On the morning of February 27th, 1945 at 08:30, Private Wilson Douglas Watson crouched behind a jagged ridge on Euoima, watching Japanese soldiers move through trenches 60 yards below him. At 23 years old, he was an Arkansas farm kid with 7 years of schooling carrying a 19lb Browning automatic rifle that his platoon had been pinned down trying to reach for two brutal days.

His commanding officers had told him the hill was impossible. 77 pill boxes in just their battalion sector with reverse slope machine guns and knee mortars that had already killed 14 Marines from his company in the past 72 hours. The Japanese had spent 8 months digging 16 km of interconnected tunnels and caves designed by Lieutenant General Tatamichi Kuribayashi to turn every ridge into a killing ground where American industrial firepower would mean nothing.

Watson’s platoon had been stopped cold at the base of this nameless hill along with the rest of the Third Marine Division’s grinding advance toward airfield number two. Artillery couldn’t touch the reverse slope. Tanks were getting knocked out faster than they could be replaced. Naval gunfire was hitting empty ground while the real enemy positions stayed hidden behind the crest.

When Watson’s squad leader was hit by mortar fragments that morning, the survivors hugged the volcanic ash and waited for someone else to figure out how to move forward. The book said, “You called for more support, more guns, more time.” Watson looked at his bar, 20 rounds in the magazine, 500 rounds per minute, cyclic rate, effective to 600 yards, and decided the book was wrong.

He told his assistant gunner they were going up the hill alone under fire to find out what 60 Japanese soldiers with grenades and mortars would do when one Marine refused to stay pinned down. By the time his ammunition ran out 15 minutes later, the answer was lying all over the reverse slope. The records would later show that one Marine killed 60 men in 15 minutes.

But on the morning of February 27th, 1945, the men of Company G had no idea they were about to witness anything extraordinary. They knew only that their advance had stalled again, pinned at the base of another nameless ridge in the volcanic wasteland that was Eoima. Private Wilson Douglas Watson lay pressed against the black sand, his browning automatic rifle heavy across his forearms, watching mortar rounds explode in methodical patterns across the approaches to Hill 362 Bravo.

The Third Marine Division had been grinding forward for 8 days since the landing, paying for every hundred yards with blood. Major General Graves Erskin’s plan looked clean on paper. cross airfield number two, seized the high ground, pushed toward the unfinished airfield number three. But Lieutenant General Tatamichi Kuribayashi had spent eight months turning that high ground into an interlocking maze of death.

16 km of tunnels connected caves and pill boxes that could survive battleship bombardments, then emerged to rake any Marines foolish enough to silhouette themselves against the sky. Watson had seen the system work with brutal efficiency. On February 25th, the day his battalion first attacked across the southern edge of airfield number two, they had called down 1,200 artillery rounds in a single preparation.

A battleship, two cruisers, and every available gun had hammered the rgeline until the volcanic rock seemed to smoke. Then 26 tanks from companies A and B of the third tank battalion had rolled forward with second battalion 9th Marines, their treads chewing through the ash as machine guns opened from positions that should have been obliterated.

Nine tanks were knocked out in 5 hours. The infantry gained 100 yards. That was the reality Watson faced now, crouched behind cover that offered no real protection from the reverse slope mortars. His squad had been reduced to seven men after Corporal Davis took shrapnel in the neck the previous afternoon. The Japanese had perfected their technique.

Machine guns positioned just behind the military crest, mortars and grenade dischargers on the back slope where American artillery could not reach them. When Marines appeared on the skyline, they died. When Marines stayed in the low ground, they accomplished nothing. The hill rising before Watson’s position measured perhaps 200 yards from base to crest.

Its eastern face scarred by shell holes and littered with the twisted metal of destroyed equipment. Intelligence estimated 77 major fortified positions in just their battalion sector, a density that meant encountering a pillbox or cave every 20 to 30 yards along the front. Each position was designed to support the others, creating overlapping fields of fire that turned any advance into a careful negotiation with death.

Watson understood the tactical problem better than most. The son of Alabama sharecroppers, he had learned to hunt before he could properly read, developing an instinctive grasp of terrain and sightelines that formal military training had only refined. On Bugganville and Guam, he had earned a reputation as a bar gunner who could find the critical moment in a firefight.

