47 American paratroopers walked into this jungle. 19 walked out. The rest swallowed by the green, dragged into tunnel networks so deep that recovery teams never found them. And you know what the Pentagon did? They drew a red line on the map and wrote three words. Offlimits Australians only. Wait, Australians? The guys from the country with more kangaroos than soldiers.

Those Australians were allowed to go where United States Marines were forbidden to set foot. Oh, this story gets so much wilder than you think because what those Aussie operators were doing in those mountains, the methods, the tactics, the things they left behind for the Vietkong to find was so effective and so disturbing that American liaison officers were requesting emergency transfers just to get away from them.

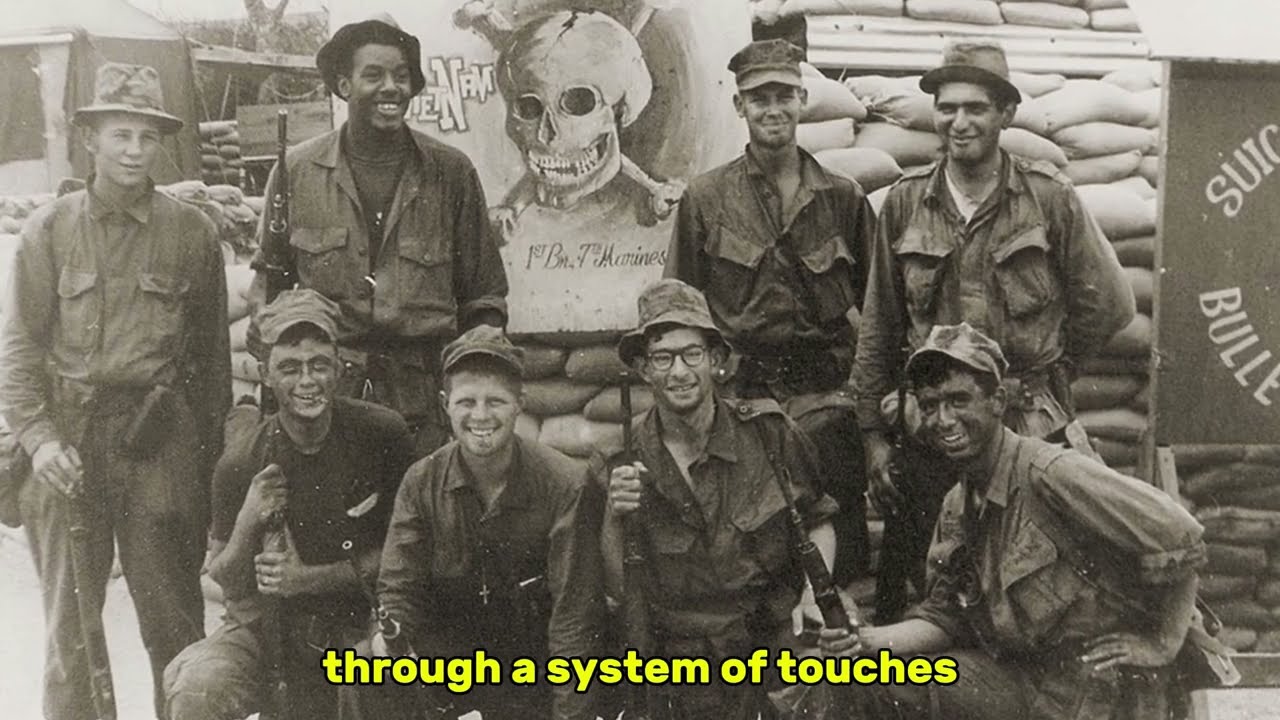

One Marine sergeant came back from a joint patrol and submitted a two-word report that got immediately classified. Those two words, we’re amateurs. You’re about to discover why the most powerful military on Earth handed over 14 square kilometers of Vietnamese jungle to 150 men from a country most Americans couldn’t find on a map.

And trust me, by the end of this video, you’ll understand why the Vietkong stopped calling them soldiers. They called them something else. Maung, the jungle ghosts. Stay with me. 23 km southeast of the Australian base at Nui Dot, the Long High Mountains rose from the coastal plains like the spine of some ancient beast.

