Early 1943, Marine Corps headquarters, Quanico, Virginia. The weapon that would transform American snipers into the deadliest marksmen in the Pacific sat dismissed in a storage room labeled impractical for military use. John Unertle’s eight power scope had been designed for weekend shooting competitions, not warfare.

Its optics fogged in humidity. It required constant manual adjustments. Recoil knocked it out of alignment after every shot. Marine leadership called it a stupid civilian toy that would get their men killed. But Captain Edward Thomas saw something different. While generals argued that real Marines didn’t need to hide and pick off enemies from a distance, Thomas quietly issued the defective scopes to volunteers on Guadal Canal.

The conventional wisdom said close combat with rifles and bayonets won battles. That sniping was for cowards who couldn’t face the enemy. Then came the first reports from the jungle. Japanese officers dropping at distances no marine rifle was supposed to reach. Machine gun nests going silent before they could open fire. Enemy positions eliminated by invisible marksmen who struck like ghosts and vanished.

The stupid scope was doing something no one expected. Captain Edward Thomas stood in the dim light of the Marine Corps Armory at Quantico, turning the peculiar-l looking rifle over in his hands. The M1903A1 Springfield felt familiar enough. He’d carried variations of this weapon through his early Marine career, but the scope mounted on top looked like something a weekend hunter might bolt onto his deer rifle.

The Unertle 8 power optic stretched nearly 2 ft long, its black metal tube thick as a man’s thumb, with adjustment knobs that reminded Thomas more of a surveyor’s instrument than military equipment. Sir, with respect, that thing’s a joke. Said gunnery Sergeant Mike Kowalsski, watching Thomas examine the scope. The boys at Aberdine tested it last month.

Fogs up in any kind of humidity, loses zero every time you fire it, and the damn thing weighs more than a Thompson submachine gun. Thomas peered through the eyepiece, adjusting the focus ring. The magnification was impressive. He could read the serial numbers on rifles hanging across the armory.

But Kowalsski wasn’t wrong about the weight. The entire system tipped the scales at nearly 12 lb, three more than a standard Springfield. For Marines who already carried ammunition, rations, and equipment through jungle terrain, every ounce mattered. The scope’s creator, Johnle, had designed it for competitive target shooters who fired from stable benches at known distances.

His customers were civilians who spent weekends at rifle ranges, not soldiers crawling through mud under enemy fire. The scope’s external adjustment system required the shooter to physically move the crosshairs by turning knobs, a process that worked fine on a shooting range, but seemed impractical in combat. The tube didn’t even connect directly to the rifle.

It slid in a mounting system that allowed it to move freely during recoil, theoretically protecting the delicate optics, but creating another point of potential failure. General Shepard made his position clear at yesterday’s briefing. Kowalsski continued, “Marines fight with rifles and bayonets, face tof face, manto man. He thinks sniping is for cowards who can’t handle real combat.

” Thomas had been present at that briefing. Brigadier General Lemule Shepard, a decorated veteran of World War I and the current conflicts in the Pacific represented the old school of Marine thinking. Shepard believed in aggressive assault tactics, overwhelming firepower, and the kind of close quarters combat that had defined marine operations since the core’s founding.

To him, the idea of Marines hiding in trees or behind rocks, picking off enemies from hundreds of yards away violated everything the core stood for. The institutional resistance went deeper than one general’s opinion. Marine doctrine emphasized rapid movement, aggressive tactics, and the legendary Marine spirit that drove men to charge enemy positions rather than sit back and wait.

The core prided itself on producing warriors who could fight with rifle, bayonet, and bare hands if necessary. Sniping seemed contrary to this ethos, a passive, almost unsupporting way to wage war. But Thomas had read the early reports from Guadal Canal, and they painted a different picture of Pacific warfare. Japanese defenders weren’t lining up for traditional infantry charges.

They were dug into nearly invisible positions, camouflaged so effectively that Marines often couldn’t see them until it was too late. Enemy snipers were already operating with deadly effectiveness, picking off marine officers and sergeants from concealed positions. The conventional tactics that worked in Europe seemed inadequate against an enemy that specialized in camouflage, concealment, and long range precision fire.

Thomas picked up a folder containing test results from Aberdine Proving Ground. The military’s weapons testers had put the Unertle scope through standard evaluations, and their conclusions were damning. The scope failed humidity tests with condensation forming inside the tube after just 2 hours and 90% humidity, conditions common throughout the Pacific theater.

Accuracy testing showed the scope lost its zero after 20 rounds of firing, requiring constant readjustment. Drop tests revealed that even minor impacts could knock the crosshairs completely out of alignment. Look at this, Thomas said, pointing to a particular section of the report. They tested it like it was going to be a general issue weapon.

