The heat in old Tucson was brutal, even at 7:00 in the morning. It was late June of 1959, and the cast and crew of Rio Bravo had been filming in the Arizona desert for almost 6 weeks. By noon, the temperature often climbed to 115°. Every scene felt miserable. Actors baked in heavy old-style costumes, and crew members dragged bulky equipment across dusty roads that hadn’t even existed a few months earlier.

Dean Martin sat inside his trailer, looking over the day script pages and trying to ignore the sweat already soaking his shirt collar. Someone had set up a small fan near his chair, but it barely helped. He’d been working on the movie with Howard Hawks and John Wayne for about a month and a half now.

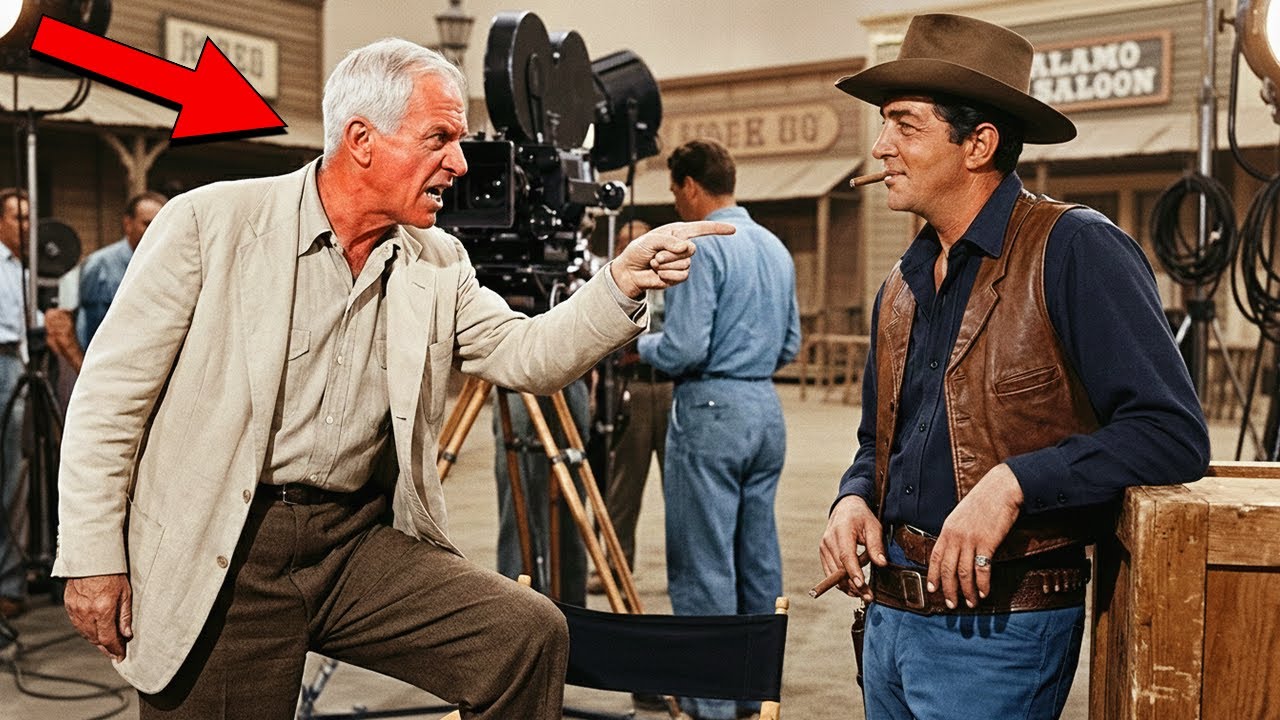

Filming was going fine on the surface, but something had been bothering him almost from the start. Hawks treated him like he wasn’t really there. Not in an obvious way, not in a way most people would notice, but Dean noticed. Hawks would talk through scenes with Duke, breaking down emotions and motivations, discussing what the character was thinking and feeling.

