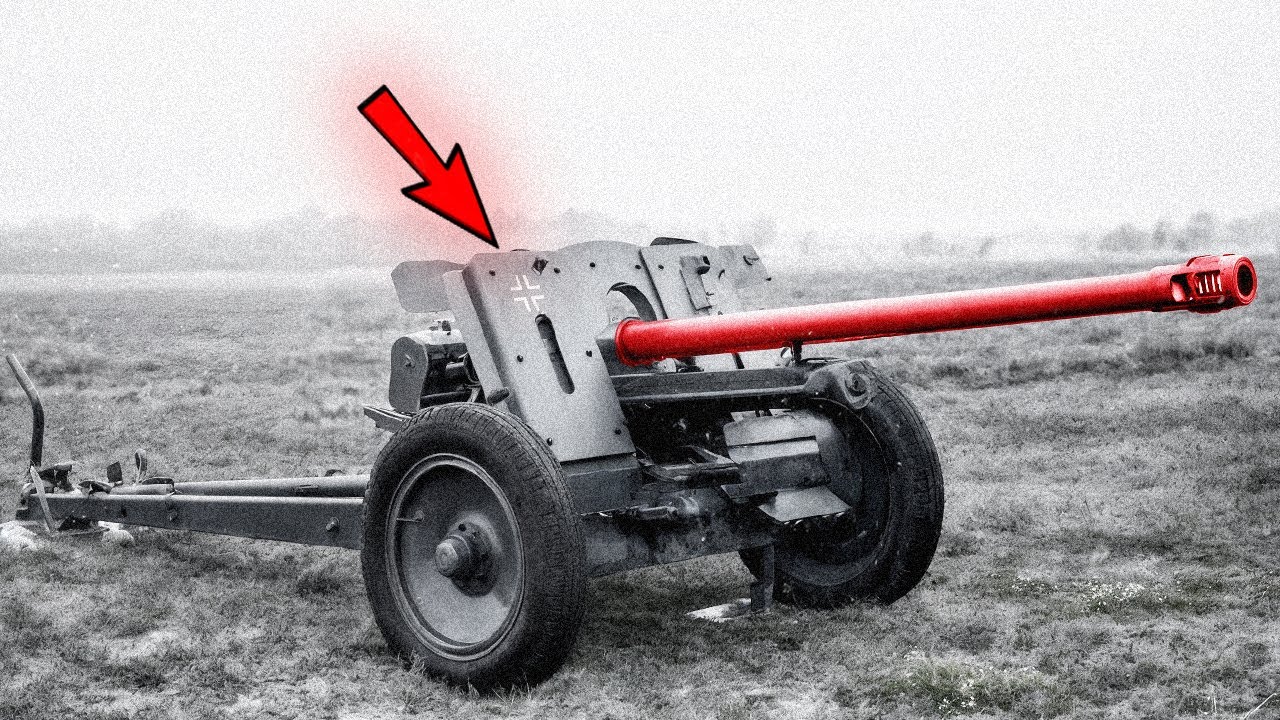

In June 1941, the German infantry had the world’s best anti-tank defense system. Lightweight, accurate, rapid fire PAC 36 guns had already proven their lethality in Poland and France. And nearly 13,000 of these machines formed the backbone of the Vermach’s anti-tank shield. However, just a few months later, soldiers began referring to them as door knockers.

This was because the only thing these guns were now good for was knocking on the armor of a Soviet tank and revealing their position a moment before being turned into a pulp of steel and flesh. To understand how Germany’s best anti-tank weapon became a death sentence for its own crews, you have to be on the country road between Oral and Masensk on a cold October morning when fog still hung over the fields.

The war seemed to be going exactly according to plan. On the 6th of October 1941, the advanced guard of the Vermach’s fourth panzer division passed the village of Kamvo and moved along the road to Tula. Behind them lay weeks of rapid advances, hundreds of thousands of prisoners, endless columns of burned out Soviet tanks that burst into flames at the first hit. ahead.