From the air, the Massie appeared deceptively small, a mere 14 km of jungle covered limestone extending toward the South China Sea. American aerial reconnaissance had photographed every square meter. B52 bombers had dropped over 40,000 tons of ordinance on its slopes between 1966 and 1968. The third battalion, fifth marines, had conducted three major operations into its northern approaches.

And yet, the Vietkong’s D445 provincial mobile battalion continued to operate from its caves and tunnel complexes with apparent impunity. What the Americans did not understand, what they could not understand through the lens of conventional military doctrine was that the Longhai Mountains were not a position to be taken.

They were a living organism, a network of underground rivers, limestone caverns, and tunnel systems that had been expanded and fortified for over two decades. The Vietkong had not simply dug into these mountains. They had become part of them. But this was only the first layer of a mystery that would consume American military intelligence for the next 3 years.

In March of 1967, a company from the 173rd Airborne Brigade attempted a sweep and clear operation through the Longhai’s eastern approaches. What happened over the following 72 hours would result in the operation being classified at the highest levels of MACV command. 47 American paratroopers entered the jungle. 19 walked out. The rest had not been killed by conventional ambush or booby traps.

They had simply vanished. Their bodies never recovered. Their fates unknown. Their names added to the MIA roles that would haunt American families for decades to come. The official afteraction report. attributed the losses to enemy action and complex terrain. The unofficial assessment circulated only among senior intelligence officers told a different story.

The Vietkong had not fought the Americans. They had hunted [music] them systematically, patiently, one by one, pulling men from their patrol lines without a single shot being fired. This was the moment when MAV command made a decision that would remain buried in classified archives for over 40 years. The Long High Mountains were declared off limits to American ground forces, but the problem remained.

D445 Battalion continued launching attacks on Allied positions, and someone had to deal with them. Enter the Australians. To understand why the Pentagon turned to a force of barely 500 men to accomplish what 20,000 Marines could not, one must first understand the peculiar nature of the Australian military presence in Vietnam.

The first Australian task force had arrived in Fui province [music] in 1966 with a mandate that differed fundamentally from American operational doctrine. While US forces measured success in body counts and territory seized, the Australians had been given a single objective. Pacify Fui province using whatever methods they deemed necessary. The key word was whatever.

Within the Australian Task Force operated a unit so small it barely registered on American organizational charts. The Special Air Service Regiment or SAS, three squadrons rotating through Vietnam, never more than 150 men in country at any given time. Their official designation was [music] reconnaissance.

Their actual function was something far more primal, something that would make American interrogators at the Phoenix program look like amateur enthusiasts. Captain William Billy Dundis had commanded second squadron SAS since February of 1968. A former sheep station manager from rural Queensland, Dundis had never seen combat before, his first tour in Borneo during the Indonesian confrontation of 1965.

What he learned in those Borneo jungles, tracking communist insurgents through terrain so dense that visibility rarely exceeded 3 m would transform him into something the Vietkong had never encountered. But the true revelation came not from Dundis himself, but from the men who served under him and specifically from a group whose very existence the Australian government would deny [music] for decades the Aboriginal trackers of the Australian army.

Private Dorian Walker was a Pentubi man from the Western Desert, recruited into the army through a program that officially did not exist. His people had survived for 40,000 years in one of the most unforgiving environments on Earth by developing sensory capabilities that Western science still struggles to explain. Walker could track a man through jungle so dense that American infrared sensors registered nothing but green blur.

He could determine the age of a footprint to within 6 hours by the moisture content of disturbed vegetation. He could smell a Vietnamese soldiers rice and new mom diet from 400 m downwind. When Walker first arrived at Nui Da in April of 1968, the American liaison officer attached to the Australian task force, a MAC Vsaw captain named James Morrison, dismissed the Tracker program as colonial nostalgia.

Aboriginals tracking humans in Vietnam. The notion seemed absurd. A relic of 19th century frontier warfare transplanted into the age of helicopter gunships and electronic sensors. Morrison would revise this assessment exactly 17 days later under circumstances that would result in his immediate request for transfer back to American command.

But we are getting ahead of ourselves. Before we can [music] understand what Morrison witnessed in those mountains, we must first examine the doctrine that made it possible. [music] The tactical philosophy that separated Australian SAS operations from everything the Americans had attempted. The American approach to counterinsurgency in Vietnam operated on a simple principle.

