October 15th, 1943, 25,000 ft above Nazi occupied Europe, American bomber crews watched their escorts peel away at the German border again. The P47 Thunderbolts simply couldn’t carry enough fuel to reach Berlin and back. What happened next was always the same. Messers Schmidt 109’s and Foca Wolf 190s swarmed the defenseless flying fortresses like wolves.

In the cramped North American aviation workshop in Englewood, California, chief designer Edgar Schmood stared at wind tunnel data that his own colleagues called stupid. A wing design that shifted maximum thickness toward the back, defying every rule of conventional aircraft engineering. The established experts said it would never work. Too risky. too experimental.

But Schmood’s calculations showed something impossible. This stupid aerodynamics trick could push a fighter to 440 mph while carrying enough fuel to escort bombers all the way to Hitler’s doorstep. 8 months later, deep in the heart of the Third Reich, German pilots would radio back reports that Allied command refused to believe.

American fighters flying where no Allied fighter had ever flown before. The Laminar flow wing seemed like madness to anyone who understood conventional aircraft design. In the spring of 1944, as Allied bombers continued their devastating losses over Europe, Edgar Schmood found himself defending an idea that violated every established principle of aerodynamics.

The North American Aviation Design Team had gathered in the cramped conference room overlooking the Englewood factory floor where half-completed P51 airframes sat waiting for wings that might never work as intended. Ed Hory spread the wind tunnel photographs across the mahogany table, each image revealing airflow patterns that defied logic.

Traditional fighter wings placed their thickest point at 25% of the cord length, a design principle that had guided aircraft construction since the Wright brothers. But the NACA 66 series wing pushed maximum thickness back to 50%, creating what aerodynamicists called a favorable pressure gradient that kept air flow attached longer to the wing surface.

The theory was elegant in its simplicity. Most aircraft wings created turbulent air flow at high speeds, generating drag that limited performance. The laminer flow design maintained smooth air flow much further back along the wing surface, reducing profile drag by nearly 20%. On paper, this translated to 40 additional mph at cruising speed, enough to transform the Mustang from a capable interceptor into a long range escort fighter that could match the speed of German interceptors while carrying external fuel tanks.

But paper calculations meant nothing without realorld validation. The P-51 prototype had been flying since October 1940, powered by the reliable but underpowered Allison V1710 engine. Early test flights revealed an aircraft with exceptional handling characteristics and good speed, but insufficient range for escort duties beyond the English Channel.

The Allison engine, designed for lowaltitude performance, lost power dramatically above 15,000 ft, exactly where bomber formations needed fighter protection most. Schmood’s breakthrough came from an unexpected source. Rolls-Royce had developed the Merlin 61 engine specifically for high alitude operations, incorporating a two-stage supercharger that maintained power output well above 20,000 ft.

When North American received permission to test fit the Merlin into the Mustang airframe, the Laminer Flow Wing finally had an engine worthy of its potential. The first Merlin powered P-51 took flight on October 13, 1942 with test pilot Bob Chilton at the controls. The aircraft climbed effortlessly to 25,000 ft, maintaining full power output where the Allison version would have gasped for air.

But the real revelation came during high-speed runs. The Laminar flow wing, now paired with adequate power, pushed the Mustang past 420 mph in level flight, faster than any production fighter in the world. Yet speed alone wouldn’t solve the bomber escort problem. Range remained the critical factor. German fighters typically engaged Allied formations between 300 and 500 miles from their English bases, well beyond the combat radius of existing American fighters.

The P47 Thunderbolt, despite its ruggedness and firepower, could barely reach the German border with internal fuel. The P38 Lightning had better range, but suffered from compressibility problems at high altitude that made it vulnerable to German interceptors. The Mustang’s laminer flow wing offered a solution that seemed almost too good to be true.

The reduced drag allowed the aircraft to carry two 75gall drop tanks without significant performance penalty. With internal fuel capacity of 269 gall, the P-51 could theoretically fly over 800 m, engage in combat, and return to base with fuel reserves. Horkey’s calculations showed the wing’s effectiveness extended beyond simple drag reduction.

