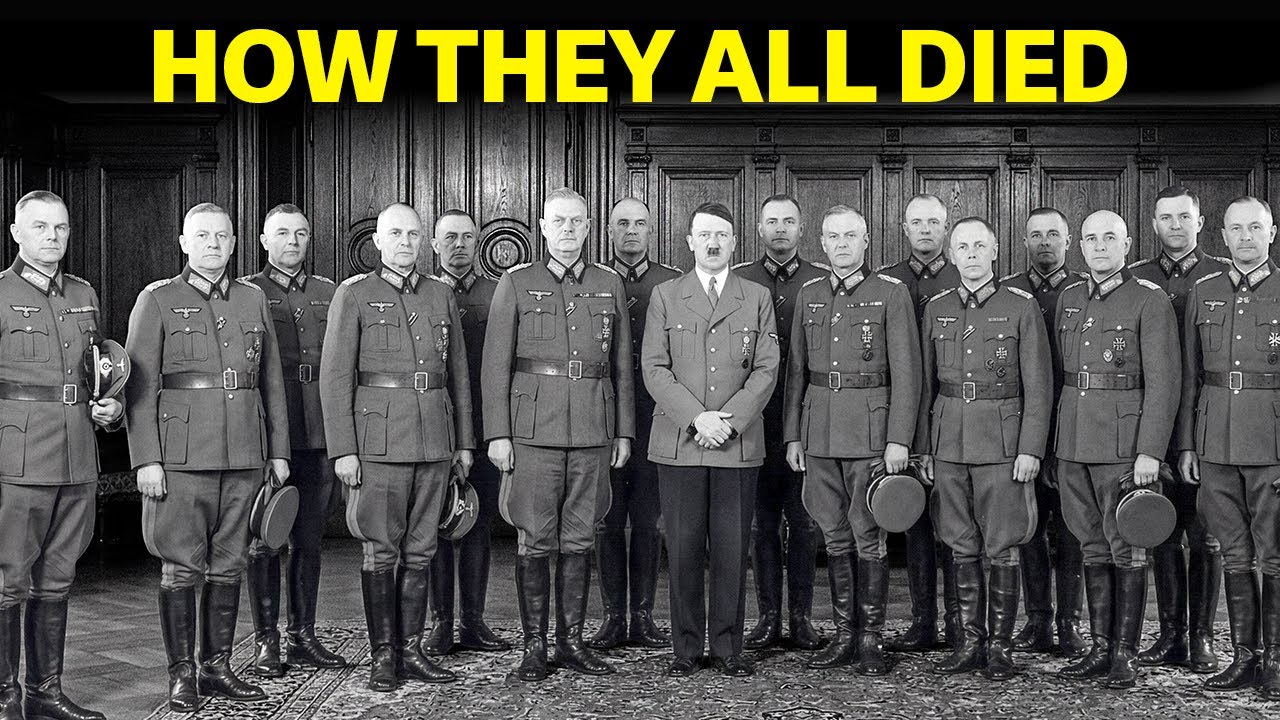

26 men wore the field marshals baton under Adolf Hitler, including Herman Guring, who would later hold an even higher rank. It was the highest military rank the Third Reich could bestow, a promise of glory, a guarantee of legacy, and as it turned out, a death sentence written in invisible ink.

One was hanged at Nuremberg. Some shot themselves in bunkers, forests, and burning cities as the Reich collapsed around them. Some rotted in Soviet camps, forgotten by everyone except their jailers. A few lived long enough to write memoirs and recast themselves as reluctant servants of a regime they claimed to despise. But every single one of them answered for what they did or for what they failed to stop.

This is the final ledger, the sealed files, the complete accounting of how Hitler’s top commanders met their end. And the pattern that emerges from these 26 fates may disturb you more than any single death ever could. To understand how these men died, you first have to understand what they were promised. The rank of General Feld Marshall carried weight that went back centuries.

Frederick the Great had elevated the title. Bismar’s wars had made it sacred. Hindenburg and Ludenorf had embodied its power in the First World War. To become a German field marshal was to enter an aristocracy of command. To be untouchable, unquestionable, immortal in the annals of military history. Hitler understood this mystique better than anyone.

