At 0200 hours on January 24th, 1943, Lieutenant Commander Richard Chickmer crouched in a slit trench on Guadal Canal, watching the United States Marine Corps get humiliated. Above him, the sky was a suffocating sheet of black velvet. There were no stars, no moon, and absolutely no hope of seeing what was killing them.

The only warning came from the unsynchronized drone of Japanese engines. It was a rhythmic grinding noise that sounded like a washing machine full of bolts echoing off the jungle canopy. The Marines called the pilot washing machine Charlie, a nickname that sounded funny in daylight but terrifying in the dark. Hmer watched as a single orange flare drifted down from the invisible aircraft, illuminating the airfield like a stage light. Seconds later, the ground shook.

High explosive bombs smashed into the runway, shattering parked fighters and shredding sleeping tents. The Japanese pilot was taking his time. He was flying slow, low, and loud. He was mocking them. Harmer gripped the edge of the trench until his knuckles turned white. As a fighter pilot, his entire existence was built on the concept of aggression.

You find the enemy, you dive on the enemy, and you kill the enemy. But tonight, he was just a spectator to his own destruction. Around him, anti-aircraft batteries erupted in a chaotic light show, pumping thousands of rounds into the empty sky. It was a waste of metal. The gunners were firing at noise.

They were trying to hit a single mosquito in a pitch black room with a sledgehammer, and they were missing every single time. The Japanese pilot didn’t even bother to evade. He just circled back for another pass, dropping bombs with the casual arrogance of a man who knew he was invisible. Hmer looked at the flight line where his squadron’s planes sat cold and silent.

In the daylight, those machines were predators. At night, they were nothing but expensive aluminum targets. The problem wasn’t a lack of courage. It was a lack of biology. The human eye is a predator’s tool, but only when the sun is up. The moment the sun dipped below the horizon, the Imperial Japanese Navy owned the Pacific.

For 20 years, while American pilots were practicing formation flying in sunny California, the Japanese were drilling in the dead of night. They selected men with exceptional night vision, drugged them to keep their pupils delated, and forced them to fly formation in total darkness until they could sense the ocean swells without seeing them.

By 1943, they were the undisputed masters of the night. They could launch torpedo attacks, coordinate bombing runs, and navigate hundreds of miles without a single photon of light. To the Americans, it felt like witchcraft. The Japanese Zero fighters would appear out of nowhere, slash through a bomber formation, and vanish before a single turret gunner could traverse his weapon.

Hmer knew that unless the Navy changed the laws of physics, they were going to lose the war one night at a time. The current strategy was pathetic. Search lights were worse than useless. The moment a ship turned one on, it became a giant beacon for every Japanese torpedo bomber within 50 mi.

The sound locators, giant acoustic ears meant to track engines, were too slow to keep up with modern aircraft. The Navy was desperate. They needed a way to see the invisible. They needed eyes that didn’t require light. Back in the States, a group of frantic engineers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology were working on a secret project that sounded like science fiction.

They called it airborne intercept radar. It was a technology that sent out pulses of radio waves and listened for the echo, painting a picture of the world on a small glowing green tube. But having the radar was only half the battle. They needed a machine fast enough to catch a Japanese fighter, but strong enough to carry the heavy, delicate electronics.

The engineers looked at the Navy’s inventory and pointed a trembling finger at the VA F4U Corsair. It was a decision that made every experienced pilot laugh in disbelief. The Corsair was already a monster. It was built around the massive Pratt and Whitney R2800 double Wasp engine, a power plant that swung a propeller spanning 13 ft across.

The plane was so overpowered that if a pilot jammed the throttle forward too fast on takeoff, the torque would flip the aircraft upside down and kill him before he left the ground. It had a nose so long that the pilot couldn’t see the runway in front of him. It bounced on landing.

It stalled one wing before the other. The Navy had already banned it from carrier decks, labeling it the Enson eliminator because it killed so many student pilots in broad daylight. Now the engineers wanted to take this unstable pilot killing beast and make it even harder to fly. To fit the radar, they couldn’t just shove it in the fuselage. There was no room.

They had to bolt a massive fiberglass pod onto the tip of the starboard wing. This pod was the size of a beer keg and weighed hundreds of pounds. It completely ruined the aerodynamics of the aircraft. It acted like a giant air bra on just one side, constantly pulling the plane to the right. To counter the weight, the mechanics had to rip out the machine guns from that wing, leaving the pilot with only three guns on the left.

