most people don’t expect. Because while Hitler is demanding faster rearmament, some of his own generals are quietly pushing back. Not because they oppose war, not because they have moral objections to conquest, but because they understand something Hitler refuses to accept. Germany is not ready.

The man who voices this concern most clearly is General Ludvig Beck, chief of the German general staff. Beck is old school, Prussian, methodical. He believes in planning, preparation, and patience. And by 1938, he has seen enough to know that Hitler’s timeline is a recipe for disaster. Beck’s analysis is simple. Germany’s military buildup is impressive, but it is incomplete.

The weapons programs that Hitler counts on will not be ready for years. The economy is already straining under the weight of rearmament. And if Germany goes to war before these problems are solved, she will face enemies who can outproduce her, outman her, and outlast her. Beck doesn’t oppose expansion.

He opposes premature expansion. He believes Germany should wait 5 years, perhaps 10, until the wonder weapons are real, until the factories are running at full capacity, until the military is truly invincible. But Hitler has no patience for such caution. He [clears throat] has already achieved what seemed impossible.

The remilitarization of the Rhineland, the annexation of Austria, the bloodless conquest of Czechoslovakia. Each time his generals warned him of disaster, each time he ignored them, and each time he was right. The pattern has made him contemptuous of professional military advice. He sees Beck’s warnings not as wisdom, but as weakness, as fear dressed up in technical language.

In August 1938, Beck resigns. He cannot in good conscience serve a leader who refuses to listen. His departure sends a ripple of unease through the officer core. But it changes nothing. Hitler replaces him with France Halder, a man who shares many of Beck’s doubts but lacks his willingness to act on them. And the march toward war continues.

What Beck understood, what all the generals understood was that Hitler’s gamble rested on a single terrifying assumption that the next war would be short. That Germany could strike fast, win decisively, and consolidate her gains before her enemies could mobilize their full strength. If that assumption proved wrong, if the war dragged on, if it became a grinding contest of industrial might and national endurance, Germany would lose.

She would lose because she had started too soon. Because the wonder weapons weren’t ready. Let’s talk about those weapons. Because the phrase wonder weapons isn’t propaganda. It’s an accurate description of what German engineers were actually developing in the late 1930s. Technology so advanced that had they been ready in time, they might have changed the course of history.

Start with the jets. By 1939, German scientists are further along in jet propulsion than anyone else in the world. The Hankl her 178, the world’s first true jet aircraft, will fly just days after the invasion of Poland begins. But it’s a prototype, a proof of concept, not a weapon. The jet fighters that could outpace any Allied plane, the Mesashmmit Mi262, the Hanklh280 are still years away from production.

When they finally enter service in 1944, Allied pilots will describe them as terrifying, faster than anything they’ve ever seen, almost impossible to intercept. But by then, it will be too late. There will be too few jets, too little fuel, and too many Allied bombers already filling the skies over Germany. Then there are the rockets.

In a secret facility on the Baltic coast, a youngengineer named Vereron Brown is working on something unprecedented. A liquidfueled rocket capable of traveling hundreds of miles and striking targets with no warning. This will eventually become the V2, the world’s first ballistic missile. But in 1939, the program is plagued by failures.

Rockets explode on launchpads. Guidance systems malfunction. The engineering challenges are immense, and the solutions are years away. When the V2 finally rains down on London in 1944, it will kill thousands and terrorize millions. But it will not change the outcome of the war. It will arrive too late, in too small numbers, with too little accuracy.

The submarines tell a similar story. Germany’s yubot fleet is growing. But the revolutionary type Vawwine submarine, faster underwater than on the surface, capable of staying submerged for days, nearly undetectable by Allied sonar, won’t be ready until 1945. By then, the Battle of the Atlantic will already be lost.

And the tanks, the Panza 4, Germany’s main battle tank in 1939, is a capable machine. But it’s not the legendary Tiger or Panther that will later terrify Allied tank crews. Those designs are still being developed. The steel that will make their armor impenetrable. The guns that will punch through enemy vehicles at 1,000 m.

These exist only in engineering specifications and factory plans. This is what the generals tried to tell Hitler in that cramped room in August 1939. This is what the memorandum in the sealed folder made brutally clear. Germany has an impressive military. But it is not the invincible force that propaganda claims.