He used the baton as a tool, dangling it before his generals like a diamond on a string. Perform brilliantly, and you would join the pantheon of German military greatness. Fail, and you would be discarded like a broken instrument. What? None of these men fully understood, not at the beginning, was that Hitler was building something fundamentally new.

Not a professional military elite bound by tradition and honor, but a personal instrument of ideological conquest. And instruments once broken are thrown away without sentiment. The first man to learn this brutal lesson was Veron Bloomberg. In 1936, Bloomberg became the first officer Hitler promoted to field marshal in the Nazi era.

He was the minister of war, the man who had overseen Germany’s secret rearmament and prepared it for the wars of expansion to come. Bloomberg believed in Hitler with the fervor of a convert. He believed the furer was Germany’s salvation after the humiliations of Versailles. That faith made him blind to the dangers coiling around him.

In January 1938, Bloomberg married a woman named Margaret Grun. He was 60 years old and in love for the first time in years. Hitler himself served as a witness at the wedding. It seemed like a fairy tale until police files surfaced within days, showing that his new bride had a past. There were photographs, a criminal record, associations that no officer’s wife could survive in the rigid social world of the German military.

The scandal was almost certainly engineered. Hinrich Himmler and Herman Guring wanted Bloomberg gone and Hitler faced with the embarrassment let it happen. Bloomberg was forced to resign in disgrace. Exiled from the army he had helped rebuild. He spent the war years in Bavaria, forgotten and humiliated, while the conflicts he had helped prepare unfolded without him.

When the allies arrived in 1945, they arrested him as a potential war criminal, but there would be no trial. Verer von Bloomberg died in American custody in Nuremberg on March 14th, 1946. A broken man, the first Field Marshall of the Nazi era, never commanded troops in battle under Hitler. He was destroyed by politics before the shooting even started.

And that set the dark tone for everything that followed. With Bloomberg gone, Hitler needed a new commander-in-chief for the army. He chose Wa von Brow, a career officer with an aristocratic bearing and a reputation for agreeing with whoever held power. Brow looked the part of a Prussian general, tall, dignified, impeccably uniformed.

But beneath the polished exterior was a man who lacked the iron will to stand up to Hitler when it mattered. Brahitch was promoted to field marshal after the stunning victory over France in July 1940 when German arms seemed invincible and the future appeared to belong to the vermach. But Brahic was no true believer in national socialism.

He was simply a man who followed orders because that was what German officers had always done. When Operation Barbarosa began to stall in the frozen mud outside Moscow in the winter of 1941, Hitler needed someone to blame for the failure. Brahitch became that man. On December 19th, 1941, Hitler dismissed him in a fury and took personal command of the German army himself.

A fateful decision that would shape the remainder of the war. Brahitch retreated into private life, suffering from chronic heart disease and the crushing knowledge that his years of obedience had enabled catastrophe on an unimaginable scale. He was arrested by the British after the war and slated for trial as a war criminal, but justice never came.

Wa von Brahich died in British custody in Hamburg on October 18th, 1948, awaiting a trial that would never take place. He had commanded the German army during the invasions of Poland, France, and the Soviet Union. Millions had died under orders that bore his signature, and in the end, he simply faded away. A bureaucrat in uniform whose heart gave out before any court could render judgment.

But not all of Hitler’s field marshals would escape so quietly. Some would face the hangman’s noose, and the most infamous of them all was Wilhelm Kitle. But before following that dark thread, there is one name that must be entered into the ledger. A man who received the baton as an honor rather than a command. Edward Fryhair Fonbum Emoly was an Austrohungarian relic, a field marshal from the old Habsburg Empire who had commanded armies in the First World War.

October 31st, 1940, Hitler granted him an honorary promotion to German General Feld Marshal, a gesture of respect to the aging warrior and a symbolic unification of German and Austrian military traditions. Boomi was 84 years old and long retired. He never commanded a single German soldier in the Second World War.

He died peacefully in his bed in Vienna on December 9th, 1941. While the Vermacht was still advancing on all fronts, his was perhaps the gentlest fate of any man to hold the rank. A ceremonial honor followed by a quiet end, untouched by the catastrophes that would consume his fellow field marshals.

