In the late autumn of 1887, in a small, tight-knit settlement on the edge of the northern frontier, a man named Elias Thorne did something that made the entire town question his sanity. Elias was a quiet man, a newcomer who had bought a small, drafty cabin on the windiest hill in the valley. He didn’t speak much at the general store, and he didn’t join the men at the tavern to complain about the harvest.

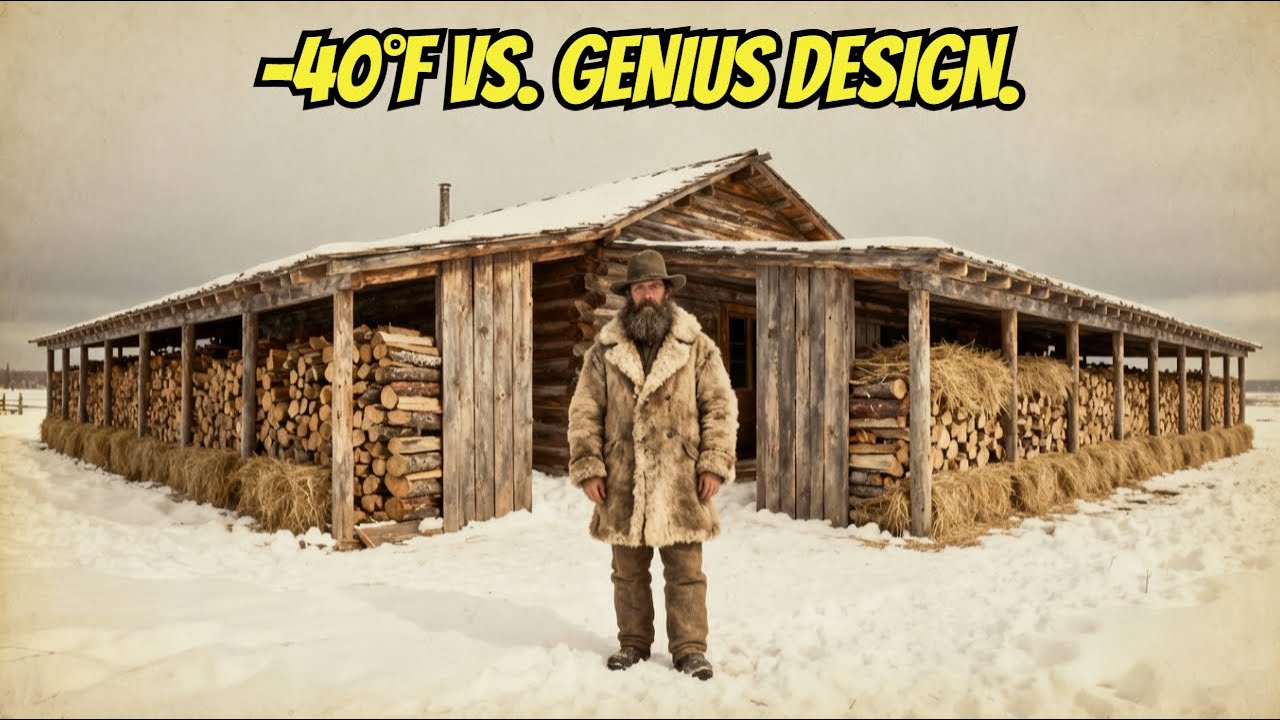

Instead, he spent every waking hour of October doing something that looked completely ridiculous. While everyone else was busy chopping wood and tossing it into piles near their back doors, Elias was building a massive ugly wooden frame that completely surrounded his house. It wasn’t a fence. It wasn’t a barn. It looked like he was building a shed around his cabin.

He extended the roof of his house out by 4 feet on all sides, creating a strange dark overhang that blocked the sunlight from his windows. Then he started stacking his firewood, but he didn’t stack it in a pile. He stacked it vertically, walling himself in. He stacked the logs from the ground all the way up to the new roof line, tightly packing every inch of space between the overhang and the ground.

To the neighbors passing by on their wagons, it looked like Elias was burying himself alive inside a wooden tomb. They slowed their horses to point and laugh. Look at him. They would sneer. He’s blocking out his own view. He’s going to be living in a cave all winter. The local carpenter, a man who prided himself on proper building methods, publicly mocked Elias.

He told anyone who would listen that Elias was a fool who was trapping moisture against his house which would surely rot the walls by spring. Wood needs to breathe, the carpenter said with a smug grin. Elias is building a box. He’ll be begging for help when his roof collapses. Chop, split, stack, chop, split, stack. But Elias didn’t stop.

He worked with a strange rhythmic intensity. He didn’t just stack the wood loosely. He fit the pieces together like a puzzle, creating a solid wall of oak and maple that was 2 ft thick. He did this on the north side. He did it on the west side. From the road, his home just looked like a giant windowless block of firewood.