Standard rifle company tactics, rapid fire, movement, under fire. Of course, it failed those tests. Kowalsski leaned over to read the report. So, what are you thinking, sir? Thomas set the rifle down and walked to the window, overlooking the training ranges. Marines were conducting standard marksmanship training, firing at targets 200 and 300 yards away.

the typical engagement distances for which marine riflemen trained. But intelligence reports from the Pacific described a different kind of fighting on islands like Guadal Canal and Tulagi. The terrain created opportunities for much longer shots. Open ridge lines cleared landing beaches and sparse vegetation meant that skilled marksmen might engage targets at distances of 500 yd or more.

What if we’re asking the wrong question? Thomas said, “Instead of asking whether this scope can survive standard infantry tactics, what if we ask what kind of tactics would make the scope effective?” The concept wasn’t entirely new. The army had experimented with sniper programs during World War I with some success, but those efforts had been largely abandoned during the interwar period, dismissed as specialty tactics with limited application.

The Marine Corps had never formally embraced sniping, viewing it as inconsistent with their aggressive fighting spirit. Thomas picked up the rifle again, shouldering it and acquiring a sight picture on a distant target. The scope’s clarity was undeniable. At 8 power magnification, he could see details that were invisible to the naked eye.

A skilled marksman using the system could identify and engage targets at distances that put him well beyond the range of enemy return fire. Get me Lieutenant Colonel Bull from the First Division. Thomas told Kowalsski. I want to talk to someone who’s actually been in the jungle. Herbert Bull had commanded rifle companies on Guadal Canal and understood the tactical challenges of Pacific warfare better than most staff officers at Quanico.

If anyone could see the potential in an unconventional weapon system, it would be Bull. As Kowalsski left to place the call, Thomas continued examining the scope. Yes, it was heavy. Yes, it was fragile. Yes, it required constant maintenance and adjustment. But it also offered capabilities that no other weapon system in the Marine inventory could match.

The question wasn’t whether the Unertle scope met existing standards for military equipment. The question was whether those standards were adequate for the kind of war the Marines were actually fighting. Outside, the sound of rifle fire echoed across the training ranges as Marines practiced the conventional marksmanship that had served the core for decades.

But Thomas was beginning to envision a different kind of Marine marksman, one who used patience instead of aggression, precision instead of volume of fire. And the civilian gunsmith’s stupid scope to strike enemies who never saw death coming. The jungle on Guadal Canal in August 1943, felt like fighting inside a steam bath filled with razor blades.

Private first class Danny Kowalsski, no relation to the gunnery sergeant back at Quantico, crouched behind a fallen palm tree, sweat stinging his eyes as he tried to peer through the unertal scope mounted on his Springfield. The eight power magnification that had seemed so impressive on the rifle range at Camp Pendleton now showed him nothing but a green blur of vegetation, broken sunlight, and his own breath condensing on the inside of the scope tube.

“Can’t see a damn thing through this fog,” he whispered to Corporal Jim Martinez, who was positioned 10 yards to his left with a standard M1 Garand. They were part of a 12-man patrol from the second battalion, fifth marines, tasked with eliminating Japanese snipers who had been harassing supply convoys along the coastal road.

Martinez squinted through his iron sights at the treeine 200 yd ahead. At least you’ve got magnification. I’m shooting at shadows and hoping something falls down. The Unertle scope had arrived on Guadal Canal 3 weeks earlier along with Captain Thomas’ carefully worded orders to evaluate the tactical effectiveness of specialized optical equipment under combat conditions.

Six Marines had volunteered to carry the heavy unwieldy rifles drawn by Thomas’s promise that the scopes would give them a decisive advantage over Japanese marksmen. So far, the only thing the scopes had given them was frustration. Kowalsski adjusted the focus ring for the third time in 5 minutes, trying to find a setting that would cut through the humidity and dappled sunlight.

The scope’s external adjustment system designed for the controlled environment of a target range seemed to drift constantly in the heat and moisture of the jungle. Every morning, he had to rezero the weapon, firing precious ammunition to confirm that his point of impact matched his point of aim. Even then, the scope settings seemed to change throughout the day as temperature and humidity fluctuated.

The first time he tried to engage a target, a Japanese machine gunner positioned in a coconut palm 300 yd away, the bullet had struck 2 ft low and 6 in to the right of where the crosshairs indicated. By the time he’d calculated the correction and chambered a fresh round, the target had vanished into the green maze of the jungle canopy.