Now back to the men who would face the hangman. Kitle was not a warrior in any meaningful sense. He was an administrator, a manager, a man who specialized in translating Hitler’s volcanic rages into precise military directives. As chief of the high command of the armed forces, the OKW, Kitle sat at Hitler’s right hand for the entire war.

He was therefore every major decision, every strategic conference, every order that sent German armies rolling across Europe. and he signed documents that made him complicit in mass murder on a continental scale. The Commasar Order which mandated the execution of captured Soviet political officers. The night and fog decree which caused thousands of resistance fighters to vanish into concentration camps.

Directives that transformed the Vermachar from a professional fighting force into an instrument of genocidal warfare. Other generals despised him. They called him Leitel, a contemptuous pun on the German word for lackey. He never objected to this characterization. He never resigned in protest. He never pushed back against even the most criminal orders.

He simply nodded, clicked his heels, and signed. When Berlin fell in May 1945, it was Wilhelm Kitle who signed the instrument of unconditional surrender on behalf of the German armed forces. And when the International Military Tribunal convened at Nuremberg, Kitle sat in the dock, his face gray with exhaustion, his excuses hollow and unconvincing.

He claimed he was merely a soldier following orders. The tribunal did not agree. On October 16th, 1946, Wilhelm Kitle was led to the gallows in the gymnasium of Nuremberg prison and hanged. He was the highest ranking German military officer executed for war crimes. The field marshall’s baton that Hitler had bestowed upon him offered no protection whatsoever.

Kitle’s fate before the hangman was shared by one other field marshal. But this one had turned against Hitler before the end and died for his defiance rather than his obedience. Vin Fonvitz Lebanon was an old school Prussian officer who came to despise the Nazis almost from the moment they took power.

He had been a career soldier since before the First World War, steeped in the traditions of the German officer Corps. Hitler promoted him to field marshal after the French campaign in 1940, recognizing his skill as a commander. But by 1942, Vitz Laben was in active contact with the German resistance. His health had forced him into retirement, but his hatred for the regime had only intensified when the conspiracy to assassinate Hitler crystallized around Colonel Klaus von Stalenberg in 1944.

Vitz Laben was designated to play a crucial role. If the bomb killed Hitler, Vitz Leen would become commanderin-chief of the Vermacht and oversee the military takeover of the government. On July 20th, 1944, Stalenberg’s briefcase bomb exploded in Hitler’s headquarters in East Prussia. Hitler survived. Within hours, the conspiracy collapsed and the Gestapo began making arrests.

Vitz Leen was seized almost immediately. The trial that followed was a spectacle of calculated humiliation. The Nazis stripped Vitz Laben of his uniform and forced him to appear in court wearing ill-fitting civilian clothes. They denied him a belt so he had to hold up his trousers while the notorious Nazi judge Roland Fryler screamed abuse at him.

Vitz Leen remained defiant to the end. On August 8th, 1944, he was taken to Plutensi prison in Berlin and hanged with piano wire from a meat hook. Hitler ordered the execution filmed for his personal viewing. Vitz Leen died slowly and in agony, a warning to anyone else who might consider defiance. He remains the only German field marshal executed by his own government for treason.

His courage cost him everything, but he died on his feet, not his knees. The July 20th conspiracy claimed more victims than Vitz Leen. Its tentacles reached deep into the highest levels of the German officer Corps and it touched the most famous German military commander of the entire war. Irwin RML needed no introduction even in 1944.

The desert fox had become a living legend in North Africa. a commander whose tactical brilliance and personal charisma had humiliated the British army and earned the grudging respect of his enemies. Churchill himself had praised RML in the House of Commons, a remarkable tribute to pay to a foe. Hitler had promoted RML to field marshal in June 1942, making him the youngest German officer to hold that exalted rank.

RML seemed to embody everything the Nazi propaganda machine wanted in a military hero. Dashing, aggressive, victorious, and apparently loyal to the Furer. But by 1944, RML was a changed man. He had seen the war from the inside. He had witnessed the hopelessness of the strategic situation, the inevitability of Allied victory, and the catastrophic consequences of Hitler’s leadership.

and he had come to believe that the furer had to be removed if Germany was to be saved from total destruction. RML’s exact involvement in the July 20th plot remains a matter of historical debate. He may not have known specifically about the bomb. He may have preferred to arrest Hitler rather than assassinate him, but he knew about the conspiracy and he did nothing to report it or stop it.