The instant when aggressive fire could break enemy resistance or pin them long enough for riflemen to close distance. But this was different. The Japanese positions were too wellsighted, too deeply buried, too professionally constructed to yield to conventional small unit tactics. His weapon reflected both the promise and limitations of American industrial power.

The M1918 2 Browning automatic rifle weighed 19 lbs unloaded, fed from 20 round magazines and could fire at rates between 500 and 650 rounds per minute when set to full. Automatic in the hands of a competent gunner, it provided a rifle squad with the suppressive fire traditionally delivered by crew served machine guns concentrated in a weapon light enough for one man to carry and deploy rapidly.

The effective range extended to 600 yardds for point targets. Though Watson knew that in the broken terrain of Euoima, most engagements would occur at distances measured in tens rather than hundreds of yards. The problem was ammunition. Even carrying 12 magazines, 240 rounds, a bar gunner operating at normal combat rates could exhaust his load in 3 to four minutes of sustained fire.

Watson’s assistant gunner carried additional magazines, as did the riflemen in his squad, but resupply under fire remained a constant concern. The Japanese understood this limitation and had structured their defenses to exploit it, using disciplined fire to force American automatic weapons to reveal their positions, then concentrating mortars and grenades on those locations until the gunners were forced to displace or die.

At 08:30, Watson watched his platoon leader, Second Lieutenant Morrison, crawl forward to study the ridge through binoculars. The morning bombardment had concluded 20 minutes earlier. 600 rounds of core artillery followed by naval gunfire from destroyers positioned offshore. Smoke still drifted from the crest, but Watson could see movement in the trenches that connected the reverse slope positions.

The Japanese had weathered another preparation and were adjusting their weapons to meet the inevitable infantry assault. Morrison slid back to the command group, his face grim. Same story, he told the squad leaders. Mortars behind the hill, machine guns in the caves. We go up that slope. We’re going to lose half the platoon before we reach the top.

He paused, studying the terrain with the careful attention of an officer who had already buried too many Marines. Battalion wants us to try the left shoulder, see if we can get around the main positions. Watson knew that flanking movement would fail. The Japanese had spent months studying every approach, registering their mortars on every piece of dead ground that might offer concealment.

Moving left would only expose the platoon to additional fields of fire without eliminating the positions that commanded their current location. The solution, if one existed, lay straight ahead, up the hill, through the killing ground, into direct confrontation with an enemy who had every advantage except numbers.

As Morrison began positioning his men for the flanking attempt, Watson made his decision. The official records would describe his actions in the passive voice of military citations. Boldly rushed, dauntlessly scaled, fought furiously. But the reality was simpler and more personal. He had carried the bar through two previous campaigns, had learned to trust its devastating firepower at close range, and had seen what happened to units that allowed themselves to be pinned down by inferior numbers in superior positions.

Someone had to move forward, and institutional caution was killing more Marines than individual courage. The pillbox that stopped Watson’s advance on February 26th had been constructed with the methodical precision that characterized Japanese defensive engineering throughout the Pacific War.

Built into a natural depression in the volcanic rock, its concrete walls were 3 ft thick, reinforced with steel rails salvaged from the island’s narrow gauge mining railway. The firing embraasure measured 18 in wide by 6 in high, just large enough for the muzzle of a type 92 heavy machine gun to traverse across the approaches while remaining virtually immune to direct fire from rifles and light weapons.

Inside, three Japanese soldiers maintained a weapon that could deliver 7.7 mm rounds at 550 rounds per minute out to effective ranges exceeding 800 yd. The Type 92 represented the culmination of Japanese machine gun development, a water cooled design that could sustain prolonged fire without the barrel changes required by air cooled weapons.

Its crew had registered their fields of fire during the weeks of preparation, marking range cards with precise distances to rocks, shell craters, and other terrain features that attacking Marines might use for cover. Watson’s squad encountered this position at 0915, advancing in the standard formation that had proven effective on Bugganville and Guam.

The point man moved 15 yards ahead of the main body with Watson and his assistant bar gunner positioned to provide immediate suppressive fire if the squad came under attack. Behind them, six riflemen carried M1 Garands loaded with eight round clips of 306 ammunition. Each man also bearing two fragmentation grenades and a bayonet for close combat.