Then he’d turn to Dean and simply tell him where to stand and what line to say. Hawks asked Duke’s opinion on camera angles and setups, but never asked Dean anything beyond basic movement. Dean was playing Dude, a former drunk trying to earn back his self-respect. It was one of the most layered characters in the movie, but Hawks directed him like he was some background cowboy there only to support Duke and make the star shine brighter.

A knock on the trailer door pulled Dean out of his thoughts. It was the assistant director, Tom, a stressed out young guy who looked exhausted from trying to keep the shoot on track. Mr. Martin, we’re ready for you. Saloon scene. Dean grabbed his hat and followed Tom into the harsh sunlight. The saloon set was about a hundred yards away.

From the outside, it looked like a real western building. Inside, it was fully dressed and ready for the camera, but it offered no relief from the heat at all. It felt like an oven. The crew was adjusting the lights. Duke and Hawk stood near the bar, deep in conversation. Dean walked over and waited. Neither of them looked at him.

The thing is, Hawks was saying, “Your character sees this differently than anyone else. You’re not worried about the gang. You’re worried about whether your friends will hold up when the shooting starts. That’s the real tension.” Duke nodded, thinking it over. “So, when I look at dude, I’m not seeing my deputy.

I’m seeing someone I’m not sure I can trust.” “Exactly. That doubt is what makes the scene work.” Dean cleared his throat. “Should I be part of this talk since it’s about how your character sees mine?” Hawks glanced at him, surprised, like a chair had suddenly spoken. “Just play the scene as written, Dean,” he said. “Hit your marks. Say your lines.

Duke and I will handle the deeper stuff.” “But if Duke doesn’t trust, dude,” Dean said. “Shouldn’t I know that so I can show that awareness?” “Don’t overthink it,” Hawks replied. “You’re a drunk trying to prove himself. Focus on that. The rest will work itself out.” Then Hawks turned back to Duke, ending the conversation. They kept talking about character depth and meaning while Dean stood there feeling like he’d been pushed to the side. The scene itself went smoothly.

Dean hit his marks, delivered his lines, and felt he did solid work. Hawks called cut after two takes and moved on without giving Dean any of the detailed notes he’d been giving Duke all day. At lunch, Dean sat with Ricky Nelson, the young singer who was new to acting. Ricky seemed relieved to have someone to talk to.

Hawks is kind of scary, Ricky said, poking at his sandwich. I never know if he likes what I’m doing. At least he talks to you, Dean said. He treats me like I’m just here to stand next to Duke and make him look good. You really think that? I don’t think it. I know it. Watch him.

Every creative question goes to Duke. The rest of us are just pieces he moves around. Ricky shifted in his seat. Maybe that’s just how he works. Duke’s the star. I’ve worked with directors who treat everyone like partners, Dean said. Hawks treats Duke like a partner and everyone else like hired help. Dean finished eating and headed back to his trailer.

Before he reached it, Hawks called out, “Dean, got a minute?” They walked away from the crew to a quieter spot. Hawks pulled out cigarettes, offered one, and they both lit up. “I just wanted to check on you,” Hawk said. “Make sure you’re comfortable.” “I’m fine. You seem annoyed. Is something bothering you?” Dean thought for a moment.

“I don’t feel like I’m being used right. Dude could be a really strong character, but I’m not getting much direction.” Hawks took a long drag. “That’s because you don’t need direction. You’re a pro. You show up and do the job. I don’t need to guide you through everything. It’s not about guidance,” Dean said. “It’s about working together, making the character better.

” “The character’s good enough,” Hawk replied. “You’re playing a drunk deputy. This isn’t Shakespeare.” Dean felt anger rise, and it had nothing to do with the heat. “So, what am I to you, Howard?” he asked. “Just someone filling space?” Hawk smiled, but there was no warmth in it. I’ll be honest, Hawk said. I’ve been making movies for 30 years.

I’ve worked with Bogart, Grant, Cooper. I know how to use stars. Duke’s a star because I know how to shape him. Half his best performances came from me. He paused, then looked Dean straight in the eye. But you? You’re just an extra in this picture. The word hung between them. Extra. I’m second build, Dean said quietly. I’m in almost every scene.