That passive complicity was enough. When the plot failed and the Gestapo began unraveling the network of conspirators, RML’s name surfaced in confessions extracted under torture. Hitler faced an impossible dilemma. He could not put the desert fox on trial. RML was too popular, too beloved by the German people, too useful as a propaganda symbol.

A public execution would be a disaster that might shake faith in the regime itself. So Hitler offered RML a devil’s bargain. Take poison and your death will be announced as the result of your war wounds. You will receive a state funeral with full military honors. Your family will be protected and receive a pension. Refuse and you will be arrested, tried before the people’s court, inevitably convicted, and executed as a traitor.

Your family will be arrested under Sippenhaft. Collective punishment for your crime. On October 14th, 1944, two generals arrived at RML’s home in Herlingan with the ultimatum. RML said goodbye to his wife Lucy and his son Manfred, walked to the waiting car, and swallowed the cyanide capsule they had brought. He was dead within 15 minutes.

The Nazi regime gave him a hero’s funeral. Hitler sent a wreath. The truth about Raml’s death did not emerge until after the war ended. His death is often called a suicide, but it was murder by ultimatum. A field marshall destroyed by the very regime he had served with such distinction.

RML was not alone in choosing death over capture or trial. As the war turned irrevocably against Germany in 1944 and 1945, suicide became almost epidemic among the high command and few deaths illustrated the collapse more starkly than that of Gaon Kluga. Kluga was a capable and experienced commander who had led German armies with distinction in France and on the vast Eastern front.

Hitler had promoted him to field marshal in July 1940, recognizing his skill during the campaign against France. For years, Kug served with apparent loyalty even as his private doubts about Hitler’s leadership grew increasingly acute. He had been approached by the resistance, but had never committed himself fully to their cause.

A fence sitter who could never quite decide which side of history he wanted to be on. By the summer of 1944, Kug was commanding all German forces in the West, desperately trying to contain the Allied breakout from Normandy following D-Day. He failed. The front collapsed under the weight of Allied material superiority and air power. And then Hitler began receiving reports, possibly accurate, possibly fabricated, that Kug had attempted to contact the Allied commanders about negotiating a separate piece.

Whether these reports were true hardly mattered, the accusation alone was fatal in the paranoid atmosphere following the July 20th attempt on Hitler’s life. On August 17th, 1944, Hitler dismissed Kug from command and ordered him to return to Berlin immediately. Kug knew exactly what that summons meant. He had seen what happened to officers who fell from Hitler’s favor.

Somewhere on the road between the front lines and the German capital, Ga Fonluga pulled out a cyanide capsule he had been carrying and swallowed it. His body was found in his staff car near Mets. He left behind a letter to Hitler, a strange document mixing continued expressions of loyalty with despair over Germany’s hopeless situation. The baton had not saved him.

Nothing could have. Clue’s lonely death on that French road was not unique. Less than a year later, another field marshal would follow his example under even more dramatic circumstances. Walter Mod was Hitler’s ultimate troubleshooter. the general who was sent to stabilize fronts that were collapsing into chaos.

He earned the nickname the furer’s fireman because he was repeatedly dispatched to crisis where other commanders had failed. Model had held army group center together after operation begratian destroyed it in the summer of 1944 preventing a complete route. He had commanded army group B during the Arden offensive, the battle of the bulge.

fighting to extract something from Hitler’s last desperate gamble in the West. Model was fierce, fanatical in his devotion to duty and utterly committed to resistance until the end. He was not a Nazi ideologue, but he believed in Germany and in the soldiers obligation to fight. By April 1945, however, even Model’s legendary determination had reached its limits.

His army group B was encircled in the Rur industrial region by American forces. Trapped in what became known as the Rur pocket. 300,000 German soldiers were about to become prisoners of war. Model refused to surrender. He disbanded Army Group B, releasing his soldiers from their oath of allegiance so they could surrender individually without dishonor.

Then on April 21st, 1945, Walter Model walked alone into a small forest near Doober. He drew his pistol and shot himself in the head. His body was discovered days later, still wearing his field marshall’s uniform. Model had once told his staff that a German field marshal does not become a prisoner of war.