The machine gun opened fire when the point man was 30 yards from the embraasure. Its first burst catching Private Jenkins in the chest and spinning him into a shell crater where he lay motionless. The remaining Marines dove for cover as bullets cracked overhead, seeking protection behind rocks and debris that provided concealment but little actual ballistic protection.

Watson rolled behind a twisted piece of aircraft wreckage. probably from one of the Japanese fighters destroyed during the preliminary bombardment and tried to identify the source of the fire. The muzzle flash was nearly invisible in the shadow of the embraasure, but Watson could track the gun’s location by following the trajectory of tracers as they burned out downrange.

Every fifth round in the Japanese ammunition belt contained a phosphorous element that left a bright streak, allowing the gunner to observe the fall of his shots and adjust [clears throat] fire accordingly. Watson counted the intervals between bursts, noting that the crew was firing in six to eight round sequences with brief pauses to allow the barrel to cool and to shift their aim to different targets.

His squad leader, Sergeant Martinez, had taken cover behind a boulder 20 yards to Watson’s left. Using hand signals, Martinez indicated that he wanted the bar to suppress the machine gun position while riflemen attempted to work around the flanks. Watson nodded understanding, then checked his weapon and ammunition load.

He carried 12 20 round magazines in a canvas bandelier with four additional magazines distributed among his assistant and the nearest riflemen. At sustained rates of fire, this represented perhaps 3 minutes of continuous combat before resupply became critical. The tactical problem was identical to dozens Watson had encountered during previous campaigns, but the terrain made conventional solutions nearly impossible.

The pillbox commanded open ground extending 50 yards in every direction with no dead space where Marines could approach unobserved. The reverse slope behind the position almost certainly contained supporting weapons, mortars, or grenade dischargers that could drop rounds on any Marines who managed to flank the main gun.

Previous assaults in this sector had foundered when riflemen attempting to bypass strongly held positions found themselves caught in crossfire from mutually supporting bunkers. Watson understood that suppressive fire alone would not solve the problem. The concrete walls were thick enough to stop rifle bullets, and the embraasure was too narrow to allow effective fire from his current position.

He needed to close distance, bringing his bar within effective range of the firing slit while somehow avoiding the machine gun that was specifically positioned to prevent exactly that approach. The solution required speed, aggression, and precise timing, qualities that military doctrine discouraged in favor of methodical advances supported by overwhelming firepower.

At 0925, Watson made his decision. Rising from behind the aircraft wreckage, he sprinted directly toward the pillbox, his bar held ready at waist level. The Japanese machine gunner, startled by the sudden movement, swung his weapon to engage this new threat, but Watson had already covered half the distance before the first rounds passed over his head.

At 15 yards, close enough to see the dark outline of the embraasure, Watson opened fire. The bar’s 20 round magazine emptied in 4 seconds of sustained automatic fire. 30 ought six rounds punching through the narrow opening and ricocheting off the interior walls in a cone of lethal fragments. Watson dropped the empty magazine, inserted a fresh one, and continued his charge, firing short bursts as he closed the final yards to the position.

The Japanese machine gun fell silent, its crew either killed or forced to take cover from the storm of steel filling their confined space. Reaching the rear entrance of the pillbox, Watson found two Japanese soldiers attempting to escape through a communication trench that connected their position to other bunkers farther up the slope.

Both men carried Arisaka rifles and appeared stunned by the sudden [clears throat] collapse of their carefully prepared defense. Watson killed them with a burst from his bar, then threw a fragmentation grenade into the pillbox to ensure the machine gun crew could not resume firing. The explosion shattered the concrete ceiling and collapsed part of the rear wall, rendering the position unusable.

Watson’s assistant gunner, Private Cooper, reached the pillbox 30 seconds later, followed by the rest of the squad. Sergeant Martinez conducted a quick search of the interior, confirming three Japanese dead and recovering the Type 92 machine gun, its barrel shattered by fragments from Watson’s rifle fire.

The immediate tactical problem was solved, but Watson realized that his aggressive assault had attracted attention from other positions on the ridge. Mortar rounds began falling around the captured pillbox, forcing the squad to evacuate the area before Japanese artillery could register their location. As they withdrew to covered positions, Watson noted movement in the trenches above them.