This created a nightmare of asymmetry. When the pilot fired, the recoil would twist the plane violently to the left. When he flew straight, the radar pod dragged him to the right. and the engineers expected a human being to land this lopsided monstrosity on a moving ship in the middle of the ocean in total darkness.

When Hmer first saw the blueprints for the project affirm night fighter, he didn’t see a plane. He saw a suicide note written in aluminum. The radar set itself, the AIA unit, was a primitive collection of glass vacuum tubes, copper wire, and prayer. It was heavy, hot, and fragile.

A hard carrier landing could shatter the tubes like light bulbs. The display screen was a tiny 3-in circle buried in the cockpit instrument panel. To use it, the pilot had to bury his head inside a rubber hood, blocking out the rest of the world and stare at a flickering green dot while flying a 400 mph aircraft at treetop level.

If the pilot looked up for a second, he would lose the signal. If he trusted his inner ear, he would crash. He had to become a biological extension of the machine, ignoring his survival instincts and trusting a green smudge of light to tell him where the ocean ended and the sky began. The experts at the Bureau of Aeronautics were skeptical.

Actually, they were hostile. During the initial briefings, admirals openly scoffed at the idea of a night corsair. They argued that a single seat fighter pilot simply didn’t have the brain power to fly the plane, navigate, talk on the radio and operate a complex radar system simultaneously. The British Royal Air Force used two man crews for night fighting, one to fly, one to watch the radar.

They told Hmer that overloading a lone pilot with this much data would result in vertigo-induced water impact. In plain English, the pilot would get dizzy, flip over, and slam into the sea. They called the modified plane a suicide sled. They refused to clear it for carrier operations. They told Hmer to take his team to a land base and stay out of the Navy’s way.

Hmer didn’t care about the safety reports. He cared about the men burning to death in the water at Guadal Canal. He looked at the admirals and told them that the Japanese weren’t waiting for the perfect safety rating. He argued that the Corsair, for all its faults, was the only plane with the speed to catch a zero and the toughness to survive a cannon shell.

