1967, a Warner Brothers executive hung up the phone, hands shaking. Paul Newman had just said four words that could destroy a $6 million production. No Redford, no movie. The studio had refused to cast an unknown pretty boy from TV. They had better options, bigger names, safer choices. But what Newman did in the next 72 hours didn’t just save Robert Redford’s career.

It created one of the most legendary partnerships in Hollywood history. And it all started with a phone call nobody was supposed to hear. June 12th, 1967, Burbank, California. The Warner Brothers Executive Offic’s thirdf flooror corner suite. The air conditioning hummed against the summer heat, but the man behind the mahogany desk was sweating for a different reason.

Jack Warner, the studio head himself, had just finished reading William Goldman’s screenplay for a western called Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. It was perfect. A buddy film. Two outlaws on the run. Humor, action, heart, the kind of picture that could print money. There was just one problem. Paul Newman wanted Robert Redford.

Warner leaned back in his leather chair and lit a cigar. Robert Redford, a television actor. Decentl looking, sure, but television was where careers went to die, not where you found leading men for $6 million productions. They had better options. Warren Batty had expressed interest. Steve McQueen’s agent had called twice.

Even Marlon Brando, if they wanted to go that direction, these were names. These were guarantees. But Newman had been clear, crystal clear, almost maddeningly clear. I want Redford for Sundance. Warner picked up the phone. What he didn’t know was that this conversation would become Hollywood legend. The call where a studio head learned that sometimes the biggest star in the room isn’t the one behind the desk.

Paul Newman was 42 years old in 1967 at the absolute peak of his power. Cool hand Luke had just cemented him as more than a pretty face. He’d proven he could act, could carry a film, could open a movie nationwide. Studios needed him more than he needed them. But Newman had a problem that most movie stars didn’t have.

He actually cared about the work. He’d read Goldman’s script three times. The character of Butch Cassidy was perfect for him. Charming, funny, flawed. But the magic of the story was in the partnership. Butch and Sundance. Two men so in sync they finished each other’s sentences, trusted each other with their lives, made each other better.

You couldn’t fake that chemistry. You couldn’t manufacture it with whoever the studio wanted to cast. Newman had learned that lesson the hard way on previous films where he’d let the studio make decisions. This time would be different. He’d first worked with Robert Redford two years earlier in 1966 on a TV special.

Nothing major, but something had clicked. They had a rhythm, a natural ease. When Redford was on screen with him, Newman didn’t have to work as hard. The scenes just flowed. Redford was younger by seven years, hungry, still proving himself. But he had something Newman recognized because he’d once had it, too. That quality of not caring too much what people thought.

That outsider edge that made you interesting on screen. Warner’s voice came through the phone line, friendly but firm. Paul, let’s be reasonable about the Sundance casting. Newman stood in his Malibu kitchen, phone cord stretching across the counter. Through the window, the Pacific Ocean glittered in the afternoon sun.

I am being reasonable, Jack. I’m telling you who my co-star should be. Redford’s a television actor. So was Steve McQueen before you put him in The Great Escape. That was different. McQueen had presence. He had He had a good actor opposite him who made him look better, Newman interrupted. Which is exactly what I’m trying to set up here.

Warner’s tone shifted. The friendly studio chief disappeared. The businessman emerged. Paul, I’m going to be direct with you. We’re offering you Warren Batty. We’re offering you Steve McQueen. These are names that sell tickets. Redford is not. Newman’s jaw tightened. Then I’m offering you my exit from this project. Silence.

The kind of silence that costs millions of dollars. Warner cleared his throat. You’re under contract for three more pictures with us, Paul. For pictures I approve of, with casts I approve of. Check the contract, Jack. My lawyer made sure of that after the last disaster you put me in. Another silence. Then we’ll talk about this later, Paul.

When you’ve had time to think. I’ve had two years to think, Jack. My answer’s not changing. The line went dead. Newman set the phone down and poured himself a beer. His wife, Joanne Woodward, walked into the kitchen. She’d heard the whole conversation. You just threatened to walk away from the biggest western since the Magnificent 7, she said. I did.

They’re going to call your bluff. Then I’ll walk. Joanne studied her husband. After 12 years of marriage, she knew when he was posturing and when he was serious. This was serious. What is it about Redford? Newman took a long drink. You remember when we did the long hot summer? How you and I just clicked on screen? Of course.

That’s what happens with Redford. I don’t have to act as hard. I can just be and he matches me. That’s rare, Joanne. That’s worth fighting for. But what nobody in Hollywood knew was that Newman had another reason for wanting Redford. A reason he’d never told the studio. A reason that made this fight about more than just one movie.