According to the calculations of the Army Group Center headquarters, there were 170 km left to Moscow, and nothing foreshadowed what would happen in the coming hours. They appeared from the woods on the left flank, vehicles of unfamiliar silhouette with long guns and strange sloped armor that seemed to flow down to the ground at an acute angle.

Colonel Male Katakov, whose division had been defeated in border battles three months earlier, had spent the whole night hiding his fourth tank brigade in ambush. He used tactics that would become a nightmare for German commanders. False positions, sudden strikes from cover, and immediate retreat to pre-prepared lines.

Now 30 T34s and KV tanks struck the flank of the German column. And for the first time, the Germans faced an enemy that did not fight by their rules. The PAC 36 crews turned their guns and opened fire. Everything was done by the book. Aim, fire, hit. The shell hit the front plate of the lead tank, kicked up a shower of sparks, and bounced off without even leaving a dent.

Second shot, third, fourth, and each time the 37 mm shells bounced off the sloped armor like peas off a wall. The Soviet vehicles did not slow down for a second. They drove through the explosions, through the hits, through everything that the German anti-tank defenses could throw at them and methodically fired at the gun positions with their 76 mm cannons.

The heavy guns mounted on the crest of the hill managed to knock out a few vehicles, but there were too few of them. The armored waves swept over the mountain, crushing the guns with its tracks and descended on the combat group’s tanks in close combat, where the German tankers had no chance. General Gudderion would later write that the fourth Panzer division was attacked south of Matsensk and went through several difficult hours and that it was then that the overwhelming superiority of the Russian T34 became abundantly clear. This was a

restrained description of a catastrophe that overturned all of the Vermach’s ideas about the enemy. In the days and weeks that followed, the scene near Matsensk was repeated across the front with frightening regularity. PAC 36 crews fired and hit, hit and fired again, watching as shells ricocheted off the sloped armor or got stuck in it without causing any damage.

There were reports of tanks that had withstood dozens of direct hits and continued to move. Caliber armor-piercing shells simply refused to penetrate the steel. In those rare cases when penetration did occur, the vehicle was not disabled as the fragments of a 37 mm shell were too small to hit the crew or damage the mechanisms. The physics were inexurable.

At a distance of 500 m, the pack 36 shell could penetrate about 30 mm of steel. The T34’s frontal armor was 45 mm thick. Still, it was angled at 60° to the vertical, effectively doubling its thickness. A gun designed for war against tanks of the 1930s faced a machine from another era and proved powerless against it.

Attempts to find a solution were made feverishly. Subcaliber PGR40 shells with a tungsten carbide core were sent to the front, which could penetrate the side of a T34 at close range. However, there was a catastrophic shortage of tungsten in Germany, and these shells were distributed one by one like precious jewels.

The only reliable salvation remained the 88 mm flack anti-aircraft guns whose heavy shells could pierce any armor. However, there were few anti-aircraft guns, and they were cumbersome. They required time to deploy and could not accompany the infantry in an offensive. Desperate recommendations appeared. Let the T34 get within 50 m and shoot at its side, aiming at the tracks, the stern, and the junction of the turret and hull.

[clears throat]All of this was advice for suicide bombers because at such a distance the Soviet tank had time to shoot the gun crew before they could fire a second shot. The artillery men who until recently it had felt like masters of the battlefield now experienced something akin to despair. They did everything right, followed every point of the regulations, achieved hits, and still died because their weapons had become useless pieces of metal.

Generals von Melanthan and Middorf would later call the PAC 36’s inability to fight the T34 a dramatic chapter in the history of the German infantry. And there was not a grain of exaggeration in this statement. However, the most frightening thing was not that the gun was powerless. The most frightening thing was that a year ago it was the best anti-tank gun on the planet.

To understand the scale of the disaster, we need to go back 15 years to the design bureaus of the Rhin Matal concern. The treaty of Versailles prohibited Germany from developing modern weapons. Still in the mid 1920s, engineers secretly began developing a weapon to fight tanks. The work was carried out under the cover of civilian projects and tests were conducted at secret test sites in the Soviet Union with which the VHimar Republic maintained tacet military cooperation.