The NACA air foil maintained its laminer characteristics even with external stores attached unlike conventional wings that became dramatically less efficient when burdened with fuel tanks or bombs. This meant the Mustang could escort bombers deep into Germany while retaining the speed and maneuverability necessary to engage Messersmidt 109’s and Folk Wolf 190s on equal terms.

The first operational test came in December 1943 when the newly formed fourth fighter group received their initial P-51BS at Debdon Airfield in England. Colonel Don Blakesley, a veteran pilot who had flown Spitfires with the Royal Air Force, approached the American fighter with skepticism. The Mustang looked too delicate for combat, its sleek line suggesting a racing plane rather than a weapon of war.

But first flights revealed an aircraft unlike anything American pilots had experienced. The Laminar flow wing provided exceptional control response at all speeds while the Merlin engine delivered smooth power from sea level to 30,000 ft. Most importantly, the fuel consumption figures match theoretical predictions. Flying at economic cruise settings, the P-51 could remain airborne for over 6 hours while carrying external tanks.

The proof came on January 21st, 1944 when 12 Mustangs from the 354th Fighter Squadron attempted their first long range escort mission. The target was German aircraft factories at Usher Slaben, nearly 400 m inside enemy territory. Previous bomber raids to similar targets had suffered catastrophic losses when their P47 escorts turned back at the German border.

As the formation crossed into enemy airspace, Luftwafa controllers scrambled interceptors from bases across northern Germany. Messor Schmidt 109’s climbed toward the bomber stream, their pilots confident that any American fighters would soon reach their fuel limits and abandon the flying fortresses to their fate. Instead, they encountered P-51s maintaining formation alongside the bombers at 25,000 ft.

their laminar flow wings cutting through the thin air with minimal drag penalty despite the external fuel tank still attached. The engagement lasted 43 minutes. German pilots accustomed to fighting short-ranged American fighters over their own territory found themselves facing an opponent that could match their speed and altitude performance while operating hundreds of miles from home base.