It is a military in transition, halfway between the old and the new. Equipped with weapons that are good enough for a short war, but inadequate for a long one. And Hitler knows it. He has seen the reports. He has heard the warnings. He understands at some level that his generals are not lying to him. So why does he give the order to attack anyway? The answer lies in a calculation that only Hitler could make.

Because Hitler isn’t just a military strategist. He’s a gambler and he’s looking at the board from a completely different angle. Here’s what Hitler sees. Yes, Germany isn’t ready, but neither are her enemies. France has a large army, but it’s built for defense, not offense. Its generals are still fighting the last war, obsessed with fortifications and static lines.

Britain has a powerful navy, but a tiny army and an air force that’s only beginning to modernize. The Soviet Union is a giant, but Stalin’s purges have gutted the Red Army’s officer corps. And the United States is an ocean away, isolationist and unlikely to intervene. If Hitler waits 5 years for the wonder weapons, what happens? Britain rearms.

France modernizes. America wakes up. The Soviet Union recovers. The window of opportunity. The brief moment when Germany is stronger relative to her enemies than she will ever be again. Closes forever. But there’s something else driving Hitler, something more dangerous than strategic calculation. It’s his own mortality.

Hitler is 50 years old in 1939. He has suffered from chronic stomach problems, insomnia, and a growing dependence on medications that cloud his judgment. He genuinely believes that he is the only man who can lead Germany to greatness. and he fears that if he waits too long, he will not live to see his vision fulfilled.

The generals talk about readiness in terms of factories and prototypes. Hitler thinks about readiness in terms of his own lifespan. He cannot afford to wait. He must act now while he still can. And then there’s the Hitler Stalin pact. In August 1939, just days before the invasion of Poland, Germany and the Soviet Union sign a non-aggression agreement that shocks the world.

Suddenly, Hitler no longer faces a two-front war. The nightmare that destroyed Germany in 1918. The crushing weight of enemies on both sides seems to have vanished. Poland is isolated. Britain and France are far away. and Stalin has agreed to divide Eastern Europe with Hitler, giving Germany a free hand to strike West without worrying about the East.

This changes everything. The pact is a diplomatic master stroke, a temporary alliance between ideological enemies that buys Hitler exactly what he needs. Time to conquer Western Europe before turning east. He can defeat Poland in weeks. He can smash France before the British can fully mobilize. And then with Europe under his control, he can finish building the wonder weapons at leisure.

He can wait for the jets and the rockets and the super submarines. Not before the war, but during it. It’s a gamble, a colossal world historical gamble. And Hitler takes it. September 1st, 1939. At 4:45 in the morning, German forces cross the Polish border. The Luftvafa strikes airfields and communication centers.

Panza divisions surge forward, cutting through Polish defenses with a speed that stuns observers around the world. This is Blitzkrieg, lightning war, fast, overwhelming, terrifying, and for a fewweeks, it seems to prove Hitler right. Poland falls in just over a month. The speed of the victory is so stunning that it obscures the problem simmering beneath the surface.

Tanks break down at alarming rates. Supply lines stretch and snap. The Luftvafer loses more aircraft than expected, not to enemy action, but to mechanical failures and accidents. Ammunition runs short. Spare parts run shorter. The army that looked invincible in propaganda news reels is, in truth, running on fumes and willpower.

But these problems are easy to ignore when you’re winning, and Hitler is winning. He brushes aside reports of shortages and equipment failures. He dismisses generals who raise concerns. He points to the map, Poland conquered, Germany’s eastern flank secured, and asks what more proof anyone could possibly need. The wonder weapons would have been nice to have, but clearly they weren’t necessary.

The following spring, Hitler strikes again. [clears throat] Norway and Denmark fall in April. Then in May, the impossible happens. The German army attacks France, not through the heavily fortified Majino line, but through the Arden Forest, a route French commanders had dismissed as impossible. Within 6 weeks, France surrenders.

The British army barely escapes at Dunkirk, leaving behind nearly all its heavy equipment. Europe is stunned. Hitler, it seems, has proven every doubter wrong. And yet, and yet, look closer at those victories, and cracks begin to appear. The campaign in France stretched German logistics to the breaking point.