37 mm. This was the caliber that the engineers chose as optimal and for its time it was a flawless decision. The tanks of that era were clumsy steel boxes with 15 to 20 mm of bulletproof armor and a 680 g shell leaving the barrel at 72 45 m/s could pierce such protection at 1 kilmter. At the same time, the gun itself weighed only 432 kg.

Two people could roll it across the battlefield by hand, turn it around in a matter of seconds, and fire at a rate of 15 rounds per minute. Compact, accurate, and deadly, it became the benchmark for anti-tank weapons, and its design was copied around the world. The Soviet Union used the PAC 36 gun carriage as the basis for its 45mm cannon.

The Japanese produced licensed copies and the Americans and British used the German caliber as a reference when developing their own systems. It saw its first combat in Spain in 1936. The guns of the Condor Legion rolled out in direct fire and shot down Republican T26 from a distance at which Soviet tankers did not even have time to understand where the fire was coming from.

A few seconds to aim a shot and the vehicle burst into flames. Shot through. Then there was Poland where no Polish tank stood a chance against these guns. Then France, where the PAC 36 dealt with most targets, although the British Matildas and French Char1s had already shown alarming resistance to its fire.

However, these vehicles were rare and the overall triumph of the Blitzkrieg overshadowed the first signs of impending doom. The German command was aware of the problem. Even after the French campaign, it became clear that the 37 mm caliber was becoming obsolete and Rhin Matal designers were already working on more powerful guns.

The 50 mm PAC 38 existed and even entered production. Still, factories produced it too slowly. And by the start of Barbar Roa, there were only about 1,000 of these guns in the army, compared to almost 13,000 obsolete PAC 36. The story with tank guns is telling. Hitler personally ordered that the new modifications of the Panzer 3 be armed with 50 mm guns.

Still, the Army Weapons Administration ignored the order and continued to install 37 mm guns, considering them sufficient. This self-confidence permeated the entire decisionmaking system. The philosophy of Blitzkrieg demanded lightness in a mass, not power. Heavy guns slowed the offensive, complicated logistics, and required tractors rather than horses.

An army that won in weeks could not afford to wait for industry to switch to a new caliber. Moreover, intelligence was reassuring. Reports of new Soviet tanks had been coming in since the spring of 1941. Still, the data on armor was catastrophically underestimated. Analysts estimated the frontal protection of the KV at 40 mm rather than the actual 75 mm.

They made no mention of the T34’s sloped armor, which doubled its adequate thickness. The decision seemed obvious. Start Barbarosa with what you have. The war will be short. The Soviets will collapse in a few months, and the caliber problem will resolve itself. It was a gamble that the Vermacht would lose, but in June 1941, no one knew that yet.

While German generals were counting the kilometers to Moscow, factories in Karkov and Stalenrad were rolling out vehicles that would turn this gamble into a death sentence. The first weeks of Barbar Roa confirmed the German strategists correctness. The PAC 36 mowed down Soviet tanks by the thousands and every day brought new confirmation of its effectiveness.

Entire tank armies were burned in the giant cauldrons of encirclement near Minsk, Smolinsk, and Kiev. BT7s burstinto flames from the first hit. T-26s fell apart and even the heavy multi-turreted T-28s and T35s were penetrated at medium ranges. A typical battle looked like this. Soviet tanks went on the attack in dense formations without reconnaissance or infantry cover and ran into the camouflaged positions of anti-tank battalions.

Small 37 mm guns opened fire from 600 to 800 meters, and the tanks began to burn one after another. The crews barely had time to reload, and the field in front of them was already covered with smoking wrecks. By December 1941, the Red Army would lose more than 20,000 tanks. And a considerable proportion of these losses would be accounted for by the anti-tank battalions of the infantry divisions armed with these very guns.