Three years earlier in 1964, Newman had been at a party in Beverly Hills. Industry people, the usual crowd. He’d stepped outside for air and found a young actor sitting alone on the pool deck staring at the water. Robert Redford, 27 years old, recently arrived from New York Theater trying to break into film. They’d talked for two hours about acting, about the business, about how Hollywood chewed up talented people and spit them out as products.

Redford had said something that stuck with Newman. I don’t want to be a movie star. I want to be an actor who makes good movies. There’s a difference. Newman had felt the same way his entire career, but in 1964, he was already too deep into the star machinery to escape. Redford still had a chance, still had the opportunity to do it differently.

That’s when Newman made a private decision. If he ever got the chance to help Redford do it the right way, he would. Even if it meant fighting the studio, even if it meant risking his own career. Butch Cassidy was that chance. The next morning, June 13th, Newman received a call from his agent, Freddy Fields.

Warner Brothers had made their move. “They want to meet with you today, 3:00.” “What’s their play?” Newman asked. “They’re bringing in George Roy Hill,” Newman smiled. Hill was directing Butch Cassidy. “Smart move by the studio.” “Make the director talk sense into the stubborn star. Tell them I’ll be there.” That afternoon, Newman drove his Porsche through the Warner Brothers gates.

The guard waved him through without stopping. After 20 years in the business, Newman knew these lots better than his own neighborhood. The meeting was in the executive conference room. Leather chairs, wood paneling, photographs of Warner classics lining the walls. Casablanca, Rebel Without a Cause, My Fair Lady. A reminder of the studio’s golden history.

a subtle pressure tactic. Jack Warner sat at the head of the table, George Roy Hill sat to his right, and across from them, an empty chair waiting for Newman. “Paul, thanks for coming,” Warner began. All warmth now. The hard edge from yesterday’s phone call was gone. This was the studio chief as diplomat.

Newman sat down. “Jack,” Hill nodded at him. The director was a practical man, not given to Hollywood dramatics. He’d been a Marine pilot in World War II in Korea. He had no patience for ego games. “Paul,” Hill said, getting straight to it. “I’ve screen tested Warren Batty for Sundance. He’s good. Really good.

I think you two would have strong chemistry.” Newman leaned back in his chair. “Did you test Redford?” Hill hesitated. “Not yet.” “Then how do you know Warren’s the better choice?” “Paul, be reasonable.” Warner jumped in. “Batty is proven he’s Bonnie and Clyde. He’s box office. Redford is the right actor for this role. Newman finished.

Warner’s friendly mask slipped. Paul, I’ve been making movies since before you were born. I know talent when I see it, and I know what sells tickets. They’re not always the same thing. Then explain Steve McQueen to me. Explain James Dean. You gambled on them when they were unknowns. Those were different circumstances.

How? We had insurance, supporting casts, budget controls. Warner’s voice hardened. We’re talking about a $6 million production here, Paul. That’s the entire annual budget of some studios. I can’t risk it on your hunch about a TV actor. Newman stood up. The room went still. Then you’re going to have to make this movie without me. Hill’s eyes widened.

Warner’s face flushed red. Paul, sit down. Let’s discuss this like professionals. I am being professional, Jack. I’m telling you what I need to do my job. You’re telling me you know better. One of us is wrong. Newman picked up his car keys from the table. I’m betting it’s not me. He walked toward the door. Warner’s voice stopped him.

You walk out of this room, Paul, and you’ll never work at Warner Brothers again. Newman turned. Jack, you’re going to make Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid with Robert Redford and me, or you’re going to shove the project because I promise you, if you make it with anyone else, I’ll make sure every journalist in this town knows you passed on the biggest hit of the decade because you were too stubborn to listen to your star.

The threat hung in the air like cigar smoke. Warner stood up slowly. Get out of my office. Newman left. The drive back to Malibu felt longer than usual. The Pacific Coast Highway stretched ahead, curves and cliffs and ocean views that usually calmed him. Today, Newman barely noticed. Had he just destroyed his career for Robert Redford? Possibly.

Was it worth it? Newman thought about that 1964 conversation by the pool. He thought about every time a studio had forced him into a bad movie with a bad cast because they knew better. He thought about the kind of actor he wanted to be versus the kind Hollywood wanted him to be. Yes, it was worth it. When he got home, Joanne was waiting.

Well, I walked out. She closed her eyes. Paul, I know they’ll bury you. You know that, right? Warner has enough power to make sure you never work again. Then I won’t work again. Newman headed to the kitchen and opened a beer. But I’ll sleep at night. The phone rang at 10:47 p.m.