More Japanese soldiers adjusting their defenses to meet the American advance. The pillbox assault had demonstrated both the potential and limitations of individual initiative in modern warfare. Watson’s charge had eliminated a position that conventional tactics could not crack, allowing his platoon to advance beyond the point where they had been pinned for 2 days.

But the success was local and temporary, dependent on surprise and exceptional marksmanship that could not be routinely replicated across an entire battalion front. The ridge still bristled with defensive positions, each requiring similar acts of tactical improvisation to overcome. As his squad reorganized for the next phase of the attack, Watson checked his remaining ammunition and considered the terrain ahead.

The captured pillbox represented one small victory in a campaign that would ultimately require hundreds of similar actions, each carried out by Marines who understood that institutional doctrine, however sound in principle, sometimes yielded to individual judgment under fire. The morning of February 27th opened with a 45minute artillery preparation that shook the volcanic island from its beaches to its central plateau.

600 rounds of core artillery crashed into the high ground north of airfield number two, followed by naval gunfire from destroyers positioned 3 mi offshore. Watson crouched in a shell crater with his assistant gunner, feeling the concussions through the soles of his boots as 155 mm howitzer shells detonated against the ridge line where his battalion would advance within the hour.

At 0800, Colonel Howard Kenyon’s 9inth Marines resumed their attack with First Battalion on the right, second battalion on the left, and third battalion in reserve. 11 tanks from the third tank battalion moved forward to support second battalion’s advance. Their 75 mm guns, seeking targets among the cave mouths and reinforced positions that had survived the bombardment.

Within 90 minutes, Japanese anti-tank fire had knocked out nine of the 11 Shermans, leaving them burning hulks scattered across the approaches to Hill 362 Bravo. Watson’s platoon advanced with Company G in the left sector, following a compass bearing that led directly toward the most heavily fortified section of Kuribayashi’s main defensive belt.

Intelligence estimates placed the enemy strength at roughly 2100 effectives in this sector, supported by mortars ranging from 50mm knee mortars to 90 millimeter battalion guns positioned in caves that connected through the tunnel system. Each defensive position had been surveyed and registered during months of preparation, creating interlocking fields of fire that channeled attacking forces into predetermined killing zones.

The terrain itself seemed designed to favor the defense. The ground rose in a series of terraces carved from volcanic rock. Each level offering natural firing positions that overlooked the approaches below. Ravines and draws provided concealed routes for Japanese reinforcements while exposing American flanking movements to observation and fire.

The volcanic ash that covered much of the island created dust clouds whenever artillery struck, but also deadened the sound of movement and made it difficult for attacking forces to coordinate their actions. By 10:30, Watson’s company had advanced 150 yards beyond their morning jumpoff line. A gain purchased with eight casualties, including their company commander, who took mortar fragments in both legs while directing the assault on a fortified cave complex.

The advance stalled when the lead platoon encountered a reverse slope position that dominated the next objective, a rocky outcrop designated Hill Peter on the tactical maps. Watson could see the problem clearly from his position in a communication trench abandoned by retreating Japanese. Hill Peter rose 60 ft above the surrounding terrain, its military crest honeycombed with firing positions that commanded every possible approach.

Mortar fire from the reverse slope had already wounded three Marines who attempted to cross the open ground, and machine gun tracers from positions Watson could not locate were forcing his platoon to remain in whatever cover they could find. Second Lieutenant Morrison, who had assumed command after Captain Bradley’s evacuation, studied the hill through field glasses while Japanese rounds cracked overhead.

The standard solution called for artillery support, but the forward observers were reporting difficulty in adjusting fire onto reverse slope targets. Naval gunfire could reach the general area, but the caves, and bunkers were too small and too well protected for effective engagement by ship-based weapons. At 11:15, Morrison made the decision to assault Hill Peter with rifle platoon supported by whatever fire the company could mass from its current positions.

Watson’s squad received orders to advance on the left flank using a shallow ravine for concealment until they reached the base of the hill. From there, they would assault straight up the slope while other elements provided covering fire. Watson understood immediately that the plan would fail. The ravine offered concealment from direct fire weapons, but Japanese mortars had almost certainly registered the route during their defensive preparations.