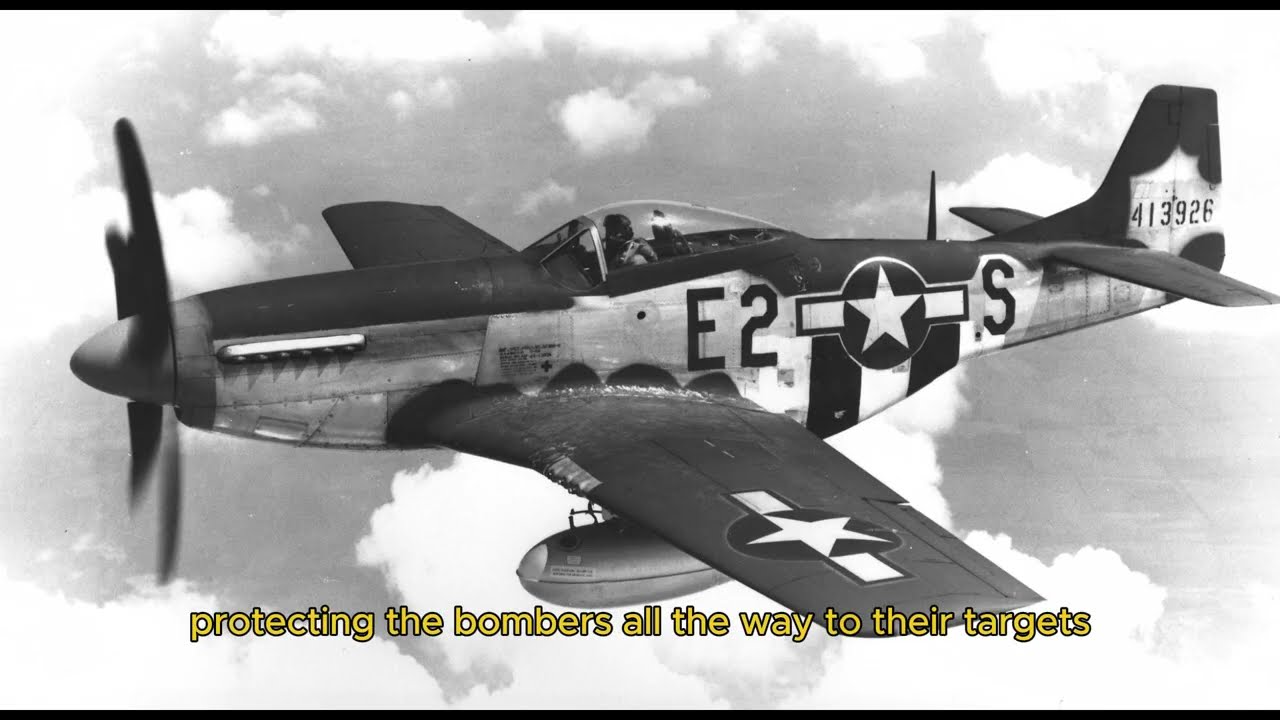

The Mustang’s combination of range and performance fundamentally altered the tactical equation of bomber escort operations. When the surviving Mustangs landed back at Debbdon that evening, they had proven Schmood’s stupid wing design in the most demanding test possible. The laminer flow air foil had carried American fighters deeper into German controlled airspace than ever before, protecting the bombers all the way to their targets and back.

The age of long range daylight bombing had begun, built on the foundation of an aerodynamic principle that conventional wisdom said would never work. The morning of March 6th, 1944 found Colonel Hubert Za studying weather reports at Boxed Airfield in Essex. Heavy overcast stretched across the English Channel with visibility dropping to less than 2 mi in scattered rain squalls.

Under normal circumstances, such conditions would ground any major bombing operation. But these were not normal circumstances. Intelligence reports indicated that German aircraft production had reached critical levels with Messer Schmidt factories working around the clock to replace losses from recent Allied raids. ZMA’s 56 fighter group had transitioned from P47 Thunderbolts to P-51 Mustangs just 3 weeks earlier.

The pilots, many of whom had flown over 100 combat missions in their beloved jugs, approached the sleek fighters with mixed emotions. The Thunderbolt could absorb tremendous battle damage and still bring its pilot home. The Mustang with its liquid cooled engine and lightweight construction seemed fragile by comparison, but fragility was relative when measured against performance.

The mission briefing revealed a target that would have been impossible for P47s to escort. Aircraft factories at Brunswick, deep in the heart of Germany, over 500 m from the English coast. The bomber stream would consist of 237 B-24s flying at 22,000 ft in tight defensive formations. Without fighter escort, German interceptors would tear the formation apart long before it reached the target area.

The Mustangs would provide that escort using a tactical innovation born from the laminer flow wings extended range capabilities. Rather than the traditional single-le escort mission, the P-51s would execute a relay system. The first wave would accompany the bombers to the German border, then hand off responsibility to a second group that had taken off 30 minutes later via a more direct route.

This second formation would escort the bombers to the target area while a third wave of Mustangs positioned themselves along the withdrawal route. Flight Lieutenant Bob Scott, flying his fourth mission in a P-51, found himself leading Blueflight in the second escort wave. His aircraft carried the standard armament of 650 caliber machine guns with 400 rounds per gun, plus two 75gal external fuel tanks that would be jettisoned before engaging enemy fighters.

The Merlin engine purred smoothly as his formation climbed through 15,000 ft. The laminer flow wings maintaining clean air flow despite the external stores. At 20,000 ft, Scott’s radio crackled with reports from the first escort wave. German radar stations had detected the incoming formation and Luftwafa controllers were scrambling interceptors from bases across northern Germany.

The first wave of Mustangs had already encountered probing attacks from Messersmidt 109s, but the real test would come when the bombers reached the heavily defended industrial area around Brunswick. The handoff occurred exactly as planned with Scott’s formation taking position alongside the bomber stream just as the first escort wave turned for home.

The P-51 spread into a defensive screen with flights positioned at different altitudes to counterattacks from above and below. The bombers droned onward at their steady 160 mph, their defensive gunners scanning the sky for the first signs of enemy fighters. The attack came without warning.

30 Faul Wolf 190s dove out of the sun, their radial engines screaming as they plummeted toward the bomber formation at over 400 mph. The German pilots had timed their approach to catch the escort fighters out of position, expecting the Americans to be low on fuel and unable to pursue effectively. Scott rolled his Mustang into a vertical dive, pushing the throttle to full military power as he closed on the lead Faulk Wolf.