Newman, half asleep on the couch, picked it up, expecting his agent with bad news. Instead, Paul, it’s George. George Roy Hill. Newman sat up. George, I screen tested Redford this afternoon after you left. Newman’s heart was pounding. And you’re right. He’s got it. That thing you can’t teach, that ease. When I put the script in his hands and asked him to read Sundance’s lines cold, it was like the character walked into the room.

Did you tell Jack? I’m in his office right now. He’s agreed to a chemistry test. You and Redford tomorrow. If it works, you’ve got your Sundance. And if it doesn’t, Hill’s voice was dry. Then you’ve committed career suicide over nothing. But somehow I don’t think that’s going to happen. June 14th, 1967. Warner Brothers Sound Stage 6. Robert Redford arrived at 8 a.m.

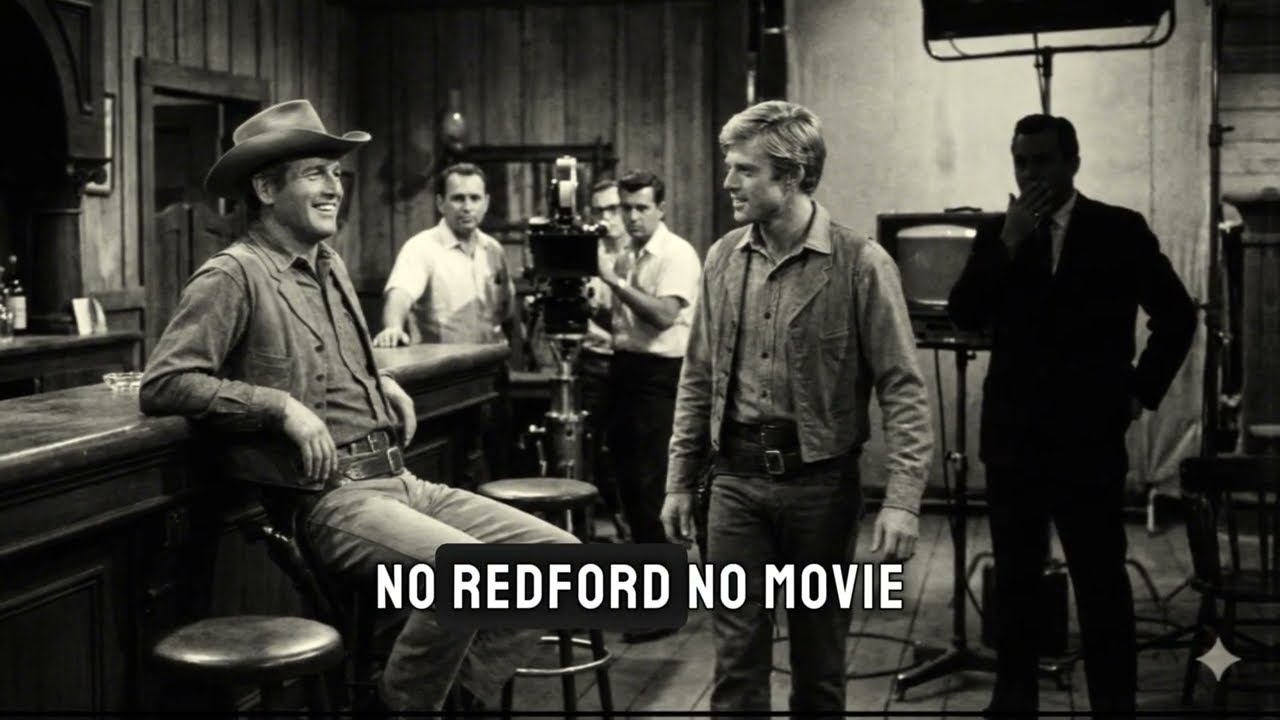

Not entirely sure why he’d been summoned for a screen test. His agent had been vague. Just show up, be yourself, and for God’s sake, don’t screw this up. He walked onto a western set. Minimal, a bar, some tables, the kind of place where outlaws drank and planned robberies. Paul Newman was already there, sitting at the bar in full costume.

He turned when Redford entered. Morning. Morning, Redford replied, suddenly aware this was more than a standard screen test. Paul Newman didn’t show up for those. Hill approached them. Gentlemen, I’m going to keep this simple. There’s a scene where Butch and Sundance rob a train. They’re waiting for it, sitting on a rock talking. Just talk. No script.

Improvise. Become these guys. Show me what you’ve got. For the next 20 minutes, Newman and Redford sat on that fake western set and talked. Not as actors performing lines. as Butch and Sundance, two outlaws who’d known each other so long they communicated in shorthand half sentences, knowing looks, the kind of friendship that didn’t need explanation.