Any force large enough to assault the hill would be detected and engaged while still hundreds of yards from the objective. The reverse slope positions would remain untouched by American supporting fires, allowing enemy machine guns to engage the assault force as it crested the hill. As his squad prepared to move out, Watson noticed that his assistant bar gunner, Private Cooper, was running a fever and could barely hold his rifle steady.

The youngster had been fighting dysentery for 3 days, but had refused evacuation, unwilling to leave his position during active combat operations. Watson reassigned Cooper to stay with the wounded and selected Private Stevens, a rifleman with experience as an ammunition bearer, to accompany him up the hill.

The approach began at 11:45 with Watson’s squad leading the advance down the ravine while First Squad provided overwatch from positions around the abandoned communication trench. Mortar rounds began falling within minutes, forcing the Marines to bound forward in short rushes between impacts. Watson counted the intervals between rounds, noting that the Japanese mortar crews were firing deliberate aimed shots rather than rapid concentrations, conserving ammunition while maintaining steady pressure on the advancing Americans. At the base of Hill Peter,

Watson’s squad found themselves pinned by machine gun fire from at least three positions on the military crest. The weapons were sighted to create a beaten zone that covered the entire width of the slope, making it impossible for infantry to advance using conventional fire and movement techniques. Stevens was hit in the shoulder during the first exchange of fire, leaving Watson with six effective riflemen and diminishing options for tactical maneuver.

Watson realized that the assault would succeed or fail based on the next few minutes of combat. His bar represented the heaviest firepower available to the attacking force, but its effectiveness depended on his ability to close within effective range of the enemy positions. The machine guns on the crest were positioned to engage targets at ranges where rifle fire would be ineffective, counting on distance and protective cover to negate American small arms fire.

Making his decision, Watson signaled Stevens to follow him and began climbing the rocky slope under direct fire from multiple weapons. Japanese grenades exploded around them as they scrambled over loose volcanic rock. Each step bringing them closer to the reverse slope positions that had dominated this section of the battlefield for 8 days.

Stevens, despite his wounded shoulder, managed to keep pace while carrying additional magazines for Watson’s bar. At 50 yards from the crest, Watson could see Japanese soldiers moving in trenches that connected the various fighting positions. Many appeared to be adjusting their weapons to engage the two Marines who had somehow survived the climb up the exposed slope.

Watson counted at least 15 enemy soldiers visible in the trench system with more movement suggesting additional defenders in covered positions behind the military crest. The final rush to the top of hill, Peter would require Watson to expose himself completely, standing upright in full view of multiple enemy positions while delivering accurate fire at close range.

Success depended on shock, speed, and the devastating firepower of the bar. At distances where every round would find its target, Stevens would provide what support he could with his M1 Garand, but the critical action belonged to Watson and his automatic rifle. Watson reached the crest of Hill Peter at 12:05 on February 27th, emerging from the final yards of his climb to find himself standing alone on a narrow ridge of volcanic rock with Japanese soldiers in trenches on three sides.

The reverse slope dropped away below him in a maze of interconnected fighting positions, each occupied by enemy infantry who had been waiting for exactly this moment. Stevens lay 20 yards down the slope, clutching his wounded shoulder while trying to provide covering fire with his Garand. The Japanese response was immediate and coordinated.

Knee mortars began dropping 50 mm rounds around Watson’s position while riflemen in the trenches opened fire with Type 99 Aerosakas and grenades arked through the air from multiple directions, their fuses timed to explode at head height above the ridge line. Watson had perhaps 30 seconds before the combined fire would force him off the crest or kill him where he stood.

Instead of seeking cover, Watson planted his feet and opened fire with the bar from his hip, sweeping the weapon in controlled bursts across the trench system below. His first magazine caught a cluster of Japanese soldiers attempting to adjust a knee mortar. The 306 rounds tearing through their position and silencing the weapon.

Watson dropped the empty magazine, inserted a fresh one, and continued firing without pause. The tactical situation favored neither side. Watson held the high ground, and possessed superior firepower, but his exposed position made him vulnerable to fire from multiple directions. The Japanese defenders enjoyed cover and concealment in their prepared positions, but they had not anticipated facing automatic weapons fire at such close range.

The battle became a contest of will and ammunition with Watson’s survival depending on his ability to suppress multiple enemy positions faster than they could coordinate their response. A knee mortar round exploded 6 ft from Watson’s position, showering him with volcanic rock and metal fragments that opened cuts across his face and neck.