Movement 11:00. Martinez hissed, pointing toward a cluster of ferns near the base of a large banyan tree about 250 yards. Kowalsski swung the heavy rifle toward the indicated position. The inert scope’s field of view so narrow that he had trouble acquiring the target area. At 8 power magnification, finding and tracking moving targets required a completely different set of skills than the Marines had been taught.

Standard Marine marksmanship training emphasized quick target acquisition with iron sights, rapid fire, and engagement at ranges of 300 yards or less. The Unertle scope demanded patience, precision, and careful adjustment, qualities that seemed antithetical to marine training doctrine. Through the scope, Kowalsski could make out the distinctive shape of a Japanese type 99 rifle barrel protruding from the ferns.

The enemy sniper had chosen his position well, concealed in shadow with multiple escape routes. A conventional rifleman armed with an M1 Garand would have difficulty even seeing the target, let alone engaging it effectively at that range. Kowalsski studied his breathing and began the adjustment process he’d been practicing for weeks.

The Unertle’s external knobs required him to estimate range, wind speed, and elevation difference, then physically move the crosshairs to compensate. Unlike modern scopes with internal adjustment systems, the Unertle’s reticle moved independently of the scope tube, sliding on rails that were supposed to return to zero after each shot, but rarely did in practice.

He cranked the elevation knob clockwise, raising the crosshairs to compensate for bullet drop at 250 yd. The Pacific theat’s humid air affected ballistics differently than the dry conditions he trained in, and he’d learned through painful experience that his bullets dropped more than expected. The windage adjustment proved even more challenging.

Air currents in the jungle canopy created unpredictable eddies and gusts that could deflect a bullet several inches at moderate range. As Kowalsski fine-tuned his adjustments, the Japanese sniper shifted position slightly, the rifle barrel disappearing behind a curtain of vines. Standard marine tactics would have called for suppressive fire from the entire squad, spraying the target area with automatic weapons fire until the threat was neutralized.

But Thomas’ experimental doctrine required patience and precision. The goal wasn’t to drive the enemy away. It was to eliminate him permanently. Minutes passed in tense silence. Kowalsski’s arms began to cramp from holding the heavy rifle steady, and sweat dripped constantly onto the scope’s eyepiece, requiring him to wipe it clear every few seconds.

The Unertle’s design, intended for comfortable shooting from a bench rest, proved punishing when used from improvised field positions. The scope’s length made it difficult to maneuver in tight spaces, and its weight threw off the rifle’s balance, making it harder to hold steady during extended observation periods. Martinez was growing impatient.

Danny, we’ve got other positions to check. Maybe we should just lob some grenades over there and move on. The suggestion made tactical sense according to standard Marine doctrine. Speed and aggressive action had always been Marine strength. But Thomas’ orders were specific. used the scoped rifles to engage targets beyond the effective range of enemy return fire, demonstrating capabilities that conventional weapons couldn’t match.

The Japanese sniper reappeared, this time in a slightly different position 20 yard to the left of his original location. Through the unert, Kowalsski could see details that would have been invisible to the naked eye. the distinctive shape of the enemy’s helmet, the way sunlight reflected off the rifle’s bolt, even the fabric pattern of the sniper’s camouflaged uniform, the magnification that made target acquisition so difficult, also provided unprecedented clarity once the target was found.

Kowalsski made a final adjustment to his windage setting and settled the crosshairs on the center of the target’s torso. The Unertle’s crosshairs were thick and crude compared to modern optics, but at this range, they provided adequate precision. He controlled his breathing, relaxed his grip on the rifle stock, and began his trigger squeeze.

The Springfield’s firing pin struck the primer with its characteristic sharp crack, and the rifle bucked against Kowalsski’s shoulder. Through the scope, he watched the Japanese sniper jerk backward and disappear into the undergrowth. The Inertle’s recoil system had functioned as designed, allowing the scope tube to slide rearward and absorb some of the shock, but the crosshairs had still shifted slightly off their original position.

Martinez was already moving forward to confirm the kill, but Kowalsski remained in position, working to resero his scope for the next engagement. The process took nearly 10 minutes, time that would have been unacceptable in a conventional firefight, but was necessary for maintaining the precision that made the scoped rifle effective.

The dead Japanese sniper lay crumpled beside his Type 99 rifle, struck through the chest by Kowalsski’s bullet. It was a clean kill at a range that would have challenged even the best Marine marksman using iron sights. But as Kowalsski packed up his equipment and prepared to move to the next position, he couldn’t shake the feeling that he was fighting the scope as much as he was fighting the enemy.