Panza divisions outran their supply lines. Trucks broke down on French roads and couldn’t be replaced. The Luftvafa achieved air superiority, but at a cost. Pilot casualties that would take years to replenish. Aircraft losses that factories couldn’t match. When Guring boasted that the Luftvafa could finish off the British at Dunkirk without army support, he failed.

Over 300,000 Allied soldiers escaped across the channel. They would be back. Britain refused to surrender. Hitler expected a negotiated peace, a recognition of German dominance on the continent. Instead, he got Winston Churchill and a nation that would fight alone if necessary. Suddenly, the quick war Hitler had counted on began to look less certain, and the limitations of his military, the very problems his generals had warned about, started to matter.

The Battle of Britain exposed the Luftwaffer’s weaknesses with brutal clarity. German bombers were designed for tactical support, not strategic bombing. They lacked the range to strike deep into Britain and the payload to do serious damage when they got there. German fighters, superb in short engagements, couldn’t escort bombers over long distances.

and Britain’s radar network, a technology the Germans had underestimated, gave the Royal Air Force crucial early warning of incoming attacks. The Luftvafer had lost nearly 2,000 aircraft. Pilot training programs couldn’t keep pace. The invasion of Britain was postponed, then quietly abandoned. Hitler turned east toward the Soviet Union, looking for the quick victory that had eluded him in the West.

But the Soviet Union was not Poland. It was not France. It was a vast continental power with limitless manpower and an industrial base that was only beginning to mobilize. When Operation Barbarosa launched in June 1941, the German army achieved stunning initial successes. Millions of Soviet soldiers were killed or captured in the first months.

But the advance slowed as summer turned to fall and fall turned to the deadliest winter in living memory. Now, the consequences of starting too soon became impossible to ignore. German tanks designed for the temperate climates of Western Europe froze in Russian mud and snow. Engines refused to start in temperatures below minus30.

Lubricants solidified. Fuel lines cracked. Soldiers lacked winter clothing because supply planners had assumed the campaign would be over before the cold set in. The wonder weapons that might have made a difference, the jets that could have swept Soviet aircraft from the skies, the rockets that could have struck factories beyond the reach of conventional bombers, were still years away from deployment.

The war Hitler had planned to win in months became a war of years. And in a long war, everything his generals had warned about came true. Germany’s economy couldn’t match Allied production. American factories, untouched by bombing, churned out tanks and planes and ships at rates that dwarfed German output. Soviet industry, relocated beyond the Eural Mountains, produced more T34 tanks in a single year than Germany could build in three.

Britain’s Royal Navy strangled German supply lines, while the Yubot fleet, still waiting for those revolutionary submarines, suffered catastrophic losses in the Atlantic. By 1943, the tide had turned irreversibly. The German army retreated from Stalinrad in ruins. Allied bombers pounded German cities around the clock.

And the wonderweapons that Hitler had once dismissed as unnecessary, became an obsession, a desperate hope that technology could reverse what strategy had lost. The jets finally arrived. The Mi262, the world’s first operational jet fighter, entered service in 1944. Allied pilots who encountered it described the experience as terrifying. The jet was faster than anything in their arsenal, capable of slashing through bomber formations with near impunity, but there were never enough of them.

Production was sabotaged by Allied bombing. Fuel was scarce. Trained pilots were scarcer. Hitler, in one of his most disastrous decisions, insisted that many ME262s be converted to bombers rather than fighters, squandering their greatest advantage. The rockets came too. The V2 rained down on London and Antwerp, killing thousands of civilians.

But its accuracy was poor, its warhead too small to cause strategic damage, and its production costs astronomical. Each V2 consumed as many resources as several conventional aircraft, and it came too late to matter. The super submarines arrived last of all. The type then, the revolutionary design that could have changed the Battle of the Atlantic, finally entered service in the spring of 1945.

By then, Germany had already lost control of the seas. Most type Fentines never fired a torpedo in combat. They surrendered in port as allied forces closed in from east and west. This was the tragedy that Ludvig Beck had foreseen. This was the disaster that France Halder had tried to prevent. Germany went to war with the weapons she had, not the weapons she was promised.