He staggered but maintained his footing, adjusting his aim toward a machine gun position that had begun firing from a cave mouth on the eastern slope. The bar’s bullets struck the cave entrance, forcing the crew to abandon their weapon and seek deeper cover within the tunnel system. Japanese soldiers in the main trench began throwing grenades and coordinated volleys, attempting to saturate Watson’s position with overlapping explosions.

Most fell short, detonating on the forward slope where they caused no casualties, but several landed close enough to force Watson to shift position along the narrow crest. Each movement exposed him to fire from different directions, requiring split-second decisions about which threats to engage first.

Watson’s fourth magazine ran dry as he engaged a group of riflemen who had emerged from a covered position to his left. Stevens managed to wound one of them with his grand, but the others continued advancing up the slope, apparently convinced that the isolated marine on the crest could be overwhelmed by direct assault. Watson inserted his fifth magazine and cut down three Japanese soldiers at ranges under 20 yards, their bodies tumbling back down the rocky incline.

The intensity of fire from the reverse slope began to diminish as Watson’s sustained automatic fire took effect. Bodies lay scattered throughout the trench system, and the survivors had withdrawn to covered positions where they could no longer effectively engage the marine on the crest. Watson counted approximately 20 enemy dead visible from his position with an unknown number of wounded who had crawled away or been dragged to safety by their comrades.

A mortar round struck the rgeline 10 yards to Watson’s right, the explosion knocking him to his knees and opening a gash along his left arm. Blood ran down his sleeve and made his grip on the bar slippery, but he managed to maintain control of the weapon while scanning for new targets. The Japanese fire was becoming more sporadic, suggesting that their ammunition was running low or that the survivors were conserving rounds for a final desperate engagement.

Watson’s ammunition situation was approaching critical levels. He had fired eight of his 12 magazines and could see no immediate prospect for resupply. Stevens remained pinned on the forward slope, unable to advance with additional ammunition because of sustained fire from positions Watson had not yet located.

The rest of his squad was scattered along the base of the hill, prevented from climbing by. Japanese fire from other sectors of the defensive line. At 1218, Watson [clears throat] detected movement in a communication trench that connected the reverse slope positions to other parts of the Japanese defensive system. A squad of enemy soldiers was attempting to maneuver into position for a flanking attack, using covered roots to approach his position from the blind side of the ridge.

Watson shifted his position to engage this new threat, expending his ninth magazine in a series of precise bursts that caught the Japanese soldiers as they emerged from the trench mouth. The silence that followed was broken only by the distant sound of artillery fire from other sectors of the battlefield. Watson had been standing on the crest for 13 minutes, engaged in continuous combat at ranges that rarely exceeded 50 yards.

His bar had proved its worth as a close assault weapon, delivering devastating firepower that no rifle squad could match, but the cost in ammunition had been enormous. Two magazines remained, representing perhaps 90 seconds of combat at his current rate of expenditure. Japanese voices echoed from the tunnel system below, suggesting that reinforcements were moving through the underground passages to reinforce the reverse slope positions.

Watson realized that his time on the hill was limited not by enemy fire, which had largely ceased, but by his dwindling ammunition supply. When his last rounds were expended, the Japanese would emerge from their covered positions to retake the crest. Stevens finally managed to climb within shouting distance, his wounded shoulder making the ascent difficult, but not impossible.

“How many you got left?” he called, ducking as a sniper’s bullet cracked overhead from a position somewhere on the northern slope. Two magazines, Watson replied, not taking his eyes off the trench system below. Maybe 40 rounds. He had been fighting for almost 15 minutes without pause, longer than any bar gunner could reasonably expect to survive in such an exposed position.

The hill was his, but only as long as he could continue to deny it to the enemy. The sound of American voices carried up from the base of the hill, indicating that the rest of his platoon was finally moving to support his position. Watson estimated another 5 minutes before they could reach the crest, assuming they encountered no serious resistance during their climb, whether his remaining ammunition would last that long depended on how many Japanese soldiers remained alive in the defensive positions below, and how desperately they wanted to

retake the high ground. Watson’s ammunition ran out at 1220. his final magazine emptying into a group of Japanese soldiers who had attempted to rush his position from the communication trench. The sudden silence of his bar marked the end of 15 minutes of sustained combat that had transformed Hill Peter from an impregnable strong point into a field of bodies scattered across the volcanic rock.