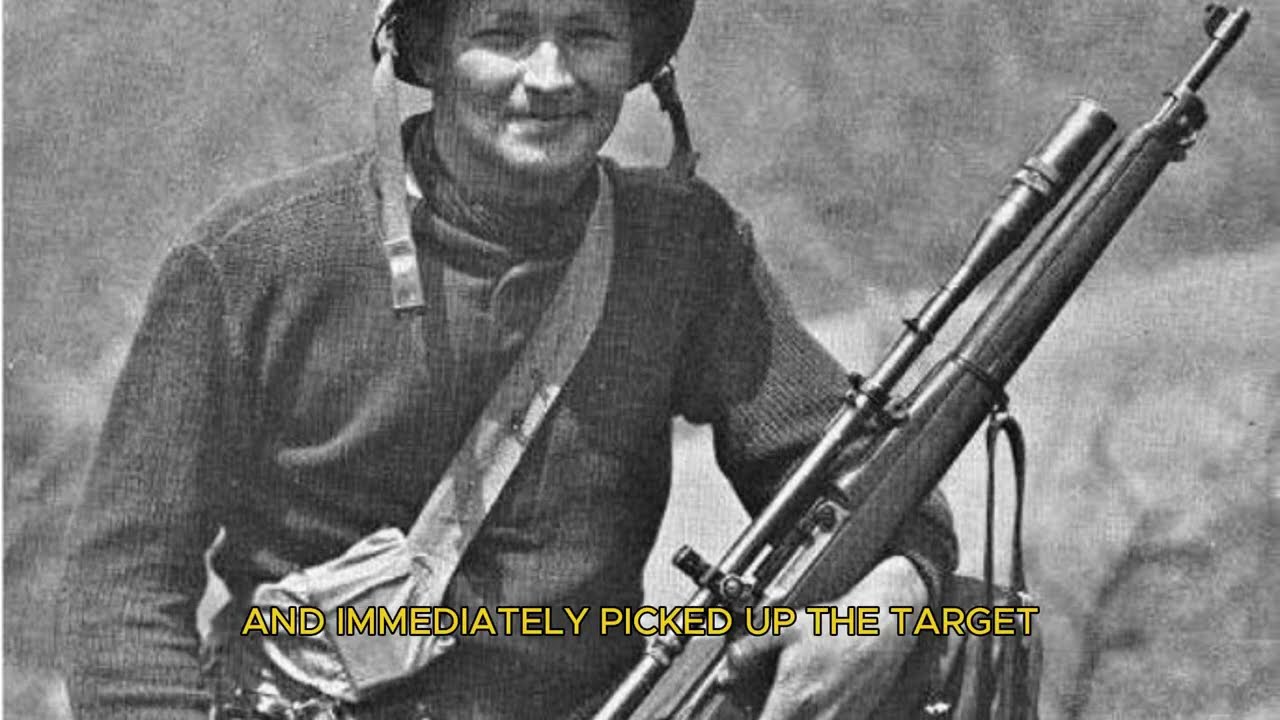

The coral air strip on Terawa stretched 1500 yardds across the narrow atal, a ribbon of crushed white stone that had cost the second marine division 3,000 casualties to capture. In November 1943, Sergeant Carlos Hathcock lay prone behind a pile of Japanese concrete and steel. His unertle equipped Springfield trained on a cluster of palm trees 800 yards across the lagoon.

The scope that had seemed so problematic in Guadal Canal’s jungle now revealed its true potential in the open terrain of the central Pacific. Target secondary from the left about halfway up, whispered his spotter, Lance Corporal Ted Williams, peering through binoculars at the distant tree line. Japanese observer with field glasses, probably calling in mortar fire on our engineers.

Hathcock adjusted the unertle’s focus ring and immediately picked up the target. At 8 power magnification, he could see the enemy soldier clearly, a Japanese naval infantryman in a green uniform, positioned in the fork of a coconut palm with an excellent view of the American positions. The man was methodically scanning the beach through his own optical equipment, occasionally pointing towards specific locations where marine construction crews were working to expand the airfield.

The SCA engagement range was far beyond what Marine riflemen had trained for during peace time. Standard doctrine called for engagements at 300 yd or less, distances where iron sights and volume of fire could overwhelm enemy positions. But the coral atoles of the central Pacific created entirely different tactical conditions.

Clear fields of fire extended for thousands of yards across flat lagoons and beaches, while elevated positions in palm trees provided observation points that could direct devastating artillery and mortar fire. Hathcock had learned to work with the unert scopees quirks rather than fight against them. Instead of cursing the external adjustment system, he developed a methodical process for range estimation and ballistic compensation.