The laminer flow wing performed exactly as Edgar Schmood had predicted, maintaining control authority even as the airspeed indicator climbed past 450 mph. At this speed, the wings reduced drag became a decisive advantage, allowing the P-51 to accelerate faster than the heavier German fighter.

The engagement dissolved into a series of individual dog fights scattered across 20 m of sky. German pilots accustomed to fighting fuel limited American escorts over their own territory found themselves facing opponents who could match their performance while operating deep inside the Reich. The Mustang’s combination of speed, range, and firepower fundamentally altered the tactical balance of the engagement.

Major Wilhelm Steinbower, leading the German formation in his Faulolf 190 Anton 8, attempted to use his fighter superior roll rate to escape a pursuing Mustang. But the American pilot stayed with him through a series of violent maneuvers. The laminer flow wing providing stable gun platforms even during high G turns.

Steinbau’s fighter absorbed multiple hits from the P-51 650 caliber guns before rolling into an uncontrolled descent toward the German countryside below. The innovation that made such deep penetration missions possible extended beyond the wing design itself. North American’s engineers had incorporated the Meredith effect radiator duct which used high-speed air flow through the coolant radiator to generate additional thrust at cruising speeds above 300 mph.

This system actually provided a net thrust gain, effectively turning the cooling system into a small jet engine that improved overall aircraft performance. This seemingly minor detail became crucial during extended combat operations. While German fighters struggled with engine overheating during prolonged engagements, the Mustang’s cooling system actually became more efficient at high speeds, pilots could maintain full power settings for extended periods without risking engine damage, providing a significant tactical advantage during

the long flights required for deep escort missions. As the bomber formation approached Brunswick, Scott’s fuel gauges showed the mission’s critical moment had arrived. His external tanks were empty and had been jettisoned 20 minutes earlier, but the internal fuel supply remained adequate for another hour of combat.

Operations plus the return flight to England. This endurance, impossible with conventional wing designs, allowed the escort fighters to remain with the bombers through their bomb run and initial withdrawal. The German response intensified as the formation crossed the target area. Fresh squadrons of interceptors rose from airfields around Hanover and Magnabberg.

Their pilots determined to prevent another successful Allied raid on their aircraft factories. But the mathematics of aerial combat had shifted decisively in favor of the attackers. Where previous escort missions had required American fighters to turn back before reaching such heavily defended targets, the Mustangs maintained their protective screen throughout the most dangerous phase of the mission.

When Scott’s formation finally handed off escort duties to the third wave of P-51s and turned for home, they had proven the strategic value of Schmood’s revolutionary wing design. The bombers had reached their target with minimal losses, delivered their ordinance accurately, and begun their withdrawal under continuous fighter protection.

The age of deep penetration daylight bombing had become operational reality. Built on the foundation of an air foil that maintained laminer air flow 500 m from home base. By May 1944, the numbers told a story that German high command could no longer ignore. Allied bomber losses over heavily defended targets had dropped from 26% to less than 4% in just 3 months.

The difference was measured not in improved armor or defensive firepower, but in the presence of American fighters maintaining formation alongside the flying fortresses deep into the Reich. Intelligence reports from surviving Luftvafa pilots, described encounters with P-51s over Berlin itself, a operational impossibility that had become routine reality.

General Adolf Galland, commander of German fighter forces, studied the tactical reports with growing alarm. His pilots were encountering American escorts at distances that exceeded every known performance parameter of Allied fighters. The P47 Thunderbolt, despite its robust construction and heavy armament, could barely reach the Rurer Valley with meaningful fuel reserves.

The P38 Lightning had better range, but suffered from compressibility problems at high altitude that made it vulnerable to experienced German pilots. Yet here were detailed combat reports describing Mustangs engaging German interceptors over targets 500 m from their English bases, maintaining high-speed combat maneuvers for extended periods, then escorting the bomber formations all the way back to the Channel Coast.