Stevens reached the crest 30 seconds later, followed by Sergeant Martinez and the remainder of the squad. their arrival ensuring that the position would remain in American hands. The immediate aftermath revealed the scope of Watson’s achievement. A hasty count identified 63 Japanese dead in the trenches and cave mouths below the ridge line with blood trails indicating additional wounded who had been dragged into the tunnel system.

The reverse slope defenses that had stopped second battalion’s advance for two days had been systematically destroyed by one marine with an automatic rifle, firing from an exposed position that military doctrine considered untenable. Watson himself bore the physical cost of his stand. Seven separate wounds marked his body, ranging from grenade fragments in his face and arms to a deep gash along his left thigh, where a mortar round had detonated close enough to knock him down. His uniform was shredded.

His bar’s bipod had been shot away, and the weapons barrel glowed red from sustained fire that had pushed it beyond normal operational limits. Yet, he remained conscious and alert, directing his squad’s occupation of the captured positions while medics treated his injuries. The tactical consequences extended far beyond Watson’s immediate sector.

With Hill Peter secured, Second Battalion could advance its supporting weapons to positions that commanded the approaches to Hill 3, 62 Bravo. Lieutenant Colonel Robert Kushman ordered his reserve companies forward, exploiting the breakthrough that Watson’s action had created. By 1400 hours, the battalion had advanced 700 yardds beyond its morning positions, the deepest penetration achieved by any unit in the Third Marine Division since the landing.

Colonel Kenyon’s ninth Marines consolidated their gains as Japanese resistance shifted from coordinated defense to individual acts of desperation. Enemy soldiers emerged from caves and tunnels throughout the afternoon. Some attempting to reach American positions with satchel charges, others simply firing until their ammunition was exhausted.

The organized defensive system that Kurabayashi had constructed over eight months was fragmenting under pressure from multiple directions. Though individual strong points continued to exact a terrible price from attacking forces, Watson remained with his squad through the afternoon despite medical recommendations that he be evacuated for treatment of his wounds.

The cuts on his face had stopped bleeding, but the gash in his thigh required constant attention to prevent infection in the volcanic environment of Euoima. He refused morphine, claiming that he needed to remain alert in case of counterattack, though his squadmates noted that his hands shook whenever he tried to reload magazines for his replacement bar.

The Japanese response came at dusk when approximately 40 soldiers emerged from the tunnel system in a coordinated attempt to retake. Hill. Peter. Watson’s squad, now reinforced with machine guns and mortars, repelled the attack without difficulty, killing 23 enemy soldiers while suffering only minor casualties.

The ease of this engagement demonstrated how completely Watson’s afternoon stand had broken the defensive system that had dominated this sector of the battlefield. On March 2nd, during the continued advance toward Hill 362 Bravo, Watson was struck in the neck by mortar fragments while directing fire against a cave complex.