The figures look triumphant. The PAC 36 was capable of effectively destroying more than 90% of the Soviet tank fleet. In the first months of the war, this fleet consisted almost entirely of vehicles that it could destroy. The T34 and KV accounted for only 6% of the total number of Soviet tanks. 6% seemed like a statistical error that could be ignored.

6% of German artillerymen hardly ever encountered in battle, while the main forces of the Red Army were dying in giant encirclements. However, it was precisely these 6% that were already advancing to the front line, and soon they would change everything. German artillerymen celebrated their victories, unaware that every T-26 they destroyed brought them closer to encountering a machine against which they would not stand a chance.

In the fall of 1941, 6% ceased to be a statistic and became a nightmare. T34s and KV tanks appeared more and more often, and each encounter ended the same way. The PAC 36 crews did their job flawlessly, scoring hits, watching flashes on the armor, and dying under the tracks of tanks they couldn’t stop.

The nickname doornocker spread throughout the eastern front and it no longer sounded like bitter irony, but rather the despair of people betrayed by their own weapons. The shock of encountering the new Soviet tanks was so great that Gudderion demanded a special investigation. In November 1941, a commission arrived at the front between Oral and Msensk consisting of leading Reich designers and industrialists including Ferdinand Porsche and Erin Otter, the future creator of the Tiger tank. They examined

the damage at T34s, studied the traces of hits on the armor, and measured the angles of inclination and thickness of the steel. What they saw left no illusions. They were particularly struck by the quality of Soviet armor, which proved harder and more challenging than German armor. Despite all the talk about the enemy’s technical backwardness, frontline officers proposed a simple solution.

Copy the T34 and put it into production. However, the engineers rejected this idea, not out of pride, but out of an understanding of reality. Germany did not have enough aluminium to produce the quantities of diesel engines needed and German alloy steel was inferior to Soviet steel due to a shortage of raw materials.

Copying was impossible and meanwhile every day of delay cost lives. A response of their own was needed and it had to be immediate. The answer came in the form of programs that would change the face of German armored vehicles. The shock at Matsensk gave rise to the Panther and Tiger vehicles explicitly created to counter the T34 and KV.

At the same time, the Panther openly borrowed the main advantage of the Soviet tank, its sloped armor, which made the T34 invulnerable to German shells. New anti-tank guns appeared. The 75mm PAC 40 and then the monstrous 88 mm PAC 43 capable of penetrating any Allied tank at any reasonable distance. However, all these systems were delivered to the troops too late and in too small quantities to turn the tide of the war.

The lesson taught at Mitsensk was learned, but the time lost to overconfidence could not be regained. The fate of the PAC 36 was sealed on 29th of August 1942 when the Army general staff officially rejected the weapon. Production was curtailed and the remaining guns were gradually removed from anti-tank units armament.

Some of them were equipped with steel granite 41 overcaliber cumulative grenades capable of penetrating up to 180 mm of armor. There was a bitter irony in this. A weapon that was conceived as the embodiment of engineering perfection now needed an ugly crutch to do its job. Moreover, the firing range of these shells did not exceed 300 m, which made every shot a suicidal venture.

Other guns were transferred to parachute units and second line units where they served out their lives far from Soviet tanks. Several surviving examples of the PAC 36 are now on display in military museums around the world. From the Aberdine proving ground in the United States to Kubinka near Moscow. Small, elegant, almost toylike comparedto the guns that replaced them.

These exhibits from another era remind us of a time when 37 mm was enough to stop any tank on Earth. This story is not about destructive weapons. It is about an army that was so accustomed to winning that it failed to notice how the enemy was changing. German generals made plans based on what the enemy was yesterday, not what it would be tomorrow.

They saw burning T26 and BT7s, counted impressive casualty figures, and failed to notice that these victories were meaningless. Because the real war was not being fought with tanks from the 1930s, but with the factories of Karkov and Stalenrad, which everyday produced machines that were invulnerable to German weapons.

The shells that bounced off the armor of the T34 were not a technical failure. They were the death nail of an entire military philosophy based on contempt for the enemy and the belief that the war would end before the bills had to be paid. However, the war did not end and the bill proved unaffordable.