The tactical mathematics of air superiority had shifted so dramatically that Gallen found himself repositioning entire fighter groups to counter threats that previously would have been impossible. The proof lay in the mission logs accumulating at 8th Air Force headquarters in England. On May 8th, 358 B17 flying fortresses had attacked aircraft factories at Brunswick with the loss of only 12 bombers, a casualty rate that would have been inconceivable without continuous fighter escort.

The Mustang groups reported engaging over 100 German interceptors during the 6-hour mission, destroying 37 enemy aircraft while losing only eight P-51s. These numbers represented more than tactical success. They demonstrated the strategic revolution enabled by Schmud’s laminar flow wing design. Each successful deep penetration mission degraded German aircraft production capacity while preserving Allied bombing strength for future operations.

The cumulative effect was creating what intelligence analysts termed a death spiral in Luftvafa capabilities. Declining production combined with increasing pilot losses that could not be replaced at sustainable rates. Colonel Don Blakesley, now commanding the fourth fighter group, had witnessed this transformation firsthand during his transition from Spitfire operations with the Royal Air Force to longrange escort missions in P-51s.

The tactical flexibility provided by the Mustang’s extended range allowed his pilots to execute combat profiles that would have been suicidal in shorter ranged fighters. Instead of defensive escort formations tied closely to bomber streams, the P-51s could range ahead of the main force, clearing German interceptors from the approach routes before they could organize coordinated attacks.

The wing design’s efficiency extended beyond simple fuel consumption. During combat operations at maximum power settings, the laminer airflow characteristics maintained control authority even during violent maneuvering that would have stalled conventional air foils. Pilots reported that the P-51 remained controllable at air speeds approaching 500 mph.

Performance levels that allowed them to pursue German fighters through diving attacks that previously would have been impossible. This capability became decisive during the massive air battles over Berlin in March and April 1944. German defenders attempting to preserve their remaining experienced pilots had adopted tactics that emphasized hit-and-run attacks followed by high-speed withdrawals to secondary airfields.

The strategy worked effectively against P47 escorts which lacked the fuel capacity to pursue German fighters beyond the immediate target area. But Mustang pilots could maintain pursuit over hundreds of miles, following German formations back to their bases and engaging them during vulnerable landing approaches. Major George Prey, flying with the three 52nd Fighter Group, destroyed six German fighters during a single mission by exploiting this tactical advantage.

His P-51’s fuel reserves allowed him to remain over enemy territory for nearly 3 hours, far longer, than any German pilot expected American fighters to operate. The strategic implications extended beyond individual combat encounters. German fighter groups found themselves unable to concentrate their forces effectively because Mustang formations could appear anywhere within a 500m radius of English bases.

Luftwafa controllers accustomed to predicting American fighter coverage based on known fuel limitations discovered their tactical planning had become obsolete overnight. Edgar Schmud monitoring combat reports from his engineering office in Englewood found validation for every controversial design decision that had shaped the P-51 program.

The wing’s maximum thickness positioned at 50% cord length was maintaining laminar air flow under combat conditions that would have generated turbulent boundary layers on conventional air foils. Even more significantly, the NCA 66 series profile was delivering its promised 20% drag reduction across the full spectrum of operational altitudes and air speeds.

The numbers proved the wing’s effectiveness with brutal clarity. Standard combat formations of 12 P-51s were consuming fuel at rates that allowed six hours of flight operations, including one hour of maximum power combat maneuvering. This endurance enabled tactical profiles that fundamentally altered the strategic balance of the daylight bombing campaign.

American bomber crews who had faced near certain destruction during deep penetration missions just months earlier now flew to Berlin with casualty rates lower than training operations. German production statistics reflected the cumulative impact of continuous escort coverage. Aircraft factory output had declined by 37% since January while pilot training programs struggled to replace losses that averaged 15 experienced aviators per week.

The Luftwafa’s tactical doctrine built around intercepting unescorted bomber formations during predictable portions of their flight profiles had become irrelevant when faced with fighters capable of maintaining protective screens throughout entire missions. By June 1944, the transformation was complete.

Allied bombers routinely struck targets throughout Germany with fighter escort from takeoff to landing. The laminer flow wing that ShmeD’s colleagues had dismissed as impractical theory had become the foundation of American air superiority over Europe. German interceptor pilots once confident in their ability to devastate undefended bomber streams now found themselves outnumbered and outranged by escorts that could pursue them to their home airfields.

