September 28th, 2008. St. Mark’s Church, Westport, Connecticut. Robert Redford stood at the pulpit looking down at 2,000 people. Paul Newman’s casket sat 15 ft away. Redford cleared his throat. Paul called me kid for 40 years, he said. A few people smiled through their tears. Everyone in that church knew about the nickname, the affectionate teasing, the running joke that had lasted four decades.

I finally figured out why, Redford continued. The church went completely silent. What Redford said next made 2,000 people laugh and cry at the same time. And it revealed something about their friendship that nobody had understood until that moment. To understand why that eulogy became legendary, you need to go back to where it started.

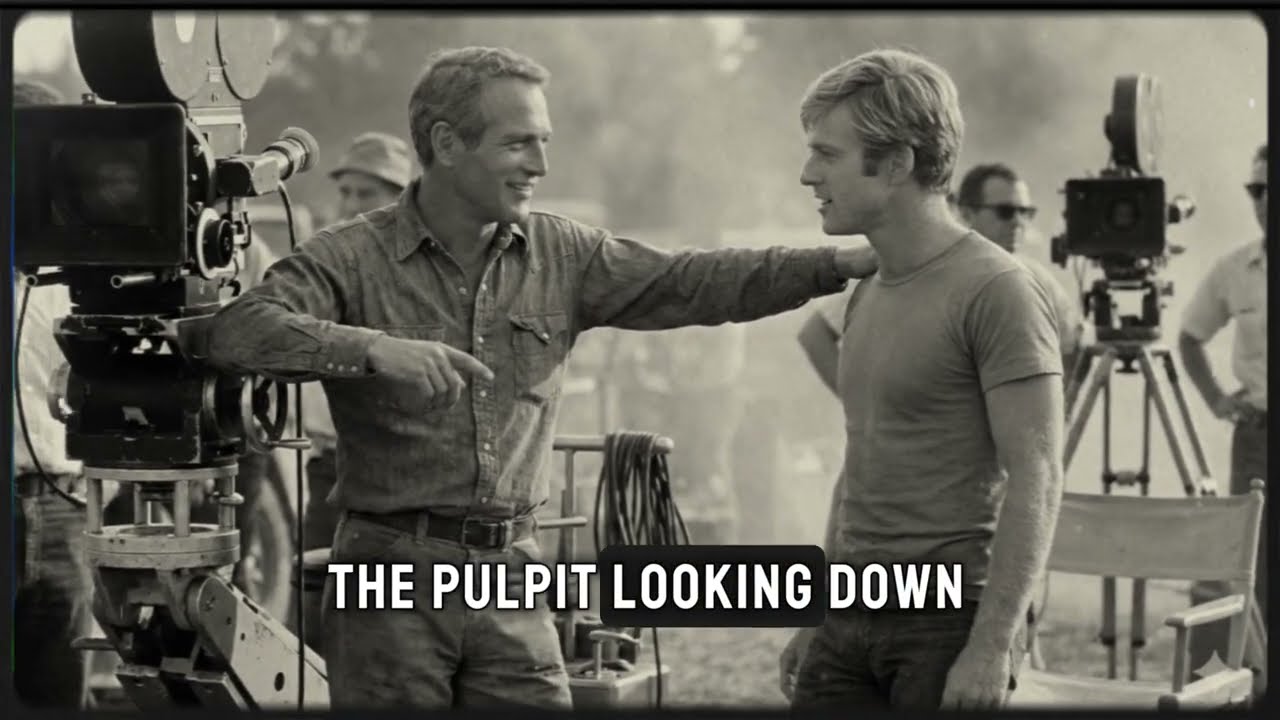

March 1969, the set of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. Robert Redford was 32 years old. He’d done some television, a few small film roles, but nothing that made him a star. He was talented, handsome, but unknown. Paul Newman was 44. He’d already starred in The Hustler, Cool Handluke, Hud. He was one of the biggest names in Hollywood, an icon.