He went all the way around until his actual house was completely invisible. He left only a narrow tunnel-like gap for his front door. Dot. By mid November, the laughter had turned into genuine confusion. Why would a man work so hard to make his house so dark and ugly? The town’s people felt a mix of pity and arrogance.

They had their neat wood piles stacked 20 ft away from their homes, just like their fathers and grandfathers had done. They had their drafty windows clear to see the snow falling. They felt civilized. Elias, in their eyes, had reverted to something primitive. He looked like an animal retreating into a burrow. One evening, a neighbor named Thomas rode up to Elias’s property.

Thomas was a kind man, but he was convinced Elias was making a mistake. “Alias,” he called out, his breath steaming in the cold air. “You’re blocking the sun, man. It’s going to be freezing in there without the sun hitting your walls. And how are you going to get the wood when it snows? You’ll have to tear down your own walls just to burn them.

” Elias paused, wiping sweat from his forehead. He looked at the gray sky, which was heavy with the promise of a winter unlike any they had seen before. He looked at Thomas and spoke one of the few sentences anyone ever heard him say. “The sun doesn’t warm you when the wind is blowing, Thomas. And I won’t be going out to get the wood. The wood is coming in to me.

” Thomas rode away, shaking his head, recounting the conversation at the tavern later that night. The men roared with laughter. He thinks the wood is going to walk inside. They joked. They raised their glasses, confident in their traditional ways, completely unaware that the barometer was dropping faster than it ever had in the history of the territory.

The winter of 1888 was knocking on the door, and it wasn’t polite. The skies were turning a bruised purple, and the birds had stopped singing days ago. While the town laughed at the Moleman on the hill, the air pressure plummeted, signaling the arrival of a storm that history books would later call the Great White Hurricane.

If you enjoy real historical stories about survival and forgotten ingenuity, make sure to like this video and subscribe. It helps us find more incredible stories like this one to share with you. The laughter died instantly on the morning of January. It didn’t fade away. It was silenced by a sound that most of the settlers had never heard before.

Screaming wind that sounded like a freight train tearing through the valley. The temperature didn’t just drop, it crashed. In the span of a few hours, the mercury plunged from a mild freezing point to 40° below zero. This was the flash freeze of the great blizzard, a weather event so sudden and violent that chickens were frozen solid in their tracks before they could reach the coupe.

For the people of the town, the reality of the storm was terrifying. The wind wasn’t just cold, it was a physical weapon. It drove the snow horizontally, packing it into every crack and crevice of their homes. The civilized houses with their exposed walls and clear windows immediately failed. The glass in the windows froze over with thick ice on the inside.

The wind hammered against the siding, sucking the heat right out of the rooms. Families huddled around their wood stoves, feeding them frantically. But it felt like they were trying to heat the outdoors. The heat was being stripped away faster than the fire could create it. Then came the problem of the firewood.

Remember those neat wood piles the neighbors were so proud of? They were stacked 20 or 30 ft away from the houses. In normal weather, that was just a minor inconvenience. Dot. In a blizzard with 70 mph winds and zero visibility, it was a death sentence. To get more fuel, the men had to bundle up, tie a rope around their waist so they wouldn’t get lost in their own backyards, and fight their way through chest deep drifts.

His wood pile was buried under six feet of hardpacked snow. Thomas, the neighbor who had mocked Elias, found himself in a nightmare. Every time he went out to retrieve a few logs, the wind bit his exposed skin, turning it white with frostbite in seconds. He would drag the wet, frozen logs back into the house, his hands shaking so badly he could barely strike a match.

And when he finally got the wood into the stove, it hissed and popped. It was wet. The snow had driven into the pile, soaking the bark. Wet wood burns poorly. It creates smoke instead of heat. So Thomas sat in his smoke-filled, freezing living room, his children shivering under piles of blankets, wondering if they would survive the night.

Meanwhile, up on the hill inside the wooden tomb, the situation was shockingly different. Elias was sitting in his rocking chair, reading a book by the light of a kerosene lamp. He wasn’t wearing a heavy coat. He wasn’t shivering. In fact, he was perfectly comfortable. The ridiculous shed he had built around his house was doing exactly what he had planned. Dot.

The two-ft thick wall of firewood acted as a massive insulation barrier. In modern engineering, this is called a thermal envelope. The wind slammed against the outer layer of firewood, but it couldn’t penetrate the solid mass of logs. The air trapped between the logs and the actual house wall became a dead airspace, the best insulator in the world.