And when the war lasted longer than Hitler expected, when it became a grinding contest of industrial might and national endurance, the missing wonder weapons became the margin between survival and annihilation. But here’s the haunting question that historians still debate. What if Hitler had waited? Imagine a Germany that delays the invasion of Poland until 1942 or 1943.

By then, the jets might be ready. The submarines might be operational. The rockets might be accurate enough to matter. The Panza divisions might be equipped with Tigers and Panthers from the start, not the light tanks that struggled against French armor in 1940. Would that Germany have won? The answer is almost certainly no.

And the reason goes back to the fundamental miscalculation that Hitler made in 1939. Hitler believed that time was on his side if he acted fast and against him if he waited. But the opposite was true. Every year that passed, Germany’s relative advantage shrank. Britain was rearming at a furious pace. The Soviet Union was rebuilding its officer core and modernizing its military.

The United States, even in its isolationist phase, was beginning to prepare for a war that many Americans saw as inevitable. And the German economy, strained by rearmament dependent on imports vulnerable to blockade, could not sustain an arms race against the combined industrial power of the future allies.

The wonder weapons were never going to save Germany. They were never going to be ready in sufficient numbers. They were never going to overcome the fundamental imbalance in resources and manpower that doomed the Nazi war effort from the start. What the wonder weapons represented was not a path to victory but a symptom of the magical thinking that permeated Hitler’s strategic vision. He believed in shortcuts.

He believed in technological miracles. He believed that German ingenuity and willpower could overcome any material disadvantage. And he was wrong. The generals who stood in that cramped room in August 1939 understood this. They understood that war is not won by prototypes and promises.

It is won by production lines and logistics, by training programs and supply chains, by the grinding, unglamorous work of turning raw materials into weapons and weapons into victories. They tried to tell Hitler that Germany wasn’t ready. They tried to buy time for the factories and the engineers and the training schools. But Hitler wasn’t interested in buying time.

He was interested in making history and on September 1st, 1939, he made it. The decision to invade Poland was not a military decision. It was a political decision, a personal decision, a gamble made by a man who had convinced himself that his instincts were more reliable than his experts analysis. Hitler looked at the map and saw opportunity.

He looked at his generals and saw fear. He looked in the mirror and saw a man running out of time. And so he rolled the dice. For a while the dice came up in his favor. Poland fell, France fell, most of Europe fell. The wonder weapons seemed unnecessary. The general’s warnings seemed overblown. And Hitler’s legend as an infallible strategist seemed secure.

But wars are not won in weeks or months. They are won in years. And when the years stretched on, when the quick victories gave way to grinding attrition, when the Allies mobilized their full industrial mightand the Soviet Union threw wave after wave of men and machines against the German lines, the true cost of starting too soon became clear.

Germany lost the Second World War for many reasons. poor strategy, racist ideology that turned potential allies into enemies, disastrous decisions at Stalinrad and Normandy and 100 other battlefields. But underlying all of these was a single foundational error. Hitler went to war before he was ready against enemies who would only grow stronger with time, betting everything on a quick victory that never came.

The wonder weapons were not a secret advantage, waiting to be deployed. They were an admission of desperation. They were proof that Germany was fighting with one hand tied behind her back, waiting for reinforcements that arrived too late and in too small numbers to matter. When the Mi262 finally screamed through the skies over Germany in 1944, it was a marvel of engineering, but it was also a monument to failure.

A weapon that should have dominated the skies in 1941, arriving three years too late to save the Reich. When the V2 struck London, it was a glimpse of the future, a harbinger of the ballistic missiles that would later hold the world hostage. But in 1944, it was a terror weapon without strategic value, a waste of resources that could have built thousands of conventional weapons.

When the Type Fanin submarines finally slipped beneath the waves in 1945, they were the most advanced undersea vessels ever built. But the war was already lost and most of them never saw combat. This is the lesson of the wonder weapons. Not that they didn’t work. Many of them worked brilliantly. Not that they weren’t revolutionary. They changed warfare forever.

But that they weren’t ready. They weren’t ready because Hitler refused to wait. and Hitler refused to wait because he believed his own legend more than he believed his own generals. In that cramped room in August 1939, France Halder tapped a line in a technical report and tried to explain what earliest operational readiness actually meant.