He kept that vow in the only way remaining to him. But the suicides were not confined to the forests of the collapsing Reich. They continued in the burning ruins of Berlin itself, even as Soviet shells fell on the heart of the government. Robert Ritter Fon Grime holds the distinction of being the last man Hitler ever promoted to field marshal, and his story is one of the strangest episodes of the war’s final apocalyptic days.

Grime was a Luftvafa general, a decorated ace from the First World War who had remained fanatically loyal to Hitler when others began to waver. In late April 1945, as Soviet forces closed in on the Reich Chancellery and artillery shells shook the bunker where Hitler had taken refuge, the Fura summoned Graeme to Berlin.

Flying into a city under siege was effectively a suicide mission. The skies above Berlin were filled with Soviet fighters. Streets were battlegrounds, but Grime came anyway. Piloted by the equally fanatical aviator Hannah Reich in a small fascela storch aircraft, their plane was hit by Soviet anti-aircraft fire during the approach.

Grime was seriously wounded in the leg. They crash landed near the Brandenburgg gate and made their way through the rubble and gunfire to Hitler’s bunker. There, in the flickering candle light of Germany’s last redout, Hitler promoted Grime to field marshal and named him commanderin-chief of the Luftvafer, replacing Herman Guring, who had just been stripped of all offices for alleged treason.

It was a completely meaningless appointment. The Luftvafer barely existed as a fighting force anymore. Fuel was exhausted. Aircraft were destroyed. Pilots were dead or captured. But Grime accepted his impossible command. He and Reich flew out of Berlin in another harrowing escape and Grimes surrendered to the Americans a few days later.

He was taken to a hospital in Salsburg to treat his wounds. On May 24th, 1945, less than a month after his promotion, Robert Ritter von Grime swallowed a cyanide capsule and died. He was the last officer to receive Hitler’s baton. He carried it for less than a month. But Grime was not the most famous Luftvafa commander to die by his own hand.

That grim distinction belongs to Herman Guring himself. The only man in the Third Reich to hold a rank above Field Marshall. Reich’s Marshal of the Greater German Reich. Guring had been at Hitler’s side since the earliest days of the Nazi movement. He had been designated as Hitler’s successor, the number two man in the Reich.

As head of the Luftvafer, he had promised to destroy the Royal Air Force and bomb Britain into submission. As head of the four-year plan, he had directed the German economy for war. As Reich Marshall, he had accumulated power, wealth, and influence that made him second only to Hitler himself. But Guring was also grotesqually corrupt, openly stealing art from conquered nations.

He was addicted to morphine, increasingly detached from military reality, and growing ever more bloated and ineffective as the war dragged on. By 1945, Guring sensed that Hitler was finished. When he sent a telegram from his refuge in Bavaria suggesting that he should assume leadership of the Reich if Hitler remained trapped in Berlin, the furer exploded in rage.

Hitler ordered Guring stripped of all offices, expelled from the Nazi party, and placed under arrest for high treason. [clears throat] It was the end of a partnership that had lasted more than two decades. Guring surrendered to American forces in May 1945, expecting to be treated as a head of state, perhaps even as a negotiating partner for postwar arrangements.

Instead, he found himself in the dock at Nuremberg on trial for crimes against humanity alongside the other surviving Nazi leaders. The evidence against him was overwhelming. Guring was found guilty on all counts and sentenced to death by hanging. But on the night of October 15th, 1946, just hours before his scheduled execution, Herman Guring bit down on a cyanide capsule that had been hidden in his cell throughout his imprisonment.

He died with something like a smirk on his face, cheating the hangman by mere minutes. To this day, no one knows with certainty how he obtained the poison or kept it hidden from his guards. The Reichs Marshall’s final act was one last escape, one last gesture of contempt for the justice that had finally caught up with him.

The suicides and the executions tell one kind of story. But many of Hitler’s field marshals survived the war only to face a slower and more ambiguous reckoning. And some of those stories are stranger than any death on a battlefield. Friedrich Powus was the commander who led the German 6th Army to Stalinrad in the summer of 1942.

His forces had driven deep into the Soviet Union, reaching the banks of the Vular River, fighting through the ruins of the city that bore Stalin’s name. Then the trap closed. In November 1942, Soviet forces launched Operation Uranus, encircling Powus and nearly 300,000 German soldiers in a pocket of frozen rubble.