The scope’s tendency to lose zero after firing had become manageable once he understood that the crosshairs would return to roughly the same position if he allowed the recoil system to function properly and avoided jarring the rifle unnecessarily. Range 800 yd. Wind may be 5 knots from the southeast, Hathcock murmured, cranking the elevation knob to raise his point of impact.

The inertle’s adjustment system still required manual calculation and physical movement of the crosshairs, but months of practice had made the process almost automatic. He’d learned to read the wind by watching palm frrons and coral dust, to estimate range by comparing target size to known references, and to compensate for the effects of heat shimmer rising from the coral surface.

The key breakthrough had come from embracing the scope’s original design philosophy rather than trying to force it into conventional marine tactics. John and Erdle had built his optic for precision shooters who took single, carefully aimed shots from stable positions in the open terrain of the central Pacific.

That approach proved devastatingly effective against Japanese positions that were beyond the range of conventional rifle fire. Williams adjusted his position slightly, keeping his binoculars trained on the target area while scanning for additional threats. Two more observers in the trees to the right.

Looks like they’re coordinating with someone on the ground. Through the unert scope, Hathcock could see what Williams was describing. The Japanese had established a sophisticated observation network with multiple spotters positioned to provide overlapping coverage of the American positions. Traditional marine tactics would have called for artillery or air strikes to eliminate the threat, but both options were unavailable.

The engineers needed uninterrupted time to complete the airirst strip, and any delay could jeopardize the entire Terawa operation. Hathcock settled into his firing position, using a sandbag to support the Springfield’s heavy barrel. The inertal scope’s weight, which had seemed like such a liability in the jungle, actually helped stabilize the rifle when firing from prepared positions.

The long tube reduced muzzle jump and provided a steady sight picture that made precision shooting possible at extended range. The first shot broke cleanly, the Springfield’s action cycling smoothly as the empty brass case ejected in a bright arc. Through the scope, Hathcock watched the Japanese observer tumble from his perch in the palm tree, the man’s field glasses spinning away to crash on the coral below.

The inertle’s crosshairs had shifted slightly during recoil, but not enough to require immediate adjustment for follow-up shots. Hit center mass, Williams confirmed. Target down. The other two are moving. Hathcock worked the bolt and chambered a fresh cartridge, swinging the rifle toward the second target position. The surviving Japanese observers were already reacting to their comrade’s death.

one of them scrambling higher into the tree canopy while the other began a rapid descent toward ground level. Both movements made them visible against the sky, silhouetted targets that the unert scope could track with deadly precision. The second shot came 30 seconds later, catching the climbing observer as he tried to reach a higher vantage point.

The bullet struck him in the torso, the impact spinning him around the palm trunk before he fell 40 ft to the coral surface. The third Japanese soldier abandoned his position entirely, sliding down the tree trunk and disappearing into the undergrowth at the base of the treeine. Williams swept the area with his binoculars, looking for additional threats.

That’s all I can see from here, but there’s probably more observers further inland. The engagement had lasted less than 5 minutes, but its tactical significance extended far beyond the elimination of three enemy soldiers. Hathcock had demonstrated that skilled marksmen armed with precision optics could dominate terrain that had previously been controlled by whoever held the high ground.

Japanese observers who had felt secure in their elevated positions 800 yd from American lines were now vulnerable to accurate rifle fire. More importantly, the psychological impact was already becoming apparent. Japanese soldiers who had watched their comrades fall to invisible marksmen were abandoning exposed positions and seeking deeper concealment.

The mere presence of American snipers was forcing changes in enemy behavior, disrupting observation networks and communication systems that depended on clear lines of sight across the ATL’s open terrain. Captain Thomas arrived at Hathcock’s position 20 minutes later, accompanied by Lieutenant Colonel Bull and a small group of staff officers.

They’d been monitoring the engagement from the command post, tracking its progress through radio reports and direct observation. Outstanding work, Sergeant Thomas said, examining the inert scope while Hathcock cleaned his rifle. What’s your assessment of the equipment’s performance in this terrain? Hathcock considered the question carefully, sir.

It’s like the scope was made for this kind of fighting. clear fields of fire, stable shooting positions, targets at extended range. The magnification lets us identify threats that iron sights couldn’t even see, and the precision is good enough to make first round hits at distances that put us well outside enemy rifle range. Bull nodded, making notes on a clipboard.

How does this compare to the jungle fighting on Guadal Canal? Night and day, sir. In the jungle, the scope’s magnification was almost a disadvantage. too much detail, too narrow a field of view, constant problems with condensation and glare. But out here with 800 to,200 yards of clear observation, it’s like having a completely different weapon system.