The final proof came during Operation Overlord when over 1,000 P-51s provided air cover for the Normandy landings while simultaneously escorting bomber formations against targets throughout France and Germany. The tactical flexibility that enabled such diverse mission profiles had transformed the Mustang from a promising interceptor design into the dominant air superiority fighter of the European theater.

Schmud’s stupid wing had delivered exactly what its specifications promised, the ability to escort Allied bombers anywhere in German controlled territory and bring them safely home. The summer of 1944 brought a revelation that would have seemed impossible just 12 months earlier. American fighters were hunting German aircraft over their own airfields with impunity.

The transformation reached its symbolic peak on July 7th when Major George Prey led his P-51 formation directly over the Luftvafa’s primary training base at Lechfeld, destroying four aircraft on the ground and three more during their attempted takeoff. The mission required a round trip of over 800 m from England, demonstrating operational capabilities that redefined the boundaries of tactical aviation.

Edgar Schmud received detailed combat reports at his North American Aviation Office. Each document validating design decisions that had seemed reckless when first proposed. The Laminar flow wing was performing beyond even his optimistic projections, maintaining its aerodynamic advantages under conditions that would have defeated conventional air foils.

Pilots were reporting stable gun platforms during high-speed pursuits, precise control response during violent combat maneuvers, and fuel consumption rates that enabled tactical profiles impossible with any other fighter design. But the true measure of the P-51’s impact lay in the strategic transformation of the European Air War.

German aircraft production, which had peaked at over 4,000 units per month in early 1944, had collapsed to fewer than 1500 by August. The continuous presence of long range escort fighters had made daylight bombing operations sustainable at loss rates that preserved Allied air strength while systematically destroying German industrial capacity.

General Henry Arnold, commanding the Army Air Forces, found himself revising strategic assumptions that had governed American air doctrine since Pearl Harbor. The original plan for defeating Germany through strategic bombing had accepted catastrophic loss rates as inevitable during deep penetration missions.

Planners had calculated that destroying German war production would require sacrificing hundreds of bomber crews in unescorted raids against heavily defended targets. The Mustang’s operational radius had rendered these calculations obsolete. Bomber formations now routinely struck targets throughout the Reich with casualty rates lower than operational training missions.

The strategic bombing campaign, once limited by unsustainable losses, had become a war of attrition that Germany could not win. Every successful mission degraded enemy capabilities while preserving Allied strength for future operations. Colonel Hub Zama transferred to command the 479th Fighter Group after his success with Mustang operations witnessed the psychological impact of long range escort capability on both sides of the conflict.

American bomber crews who had faced near certain death during missions beyond fighter range just months earlier now displayed confidence that bordered on routine. They understood that P-51s would accompany them throughout their missions, providing protection during the most vulnerable phases of flight. German pilots faced the opposite transformation.

Luftvafa interceptor tactics had relied on engaging unescorted bomber formations during predictable portions of their flight profiles, typically during the final approach to heavily defended targets. The constant presence of American fighters had eliminated these tactical opportunities. forcing German pilots to accept combat under conditions that favored their opponents.

The numbers told the story with devastating clarity. During the first week of August, Allied bombers flew over 3,000 sorties against targets throughout Germany, losing only 37 aircraft to enemy action. The same mission profiles would have cost over 400 bombers just 6 months earlier before continuous escort coverage became operational reality.

This statistical transformation reflected the cumulative impact of Schmood’s wing design on every aspect of air combat operations. The NACA 66 series air foil maintained its laminer characteristics under conditions that generated turbulent air flow on conventional wings, providing the efficiency necessary for extended range missions while preserving the performance required for air-to-air combat.

German pilots found themselves engaging opponents who could match their speed and altitude performance while operating hundreds of miles from home base. The tactical implications extended beyond individual engagements. German fighter groups traditionally concentrated near high-V value targets to maximize defensive effectiveness.