Hitler refused to authorize a breakout. He ordered Powless to hold at all costs, promising supplies by air that never arrived in sufficient quantities. For months, the Sixth Army starved and froze while Soviet forces tightened the noose. In January 1943, as the situation became utterly hopeless, Hitler promoted Pace to Field Marshall. It was a deliberate signal, not an honor.

No German field marshal had ever surrendered to an enemy. Hitler expected Powus to take his own life rather than accept capture. Powus did not oblige. On January 31st, 1943, he surrendered to Soviet forces, becoming the first German field marshal in history to be taken prisoner. Hitler was apoplelectic with rage, calling Powus a coward and a traitor.

Paul spent the remainder of the war in Soviet captivity where over time he underwent a remarkable transformation. He eventually signed propaganda statements denouncing the Nazi regime and calling for German soldiers to surrender. He testified for the Soviet prosecution at Nuremberg. After the war, Powus was released and chose to live in East Germany behind the Iron Curtain, a ghost haunted by the catastrophe he had presided over at Stalingrad.

He died in Dresdon on February 1st, 1957, largely forgotten by history, a cautionary tale about the consequences of obedience taken beyond all reason. Pace was not the only field marshal to perish in Soviet hands, though his end was comparatively gentle compared to what awaited others. Uold von was a brilliant Panza commander, one of the architects of German armored warfare.

He had led the armored spearhead that pierced through the Arden in 1940, shattering the French front. He had commanded the dash to the Caucus’ oil fields in 1942, driving German forces deeper into Soviet territory than any other general. Hitler promoted him to field marshall in February 1943. But Kle ran a foul of the Furer by criticizing Nazi treatment of civilian populations in occupied territories, an unusual moral stance for a German senior commander.

He was dismissed in March 1944 and spent the rest of the war in retirement. When the war ended, Klest surrendered to American forces, hoping for fair treatment. That hope was misplaced. The Americans transferred him to Yugoslav custody to face war crimes charges and Yugoslavia in turn handed him over to the Soviet Union. He was tried by a Soviet military tribunal and sentenced to prison.

Yuvold von Kle died in Vladimir prison deep inside the Soviet Union in November 1954. He was 73 years old and had not seen freedom in nearly a decade. His crime in the end was simply being a German field marshal at a time when the Soviets wanted trophies more than they wanted justice. But most of the surviving field marshals found their way western occupation zones where the reckoning took different and often more lenient forms.

Ger von runstead was the elder statesman of the German officer corps. A relic of an older era whose career stretched all the way back to the Kaiser’s army before the first world war. He had commanded Army Group South during the invasion of Poland, Army Group A during the conquest of France, and Army Group South during the initial advance into the Soviet Union.

Hitler had dismissed and recalled him multiple times throughout the war. Their relationship a constant cycle of exile and reluctant reinstatement. By 1945, Runstead was exhausted, ill, and thoroughly disillusioned with everything the war had become. He surrendered to the Americans and was held as a prisoner of war.

The British seriously considered putting him on trial for war crimes, but Runstead’s failing health made prosecution impractical. He was released in 1949 and spent his final years in Hanover, occasionally granting interviews and maintaining to the end that he had merely been a professional soldier performing his duty. He died on February 24th, 1953 at the age of 77, never having faced a tribunal.

His reputation remains contested to this day. Was he a decent man trapped in an impossible situation or simply another enabler of atrocity who escaped accountability through luck and longevity? History has never rendered a final verdict. Fedor vonbach was the commander who came closest to Moscow in the terrible winter of 1941 before the Russian counteroffensive hurled his forces back from the Soviet capital.

Hitler dismissed him in July 1942 after a dispute over strategy and Bach never held another major command. He spent the remaining years of the war in embittered retirement watching from the sidelines as the Reich he had served collapsed around him. On May 3rd, 1945, just 5 days before Germany’s unconditional surrender, Boach was traveling by car near the town of Lenzan.

A British fighter aircraft spotted the vehicle and strafed it. His wife, stepdaughter, and friend were killed instantly. Boach himself was badly wounded. He died the following day, May 4th, 1945, from his injuries. Fedor vonbach had survived every battle of the eastern front, every crisis of command, every political intrigue, only to die from a random attack on a country road in the war’s final hours.