That’s a strange definition of extra billing doesn’t mean anything. I could put a trained monkey second build if the studio wanted it. What matters is who the camera loves, who the audience comes to see. They’re coming for Duke. You’re here to support him, to make him look good. That’s your job.

And if you can’t accept that, maybe we’ve got a problem. Dean dropped his cigarette and crushed it under his boot. We don’t have a problem, Howard. I’ll do my job. Just don’t expect me to be grateful for being treated like furniture. He walked away before Hawks could respond. His mind already racing ahead to what this meant.

He was stuck on this picture for another month of shooting, being directed by someone who saw him as expendable, as just another hired hand there to make John Wayne look good. Fine. He’d finish the picture professionally, collect his paycheck, and then he’d show Hawks exactly how wrong he was about who audiences came to see. The rest of the Rio. Bravo.

Shoot was professional, but cold. Dean did his job. gave solid performances and didn’t cause any problems, but he also didn’t go out of his way to socialize with Hawks or participate in the after hours discussions about the film that Duke and Howard frequently had. Hawk seemed fine with this arrangement.

He got what he needed from Dean performance-wise and didn’t appear bothered by the lack of creative collaboration. “Duke tried to play Peacemaker a few times, inviting Dean to join their discussions, but Dean politely declined.” “Nothing personal, Duke,” Dean said during one such invitation. and I just don’t feel like being somewhere I’m not really wanted.

Duke looked uncomfortable. Howard didn’t mean anything by what he said. That’s just how he talks. Maybe, but he meant it. And I’m not interested in pretending otherwise. The film wrapped in late August. There was a small party on the last day of shooting. The usual routine of speeches and thank yous and promises to work together again.

Hawks made a point of praising Duke’s performance, calling it one of his finest. He thanked the crew for their hard work. He mentioned Ricky’s natural screen presence. Dean’s name came up exactly once in a list of cast members Hawks was obligated to acknowledge. If you’re invested in this story, please take a moment to hit that like button.

On the flight back to Los Angeles, Dean’s manager met him at the airport with news about potential projects. There were several offers on the table. The usual mix of comedies and musicals and light dramas that studios thought Dean was suited for. “Anything interesting?” Dean asked as they drove toward Beverly Hills.

Depends on what you’re looking for. There’s a musical at Fox that could be good. Comedy at Paramount that’s basically a guaranteed hit. Nothing too challenging, but solid work. What about westerns? His manager looked surprised. You want to do another western? I thought you said the Rio Bravo shoot was miserable.

The shoot was fine. The director was the problem, but I liked playing Dude. I think I could do something interesting in that genre if I found the right project. Westerns are mostly John Wayne’s territory these days. He’s got that market locked down. Then maybe it’s time someone challenged him for it.

His manager pulled the car over, turning to look at Dean directly. What’s going on? This doesn’t sound like you. Dean stared out at the Los Angeles traffic, trying to articulate what had been building in him since that conversation with Hawks in Old Tucson. I’m tired of being seen as the song and dance man who occasionally acts. I’m tired of directors treating me like I’m lucky to be on their set.

Howard Hawks told me I was just extra, that my job was to make Duke look good. And you know what? He’s not the first person to see me that way. Studios see me that way. Critics see me that way. Everyone thinks I’m just coasting on charm and getting by on the minimum effort. So, what a you want to do about it? I want to find a project that proves them all wrong.

Something that shows I can carry a film, that I can be more than just support for someone else. and I want it to be a western because that’ll make the point even clearer. His manager thought about this. There might be something. I heard about a script making the rounds adaptation of a novel called The Sons of Katie Elder.

Story about four brothers coming together after their mother’s death. It’s being set up at Paramount, but they haven’t locked in the lead yet. Who’s interested? Kirk Douglas, maybe Bert Lancaster. The studio wants a big name, someone who can anchor an ensemble cast. Get me that script and set up a meeting with the producers. Dean, they’re not going to consider you for the lead.