Find the enemy, fix them in position, and destroy them with overwhelming firepower. This doctrine had won World War II in Korea. It had crushed conventional armies across three continents. But in the triple canopy jungles of Southeast Asia, it had one fatal flaw. You cannot destroy what you cannot see.

The Vietkong understood this intimately. They had studied American tactics for years before the first marine battalions waited ashore at [music] Daang. They knew that Americans moved in large units, made noise, followed predictable patterns, [music] and relied on artillery and air support to compensate for tactical limitations. Against such an enemy, the jungle itself became the ultimate weapon.

All you had to do was wait. Australian SAS doctrine inverted every assumption of American warfare. Where Americans moved in platoon or company strength, Australian patrols consisted of five men. Where Americans cleared jungle with defoliants and napalm, Australians learned to move through it without disturbing a single leaf.

Where Americans announced their presence with helicopter insertions and radio chatter, Australians walked in from kilometers away, established ambush positions, and waited in absolute silence for days at a time. But the most significant difference, the one that would shock and disturb American observers, lay not in tactics, but in psychology.

Australian SAS operators did not see themselves as soldiers conducting counterinsurgency operations. They saw themselves as hunters. And in hunting, there is no such thing as a fair fight. The first documented American observation of Australian SAS methods occurred on the 15th of June 1968 when Captain Morrison accompanied a five-man patrol into the northern approaches of the Longhai Mountains.

Well, what he recorded in his classified afteraction report would eventually reach the desk of MACV commander General Kraton Abrams himself. The patrol had departed Newi Dot at oh 300 hours, moving on foot through 8 km of rubber plantation before reaching the jungle fringe. Morrison noted immediately that the Australians moved differently than any American unit he had served with.

There was no talking, no hand signals, no sound whatsoever. The patrol leader communicated through a system of touches. Shoulder for stop, arm for direction, hand signals so subtle Morrison [music] missed half of them. By dawn, they had covered 12 km and established a position overlooking a trail intersection that intelligence suggested served as a courier route for D445 battalion.

What happened next would form the centerpiece of Morrison’s report. The Australians did not set up a conventional ambush. They did not dig fighting positions or establish fields of fire. Instead, four men melted into the undergrowth on either side of the trail, while the fifth, Private Walker, the Aboriginal Tracker, moved forward to examine the path itself.

For 20 minutes, Walker studied the trail, occasionally lowering his face to within centimeters of the ground, sniffing the air, touching vegetation with his fingertips. When he returned, Walker communicated something to the patrol leader in a whisper so soft Morrison could not hear it despite being less than 2 meters away.

The patrol leader nodded and the Australians began repositioning with movement so slow they seemed almost geological. 11 hours later, a three-man Vietkong courier team walked directly into the ambush position. They never knew the Australians were there. The first indication of danger came when the lead courier stepped on a pressurreleased [music] detonator connected to a claymore mine.

The entire engagement lasted 4 seconds. Three enemy eliminated. Zero Australian casualties. Zero shots fired that could be heard beyond a 50 m radius. But this was not what disturbed Morrison. What disturbed him came after. Standard American doctrine called for immediate extraction following contact with enemy forces. Get in. Hit hard.

get out before reinforcements arrived. The Australians operated under no such constraints. Following the ambush, the patrol remained in position for another 6 hours, watching the trail. At 14:30 hours, a second Vietkong element arrived. A seven-man search team sent to investigate when the couriers failed to report.

They found the bodies of their comrades arranged in a specific pattern that Morrison would later describe as ritualistic. The three dead couriers had been positioned sitting upright against trees, their eyes open, their weapons placed across their laps as if they [music] were resting. A playing card, the Ace of Spades, had been tucked into each man’s collar.

The psychological effect on the search team was immediate and visible. Even from 50 m away, Morrison could see the terror in their movements, the way they clustered together rather than spreading out, the frantic gestures as they attempted to comprehend what had happened. One soldier vomited. Another began firing blindly into the jungle, emptying his magazine at shadows.

The Australians watched all of this. They did not engage. They simply observed as [music] the Vietkong collected their dead and retreated at twice the speed they had arrived, abandoning all pretense of tactical discipline. Morrison’s report concluded with a single observation that would echo through classified intelligence assessments for years.

Australian SAS does not conduct ambushes. They conduct psychological warfare operations using enemy bodies as the primary medium of communication. Effectiveness unprecedented. Recommend detailed study [music] of methods. Personal recommendation. I do not wish to participate in future joint operations.