Thomas exchanged glances with bull. Both officers understood the implications of what they were witnessing. The Central Pacific campaign would feature dozens of similar atoles, each offering the same combination of clear fields of fire and elevated Japanese positions. If American snipers could systematically eliminate enemy observers and communications personnel before conventional assault forces landed, it could fundamentally change the tactical balance of amphibious warfare.

As the group prepared to return to the command post, Hathcock made a final adjustment to his scopes zero, preparing for the next engagement. Across the lagoon, Japanese soldiers were undoubtedly watching through their own optics, trying to identify the source of the deadly, accurate fire that had eliminated their observation posts.

But the Unertle scope’s range advantage meant that Hathcock could see them long before they could see him. A tactical revolution that was just beginning to reshape the war in the Pacific. The ridge line on Okinawa rose 300 ft above the Shuri Valley. Its rocky face scarred by weeks of artillery bombardment and honeycombed with Japanese cave positions that had resisted every conventional assault.

Staff Sergeant Carlos Hathcock crouched in a shell crater 50 yards below the crest, studying the enemy fortifications through his Unertle scope while mortar rounds exploded in the valley behind him. It was April 26th, 1945, and the First Marine Division had been stalled on this same ridge system for 18 days.

Count 12 visible firing ports in that section alone, Hathcock told Captain Thomas, who had crawled forward to observe the sniper operations personally. Japanese have interlocking fields of fire covering every approach. Machine guns, mortars, probably anti-tank guns in the deeper caves. Thomas raised his field glasses and studied the cliff face, seeing nothing but broken rock and occasional wisps of smoke from concealed positions.

How can you identify specific weapons through that scope? Hathcock adjusted the Unertle’s focus and pointed to a dark opening 60 yard up the ridge. See that rectangular shadow about halfway up? That’s a type 92 machine gun position. You can tell by the muzzle brake configuration and the way they’ve arranged the camouflage netting.

Different weapons have different signatures when you know what to look for. The transformation in sniper tactics had accelerated dramatically during the Okinawa campaign. What had begun as experimental use of civilian competition scopes had evolved into a systematic program of precision marksmanship that was reshaping marine infantry operations.

The Unertle equipped rifles were no longer curiosities carried by volunteers. They had become specialized tools wielded by carefully selected marksmen who understood both the equipment’s capabilities and its tactical applications. Hathcock had personally trained 43 Marine snipers during the past 18 months, passing along hard one lessons about ballistics, camouflage, fieldcraft, and the mental discipline required for precision shooting under combat conditions.

The scope that had once seemed impossibly fragile and complex was now maintained and operated by Marines who understood its engineering principles and tactical potential. Target movement 2:00 from the machine gun nest called Corporal Williams, now serving as Hathcock’s primary spotter. Japanese officer with a sword looks like he’s coordinating defensive positions.

Through the eight power scope, Hathcock could see the figure Williams had identified, a Japanese army captain moving between cave entrances, apparently inspecting defensive preparations. The man carried the traditional katana that marked him as an officer, and his movement suggested someone with significant authority over the cave complex.

Eliminating him could disrupt Japanese coordination and create confusion in their defensive network. The range was approximately 400 yardds, well within the unert scope’s effective envelope, but complicated by the steep upward angle and unpredictable wind currents created by the ridg’s rocky face. Hathcock had learned to read environmental conditions that affected long range shooting, temperature inversions that bent light and altered apparent target positions, humidity changes that affected powder burn rates and bullet trajectory, and the complex

air currents that swirled around elevated terrain features. Wind’s tricky up there, Williams observed, watching dust devils form and dissipate among the rocks. Maybe 8 knots from the southeast, but it’s gusting and changing direction. Hathcock nodded, already calculating the ballistic solution.

The Unertle’s external adjustment system, once viewed as a liability, had proven invaluable for making rapid corrections based on observed conditions. Unlike internal adjustment scopes that required tools or complex dial systems, the Unertle allowed immediate changes to elevation and windage settings without taking the rifle off target.

He cranked the elevation knob to compensate for the upward angle and bullet drop at 400 yd, then made a preliminary windage adjustment based on his reading of the air currents. The scope’s crosshairs moved smoothly on their rails, settling into a position that would theoretically place his bullet on target. But theory and practice often diverged in combat conditions, and Hathcock had learned to trust his instincts as much as his calculations.

The Japanese officer paused at the entrance to a large cave, apparently giving instructions to soldiers inside. Through the unertal scope, Hathcock could see enough detail to read the man’s body language and predict his movements. The magnification that had once seemed excessive for military applications now provided tactical intelligence that was impossible to obtain through conventional observation methods.

Hathcock controlled his breathing and began his trigger squeeze, applying steady rearward pressure while maintaining his sight picture. The Springfield fired with its characteristic sharp crack, the sound echoing off the ridge face and drawing immediate response from Japanese positions.