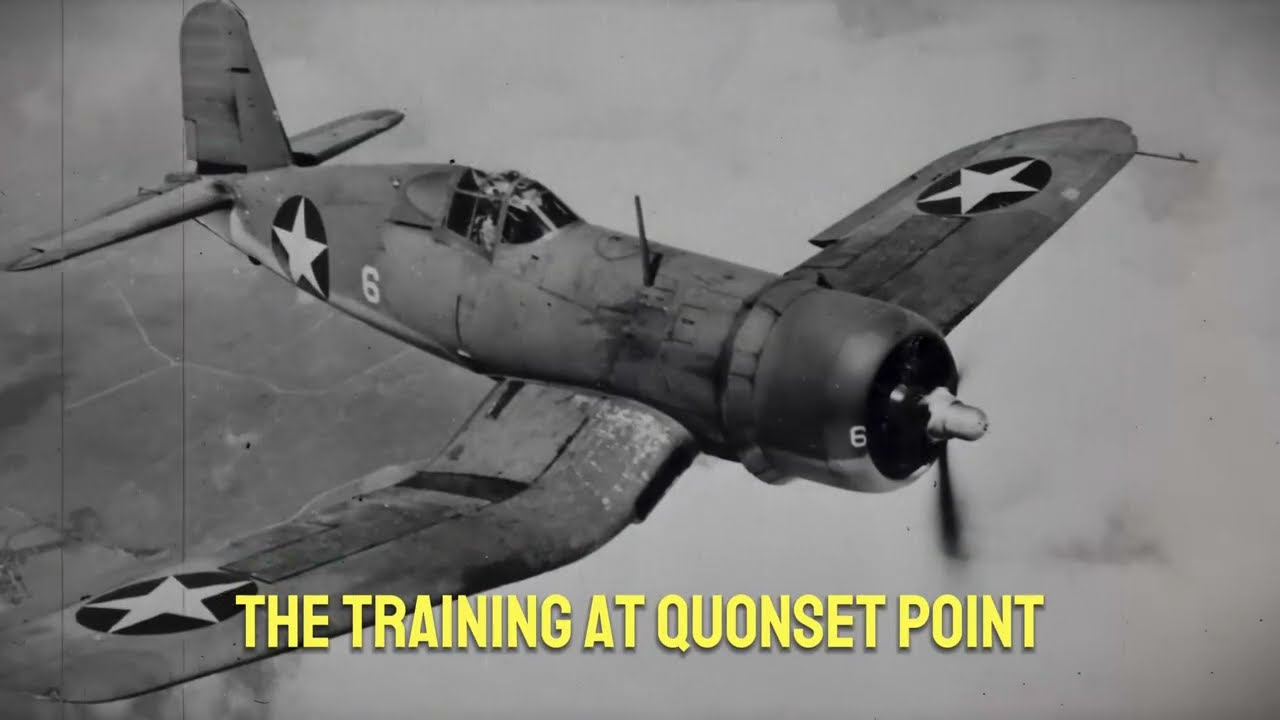

He accepted the command of VFN75, later redesated VFN101, a squadron of outcasts and guinea pigs. His mission was impossible. Take a plane that couldn’t land on a carrier, equip it with a radar that barely worked, and train a group of pilots to kill an enemy they couldn’t see. The training began in secret at Quonet Point, Rhode Island.

It was a place of biting cold and relentless wind far away from the prying eyes of the press. Hmer gathered his pilots, a mix of veterans and aggressive rookies, and told them the truth. He told them they were going to do things that the flight manual said were impossible. They weren’t just learning to fly at night.

They were learning to unlearn how to be human. A human relies on balance and sight. Hmer needed them to become machines. He ordered the mechanics to tape cardboard over the cockpits of their planes during daylight flights. He forced the pilots to take off, fly intercepts, and simulate attacks completely under the hood with nothing but that green glowing eye to guide them. It was terrifying.

The pilots called it flying inside a inkwell. The radar was crude. It didn’t give clear pictures. It gave blips, amorphous blobs of light that could be an enemy plane, a cloud, or a mountain. The closer you got to the target, the more the ground clutter interfered. The main bang, the pulse of the radar leaving the transmitter created a blind spot for the first 200 yd in front of the nose.

This meant that just as the pilot was about to shoot, the radar would go blind. He had to close the distance using the green dot, then look up at the last possible second to visually spot the enemy engine exhaust before pulling the trigger. It was a dance of death played out in seconds. But the biggest enemy wasn’t the Japanese. It was the equipment itself.

The vacuum tubes failed constantly. The vibration of the massive double wasp engine shook the solders loose. Every morning, the hangar deck looked like a radio repair shop exploded. Hmer’s men were using chewing gum, bailing wire, and electrical tape to keep the systems running. The experts laughed.

They said the maintenance hours were unsustainable. They said the F4U2 was a hanger queen that would never see combat. Hmer ignored them. He pushed his men harder. He knew that soon the Pacific sun would set and the washing machine Charlie’s would return. And this time he wanted to be waiting for them in the dark.

The transformation of the Corsair into a night predator was not a precise scientific evolution. It was a butchery of aerodynamics. To the naked eye, the F42 looked like it had grown a tumor. The radar scanner was housed in a bulbous white fiberglass pod mounted on the leading edge of the starboard wing. just outboard of the propeller ark.

It ruined the beautiful gullwing symmetry of the aircraft. Pilots who walked out to the flight line for the first time stopped and stared, convinced that the engineers had lost their minds. The pod disrupted the air flow so severely that the right wing generated less lift than the left.

It meant that from the moment the wheels left the ground until the engine shut down, the plane was trying to roll over and kill the pilot. To fly straight, the pilot had to hold constant exhausting pressure on the stick, fighting the machine for every mile of sky. Inside the cockpit, the situation was even worse.

The radar scope, a small cathode ray tube glowing with a sickly emerald light, was shoved into the main instrument panel, displacing the altimeter and airspeed indicators. To see it, the pilot had to bury his face in a rubber viewing hood that looked like a glamorous camera attachment from the 19th century. This was the scope. It was their god.

When a pilot was under the hood, he was effectively blind to the outside world. He was flying a 2,000 horsepower blender through pitch darkness, relying entirely on a flickering green line to tell him if he was about to slam into a mountain or an ocean. The mental strain was excruciating. A day fighter pilot had to be aggressive.

A night fighter pilot had to be schizophrenic. He had to fly the plane with his hands and feet while his mind lived inside the green tube, interpreting blobs of light as three-dimensional objects. Hmer pushed his men to the breaking point. The training at Quanet Point became a grim ritual of sensory deprivation. They launched into the Black Atlantic Knights when even the seagulls stayed grounded.

They practiced groundcontrolled intercepts where a radar operator on the ground would talk them onto a target. But the technology was in its infancy. The radios crackled with static. The radar sets overheated. The vacuum tubes, delicate glass bulbs that were never designed to withstand the brutal vibration of a carrier landing, shattered with depressing regularity.