But Morrison had only witnessed the surface. The true depth of Australian methodology [music] would not become apparent until the longhai operation of October 1968 when the full machinery of SAS reconnaissance doctrine revealed itself. The long high operation began with an intelligence assessment that American analysts had dismissed as impossible.

Australian signals intercepts suggested that D445 battalion had established a regimenalssized headquarters [music] complex within the mountains cave system. a complex housing not only combat troops but a fully functional field hospital, political cadre training center and arms [music] cache sufficient to sustain operations for 6 months.

American response options were limited. B-52 strikes [music] had proven ineffective against the deep cave networks. Helicopter assault was suicide given the anti-aircraft positions covering every approach. Ground operations required forces that third marine division could not spare without compromising positions elsewhere in the Australian solution was elegant in its simplicity and terrifying in its implications.

Rather than attempt to destroy the complex, they would map it every entrance, every exit, every supply route, every personnel movement. And they would do so using fiveman patrols operating inside the Vietkong’s own security perimeter for periods of up to 3 weeks. Over the following four months, Australian SAS conducted 17 long range reconnaissance patrols into the Long High Mountains.

The intelligence they gathered would eventually fill over 3,000 pages of classified reports. But more significantly, their presence inside the Forbidden Zone would have an effect that no amount of bombing could have achieved. The Vietkong began seeing ghosts. The phenomenon started with centuries reporting movement that left no trace. Guards would hear sounds.

a single snapped twig, a rustle of vegetation, but find nothing when they investigated. Patrol routes that had been used safely for years suddenly became death traps with soldiers disappearing during routine movements. The D445 battalion’s operational log from this period captured after the war reveals a unit descending into collective paranoia.

Entry from November 3rd, 1968. Three comrades failed to return from water collection. Search found no bodies, no blood, no evidence of contact. Political officer suspects desertion. Commander believes otherwise. Entry from November 7th. Sentry position 4 reported presence in jungle at 0200. Flare illumination revealed nothing.

Sentry found at dawn. Throat cut. No sound heard by adjacent positions 15 m away. Entry from November 12th. Movement restricted to daylight hours only. [music] Commander requests reinforcement from 274th regiment. Request denied. [music] Area considered secure from American operations.

But the area was not secure from Australian operations. And what the D445 battalion did not know, could not comprehend, was that the men hunting them had learned their craft not from militarymies, but from trackers whose ancestors had been pursuing prey through hostile terrain since before the pyramids were built. Private Walker had identified 17 separate runs through the Longhai jungle, habitual paths used by Vietkong personnel moving between cave complexes.

Like animal trails in the bush, these runs represented the accumulated wisdom of hundreds of movements, the paths of least resistance through dense vegetation. And like any hunter, Walker knew that the best place to wait for prey was along these runs. The Australians did not attempt to close these paths or ambush every movement.

That would have been inefficient. Instead, they selected two or three high-value runs and turned them into killing grounds, striking unpredictably and then withdrawing before the enemy could respond. The effect was not measured in body count, though Australian kill ratios in the long high would eventually reach 17 to1, but in psychological degradation.

By December of 1968, D445 battalion had effectively ceased offensive operations. Their strength had not been significantly reduced. Their supplies remained adequate. Their weapons were functional, but their will had been broken by an enemy they could not see, could not understand, and could not fight. This brings us to the central question that American military historians have debated for decades.

Why were Australian methods so [music] effective where American methods had failed? The answer lies not in technology or training, but in philosophy. American military doctrine of the 1960s was built on the assumption that superior firepower equals superior results. More bullets, more bombs, more helicopters, more troops.

If something is not working, add more of it until it does. Australian doctrine emerged from a different tradition entirely. [music] The tradition of small wars, colonial policing, and frontier survival. The Australian military had spent a century operating on the margins of empire, fighting enemies who could not be overwhelmed with firepower [music] because there was no firepower to overwhelm them with.

The Boore War, the Malayan Emergency, the Indonesian confrontation. In each of these conflicts, Australian forces had learned that patience, fieldcraft, and psychological manipulation could achieve results that artillery barges could not. But there was something else, something that American observers struggled to articulate.

The Australians seemed to approach jungle warfare with a different emotional register entirely. Where American soldiers often displayed anxiety, frustration, or fear in the bush, Australian SAS operators appeared almost comfortable. They moved through triple canopy jungle the way [music] a farmer moves through his own paddic with familiarity, confidence, and an almost proprietary sense of ownership.