Hill watched from behind the camera. Halfway through, he stopped giving direction. He just let them go. In the viewing room, Jack Warner sat in the dark, watching the screen, watching two actors who weren’t acting, who had found something real in the middle of a fake western town. When the test ended, Hill walked into the viewing room.

Well, Warner didn’t answer immediately. He was 75 years old, had been making movies for 45 years. He discovered Humphrey Bogart, James Dean, Doris Day. He knew Star Chemistry when he saw it. Get their contracts ready, he finally said. Redford Sundance. Hill smiled. You want to tell Paul or should I? You tell him and tell him he was right.

But off the record, Butch Cassidy and The Sundance Kid began filming in September 1967. From the first day, everyone on set knew they were watching something special. Newman and Redford had that rarest of Hollywood commodities, genuine friendship. They made each other laugh between takes. They challenged each other in scenes.

When one went big, the other went small. When one pulled back, the other filled the space. George Roy Hill directing them said later, “I didn’t have to create the relationship between Butch and Sundance. It already existed. I just had to point the camera at it.” But the real vindication came a year later. October 24th, 1969.

The film opened nationwide. The reviews were strong, but Hollywood insiders were skeptical. A western in 1969 when the genre was dying. First weekend box office, $5.2 $2 million. Second weekend, $6.1 million. It wasn’t just a hit, it was a phenomenon. By the time the dust settled, Butch Cassidy and The Sundance Kid had earned over $100 million domestically.

It became the highest grossing film of 1969. It received seven Academy Award nominations. It launched Robert Redford into superstardom. and it proved Paul Newman’s instincts had been worth fighting for. Years later, in a 1974 interview, Newman was asked about the Warner Brothers standoff. “Would you have really walked away from the film?” the journalist asked. Newman smiled.

“I didn’t think of it as walking away. I thought of it as walking toward the right choice.” “Sometimes those look the same.” Was Redford worth the risk? Bob wasn’t the risk. The risk was letting the studio make creative decisions they weren’t qualified to make. That’s what kills good movies. Executives choosing safety over truth, the journalist pressed.

But you could have lost everything. I could have, Newman agreed. But what’s the point of having power in this town if you don’t use it to make better work? I’d rather be unemployed and proud of my choices than rich and ashamed of my compromises. It’s a lesson Robert Redford never forgot. When he founded the Sundance Film Festival in 1985, it was built on the same principle Newman had fought for in 1967.

Trust the artist. Support the vision. Don’t let fear of risk kill something that could be extraordinary. Redford named the festival after the character that changed his life. The character Paul Newman fought for him to play. The character studio executive said he wasn’t ready for. Paul taught me that loyalty to the work matters more than loyalty to the system, Redford said in a 2002 documentary.

He put his career on the line for me when I was nobody. Not because he owed me something, but because he believed the movie would be better. That’s the kind of integrity Hollywood usually punishes. But once in a while, it rewards. The friendship between Newman and Redford lasted until Newman’s death in 2008.

They made three more films together. The Sting in 1973, which won seven Academy Awards, including best picture. Small appearances in each other’s projects. A lifetime of mutual respect. At Newman’s funeral, Redford spoke about that 1967 standoff with Warner Brothers. Paul never told me what he’d done until years later.

Never told me he’d threatened to walk. Never made me feel like I owed him something. That’s who he was. He fought battles for people and never asked for credit. Some people spend their lives becoming famous. Paul Newman spent his becoming free. Free from the studio system that wanted to control every decision. Free from the fear that saying no would end his career.

Free to choose his co-stars based on talent rather than box office insurance. That freedom cost him. He walked away from projects. He fought with executives. He made enemies in boardrooms across Hollywood. But it gave him something more valuable than any studio contract. It gave him the right to look in the mirror and know he’d made the best work he could with the people he believed in on his terms.

The phone call that saved Robert Redford’s career lasted four minutes. But the fight that led to it, that fight lasted 3 weeks. And the principle behind it that lasted a lifetime. Sometimes the biggest risk isn’t saying no to the people in power. It’s saying yes to the system that wants you to compromise. Paul Newman understood that.

And on June 12th, 1967, he drew a line. Hollywood’s been better for it ever since. What would you risk for the right choice? Not the safe choice, not the expected choice, the right one. Have you ever stood up for something you believed in, even when everyone told you it was career suicide? Share your story in the comments below.

If this untold story of loyalty and integrity moved you, hit that subscribe button for more Hollywood legends you’ve never heard. and share this with someone who needs to remember that sometimes the biggest wins come from the battles nobody saw you