He tried to explain that schedules are not just numbers on a page. They are the accumulated constraints of physics and engineering, of factory capacity and raw material supply, of test flights and failed prototypes and redesigns. He tried to explain that you cannot will a jet engine into existence. You cannot demand that a rocket guidance system work before the underlying science is understood.

Hitler listened and then he ignored everything Halda said because Hitler had learned the wrong lesson from his own success. He had bluffed his way to power. He had bluffed his way through the remilitarization of the Rhineland when a single French division could have stopped him. [clears throat] He had bluffed his way through the annexation of Austria and Czechoslovakia when his own generals expected the allies to call his hand. And he had won every time.

He thought war would be the same. another bluff, another gamble, another roll of the dice that would come up in his favor because he was Adolf Hitler and history was on his side. He was wrong. The war that began on September 1st, 1939 did not end quickly. It lasted 6 years. It killed tens of millions of people.

It destroyed cities and nations and entire ways of life. And when it was over, Germany lay in ruins, divided between the powers that had combined to defeat her. The wonder weapons survived in a sense. The scientists who built them were scooped up by the victors, transplanted to America and the Soviet Union, put to work on the next generation of jets and rockets and submarines.

Verer von Brown, the young engineer who had spent the war perfecting the V2, would later send American astronauts to the moon. The technology that failed to save Nazi Germany would reshape the entire world. But for the men who gathered in that room in August 1939, for Kitle and Yodel and Halder and all the others who tried and failed to make Hitler understand, there was only the bitter knowledge that they had been right.

They had warned him. They had shown him the numbers. They had explained in terms that should have been impossible to misunderstand that Germany was not ready for the war he wanted to fight. and he had ignored them because he was Adolf Hitler and Adolf Hitler did not wait. History does not record what Halddera said when Hitler asked how long.

The memorandum in the sealed folder has been lost to time, its specific contents reconstructed only from fragmentaryary references in other documents. We know what it contained in general terms, production schedules, test results, estimates of when key weapons might become operational. We know that the news was not what Hitler wanted to hear, but we can imagine the silence that followed the question.

We can imagine the generals exchanging glances, each hoping someone else would speak first. We can imagine Halder clearing his throat, choosing his words carefully, trying to find a way todeliver the truth without sounding like a defeist or a coward. And we can imagine Hitler’s response, the dismissive wave of the hand, the insistence that these technical details did not matter, the conviction that German soldiers and German willpower would overcome any material shortfall.

The decision already made before he even entered the room, to proceed with the invasion, regardless of what any report might say. The folder was opened, the contents were read, and the world changed forever. 6 years later when Soviet soldiers raised the red flag over the Reichag when American and British troops liberated concentration camps and discovered horrors beyond imagination.

When the full cost of Hitler’s gamble became impossible to deny, the wonder weapons lay scattered across Europe like broken promises. Captured jets rusted on airfields. V2 components gathered dust in underground factories. Submarines surrendered in their pens, never having fired a shot. They had been too late.

They had always been too late. And the man who had refused to wait for them was dead by his own hand in a bunker beneath the burning streets of Berlin. This is why history matters. Not because it tells us what happened, but because it shows us how decisions are made. It shows us the gap between what leaders believe and what is actually true.

It shows us the danger of magical thinking, of betting everything on technology that doesn’t exist yet, of trusting intuition over evidence. Hitler’s generals begged him to wait for the wonder weapons. He refused, and the world paid the price. The ruins of that decision still mark the landscape of Europe.

The lessons of that decision still echo in the halls of power, where leaders make choices about war and peace. The ghosts of that decision still haunt the descendants of the millions who died because one man believed he could outrun time itself. He couldn’t. No one can. The weapons came too late. The war lasted too long.

And the man who started it all never lived to see the world he created. But we live in it. We inherit its scars and its lessons. And every time a leader ignores expert advice, every time a nation rushes toward conflict without counting the cost, every time someone bets everything on a shortcut that doesn’t exist, the story repeats itself.

The folder on the table, the memorandum no one wants to read, the line underlined so hard the page has torn. And the question that hangs in the air like a held breath, how long? The answer when it came was not what Hitler wanted to hear, but he gave the order anyway and the world burned. Your support helps us continue the deep research behind every episode.

Buy us a coffee and fuel the next documentary. Link is in the description. Thank you for watching and thank you for remembering.