Captain Morrison’s final report submitted in January of 1969 attempted to capture this difference was quote true. This was the revelation that American special operations would spend decades attempting to replicate with mixed success. The jungle was not the enemy’s weapon. It could be yours if you were willing to become something other than a conventional soldier.

The transformation of ordinary Australians into jungle phantoms did not happen by accident. It was the product of a selection and training process so brutal that American observers who witnessed it recommended against attempting [music] replication in US forces. Australian SAS selection began not with physical tests but with psychological evaluation.

Candidates were assessed for a specific personality [music] profile, high pain tolerance, low need for social validation, above average pattern recognition, [music] and what psychologists termed predatory patience. The ability to remain motionless for hours while maintaining complete situational awareness, the willingness to act with explosive violence after extended [music] periods of inactivity, the capacity to function independently in environments where help was days [music] away.

Only one in 12 candidates who began selection completed it. Those who passed entered a training program that would [music] last 18 months, three times longer than US Army special forces training of the same era. [music] And a significant portion of that training took place not in jungle warfare schools, but in the Australian outback, [music] learning tracking techniques from Aboriginal instructors whose methods had never been written down.

The cut boot ritual that so shocked American observers [music] was merely the visible symbol of this transformation. Australian SAS operators removed the soles from their standardisssue boots because hard leather and rubber created noise and left [music] distinctive prints. They walked on strips of tire rubber cut to match the profile of Vietnamese sandals.

From a distance, from a tracking perspective, they did not exist as Australians at all. They had become something else. Creatures of the bush who happened to carry western weapons. But perhaps the most disturbing aspect of Australian SAS operations, the element that resulted in several American liaison officers requesting transfer, was their approach to psychological warfare.

The body display doctrine had no official name in Australian military documentation. It existed only in the classified annexes of afteraction reports, in the whispered conversations of men who had witnessed it, and in the nightmares of Vietkong soldiers who survived encounters with the Maung, the jungle ghosts. The principle was simple.

Every engagement with the enemy was an opportunity for communication, not communication with headquarters, communication with the enemy themselves. And the most powerful message that could be sent was one that exploited the deepest fears of Vietnamese peasant soldiers raised on folktales of forest spirits and vengeful ghosts.

Australian SAS operators did not simply kill enemy soldiers. They staged their deaths. Bodies were positioned in ways that suggested supernatural intervention. Weapons were placed to indicate the victim had seen something terrible in his final moments. playing cards. The ace of spades, which Vietnamese superstition associated with death omens, were left as calling cards.

In some cases, operators would infiltrate enemy positions at night and leave signs of their presence without engaging. Footprints that appeared from nowhere and [music] led to nothing, equipment rearranged while guards slept, messages scratched into tree bark. The effect on Vietkong morale was devastating.

Political officers reported increasing difficulty maintaining unit cohesion in areas where Australian SAS operated. Desertion rates spiked. Soldiers refused night patrol assignments. Some units began conducting [music] elaborate spiritual rituals before entering jungle zones where the phantoms were known to operate. American observers were divided on the ethics of these methods.

Some, like Captain Morrison, viewed them as uncomfortably close to the psychological torture techniques they had been trained to consider violations of the laws of war. Others recognized their effectiveness and attempted to implement similar programs, most notably the death card initiative that saw American units distributing Ace of Spades playing cards throughout Vietnam.

But the American imitation missed the essential point. Leaving a calling card on a body you have killed is theater. Leaving a calling card on a body you have staged to communicate a specific message is psychological warfare. The Australians understood this distinction. Most Americans did not. By the spring of 1969, the Longhai mountains had effectively become Australian territory.

Not because the Vietkong [music] had been eliminated. They remained in their cave complexes. Nursing reduced capabilities and shattered morale. But because the Australians had achieved something American, forces had not managed anywhere in Vietnam. Psychological dominance over a defined area of operations.

The evidence could be seen in capture documents, in interrogation reports, in the observable behavior of enemy units operating in Fui province. D445 battalion had been neutralized not through attrition but through terror. Their soldiers refused to patrol in areas where Australian SAS had been reported. Their commanders issued orders that went unexecuted because [music] subordinates were too frightened to enter the jungle.