The mechanics of VFN 101 became artisans of improvisation. They learned that the high voltage connections in the radar set would arc and short out in the salt air. The supply chain didn’t have waterproof seals, so the ground crews raided localarmacies. They bought boxes of latex prophylactics, condoms, and used them to waterproof the cable connectors.

It was the perfect absurdity of war. A multi-million dollar secret weapon kept operational by rubber contraceptives and electrical tape. But the biggest hurdle wasn’t the technology. It was the United States Navy. The admirals in Washington were terrified of the night Corsair. They looked at the accident reports of the standard daylight Corsair, the way it bounced on landing, the way the long nose blocked the pilot’s view, and they did the math.

They concluded that landing a destabilized radar heavy Corsair on a pitching carrier deck in the dark was simply a complicated way to commit suicide. They ordered Hmer to operate from land bases only. They wanted to turn his squadron into a defensive garrison force protecting islands after the fleet had moved on. Hmer refused to accept that.

He knew that if the night fighters were stuck on an island, they were useless. The war was moving across the Pacific at 20 knots. The fleet needed protection wherever it went, not just where it had been 2 weeks ago. He needed to prove that the suicide sled could operate from a carrier deck. He needed a ship. After months of badgering, pleading, and threatening, he got his chance aboard the aircraft carrier USS Enterprise.

The Big E was a legend, but her deck was just as hard and unforgiving as any other. The qualification trials were the moment of truth. Hmer approached the carrier at night. The ship nothing more than a darker shadow against the black water. He couldn’t see the horizon. He couldn’t see the waves. He could only see the tiny dim lights of the landing signal officer, the LSO, waving paddles at the stern.

The radar pod on his right wing dragged at the air, pulling the nose off center. Hmer had to crosscontrol the aircraft, fighting the torque and the drag, crabbing sideways toward the steel deck. The LSO had never landed a night fighter before. He was waving at a ghost. Hmer cut the throttle. The massive double Wasp engine popped and snarled.

The Corsair dropped like a stone, a characteristic trait of the heavy fighter. In the daylight, a pilot could judge the height and flare at the last second. At night, depth perception was a lie. Hmer had to trust the LSO and his own gut. He hit the deck hard. The olio struts compressed with a violence that rattled his teeth.

The hook caught the wire. The plane slammed to a halt, the tail rising ominously before settling back down. He had done it. He had landed the unlandable plane on a ship in the dark. The deck crew rushed out, terrified of the spinning propeller they couldn’t see, to unhook the wire. Hmer taxied forward, folding the wings.

The radar pod pointed up at the stars like an accusing finger. He had proven the concept, but the victory was bittersweet. The Navy agreed to deploy them, but they fragmented the squadron. Instead of a massive overwhelming force of knight fighters, they split Hmer’s team into small detachments of four or six planes, scattering them across the Pacific like spare change.

Hmer took his detachment to the USS Enterprise. Another group went to the USS Intrepid. They sailed west into the heat and the violence of the Central Pacific. The reality of combat hit them immediately. It wasn’t the glory of the news reels. It was a humid, corrosive grind. The tropical air was a death sentence for their electronics.

Fungus grew inside the radar scopes. The humidity caused short circuits that the condom fix couldn’t always stop. The pilots spent their days sweating in the ready room, trying to sleep while the day fighters launch strikes and their nights sitting in their cockpits, waiting for a call that might never come. The day fighter pilots, the sunsetters in their Hellcats, looked at the night corsairs with a mixture of pity and suspicion.

They didn’t understand the radar. They called it scope dope. They mocked the night pilots for sleeping all day, calling them vampires and cave dwellers. There was a cultural divide on the ship. The day pilots were the rock stars, flying in blue skies, racking up kills that could be filmed and verified. The night pilots were the weirdos in the corner, tinkering with glass tubes, speaking a language of megahertz and pulse width that no one else understood.

But the mockery stopped when the sun went down. At night, the fleet became a terrifyingly vulnerable place. The Japanese had realized that the American defenses were blind. They launched single bombers, the Bettis and Kates, to prowl around the task force. They would drop flares to illuminate the carriers, signaling submarines or massing for torpedo runs.

The gunners on the ships were jumpy. They would open fire at anything, often shooting at their own shadows. Into this chaos, Hmer and his men launched. The first intercepts were clumsy. The ground control would vector a Corsair toward a bogey, an unidentified aircraft. The pilot would stare into his hood, sweating profusely, watching the green blip merge with his own.