The violence found him anyway when he thought himself safe. Wilhelm Rita von Leeb commanded army group north during the invasion of the Soviet Union and the early stages of the 900day siege of Lenengrad. He clashed repeatedly with Hitler over strategy and the proper conduct of operations and was dismissed from command in January 1942.

After the war, Leeb was tried at Nuremberg in the high command trial of senior German military officers. He was convicted of transmitting criminal orders to his subordinates but sentenced only to time already served. He was released immediately and spent the rest of his life in Bavaria, dying on April 29th, 1956.

Leeb had been one of the few German field marshals to express written criticism of Nazi atrocities while the war was ongoing. Yet his protests never extended to resignation or active resistance. That fundamental ambiguity defined his legacy. The pattern of compromised justice repeated itself throughout the postwar period as field marshall after field marshall avoided the full consequences of their service.

Ernst Bush had commanded army group center when it was catastrophically destroyed by the Soviet summer offensive known as operation bagraton in June and July 1944. Hitler blamed Bush for the disaster, the worst defeat in German military history, and dismissed him in disgrace. Bush was captured by the British at the end of the war and held as a prisoner.

He died in British captivity on July 17th, 1945, just weeks after Germany’s surrender. Official cause was heart failure. He was 60 years old. Whether the stress of defeat contributed to his death, no one can definitively say. Wilhelm List commanded Army Group A during the drive toward the Caucusesus in 1942 before being dismissed by Hitler for moving too cautiously.

He was tried at Nuremberg in the hostages trial for brutal reprisals against civilians in the Balkans during his earlier service there and was sentenced to life in prison. But he was released in 1952 due to deteriorating health and spent the rest of his lengthy life in quiet obscurity. He died in 1971 at the age of 91.

One of the longest lived of all the German field marshals. A man who had largely escaped the weight of historical judgment through the simple biological luck of outlasting his prosecutors. Gayorg von Kukla succeeded Leeb in command of army group north and thus bore responsibility for the continuation of the Leningrad blockade.

900 days of siege killed million Soviet civilians through starvation, disease and bombardment, one of the deadliest events in human history. After the war, Kucula was tried for war crimes, convicted and sentenced to 20 years in prison. He was released in 1953 and died in 1968. His role in Lenningrad’s agony earned him conviction, but the sentence was far lighter than the crime might seem to warrant.

The scales of justice proved inconsistent in their application. Maxmillian vonvikes commanded in the Balkans and on the Eastern Front, overseeing operations during some of the most brutal campaigns of the war. He was indicted for war crimes after the war ended, but he was never actually tried. The proceedings were discontinued because of ill health, and Vikes died in 1954, yet another field marshal who slipped through the cracks of postwar accountability.

Walt von Richau was different from most of his fellow field marshals. He was a true believer in national socialism. One of the few senior commanders who embraced Nazi ideology with genuine enthusiasm rather than mere accommodation. He commanded the Sixth Army during the invasion of the Soviet Union and issued orders explicitly calling for the annihilation of Soviet commisars and Jews behind the front lines.

His brutal directives helped set the tone for the war of extermination in the east. But Raichana never faced justice. In January 1942, while still in command, he suffered a massive stroke. He was being evacuated by air to Germany for treatment when his plane crashed on landing. Risha died on January 17th, 1942. Whether from the stroke itself or from injuries sustained in the crash has never been determined with certainty.

He was one of the few German field marshals to die during the war itself. History never had a chance to render its verdict on him in any court of law. The Luftvafer produced its own field marshals and their fates varied as widely as those of their army counterparts. Albert Kessle ring known as smiling Albert for his perpetual optimism and good humor was one of the most capable German commanders of the war.

He conducted the defense of Italy with such skill that the Allied advance became a grinding attritional struggle lasting nearly 2 years. But Kessler was also complicit in atrocities. He was convicted by a British military tribunal for the Ardotine massacre in Rome where 335 Italian civilians were murdered in reprisal for a partisan attack and for other war crimes.