Discovered that Mustang formations could penetrate their defensive perimeters and engage them over their own airfields. The psychological impact of losing air superiority over home territory proved as damaging as the physical destruction of aircraft and facilities. Major Wilhelm Steinbower, one of the few experienced German pilots to survive extended combat against P-51 formations, reported that American escort fighters were operating with tactical flexibility that seemed impossible given known fuel limitations. His intelligence reports

described encounters with Mustangs that maintained high-speed combat for over an hour while positioned 400 m inside German territory, then provided continuous escort coverage during bomber withdrawal operations. These reports reflected the wing design’s performance under maximum stress conditions. During extended combat operations, the laminar flow characteristics prevented the boundary layer separation that would have increased drag on conventional air foils.

Pilots could maintain full military power settings for periods that exhausted German fighters operating over their own territory, fundamentally reversing the tactical advantages that had previously favored defenders. The strategic revolution reached its climax during the massive bombing campaign against German synthetic fuel production in late summer 1944.

These targets dispersed throughout the Reich and heavily defended by concentrated fighter forces represented the most challenging missions of the European Air War. Success required bomber formations to penetrate deep into enemy territory, maintain precise formation discipline during extended bomb runs, and survive coordinated attacks by hundreds of German interceptors.

The mission succeeded because P-51 formations could provide continuous protective coverage throughout operations that lasted over 8 hours. Mustang pilots reported engaging German fighters over targets near the Czech border, maintaining combat effectiveness during prolonged engagements, then escorting the bomber formations back to England with sufficient fuel reserves for defensive combat during withdrawal operations.

By September 1944, the transformation was complete. German fighter production had collapsed under continuous bombing pressure while pilot training programs struggled to replace losses that averaged over 200 experienced aviators per month. The Luftwafa’s defensive strategy once centered on concentrating fighter strength against predictable bombing patterns had become irrelevant when faced with escorts capable of maintaining protective screens throughout entire mission profiles.

Edgar Schmid’s controversial wing design had achieved exactly what his specifications promised, the ability to escort Allied bombers to any target in German controlled territory and return them safely to England. The laminer flow air foil that colleagues had dismissed as impractical theory had become the foundation of American air superiority over Europe, proving that revolutionary advances in aviation could emerge from challenging conventional wisdom about fundamental design principles.

The numbers validated every assumption underlying the NACA 66 series wing, demonstrating that aerodynamic efficiency could determine the outcome of strategic campaigns spanning entire continents. The autumn of 1944 witnessed the final collapse of German air defenses measured not in dramatic battles, but in the quiet efficiency of routine operations.

On November 2nd, 412 B17 flying fortresses struck synthetic oil refineries across central Germany, losing just six aircraft to enemy action. The mission required a round trip of over 900 miles with continuous fighter escort provided by P-51 formations that engaged German interceptors throughout the Reich without compromising their primary protective mission.

Edgars Schmud reviewing combat effectiveness reports in his California office found himself studying data that validated every controversial assumption underlying the laminer flow wing design. Combat pilots were reporting fuel consumption figures that matched wind tunnel predictions made 3 years earlier when the NACA 66 series air foil existed only as theoretical calculations on engineering drawings.

The wing was maintaining its aerodynamic advantages under operational conditions that exceeded the most optimistic test parameters. The strategic implications had become undeniable. German aircraft production, which had sustained the Luftvafa through 2 years of intensive combat operations, could no longer replace losses inflicted by continuous bombing under fighter escort.

Monthly output had fallen below 1,000 units by October, while pilot training programs struggled with fuel shortages that limited flight instruction to fewer than 20 hours per student. The Vermacht was losing the technological war that would determine Germany’s ability to continue fighting.

General Carl Spots, commanding strategic air forces in Europe, found himself executing bombing campaigns that would have been impossible with shorter ranged escort fighters. The operational flexibility provided by P-51 formations allowed Allied planners to strike targets throughout German controlled territory without accepting prohibitive loss rates.

Bombing missions that had required weeks of preparation and resulted in catastrophic casualties were becoming routine operations with predictable outcomes. The transformation was most evident in pilot morale statistics compiled by eighth Air Force medical officers. Bomber crews who had faced mathematical certainty of death or capture during unescorted deep penetration missions now reported confidence levels comparable to training operations.