No offense, but you’re not known for carrying dramatic westerns. Then let’s change what I’m known for. The script for The Sons of Katie Elder arrived 2 days later. Dean read it that evening, and by the time he finished, he knew this was exactly what he’d been looking for. The story centered on John Elder, the oldest of four brothers, a gunslinger with a reputation who returns home for his mother’s funeral and discovers corruption and conspiracy that his brothers are too young or too naive to handle.

It was a role with real depth, requiring both toughness and vulnerability, action and emotion. It was also exactly the kind of role that Howard Hawks would have said Dean couldn’t handle. The meeting with Paramount was set for the following week. Dean prepared for it like he’d prepared for nothing else in his career, reading and rereading the script, developing a complete vision for who John Elder was and how he’d play him.

When he walked into the producers’s office, three men were waiting for him. The lead producer, Arthur Jacobs, and two executives from Paramount’s Western Division. They all looked mildly confused about why Dean Martin was there. “Gentlemen, thanks for taking the meeting,” Dean said, settling into a chair across from them.

I hear you’re putting together Katie Elder and haven’t locked your lead yet. I want to play John Elder. The three men exchanged glances. Jacob spoke first. Dean, we appreciate your interest, but John Elder is a pretty far cry from the kind of roles you usually play. This is a serious dramatic western, not a comedy with songs.

I know what it is. I also know I can play it better than anyone else you’re considering. Better than Kirk Douglas? better than Bert Lancaster. Yes, because they’ll play it like every other western they’ve done. Tough guy, stoic hero, all the usual beats. I’ll play it like a real person, someone who’s tired of violence, who wants to protect his brothers, but knows his reputation makes that harder, who’s carrying guilt over leaving them when they were young.

I’ll make him human, not just heroic. One of the executives leaned forward. You’ve done one western in your career, Dean. Rio, bravo. And in that picture, you played a drunk deputy supporting John Wayne. That’s your only experience in this genre. Then you haven’t seen the final cut yet because my performance in Rio Bravo is going to surprise a lot of people, including Howard Hawks, who thought I was just extra.

Jacobs raised an eyebrow. Hawk said that to you. In those exact words, said I was just there to make Duke look good, that I was basically furniture on the set. And you’re telling us this because because I want you to understand what I’m fighting against. Every studio, every director, they see me as the comedian, the singer, the personality, not the actor.

Hawks made that very clear. And I’m done accepting that verdict. I want this role because it’ll prove I can do more. And I’ll make you a deal. What kind of deal? Cast me as John Elder. If the picture flops, if audiences don’t respond, I’ll take half my usual salary. But if it succeeds, if it makes money and people like what I do with the character, then I want my full rate plus profit participation.

The room went quiet. Jacobs exchanged long looks with the two executives. “You’re that confident,” Jacob said finally. “I’m that confident because I know what I can do, even if most of Hollywood doesn’t believe it yet.” The executives asked him to wait outside while they discussed. Dean sat in the reception area for 20 minutes, watching assistants rush past with scripts and memos, wondering if he’d just talked himself into or out of the biggest opportunity of his career.

Finally, Jacobs came out. We want you to do a screen test. If it works, if we believe you can carry this, we’ll consider the deal you proposed. When? Next week, we’ll set up some key scenes. See how you handle the material. Dean stood and shook Jacobs’s hand. You won’t regret this. The screen test was scheduled for the following Friday.

Dean spent the week preparing obsessively, working with an acting coach he’d never needed before, practicing the scenes until he could do them in his sleep, thinking through every nuance of how John Elder would move and speak and react. The test itself was just Dean, a camera, and a reader feeding him lines. No elaborate sets, no costumes beyond a basic western shirt and hat, just raw performance.

And Dean delivered. He poured everything he’d been holding back on the Rio Bravo set into these few minutes of film. All the frustration of being underestimated, all the determination to prove his doubters wrong, all the skill he’d accumulated over 25 years of performing channeled into creating a character who felt livedin and real.