The first day on set, Redford was nervous. He’d heard stories about Newman, the intensity, the perfectionism, the blue eyes that could freeze you if you weren’t prepared. Director George Roy Hill called them together for the first rehearsal of the train robbery scene. Newman walked over, extending his hand. Paul Newman. But you already know that. Redford shook it.

Robert Redford, but you might not. Newman smiled. I know who you are, kid. George wouldn’t shut up about you, kid. It was casual, friendly, maybe even affectionate, but something about it made Redford pause. I’m 32, Redford said. Newman laughed. And I’m 44, which makes you the kid. He slapped Redford on the shoulder.

They don’t worry, you’ll grow into it. What Redford didn’t know was that Newman had fought for him to get this role. The studio had wanted Warren Batty or Marlon Brando. Big names, safe choices. But Newman had told them, “It’s Redford or I Walk.” He’d seen something in Redford, something the studio executives couldn’t see yet.

A quality that would make Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid one of the greatest buddy films ever made. And from that first day, Newman called him kid. Not Robert, not Redford, kid. The first week of filming, they shot the famous cliff jumping scene, the one where Butch and Sundance are cornered by the posi and have to jump into the river below.

They were standing on a cliff edge, looking down at the raging water. Well, not the actual cliff. that would be done with stunt doubles and special effects. But they were rehearsing the scene on location and Newman wanted to feel the height. “You thinking what I’m thinking?” Newman said, delivering Butch’s line.

“I hope not,” Redford replied as Sundance. Newman grinned. “Come on, kid. One take. Real jump. They’ll love it.” Redford looked at him. “You’re serious?” “Dead serious. You’re also insane.” Newman laughed. Maybe. But that’s why this is going to be the best movie either of us ever makes. He looked down at the water.

What do you say, kid? You trust me? And here’s the thing. Redford did trust him. This man he’d known for 5 days. This Hollywood legend who could have made him feel small, but instead made him feel like an equal. They didn’t jump. George Roy Hill shut that idea down immediately. But the trust, that was real. By the end of filming, they’d become friends.

Not Hollywood friends. real friends, the kind who called each other at 2 in the morning just to argue about baseball or politics or which whiskey was better. And every single conversation started the same way. Hey kid, you busy? Listen, kid. I need your opinion on something. Not bad, kid. Not bad at all.

September 1969, Butch Cassidy premiered in New York. The critics loved it. The audience loved it. It would go on to make over a hundred million dollars. A massive hit. At the afterparty, Newman found Redford on the balcony looking out at the city. You okay, kid? Redford turned. Stop calling me that.

Newman raised his eyebrows. Calling you what? Kid, I’m 33 years old, Paul. I just co-starred in the biggest movie of the year. I’m not a kid anymore. Newman was quiet for a moment, then he said, “You’re right. You’re not a kid, but you’re my kid, and that’s different.” Redford didn’t understand what that meant. Not then. But 3 years later, something happened that made it clearer. 1972.

Robert Redford was directing his first film, Ordinary People. It was a small personal story about a family dealing with grief and loss. Nothing like the big action movies or romantic comedies Hollywood wanted. Studios kept turning it down. Too dark, too quiet, too risky. Redford was starting to doubt himself.

Maybe they were right. Maybe he wasn’t ready to direct. Maybe he should stick to acting. The phone rang at midnight. “You thinking about quitting, kid?” Redford sat up in bed. “How did you know?” “Because I know you,” Newman said. “And I know that when things get hard, your first instinct is to walk away before anyone can tell you that you weren’t good enough.

” “Paul, I don’t think I can do this,” Bull, you can absolutely do this, but you’re scared, and that’s okay. Being scared means you care about getting it right. Newman paused. Here’s what we’re going to do tomorrow morning. You and I are going to sit down and go through your script, every scene, every line, and we’re going to figure out exactly how you’re going to make this movie because you are going to make it, kid, and it’s going to be great.