He had to close to within 200 yards, point blank range in total darkness. The fear of mid-air collision was constant. If the radar lied or if the pilot misjudged the closure rate by 10 knots, he wouldn’t shoot the enemy, he would ram them. They called it painting the target. The pilot had to sneak up behind the Japanese bomber, matching its speed perfectly, invisible in the exhaust wash.

The first kills didn’t look like heroism, they looked like executions. A Corsair pilot, Lieutenant Cecile Swed Albbright, caught a Japanese float plane off the Gilbert Islands. He stalked it for 20 m. The Japanese pilot was flying straight and level, fat and happy, convinced the knight protected him. Albbright closed to 100 yards.

He could see the exhaust flames from the enemy engine. He didn’t just pull the trigger. He verified the silhouette against the stars, ensuring it wasn’t a friendly. Then he unleashed the power of the Corsair’s remaining 50 caliber machine guns. The effect was instantaneous. The incendiary rounds walked through the Japanese fuselage like a chainsaw through balsa wood.

The enemy plane didn’t just crash. It disintegrated. A fireball erupted in the darkness. A sudden, violent sun that illuminated the ocean for miles. Down on the ships, the sailors stopped breathing. They saw the flash. They waited for the sound. Then came the radio call. Cool and detached. Splash. One Betty.

The realization rippled through the fleet. The night corsairs weren’t a science experiment anymore. They were the only thing standing between the sailors and a torpedo in the gut. But the Japanese were not stupid. They were veterans. They realized that the Americans had found a way to see in the dark. They stopped flying single lazy harassment missions.

They began to mass their forces. Intelligence reports started trickling in about a new tactic. The Japanese were gathering their best night flyers, the elite torpedo squadrons, for a coordinated massive duskadon assault. They were going to overwhelm the few ghost corsairs with sheer numbers. Hmer read the reports in the briefing room of the Enterprise.

He looked at his small band of exhausted pilots. They were flying planes held together by wire, landing on a pitching deck that terrified them, hunting an enemy that outnumbered them 10 to one. The skepticism from the admirals had faded, replaced by a desperate, crushing demand for protection. The fleet was heading toward the truck lagoon, the Gibralar of the Pacific, and they were sailing straight into a trap.

Hmer didn’t make a speech. He didn’t quote Shakespeare. He just pointed at the map and told his men to check their vacuum tubes. The expert doubt was gone, replaced by the cold reality that they were about to be tested against the finest aviators the Empire of Japan had left. The haunting period was over. The hunting was about to begin.

The sun dipped below the horizon on February 16th, 1944, and the Pacific Ocean turned into an abyss. This was Operation Hailstone, the massive navy strike against Truck Lagoon, the fortress the Japanese called the Gibralar of the Pacific. For 2 years, this lagoon had been the untouchable sanctuary of the Imperial Fleet.

But now, the American carriers were at the doorstep. As the light faded, the mood on the ships shifted from aggression to anxiety. Every sailor knew the pattern. During the day, the Americans owned the sky, but at night, the Empire struck back. Radar operators on the USS Enterprise watched their screens fill with a terrifying sight.

A massive formation of Japanese torpedo bombers, Kates and Bettis, was lifting off from the island airfields. These weren’t nervous rookies. These were the night trade specialists, the veterans who had terrorized the fleet for 20 months. They were coming to skim the waves at 200 mph and put a torpedo into the side of a carrier.

On the flight deck of the Enterprise, the engine of Chick Hmer’s Corsair spat blue flame into the darkness. The noise was a physical assault. The massive Pratt and Whitney engine was vibrating so hard it blurred the instrument panel. Hmer looked to his right. He couldn’t see his wingman, only the faint blue glow of formation lights.

He was sitting on top of 2,000 gallons of high octane aviation fuel and belts of 50 caliber ammunition about to launch into a black void. The catapult officer swirled a lighted wand. Hmer jammed the throttle forward. The double Wasp engine screamed. Torque trying to twist the plane into the deck. The catapult fired.

The GeForce slammed Hmer into his seat, crushing the air out of his lungs. In 2 seconds, he went from 0 to 150 mph. Then the deck disappeared. He was airborne and he was blind. The transition was instant and disorienting. One second there were deck lights, the next there was absolutely nothing.