He was sentenced to death, but the sentence was commuted to life imprisonment. He was released in 1952 due to ill health and spent his final years writing memoirs that defended his wartime record. He died on July 16th, 1960. Like so many of his comrades, Kessle Ring was never fully called to account. Hugo Spearl commanded Luftvafa forces during the bombing of Warsaw, Rotterdam, and the London Blitz.

He was one of the architects of German air terror. Yet, he was acquitted at Nuremberg for lack of direct evidence tying him to specific war crimes. He died in relative obscurity in Munich on April 2nd, 1953. Hehard Mil was deeply involved in both Luftvafa operations and the use of slave labor in German aircraft production.

He was convicted at Nuremberg and sentenced to life imprisonment only to be released in 1954. He spent the rest of his long life as an aviation consultant rehabilitating his reputation with remarkable success. He died in 1972. Wulfr von Rishtoen was the cousin of the legendary Red Baron and one of the most effective Luftvafa tacticians of the war.

He pioneered the close air support techniques used so devastatingly at Gernika Warsaw and across the battlefields of the Eastern Front. But by 1944, Richtoven’s health was failing. He was diagnosed with a brain tumor and retired from active duty. He died on July 12th, 1945, just weeks after Germany’s surrender, killed slowly by the disease that had been growing inside him.

While he waged war across half of Europe, the last surviving German field marshals of the Second World War lived long enough to see their country rebuilt from the ashes. Some attempted to rehabilitate their reputations through memoirs and interviews. None succeeded entirely. Eric Fonmanstein is still regarded by many military historians as the greatest German strategist of the war.

His operational plan for the invasion of France, the famous sickle cut through the Arden was a masterpiece of strategic imagination. His defensive operations on the Eastern Front in 1943 and 1944 demonstrated tactical brilliance under impossible conditions. But Mannstein also commanded in areas where the SS and Enzats group conducted mass murder of Jews and other civilians.

He knew what was happening. He did not stop it. After the war, Mannstein was tried by a British military tribunal and convicted of neglecting to protect civilian lives under his command. He served less than four years of his sentence before being released. He then spent decades advising the West German Bundesphere and writing influential memoirs that presented himself as a pure soldier, a military professional untouched by Nazi ideology.

He died on June 9th, 1973 at the age of 85. His reputation remains a contested battlefield, a military genius who served a criminal regime and never fully reckoned with his own complicity. Ferdinand Sherner was Hitler’s last field marshal. Promoted in April 1945 as the thousand-year Reich crumbled to dust.

Sherner was fanatical, brutal, and feared by his own men as much as by the enemy. He executed soldiers for cowardice, desertion, or simply being in the wrong place at the wrong time. When the end came, Sherner attempted to escape to the West to avoid Soviet captivity, but was captured by the Americans and eventually handed over to the Soviets.

He spent years in prison camps before being returned to West Germany in 1955. There, German authorities tried and convicted him for the illegal execution of German soldiers during the war’s final days. He served 4 years and was released. He died in 1973, unrepentant to the last, still insisting he had only done what was necessary.

And so the ledger finally closes. 26 men received the field marshall’s baton from Adolf Hitler over the course of the Third Reich. Some died by their own hand, swallowing cyanide capsules in bunkers, forests, prison hospitals, and staff cars. Some were executed by the regime they had served or by the victors who sat in judgment at Nuremberg.

Some were killed in action or by random violence in the war’s chaotic final days. Some rotted for years in Soviet camps, forgotten by everyone except their jailers. And some lived for decades afterward, writing memoirs, advising new armies, testifying at trials, and insisting until their dying breaths that they had only been soldiers, that they had merely followed orders, that the crimes were always someone else’s responsibility.

The pattern that emerges from these 26 fates is unmistakable. Rank did not protect them. Tactical brilliance did not protect them. Personal loyalty to Hitler certainly did not protect them. Some of his most devoted followers died in disgrace, while some of his critics survived to old age.

What emerges from this final accounting is a portrait of complicity and its inevitable cost. These men built the machine of Nazi conquest. They oiled its gears with their professional expertise. They watched it grind through millions of human lives across an entire continent. And when that machine finally broke apart in fire and ruin, the shrapnel found every single one of them in the end. 26 men, 26 answers.

The ledger is now closed. If this story gripped you, subscribe and watch the video appearing on screen now because this is just one chapter in the larger story of how the war’s architects met their reckoning.