They spent three days together. Newman didn’t just encourage Redford. He challenged him, pushed him, made him defend every creative choice until Redford believed in them completely. Ordinary people got made. And in 1981, it won the Oscar for best picture and best director. At the ceremony, when Redford’s name was announced, the camera caught Paul Newman in the audience.

He was on his feet before anyone else, clapping, smiling, tears in his eyes. Backstage after the ceremony, Newman found Redford. Proud of you, kid. Redford held the Oscar. Paul, I’m 44 years old, the same age you were when we met. Are you ever going to stop calling me that? Newman looked at him. Probably not.

Why? Newman thought about it. Because no matter how old you get, no matter how many Oscars you win, you’re always going to be the guy who walked onto the Butch Cassidy set, nervous as hell, trying to prove he belonged. And I’m always going to be the guy who already knew you did. The years passed. They made another movie together.

The Sting, another massive hit, more late night phone calls, more arguments about nothing important and everything that mattered. Redford built Sundance. Newman started his food company giving millions to charity. They lived separate lives but stayed connected. And every conversation, every reunion, every phone call started the same way. Hey kid, 1998.

Redford was 61 years old, a grandfather, a legend in his own right. He was at a charity event in New York when his phone rang. Kid, where are you? Paul, I’m at a gala. What’s wrong? Newman was quiet for a moment. Nothing’s wrong. I just wanted to hear your voice. Something in Newman’s tone made Redford step out of the ballroom into the hallway.

Paul, what’s really going on? I’m getting old, kid. We both are. And I was sitting here thinking about all the people I’ve known, all the movies I’ve made, all the things I’ve done. And you know what I realized? What? The best thing I ever did was fight for you to get that role in Butch Cassidy.

Not because the movie was good, because I got to know you. Because I got to be your friend. Redford felt his throat tighten. “Paul, are you dying?” Newman laughed. “Not today, but someday. And when I do, I want you to do something for me. Anything. Don’t be sad. Don’t give some boring, serious eulogy about my career and my achievements. Just tell them the truth.

Tell them I called you kid for 40 years.” And tell them why. Why did you call me kid? Paul, you’ll figure it out, kid. When the time comes, you’ll know. 10 years later, the time came. September 26th, 2008. Paul Newman died of lung cancer at his home in Westport, Connecticut. He was 83 years old.

Redford was in Utah when he got the call. He’d known it was coming. Newman had been sick for months, but knowing didn’t make it easier. He flew to Connecticut for the funeral. Joanne Woodward, Newman’s widow, asked him to give the eulogy. Paul wanted you to, she said. He told me years ago if anything happened to him, you had to be the one to speak.

September 28th, 2008, St. Mark’s Church. Redford had written and rewritten his eulogy a dozen times. Nothing felt right. Every version was too formal, too safe, too much like every other celebrity eulogy. The night before the funeral, he threw them all away and wrote one sentence. That was all he needed.

He stood at the pulpit looking at the casket at the 2,000 people waiting at Joanne in the front row, tissues pressed to her eyes. Paul called me kid for 40 years, he said. And he meant to continue right away, to move into his prepared remarks. But something stopped him. The memory of every time Newman had said it, every phone call, every reunion, every moment of doubt when Newman’s voice would cut through the noise.

Hey kid, I finally figured out why. Redford said the church was so quiet he could hear his own breathing. He looked at the casket, at his friend, at the man who’d believed in him before anyone else did because he never wanted me to grow up and realize I was the better-l looking one. For a moment, nothing happened.

Then someone in the back laughed. A single surprised laugh. than someone else. Then the whole church was laughing. Not disrespectful, rockous laughter, but the kind of laughter that comes from recognition, from knowing that Paul Newman, even in death, would have wanted the joke. And through the laughter, people were crying because they understood.

The nickname wasn’t about age. It wasn’t about hierarchy or mentorship or who was more famous. It was about preservation, about holding on to a moment, about refusing to let time steal the version of someone you loved most. To Paul Newman, Robert Redford would always be the nervous 32-year-old walking onto a movie set trying to prove he belonged.