No horizon, no stars, just the infinite black of the ocean meeting the sky. His inner ear screamed that he was tumbling backward, a biological illusion that had killed hundreds of pilots. Hmer ignored his body and locked his eyes on the artificial horizon and the gyroscope. He forced his hands to fly the math, not the feeling.

He retracted the gear, feeling the heavy clunk as the wheels folded into the gull wings. The drag from the radar pod on the right wing instantly bit into the airflow, pulling the nose to starboard. He fed in left rudder, establishing the delicate, exhausted equilibrium that was his life now. He climbed to 5,000 ft, swallowed by the cloud layer, and turned on the scope.

Inside the cockpit, the world shrank to a 3-in circle of green phosphoresence. The radar hummed, a high-pitched wine that drilled into his skull. He buried his face in the rubber hood. The sweep line rotated like a clock hand painting the world in strokes of light. Nothing. Nothing. Then a smudge, a bogey. It was a faint trembling blob of light at the 12:00 position 6 miles out.

Hmer keyed his mic. He didn’t shout. His voice was flat mechanical. He called the contact to the ship. The fighter director officer on the Enterprise confirmed it. This was a hostile. Hmer pushed the throttle. The Corsair surged. The chase was on. This wasn’t a dog fight. It was a mathematical stalk. He had to close the distance at a specific rate.

If he came in too fast, he would overshoot and fly right past them. If he came in too slow, they would hear him. He watched the blob grow. It split into two distinct blips. Then three, it was a formation. The Japanese pilots were flying in a tight V, completely unaware that a predator was closing in from behind.

They were cruising comfortably, relying on the darkness that had protected them for years. They thought they were ghosts. They didn’t know there was a ghost hunter on their tail. The range dropped 2 m 1 mile. The radar blips were now burning bright green, dominating the scope. The main bang of the radar pulse began to obscure the return.

Hmer was entering the blind zone. This was the moment of truth. He had to lift his head from the hood and transition from instrument flight to visual kill. In a heartbeat, he looked up. At first, he saw nothing. His eyes strained against the blackness. Then he saw it. Blue exhaust flames. two faint flickering candles in the sky.

It was a Betty bomber flanked by two Kate torpedo planes. They were heavy with explosives, plotting toward the American fleet like flying tankers. Hmer checked his gun switches. He didn’t want to just damage them. He wanted to erase them. He lined up his nose on the trailing Kate. The asymmetrical drag of the radar pod made fine aiming a wrestling match.

He had to kick the rudder pedal hard to keep the pip steady. He was 200 yd away, 150. He could see the outline of the Japanese tail gunner’s canopy. The gunner wasn’t looking at him. He was looking down at the water. Hmer squeezed the trigger. The Corsair shuddered as 350 caliber machine guns erupted.

The sound was a jackhammer tearing through sheet metal. Tracers, streams of red fire walked across the dark sky like a laser beam. They didn’t miss. They slammed into the wing route of the Japanese torpedo bomber. The effect was catastrophic. The Japanese planes were known for their lack of armor and self-sealing fuel tanks. They were flying Zippo lighters.

The incendiary rounds ignited the fuel instantly. The Kate didn’t just catch fire. It turned into a supernova. A ball of orange flame illuminated the entire cloud layer. The Japanese plane pitched up violently, shedding a wing and tumbled toward the ocean, a burning meteor screaming down to the water. Hmer didn’t celebrate.

He hauled back on the stick, pulling up and to the left to avoid the debris field. The element of surprise was gone, or so the Japanese thought. The remaining bombers broke formation, scattering into the dark. They assumed they had been hit by lucky anti-aircraft fire from below. They didn’t realize the fire had come from behind.

They began to weave, banking left and right, trying to throw off the aim of the surface gunners they imagined were down there. It was a fatal mistake. By weaving, they bled off speed. And by staying in the area, they remained on Hmer’s scope. He dove back into the hood. The green worms were wiggling across the screen.

He selected the next target, a Betty Bomber, the leader. It was trying to dive toward the deck, hoping to lose itself in the ground clutter of the waves. Hmer followed. The altimeter unwound frantically. 4,000 ft. 2,000 1,000. The air grew thicker. The humidity rose. Hmer’s eyes burned from the sweat dripping into them. He was flying a 400 mph fighter at night, staring at a TV screen, diving toward the ocean.

It was insanity, but the blip was steady. He leveled off at 500 ft. The salt spray was hitting his windshield. The bomber was right ahead of him. He could see the silhouette against the faint starlight reflecting off the water. This time, the Japanese tail gunner saw him. A stream of inaccurate, panicked return fire sparkled in the dark. It was too late.