When he finished, the room was silent. Jacobs and the executives had watched from behind the camera, and their expressions were unreadable. “We’ll be in touch,” Jacob said. Two days later, Dean’s manager called with the news. They want you. Full deal. The salary arrangement you proposed, everything. Congratulations. You’re the lead in a major Western.

Dean allowed himself a moment of satisfaction. Then asked the question that really mattered. When do we start shooting? Late spring, probably April or May of next year. Gives them time to assemble the rest of the cast and finalize the script. Good. That gives me time to get ready. You’re already ready, Dean.

You just proved that with the screen test. No, I’m competent. I want to be great. I want this performance to be so good that nobody ever questions whether I can handle dramatic material again. The period between being cast and starting production felt endless. Dean turned down several other projects, wanting to focus entirely on preparing for Katie Elder.

He worked with the acting coach, studied other westerns to understand the genre’s conventions so he could subvert them, and collaborated with the screenwriters to deepen his character. Meanwhile, Rio Bravo was released in March of 1959. The reviews were generally positive with most critics, praising the chemistry between Duke and Dean, the sharp script, and Hawk’s direction.

But what really caught the industry’s attention was the box office. Rio Bravo became a massive hit, eventually earning over $10 million against its $1.8 million budget. It was one of the highest grossing westerns of the decade, and the critical response to Dean’s performance was particularly notable.

Variety called him surprisingly effective as the alcoholic deputy. The Hollywood Reporter wrote that Martin brings unexpected depth to what could have been a onenote character. The New York Times said, “Martin’s performance is the film’s secret weapon, providing emotional weight that balances Wayne’s stoic heroism.

” Dean kept the reviews, not out of vanity, but his ammunition. When people questioned whether he could carry Katie Elder, he’d point to the Rio Bravo notices and ask why they doubted him. The person who most notably didn’t comment on Dean’s performance was Howard Hawks. The director gave several interviews about Rio Bravo, praising Duke extensively.

But when asked about the supporting cast, he’d give generic responses about everyone doing professional work. Dean heard through mutual friends that Hawks had been surprised by how well Dean came across in the final film. How audiences responded to Dude’s character arc. Apparently, Hawks had said something to the effect of, “I guess Dean had more in him than I thought.

” It was as close to an admission of being wrong as Hawks was likely to give. Dean didn’t need an apology. The success spoke for itself. Production on The Sons of Katie Elder began in late April of 1960. Dean arrived in Durango, Mexico, where most of the filming would take place and immediately established himself not as a supporting player, but as the leader of the production.

The director, Henry Hathaway, had a reputation for being tough and demanding, but he and Dean clicked immediately. Haway respected actors who came prepared and had strong ideas about their characters, and Dean was both. I’ve worked with a lot of leading men, Hathaway told Dean during their first meeting. Some of them think their job is to show up and look good.

But the best ones, they understand they’re setting the tone for the entire production. You seem like you understand that. I do. And Henry, I want to make something clear from the start. I’m not here to coast. I’m here to make the best western I possibly can. If I’m screwing up, tell me.

If you’ve got a better idea for a scene, I want to hear it. I want us to collaborate, not just you giving orders and me following them. Haway smiled. I think we’re going to get along just fine. The shoot was long and physically demanding, but Dean thrived in it. He did most of his own stunts, worked through injuries, and maintained a professional atmosphere on set that kept morale high even during the difficult Mexican location shooting.

But more importantly, he gave a performance that exceeded even his own expectations. John Elder was tough but vulnerable, violent but reluctant, protective but flawed. Dean made him feel like a real person dealing with an impossible situation, not just a western archetype. The supporting cast, which included Earl Hollowan, Michael Anderson Jr.

, and Martha Hire, all deferred to Dean’s leadership. He’d created an environment where everyone felt free to contribute ideas and take risks with their performances. It was everything his experience on Rio Bravo hadn’t been. Instead of being treated like furniture, Dean was the center of the production, the person everyone looked to for guidance and inspiration.