Their political cadre struggled to maintain the narrative of inevitable victory when men were disappearing from positions that should have been secure. But this success came at a cost that Australian authorities would spend decades attempting to minimize. The men who learned to hunt humans in the Longhai mountains did not simply return to sheep farming and factory work when their tours ended.

They carried something with them, a psychological adaptation to violence that civilian society could not accommodate. Post-traumatic stress rates among Australian Vietnam veterans would eventually exceed those of their American counterparts despite serving in smaller numbers and sustaining fewer casualties. The same transformation that made them devastatingly effective operators made them strangers in their own communities.

They had learned to think like predators, and predators do not easily return to the herd. The final American assessment of Australian SAS operations in Vietnam would not be completed until 1974, 3 years after the last Australian combat troops departed. Classified top secret and distributed to fewer than 50 recipients, the report reached conclusions that contradicted everything American military doctrine had assumed about counterinsurgency warfare.

First, small unit operations conducted by highly trained personnel achieved better results than large unit operations supported by overwhelming firepower. the Australian SAS kill ratio of 17 to1 compared to a MAC VOG average of approximately [music] 7 to1 and a conventional infantry average of approximately 1:1.

Second, indigenous tracking methods, specifically Aboriginal techniques adapted to jungle warfare provided intelligence capabilities that no technological system could replicate. Proposals to recruit Native American trackers for similar programs were submitted but never implemented. Third, psychological warfare operations targeting enemy morale could achieve strategic effects disproportionate to the resources invested.

A single fiveman patrol [music] operating for two weeks could degrade enemy effectiveness more than a battalionized sweep and clear operation. Fourth, and most controversially, Australian methods achieved these results while operating under significantly fewer restrictions than American forces. The classified annex noted that certain Australian practices regarding treatment of enemy [music] dead and conduct of psychological operations would likely violate standing MACV directives if [music] conducted by US personnel.

This final point would ensure that the report remained classified for decades. The Pentagon had no interest in publicizing the fact that their most effective allies in Vietnam had succeeded partly by doing things American forces were prohibited from doing. The political implications were too dangerous. The moral implications were too uncomfortable.

Better to let the Australian contribution fade into historical obscurity, remembered only by the veterans who had served alongside them. But history has a way of preserving what authorities wish to forget. In the decades following the Vietnam War, fragments of the Australian SAS [music] story began emerging through veteran memoirs, declassified documents, and academic research.

Each revelation added another piece to a puzzle that [music] contradicted the official narrative of Allied operations. The Long High Mountains, [music] the Forbidden Zone, where American Marines were not permitted to operate, became a symbol of something larger, the limits of American military doctrine, and the existence of alternative approaches that challenge fundamental assumptions about how wars should be fought.

>> [music] >> Today, special operations forces around the world study Australian SAS methods from Vietnam as examples of unconventional warfare at its most effective. The tracker programs, the psychological operations, the long range patrol doctrine, all have been incorporated into modern special forces training.

What was once classified as too controversial to acknowledge has become standard curriculum at Fort Bragg and Coronado. [music] Yet, something has been lost in the translation. Modern special operations can replicate Australian tactics. They struggle to replicate Australian psychology. The transformation that turns sheep farmers into jungle phantoms.

The [music] willingness to become something other than conventional soldiers. The acceptance that effective hunting requires becoming a hunter in your soul and not merely in your training. Private Dorian Walker returned to Australia in 1970 and never served in the military again. He spent his remaining years in the western desert living among his people, never speaking about what he had done in Vietnam.

When researchers attempted to interview him for academic studies of Aboriginal contributions to the war effort, he refused. “That knowledge belongs to the jungle,” he reportedly told one persistent historian. “It stays there.” “Captain William Dundis remained in the Australian Army until 1982, commanding SAS units through the postvietnam reorganization.

His classified lectures on jungle warfare methodology remain required reading at the Australian Defense Force Academy. He passed away in 2015. His full contribution to Australian military history still partially classified. And Captain James Morrison, the American observer who witnessed things in the Longhai mountains that changed his understanding of warfare forever.

He completed his tour with a MAC [music] SOG, returned to the United States, and never spoke publicly about his experiences with Australian SAS. His afteraction reports, however, survived in the classified archives, a testament to methods that American military doctrine was not prepared [music] to adopt and Australian authorities were not prepared to acknowledge.