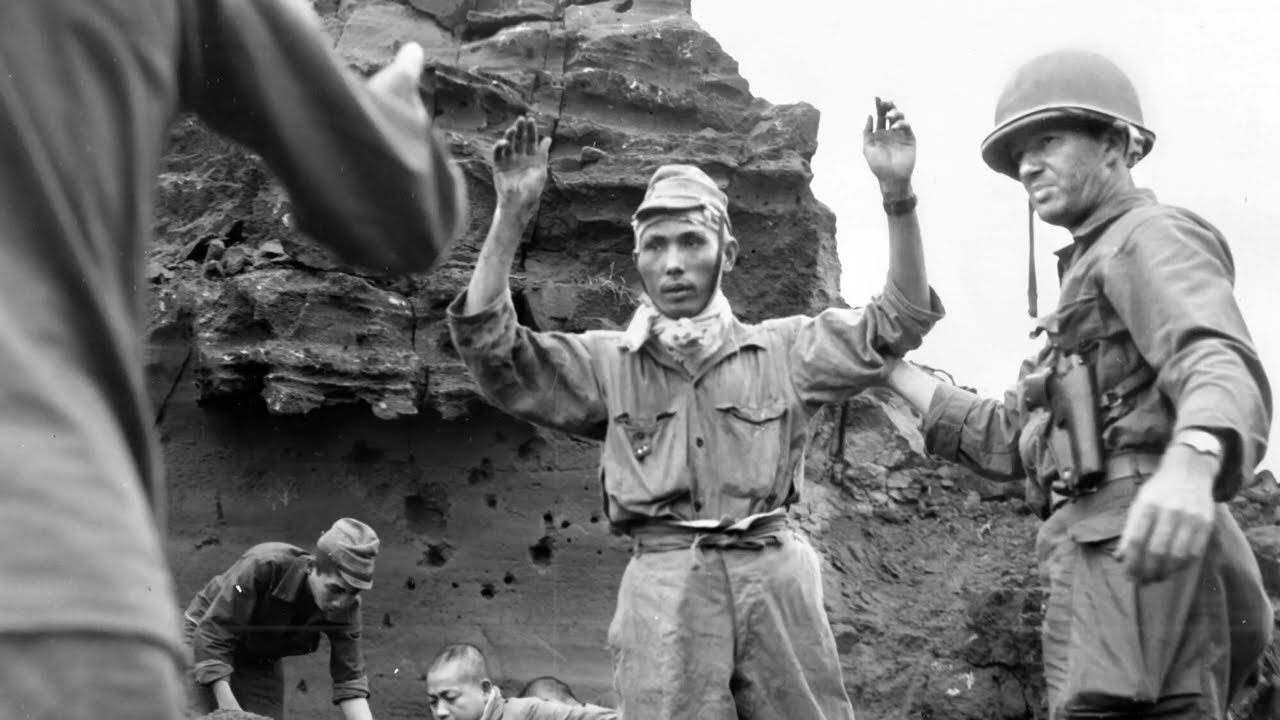

The wound was serious enough to require immediate evacuation, ending his combat service on Euima after 8 days of nearly continuous fighting. His departure marked the conclusion of an individual performance that had fundamentally altered the tactical situation in second battalion sector. The official recognition came months later when President Harry Truman presented Watson with the Medal of Honor at the White House on October 5th, 1945.

The citation described his actions in the passive voice of military bureaucracy, but the essential facts remained unaltered by formal language. One Marine with an automatic rifle had killed approximately 60 enemy soldiers in 15 minutes of exposed combat, breaking a defensive position that had stopped an entire battalion.

Watson’s post-war life reflected the complex reality of heroism in democratic society. After discharge from the Marine Corps, he struggled with civilian employment, eventually enlisting in the Army Air Forces and later transferring to the regular army. His service record showed periodic disciplinary problems, suggesting that the qualities that made him effective in combat did not necessarily translate to peaceime military routine.

He retired as a staff sergeant in 1966, having served in two branches of the armed forces over a career that spanned more than two decades. The broader context of Euoima placed Watson’s achievement in perspective. The island’s conquest required 36 days of combat that cost the lives of 6,800 American servicemen and wounded nearly 19,000 others.

Japanese casualties totaled approximately 21,000 with only a few hundred prisoners taken alive. Watson’s 15 minutes on Hiller represented a tiny fraction of this enormous battle. Yet his action demonstrated how individual initiative could break defensive systems that conventional tactics could not crack. The technical lessons were equally significant.

Watson’s BAR had functioned flawlessly despite being pushed far beyond its normal operational parameters, validating the weapon’s design for sustained automatic fire at close range. His expenditure of 10 20 round magazines in 15 minutes represented a rate of fire that few infantry weapons could match, delivered with accuracy that reflected both superior marksmanship and intimate familiarity with his equipment under combat conditions.

The human cost extended beyond Watson himself to encompass the 63 Japanese soldiers whose bodies lay scattered across Hill Peter’s reverse slope. Each represented a family in the home islands, a community that would receive notification of death in service to the emperor. Their defensive positions had been expertly constructed and courageously defended, but individual skill and determination had overcome institutional advantages in terrain and fortification.

Watson died in Arkansas in 1994, buried in Russell Cemetery with a simple headstone noting his Medal of Honor. Veterans of the 9inth Marines remembered him as the Marine who proved that courage and firepower could overcome any defensive position, no matter how carefully prepared or determinedly held. His legacy remained embedded in the tactical doctrine that emphasized individual initiative and aggressive use of automatic weapons at the squad