When shooting wrapped in September, Haway pulled Dean aside. That was one of the best experiences I’ve had making a picture, and a lot of that is because of you. The way you carried yourself, the way you treated the crew and the other actors that set the tone for everything. Thanks, Henry.

I learned from watching good directors and bad ones. Figured out what worked and what didn’t. Howard Hawks is a good director. Howard Hawks is a great director who treats his actors like props unless their name is John Wayne. There’s a difference. Haway laughed. I heard you two had some tension on Rio Bravo. He told me I was just extra, that my job was to make Duke look good. So yeah, we had tension.

Well, after he sees this picture, he’s going to realize how wrong he was. The Sons of Katie Elder was released in June of 1965 after extensive post-prouction and a careful marketing campaign. Paramount had decided to position it as a major event western, giving it a wide release and a substantial advertising budget. The reviews were strong.

Critics praised the performances, the direction, and the script’s balance of action and character development. Dean’s performance, in particular, received enthusiastic notices. The New York Times, Martin anchors the film with a performance that’s both tough and tender, creating a fully realized character rather than a western cliche.

Variety. Dean Martin proves he’s more than a song and dance man with a richly textured performance as John Elder. This is star making work. The Hollywood Reporter. Martin commands every scene he’s in, demonstrating dramatic range that will surprise those who’ve underestimated him. And if you’re still watching, please consider subscribing to see more stories like this.

But the real validation came from the box office. The Sons of Katie Elder opened to massive numbers playing in theaters across the country to sold out crowds. It earned over $2 million in its first week. Extraordinary numbers for a western. By the end of its theatrical run, the film had grossed over $12 million, making it one of the highest grossing westerns of the decade and one of Paramount’s biggest hits of the year.

Dean’s Gamble had paid off spectacularly. He’d not only proven he could carry a dramatic western, he delivered a massive commercial success that outperformed most of the John Wayne vehicles released in the same period. The profit participation he’d negotiated meant he earned substantially more than his usual salary.

But more importantly, he’d fundamentally changed how Hollywood saw him. He wasn’t just the comedian or the singer anymore. He was a legitimate leading man who could open a major film. The first person to call and congratulate him was John Wayne. Dean, just saw Katie Elder. Hell of a performance. You should be proud. Thanks, Duke.

Means a lot coming from you. I heard Howard gave you some trouble on Rio Bravo. didn’t treat you right. He had his opinions about what I was capable of. I proved him wrong. You sure as hell did. You know, I’m putting together another western with some friends interested in playing opposite me again as equals this time, not as my drunk deputy. Dean smiled.

Send me the script. If it’s good, I’m in. The call he didn’t get was from Howard Hawks, but Dean heard through the grapevine that Hawks had seen Katie Elder and been impressed despite himself. Supposedly, he’d told someone that he’d misjudged Dean’s capabilities, that he should have given him more creative input on Rio Bravo.

It was as close to an apology as Dean was likely to get, and he’d take it. The success of Katie Elder led to more substantial dramatic offers. Directors who’d never considered Dean for serious roles suddenly wanted to work with him. Studios that had pigeonhold him as a lightweight entertainer now saw him as someone who could anchor prestige projects.

Dean was selective about what he accepted, turning down several lucrative offers that would have been easy paydays in favor of projects that challenged him and built on what he’d established with Katie Elder. He did eventually work with John Wayne again on several westerns over the following years, but the dynamic was different.

They were peers now, equals, both stars in their own right rather than star and supporting player. And whenever they’d be on set together, whenever a director would favor Duke’s input over Dean’s, Dean would politely but firmly assert himself. He’d learned from the Hawks experience that allowing yourself to be diminished even on someone else’s set was a mistake.

Some directors responded well to this, appreciating Dean’s collaborative approach. Others found him difficult, preferring actors who just followed direction without questioning it. Dean didn’t care which category a director fell into. He knew his worth now and he wasn’t going to pretend otherwise to make anyone’s job easier. Years later, at a retrospective screening of Rio Bravo, someone asked Dean about working with Howard Hawks.