Hmer walked his rudder pedals, sliding the Corsair sideways and opened fire. The rounds sawed through the bomber’s fuselage. The Betty shuddered. The starboard engine exploded, vomiting parts and oil into the slipstream. The bomber rolled inverted. It hit the water at 200 mph. There was no explosion, just a massive white geyser that vanished instantly into the wake.

Hmer was now an ace in his own mind. But the night wasn’t over. The sky was full of targets. Other night corsaires from his squadron were joining the slaughter. The radio was a chaotic symphony of callouts. Taliho, Splash One, Fox 2. The Japanese attack force which had launched with the arrogance of conquerors was being dismantled.

They couldn’t form up because they couldn’t see each other. They couldn’t fight back because they couldn’t see the enemy. Every time they tried to steady up for a torpedo run, tracers erupted from the empty darkness and tore them apart. It was psychological torture. The Japanese pilots began to jettison their torpedoes harmlessly into the sea, desperate to gain speed and run for home.

Hmer spotted a fighter, a Zero or an Oscar, trying to escort the retreating bombers. This was the ultimate test. Fighter versus fighter at night. The Japanese pilot was good. He was jinking, changing altitude, sensing he was being hunted. Hmer couldn’t get a lock. The radar blip smeared every time the Japanese pilot turned. Hmer anticipated the move.

He knew the Japanese doctrine. Turn tight. Use the maneuverability. Hmer didn’t turn. He used the Corsair’s brute power. He pulled up into a vertical climb, trading speed for altitude, disappearing into the black roof of the sky. He watched the radar. The Japanese pilot leveled out, thinking he had shaken the tail.

Hmer rolled the Corsair over the top of the loop. He was now diving straight down, invisible, a hammer falling from space. The speed built up, 300, 350, 400. The controls stiffened like concrete. He eased the nose up, lining up the deflection shot. The Japanese fighter passed beneath him. Harmer fired a short controlled burst. He didn’t even need the tracers.

He saw the pieces fly off the enemy canopy. The Japanese fighter nosed over and flew straight into the ocean without ever knowing what killed him. For 4 hours, the slaughter continued. The ghost corsairs rotated back to the carrier, slammed onto the deck, refueled, rearmed, and launched again. The deck crews moved like a pit crew at the Indy500.

Their movements choreographed in red light. They loaded belt after belt of ammunition. They wiped the oil off the windscreens. They patted the pilots on the shoulder, a silent gesture of awe. These men were coming back with empty guns and soot stained faces, shaking from the adrenaline dump, only to go back out into the void. By 3:00 a.m.

, the radar screens on the Enterprise were clear. The massive Japanese strike force had ceased to exist. They hadn’t just been defeated. They had been erased. The few survivors limped back to truck, spreading stories of American demons that could see through clouds and strike without warning. The ocean was littered with burning pools of gasoline and floating aluminum graves.

The night Corsaires circled the fleet one last time, their engines droning a low, victorious growl. Below them, the thousands of sailors on the destroyers and cruisers and carriers slept soundly. They had no idea that 5,000 ft above their heads, a handful of men looking into rubber hoods had just fought one of the most decisive battles of the war.

The era of the washing machine Charlie was dead. The Americans own the night. The dawn overtuck lagoon on February 17th, 1944 brought a light that revealed the true scale of the carnage. As the sun crested the horizon, the sailors of Task Force 58 looked out over a sea that was no longer empty. It was stained with the iridescent sheen of oil and dotted with the jagged floating remains of the Imperial Japanese Navy’s pride.

For the first time in the war, the American fleet felt a strange quiet sense of invulnerability. They had spent the night in the heart of enemy territory. Yet not a single torpedo had found its mark. The ghost corsairs of VFN one zir when were circling for their final landings. Their long soot blackened noses pointed toward the deck of the USS Enterprise.

The Enen Eliminator, once mocked as a suicide sled, had just completed a mission that rewrote the rules of engagement. Chick Hmer brought his aircraft down onto the pitching steel, the hook, grabbing the wire with a violent, familiar jerk. When he climbed out of the cockpit, he didn’t look like a hero.

He looked like a man who had been dragged through a coal mine. His flight suit was soaked in sweat, and his eyes were bloodshot from hours of staring into the green emerald glow of the radar scope. The ground crews swarmed the aircraft, but this time there was no laughter. They looked at the empty ammunition shoots and the scorched barrels of the 50 caliber guns.