Machine gun fire swept across Hathcock’s general area, forcing him to duck below the crater rim while bullets snapped overhead. “Hit center mass,” Williams reported, watching through binoculars as the Japanese officer collapsed at the cave entrance. “Target down, but they’re really stirred up now.” The response confirmed what Marine commanders had suspected for months.

Japanese forces were acutely aware of American sniper operations and viewed them as a significant threat. The elimination of key personnel at extended range had become a priority concern for enemy commanders who were dedicating substantial resources to counter sniper operations and protective measures for their leadership.

Captain Thomas crawled closer to Hathcock’s position as the immediate enemy fire subsided. How many confirmed kills with that scope system now, Sergeant? Hathcock worked the bolt and chambered a fresh round while considering his answer. 47 confirmed, sir, but that’s not really the important number. It’s about disrupting their command structure, forcing them to change their tactics, making them afraid to move around their own positions.

The psychological impact of precision sniping had become as important as the direct casualties inflicted. Japanese commanders who had once moved freely between positions were now confined to deep bunkers and underground tunnels. Communication networks that depended on visual signals and personal contact were disrupted by the constant threat of accurate rifle fire from invisible marksmen.

Even when snipers weren’t actively engaged, their presence influenced enemy behavior and tactical decisions. Thomas studied the ridge through his field glasses, noting how the landscape had been transformed by weeks of combat. What’s your assessment of the scope’s durability under these conditions? We’re planning to expand the sniper program significantly for the invasion of Japan.

Hathcock ran his hand along the Unertle’s tube, checking for damage from the morning’s activities. It’s held up better than anyone expected, sir. The external adjustment system actually makes it easier to maintain under field conditions. If something gets knocked out of alignment, we can usually fix it without sending the whole rifle back to the armory.

The biggest issue is keeping the lenses clean in this dust and humidity. The conversation was interrupted by movement in the Japanese positions. Through his scope, Hathcock could see soldiers emerging from caves to retrieve their fallen officer, exposing themselves to observation and potential engagement. The systematic elimination of enemy leadership was forcing the Japanese to take risks they would have avoided under normal circumstances.

Williams spotted additional targets. Multiple personnel moving between positions, probably trying to establish new command arrangements. Looks like our shot really disrupted their organization. Hathcock settled back into his firing position, already identifying priority targets among the exposed enemy soldiers.

The inertal scope that had once been dismissed as a stupid civilian toy was now the centerpiece of a tactical revolution that was changing the nature of infantry combat. Each precisely placed shot demonstrated capabilities that conventional weapons could never match, proving that sometimes the most unlikely solutions produced the most dramatic results.

The armory at Camp Pendleton in September 1945 looked nothing like the skeptical storage room where Captain Thomas had first examined John Unertle’s civilian scope 2 and 1/2 years earlier. Rows of M1903 A4 rifles lined the weapon racks, each one topped with the distinctive black tube of an Unertle 8 power scope, and Marines moved between the workbenches with the quiet efficiency of craftsmen who understood their tools intimately.

The stupid scope had not only survived the Pacific War, it had become the foundation of an entirely new military specialty. Master Sergeant Carlos Hathcock stood before a class of 26 Marine recruits holding one of the scoped rifles while explaining the ballistic principles that governed precision shooting at extended range.

The young Marines listened with the intense focus of students who knew their instructor had used the same equipment to eliminate 93 confirmed enemy targets across four major Pacific campaigns. What had once been experimental equipment operated by volunteers was now standard issue for Marines selected through rigorous testing and training programs.

The scope’s not magic, Hathcock told his students, running his hand along the unert’s familiar contours. It’s a tool that amplifies your existing skills while demanding new ones you probably never thought about. Anyone can learn to shoot accurately at 200 yards with iron sights. This system lets you engage targets at 600 yardd or more, but only if you understand wind, temperature, humidity, light conditions, and about 50 other variables that don’t matter much at close range.

The transformation had been gradual but profound. After Okinawa, Marine Corps leadership had commissioned a comprehensive study of sniper operations throughout the Pacific theater, analyzing every engagement where unertile equipped rifles had been employed. The results were undeniable. Precision marksmen had eliminated key enemy personnel at ranges beyond conventional rifle effectiveness, disrupted command and control networks, provided detailed reconnaissance of enemy positions, and created psychological effects that influenced

Japanese tactical decisions across entire battle areas. Lieutenant Colonel Herbert Bull, now serving as the Marine Corps’s senior adviser on specialized weapon systems, walked among the students as Hathcock demonstrated proper scope adjustment techniques. Bull had been one of the earliest advocates for the sniper program and his detailed combat reports had provided the documentation necessary to overcome institutional resistance within the core.