The questioner clearly expected diplomatic praise for one of cinema’s great directors. Instead, Dean was honest. Howard is talented, no question. But he had definite ideas about who deserved creative respect and who didn’t. I wasn’t in his inner circle, so I got treated like a supporting player, even though I had the second biggest role in the picture.

That taught me a valuable lesson about not letting directors define your worth for you. Some people say you hold a grudge against Hawks. I don’t hold grudges, but I don’t forget being told I’m just extra when I know I’m more than that. Hawks was wrong about me and my career since Rio Bravo has proven it. That’s not holding a grudge.

That’s just stating facts. The interviewer pushed further. If Hawks asked you to work with him again, would you? Dean considered this. Depends on the project. If it was good enough, if the role was substantial enough, maybe. But I’d make very clear from the start that I expect to be treated as a creative collaborator, not furniture.

If he couldn’t agree to that, then no amount of money or prestige would make me say yes. Howard Hawks died in 1977 without ever publicly acknowledging that. He’d underestimated Dean Martin. But people who knew both men said Hawks had privately admitted later in life that Dean’s career trajectory had surprised him. He’d expected Dean to remain a personality, a singer who occasionally acted, but never developed real dramatic chops.

Instead, Dean had become a legitimate film star who could carry prestigious projects and deliver performances that critics took seriously. It bothered Hawks that he’d been so wrong about someone’s potential. He prided himself on his eye for talent, his ability to identify and develop stars. Missing on Dean Martin, dismissing him as just extra was a rare failure in an otherwise stellar career of talent assessment.

Dean heard about this third hand from someone who’d had dinner with Hawk shortly before his death. Supposedly, Hawks had been discussing his regrets, the projects that didn’t work out, and the opportunities he’d missed. “I should have listened to Dean more on Rio Bravo.” Hawks had apparently said he knew that character better than I gave him credit for.

If I had collaborated with him instead of just directing him, the performance would have been even better. When Dean heard this story, his response was simple. Too little, too late. But I appreciate the sentiment. The truth was that Dean had stopped needing Hawk’s validation years earlier. The success of Katie Elder and the career it launched had been all the validation he needed.

He’d proven that he was more than just extra. He’d proven he could make stars himself, starting with his own career transformation from singer, comedian to serious actor. And he’d done it all by refusing to accept someone else’s limited vision of what he was capable of. That was the real lesson of the Hawks experience.

Not that Hawks was a bad director or a bad person, but that even talented, experienced people can be wrong about others potential. And when they are, the only response is to prove them wrong through your work. Dean had done exactly that. And in doing so, he’d created one of the most successful second acts in Hollywood history.

The records that Katie Elder broke weren’t just box office numbers. They were assumptions about what Dean Martin could do, limitations that others had placed on him, boundaries that he’d refused to accept. Every ticket sold, every positive review, every offer for substantial dramatic roles that came after, they were all evidence that Howard Hawks had been catastrophically wrong when he’d called Dean just extra.

Dean Martin wasn’t extra. He was essential, not just to Rio Bravo, though that film benefited enormously from his performance, but to the entire landscape of 1960s Hollywood. He’d shown that performers could reinvent themselves, that labels and categories could be transcended, that determination and talent could overcome even the most dismissive assessments.

And he’d done it all while maintaining his dignity, his professionalism, and his sense of humor about the absurdity of an industry that claimed to value talent while constantly underestimating it. That’s the real story of how Dean Martin’s next movie broke records. Not just the financial records, though those were impressive, but the records of what people thought he could do, what directors thought he was worth, what Hollywood believed was possible for a singer comedian who refused to stay in his lane.

Howard Hawks made stars like Duke. That was true, but Dean Martin made himself a star despite Hawk’s best efforts to relegate him to supporting status. And in the end, that was a much more impressive achievement. If this story inspired you, if it reminded you that other people’s limited vision doesn’t have to define your potential, please take a moment to like this video and subscribe to the channel.

These stories from Hollywood’s golden age teach us that success is often about refusing to accept the limitations others place on us and having the courage to prove the doubters wrong. Thank you for watching and thank you for believing in your own potential.