They looked at the radar pod, still hummed with heat, its vacuum tubes miraculously intact despite the G-forces of combat. The news of the night’s tally began to filter through the ship’s island. 12 confirmed kills, 19 probables. An entire elite Japanese squadron specialized in night attacks had been systematically dismantled by a handful of pilots flying by math and instinct.

The sun setters, the day fighter pilots, who had spent months calling the night flyers cave dwellers, stood in silence as the night crews walked toward the ready room. The culture of the Navy changed in those 4 hours. The skepticism of the admirals evaporated like mist in the morning sun. They realized that Hmer hadn’t just survived.

He had dominated a domain that the human race had been terrified of since the beginning of time. Intelligence officers soon began to piece together the impact from the other side. Radio intercepts and captured documents revealed a state of absolute panic within the Japanese command. Their pilots, some of the most decorated aces in the Pacific, had returned to base, if they returned at all, claiming they were being hunted by demons.

They described American planes that could see through clouds, planes that didn’t need search lights and pilots who struck with sniper-like precision in total darkness. The psychological shield of the night, which had been Japan’s greatest tactical advantage since the Battle of Seo Island, was shattered. The Japanese high command, issued a desperate new directive.

Avoid direct stern approaches against American formations at night. They recommended high angle diving attacks, but their pilots lacked the training and the radar to execute them. The hunter had become the hunted, and the fear of the ghost Corsair began to spread through the Japanese airfields like a virus. The success of the Donovan doctrine in the European theater was being mirrored here by Hmer’s aggressive radar tactics.

Just as the bomber gunners over Germany had learned that aggression was the only path to survival, the night fighters of the Pacific proved that the best defense was a terrifying proactive offense. Hmer spent the following weeks codified what he had learned. He didn’t talk about the kills. He talked about the initiative. He taught his pilots that the radar wasn’t just a tool for finding the enemy.

It was a tool for seizing the timing of the fight. He emphasized that the first burst of fire in the dark didn’t just need to hit metal. It needed to destroy the enemy pilot’s will to fight. He proved that a single Corsair appearing out of the void could force a dozen bombers to jettison their payloads and flee in terror. As the war progressed toward the Philippines and eventually the Japanese home islands, the ghost corsairs became a permanent fixture of the carrier air groups.

The technology evolved rapidly. The fragile glass vacuum tubes were replaced by more rugged components. The radar pods became smaller and more aerodynamic. The pilots became more proficient, developing a six sense for the green ghosts on their screens. By the time the war reached its bloody climax at Okinawa, the Navy had fully embraced the era of electronic warfare.

The idea of a fleet being blind at night was now a memory of a more primitive age. Every major carrier now boasted a detachment of night fighters, and no Japanese pilot felt safe under the cover of darkness. But for Chick Hour and the pioneers of VFN 101, the end of the war brought a quiet exit. Unlike the flamboyant day aces who returned home to parades and movie contracts, the night fighters remained in the shadows.

Their work had been too secret, too technical, and too lonely for the public to easily grasp. Hmer didn’t seek the spotlight. He had done what needed doing, much like the gunners who had rewritten the manual of air combat over the skies of Europe. He returned to a world that was moving on, a world of jet engines and computers that his own desperate experiments had helped create.

He lived a life of quiet dignity, rarely speaking of the nights he spent buried in a rubber hood, wrestling a lopsided fighter through a black abyss. The statistics eventually told the story that the headlines missed. Analysis of carrier operations in the final year of the war showed a 63% drop in successful Japanese night attacks compared to the early years of the conflict.

While better escorts and proximity fuses played a role, nearly a third of that decline was attributed specifically to the aggressive presence of the night fighter detachments. They had saved thousands of lives and hundreds of ships. Not by being lucky, but by being brave enough to trust a flickering green dot over their own eyes.

They had taken the suicide sled and turned it into the most feared sentry in the Pacific. Richard Chickmer passed away long after the world had forgotten the drone of the double wasp engine. Like so many of his generation, he didn’t view himself as a visionary. He viewed himself as a mechanic of war who found a solution to a lethal problem.

But his legacy is etched into every radar screen on every modern fighter jet flying today. He was the man who taught the Navy that the night belongs to those who are willing to hunt in it. He proved that survival doesn’t come from hiding in the dark, but from making your enemy too scared to enter it. We rescue these stories to ensure that the name of Chick Hmer and the ghost corsairs of the Pacific do not disappear into silence.

They were the ones who saw what no one else could.