They understood that Mustang formations would maintain protective coverage throughout their missions, engaging German interceptors before they could organize effective attacks against the bomber formations. Colonel Don Blakesley, leading the fourth fighter group through its transition to pure air superiority operations, witnessed the psychological impact of sustained fighter escort on German defensive tactics.

Luftvafa pilots, once confident in their ability to devastate unprotected bomber streams, had adopted increasingly desperate measures to avoid engagement with American escort fighters. German formations were abandoning coordinated attack patterns in favor of individual hit-and-run tactics that minimized exposure to P-51 guns.

These tactical changes reflected the cumulative impact of continuous combat losses among experienced German pilots. The Luftvafa’s training system designed to produce competent interceptor pilots through intensive instruction programs could not function effectively when fuel allocations limited flight training to subsistance levels. New pilots entering combat operations lacked the experience necessary to engage veteran American escort pilots on equal terms.

The wing design’s performance under extreme operational conditions had exceeded even schmood’s projections. Pilots were reporting sustained combat effectiveness during missions lasting over 7 hours with fuel reserves adequate for defensive engagement during withdrawal operations. The laminer flow characteristics prevented boundary layer separation that would have increased drag on conventional air foils, maintaining efficiency under conditions that defeated traditional wing designs.

Major George Prey flying his 150th combat mission on Christmas Day 1944 demonstrated the tactical capabilities that long range escort operations had made routine. His P-51 formation engaged German interceptors over targets near the Polish border, maintained air superiority during extended bomber operations, then provided protective coverage throughout the 4-hour return flight to England.

The mission required operational endurance that would have been impossible with any other fighter aircraft. German intelligence reports from this period revealed the strategic impact of continuous escort coverage on enemy planning assumptions. Luftwafa commanders accustomed to concentrating defensive fighters near high-V value targets to maximize effectiveness discovered that American formations could penetrate their defensive perimeters and engage them over their own airfields.

The tactical advantage of defending over friendly territory had been neutralized by opponents capable of maintaining combat effectiveness hundreds of miles from their home bases. The numbers documented the collapse of German air power with statistical precision. During December 1944, Allied bombers flew over 8,000 sorties against targets throughout the Reich, losing fewer than 60 aircraft to enemy action.

The same operational profile would have cost over 800 bombers just 12 months earlier before laminar flow wing technology enabled sustainable deep penetration missions. This transformation reflected more than tactical success. It demonstrated the strategic revolution that aerodynamic efficiency had brought to warfare itself.

The ability to maintain air superiority over enemy territory had shifted the fundamental balance between offensive and defensive operations. German forces found themselves unable to concentrate air power effectively because American fighters could appear anywhere within their operational radius without warning. Ed Horthy monitoring performance data from combat operations found validation for aerodynamic principles that had seemed theoretical when first applied to military aircraft design.

The NACA66 series wing was maintaining laminer air flow characteristics under combat conditions that generated turbulent boundary layers on conventional air foils. Pilots could execute violent combat maneuvers while preserving the fuel efficiency necessary for extended range operations. The wing’s effectiveness extended beyond simple drag reduction to fundamental changes in tactical doctrine.

American fighter pilots could engage German formations during their most vulnerable phases, particularly during takeoff and landing operations when enemy aircraft were constrained by fuel limitations and proximity to ground installations. The psychological impact of losing air superiority over home airfields proved as destructive as physical aircraft losses.

By January 1945, the strategic transformation was irreversible. German synthetic fuel production had collapsed under continuous bombing pressure, while aircraft factories struggled to maintain even minimal output under roundthe-clock Allied attacks. The Luftvafa’s defensive capabilities had been systematically eliminated through sustained operations that would have been impossible without longrange escort fighters.

Edgar Schmood’s laminer flow wing design had achieved strategic objectives that extended far beyond its original specifications. The NA 66 series air foil had enabled operational capabilities that fundamentally altered the balance of air warfare, proving that revolutionary advances in aerodynamic efficiency could determine the outcome of global conflicts.

The numbers validated every assumption underlying the controversial wing design, demonstrating that challenging conventional wisdom about fundamental engineering principles could transform the technological foundations of military power itself. The P-51 Mustang had evolved from promising interceptor to war-winning weapon system built on the foundation of an air foil that maintained laminar characteristics under conditions that defeated every competing Design.