Sergeant Hathcock explain to the class how scope maintenance differs between jungle and open terrain. Bull instructed, knowing the answer would illustrate lessons learned through bitter experience across multiple environments. Hathcock set the rifle on the workbench and began disassembling the scope mounting system. In the jungle, your biggest enemies are humidity and condensation.

The original unertal design wasn’t sealed against moisture. So, we learned to carry desicant packets and clean the internal surfaces every morning. But in open terrain like the atoles, dust and heat shimmer become the major problems. You’re constantly cleaning the external lenses and learning to read mirage effects that can throw your shots off by several inches.

The students took notes as Hathcock demonstrated techniques that had been developed through trial and error during actual combat operations. The core had initially expected to use the scoped rifles exactly like conventional infantry weapons, but experienced snipers had discovered that precision shooting required entirely different tactical approaches.

Patience replaced aggression, careful observation, supplanted rapid fire, and individual initiative became more important than unit coordination. Colonel Thomas, recently promoted after his success with the sniper program, entered the classroom carrying a thick folder of documents. His presence commanded immediate attention from the students who knew he had personally overseen the development of Marine sniper tactics from experimental concept to operational reality.

Gentlemen, I have the final combat effectiveness report from Pacific Fleet Headquarters, Thomas announced, opening the folder and scanning the summary pages. Our sniper teams achieved a documented kill ratio of 1.7 enemy soldiers per round fired, compared to approximately 1,800 rounds per enemy casualty for conventional rifle companies.

More significantly, post-war interrogations of Japanese prisoners revealed that sniper operations forced major changes in enemy tactics and significantly degraded their command effectiveness. The numbers represented validation of principles that had once seemed contrary to Marine Corps doctrine. The institution that prided itself on aggressive assault tactics had discovered that carefully applied precision could achieve results far beyond what volume of fire could accomplish.

Japanese commanders who had planned to coordinate defensive operations from elevated observation posts were forced underground, communicating through runners and written messages instead of direct visual contact with their units. Bull added context that the official reports couldn’t fully capture. What the statistics don’t show is how enemy behavior changed when they knew American snipers were operating in their area.

Japanese soldiers stopped moving during daylight hours, abandoned elevated positions, and avoided exposing themselves for the time necessary to aim and fire their own weapons effectively. The psychological impact multiplied the tactical effect of each successful engagement. Thomas walked to the window, overlooking the rifle ranges where Marines were conducting standard marksmanship training.

The program will expand significantly as we prepare for future operations. Intelligence estimates suggest that any invasion of the Japanese home islands would have required neutralizing thousands of defensive positions in mountainous terrain ideal for precision shooting. The atomic bombs made that invasion unnecessary, but the lessons we’ve learned will shape marine operations for decades to come.

Hathcock picked up one of the newer Unertle scopes. Its design refined based on combat feedback, but still recognizable as the civilian competition optic that had started the entire program. The scope itself never really changed much, he observed. What changed was how we learned to use it. John and Nerdle built this thing for target shooters who fired from benches at known ranges under controlled conditions.

We figured out how to make it work from shell craters and tree branches in 100° heat with Japanese machine gunners shooting back. The irony wasn’t lost on any of the Marines present. The military had initially rejected the Unertle scope because it failed to meet conventional standards for infantry weapons. Its weight, complexity, and fragility seemed to violate every principle of military equipment design.

But those same characteristics, when properly understood and exploited, had created capabilities that conventional weapons couldn’t match. As the class concluded, students filed past the weapon racks, each one examining the scoped rifles with new understanding. The young Marines who would carry these weapons into future conflicts understood that they were inheriting more than just precision optics.

They were becoming part of a tactical revolution that had transformed a civilian gunsmith’s weekend shooting accessory into one of the most effective weapon systems of the Pacific War. Thomas remained in the classroom after the students departed, studying reports from the European theater, where army snipers had achieved similar success using different equipment and tactics.

The principles were universal, but the applications varied with terrain, enemy behavior, and operational requirements. The inertal scope had proven its worth in the specific conditions of Pacific warfare, but the larger lesson was about institutional willingness to embrace unconventional solutions when traditional methods proved inadequate.

Outside, the sound of rifle fire echoed from the training ranges as a new generation of Marines learned to shoot with iron sights at conventional distances. But in specialized classrooms and on advanced ranges, other Marines were mastering the patience, precision, and tactical thinking that would define military sniping for generations to come.

The stupid scope had become a foundation for capabilities that would outlast the war that created