While the wind outside was screaming at 40 below zero, the actual wall of Elias’s cabin was untouched by the gale. The heat from his small stove stayed inside, radiating back off the walls instead of being sucked away. But the true genius of Elitus’ design was revealed when his stove needed more fuel. When Thomas was risking his life to dig frozen logs out of a snowbank, Elias simply stood up, walked to his door, and opened it.

He didn’t step outside into the blizzard. He stepped into the sheltered tunnel created by his extended roof. There, stacked neatly against his wall, was his firewood. It was perfectly dry. It was protected from the snow by the roof overhang. Elias simply reached out, pulled a few dried seasoned logs from the wall right next to his door, and walked back inside.

He didn’t even have to put on his boots. As he burned the wood, he was slowly dismantling the insulation layer from the inside. But it didn’t matter. The outer layers of the stack still blocked the wind. He was literally consuming his fortress to stay warm. And because the wood was dry, it burned hot and clean. Down in the valley, the storm raged for 3 days.

The noise was deafening. Houses creaked and groaned under the pressure. Some roofs collapsed under the weight of the snow. The cold was relentless. People burned their furniture when they couldn’t reach their wood piles. They burned their floorboards. They prayed for the wind to stop.

They thought of Elias on the hill and assumed the worst. The fool. They thought he’s probably frozen solid in that cave of his. No one could survive this exposed on the hill. He wished he had dragged Elias down to his house before the storm hit. He imagined the silence up on the hill, the snow burying the strange wooden box, turning it into a grave.

He promised himself that if they lived through this, he would give Elias a proper burial when the snow melted. But the storm wasn’t done yet, and the biggest surprise was waiting for them when the sun finally rose. What would you have done in this situation? Would you have risked the new building method or stuck to tradition? Let me know in the comments below.

When the wind finally died down on the fourth morning, the silence that fell over the valley was heavy. The sun came out, illuminating a world that had been transformed into a white frozen wasteland. The snow drifts were so high that people had to tunnel out of their second story windows just to escape their homes. The town was battered.

Chimneys had toppled. Windows were shattered. Survivors emerged slowly, their faces gaunt and pale. Traumatized by the cold that had nearly killed them. A group of men, including Thomas, gathered their strength to check on the neighbors. They moved from house to house, helping those who were trapped, sharing what little dry food they had left.

But there was one destination they were dreading. The hill. We have to go check on Elias, Thomas said. his voice raspy from the smoke of his struggling stove. The other men nodded grimly. They grabbed shovels and a sled, fully expecting to bring back a body. The hill was the most exposed point in the valley. The windchill up there would have been unservivable for a normal cabin.

They trudged up the slope, fighting through waist deepep snow as they neared Ilas’s property. They stopped in their tracks. The wooden fortress was buried almost to the roof in a massive drift shaped by the wind. It looked like a giant igloo made of snow and timber. There was no smoke coming from the chimney. Thomas’s heart sank. “The fire is out,” he whispered.

“He’s gone.” They reached the tunnel-like entrance Elias had built. It was blocked by a wall of snow, but because of the overhang, the snow hadn’t packed tight against the door itself. They began to dig frantically, shouting Elias’s name. “Ilas! Elas!” No answer. Thomas broke through the last drift and hammered on the wooden door.

“Alias! It’s Thomas. Can you hear me?” Silence. Then they heard a sound. It was the scraping of a latch. The door creaked open. He held a mug of steaming coffee in one hand. “Morning,” Elias said calmly. “Storm’s over.” Then, Thomas stood there, his mouth a gaped, staring past Elias into the cabin. He could see the stove glowing with a steady hot fire.

He could see that the interior was cozy. But what shocked him most was the firewood. His firewood had never been wet. It had never been cold. While the town’s people had been freezing their hands off trying to dig wet logs out of the snow, Elias had simply plucked dry fuel from his walls.

It had been waiting for him, protecting him. The men didn’t laugh this time. They didn’t sneer. They walked into his home, shivering, and warmed their hands by his stove. They asked him how he had done it. Elias explained the simple physics that the civilized world had forgotten. “The wood is insulation,” he told them. It holds the heat. It stops the wind.

And because the roof covers it, the wood is always ready to burn. I didn’t fight the winter. I wore it. The neighbor who had mocked him, the carpenter arrived later that afternoon. He walked around the structure, touching the dry wood, feeling the warmth radiating from the house. He didn’t say a word about rotting walls or wood needing to breathe.

He simply took off his hat and nodded at Elias. It was a silent admission of defeat and of respect. In the years that followed, the architecture of the valley changed. You didn’t see many exposed cabins on the windy hills anymore. They started respecting the old ways of insulation that Elias had brought with him.

Elias Thorne didn’t become a mayor or a hero in the newspapers. He remained the quiet man on the hill. And when Elias started stacking his wood, the neighbors didn’t laugh. They picked up their axes and they started stacking theirs, too.