The one who needed someone to believe in him, the one who needed to be reminded that he was good enough, talented enough, worthy enough. And Paul Newman had appointed himself that reminder for 40 years. Kid meant, “I see who you are, not what the world made you.” Kid meant, “No matter how famous you become, you’re still that person I fought for.

” Kid meant, “I believe in you. I always have. I always will.” Redford continued his eulogy. He talked about Newman’s charity work, his racing, his dedication to his family. But what everyone remembered was that opening, the joke that wasn’t just a joke, the nickname that wasn’t just a nickname. After the service, people came up to Redford.

I never understood why he called you that, one actor said. But now I do. My father used to call me by my childhood nickname, a director said. Even when I was 50, I hated it. But after hearing you today, I think I finally understand what he was really saying. A young actress, maybe 25, approached him with tears streaming down her face.

I hope I find a friend like that someday, she said. someone who sees me that way. Redford put his hand on her shoulder. You will, kid. The word slipped out naturally. He hadn’t planned it, but it felt right because he finally understood. Newman hadn’t just been preserving Redford’s younger self. He’d been teaching him how to do the same for others and how to see people not as they are but as they might become.

How to believe in them before they believe in themselves. How to be the voice that says you can do this when everyone else is saying you’re not ready. In the years after Newman’s death, Redford started using the word more. Not with everyone, but with young filmmakers at Sundance who reminded him of himself at 32. nervous, talented, unsure.

Hey kid, let me give you some advice. You did good, kid. Real good. Don’t quit on me now, kid. You’re just getting started. And every time he said it, he thought of Paul. Of that first day on the Butch Cassidy set, of 40 years of phone calls and arguments and laughter and support, of a friendship that transcended age and fame and everything Hollywood usually made complicated.

Newman called him kid because some part of us should always stay young, should always stay hungry, should always stay open to being shaped and challenged and believed in. The world wants us to grow up, to become serious, to lose the wonder and the doubt and the vulnerability that made us reach for impossible things. But Paul Newman refused to let Robert Redford do that.

For 40 years, he held on to that nervous 32-year-old actor and refused to let him disappear into the legend. kid was an anchor, a reminder, a gift. And at the funeral, when Redford made 2,000 people laugh and cry at the same time, he was passing that gift forward. He was saying, “This is what friendship looks like.

This is what belief looks like. This is what love looks like.” Not grand gestures, not public declarations, just one word repeated for 40 years. Paul Newman died at 83. Robert Redford is now 87. The same age Newman was when he died is approaching. In interviews, people still ask Redford about the nickname, about what it meant, about how he felt every time Newman said it.

Annoyed, Redford always says with a smile. But for the first 39 years, I was annoyed. And the 40th year, the 40th year, I understood. He understood that Paul Newman had given him something more valuable than any role or any Oscar or any amount of fame. He’d given him a version of himself to live up to. Not the polished, perfect version the world expected, but the raw, vulnerable, still becoming version that needed someone to say, “I believe in you, kid.

Now get out there and prove me right.” That’s what great friendships do. They don’t let us become smaller. They hold space for us to become more. They see our potential before we do and refuse to let us settle for less. And sometimes if we’re very lucky, they do it with just one word, repeated.

For 40 years, have you ever had someone in your life who saw you that way? Someone who held on to the version of you that still believed anything was possible? If you have, hold on to them. Tell them what they mean to you. Because that kind of friendship, the kind Paul Newman and Robert Redford had, is the rarest thing in the world. And if you haven’t found it yet, maybe you can be that person for someone else.

Maybe you can be the one who sees the nervous kid in the successful adult, the dreamer and the cynic, the believer in the doubter. Maybe you can be the one who says, “Hey kid, I see you and you’re going to be great.” If this story of 40 years of friendship and one perfect eulogy moved you, subscribe for more untold stories about the bonds that shaped Hollywood’s greatest legends.

Share this with someone who believed in you when no one else did. and leave a comment telling us about the person who saw your potential before you did. Don’t forget to hit that notification bell so you never miss these stories of the friendships that changed