June 1941, Halire Pass, Egypt, 11 km from the Libyan border. British tank crews called it Hellfire Pass, and they earned that name the hard way. Matilda tanks, the pride of British armor with 78 mm of frontal protection, advanced into what looked like empty desert. Then the first shell hit, one Matilda brewed up, then another, then another.

11 tanks destroyed in minutes, their armor punched clean through from over a kilometer away. The surviving crews who limped back to British lines had one question. What the hell just hit us? The answer was the German 88 mm flack gun, an anti-aircraft weapon that RML had dug into shallow pits behind sandbms, camouflaged and waiting for British armor to drive into his trap.

That gun would become the most feared weapon in North Africa. But here is what those tank crews did not know. Sitting in depot and airfields behind their own lines, the British had a gun that was actually bigger, actually more powerful, and actually capable of doing exactly what the 88 had just done to them. They had hundreds of them, and they were rarely authorized to use them against tanks. This is the story of the 3.

7 in anti-aircraft gun, the weapon that could have given RML’s tanks a taste of their own medicine, and the doctrinal rigidity that meant it almost never did. To understand why British tank crews died at Hellfire Pass, you need to understand what they were facing and what they had to fight back with.

By 1941, the Africa Corps had developed a devastating tactical system. German tanks would engage British armor, then feain retreat. British tanks would pursue, charging forward in the aggressive style their commanders preferred, and then they would drive straight into concealed 88 mm guns dug into the desert floor. The British two-pounder anti-tank gun, the standard weapon meant to stop enemy armor, could penetrate roughly 40 mm of steel at 1,000 m.

Against the newer German tanks with 60 mm of frontal armor, this was dangerously inadequate. Crews had to wait until panzas closed to point blank range before their shots had any chance of penetrating. By then, they were usually already dead. The mathematics of desert warfare were brutal. A German Panzer could engage a British tank at 1500 m with reasonable accuracy.

A British two-p pounder crew needed their target within 500 m to have any hope of a kill shot. That meant crossing a full kilometer of open ground under fire before being able to shoot back effectively. Tank commanders called it the killing ground, and crossing it cost the Eighth Army hundreds of vehicles and thousands of men.

The 88 mm flack firing its 9 kg shell at over 800 m/s could penetrate 105 mm at the same distance. It could kill a Matilda before the British crew even knew they were under fire. And RML had integrated these guns directly into his Panza formations. They moved with his tanks. They set up in minutes.

They created killing grounds that British armor stumbled into again and again. By late 1941, contemporary accounts credit just two Luftwaffer Flack battalions operating in North Africa with destroying over 200 tanks and dozens of aircraft. The exact totals are disputed by historians, but even conservative estimates show an astonishing kill ratio.

A relatively small number of 88s achieved outsized results, and British commanders had no effective counter. What the British needed was a weapon that could match this capability. A gun that could reach out and kill German armor at long range before panzas could close to effective distance. A gun that could turn the tables and make German tank commanders fear the open desert the way British crews had learned to, they already had one. It was called the QF 3.

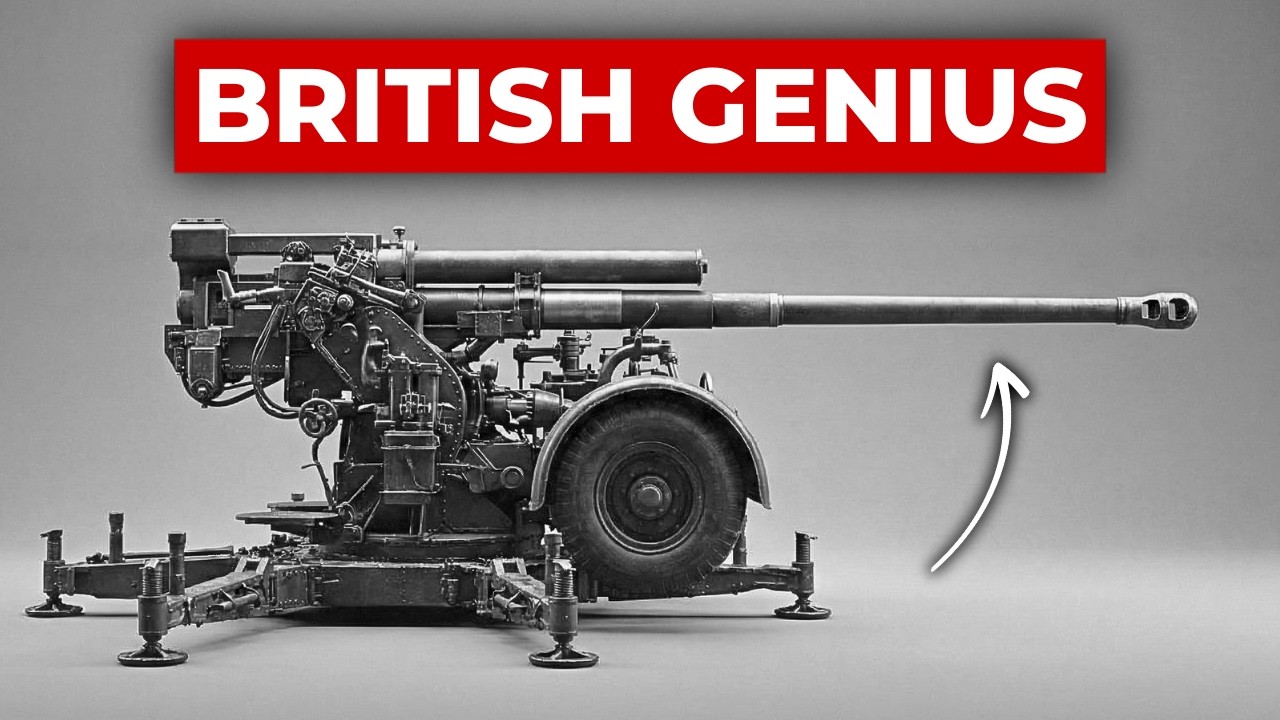

7 in anti-aircraft gun. And by every meaningful ballistic measure, it was superior to the weapon that was slaughtering British tank crews. The 3.7 in gun emerged from a 1933 specification that demanded a weapon capable of engaging aircraft at 35,000 ft. Vicers Armstrongs delivered a design that would serve Britain for nearly 20 years from 1938 until guided missiles replaced it in 1957.

The numbers tell the story of its potential. The bore measured 94 mm, 6 mm larger than the German 88. The shell weighed 12.7 kg, nearly 40% heavier than what the 88 fired. Muzzle velocity reached 792 m/s. And when fitted with armor-piercing ammunition, the 3.7 had theoretical anti-tank performance comparable to heavy guns of its class, capable of defeating any German tank then in service at combat ranges.

The rate of fire matched or exceeded the German weapon at 8 to 10 rounds per minute with handloading. By 1942, the introduction of the Mullins’s automatic fuse setter pushed this to 20 to 25 rounds per minute for anti-aircraft work. The gun offered 360 degree traverse and could depress to -5° for ground engagement, though this required the full platform setup.

A later variant, the Mark 6, introduced in 1943, extended barrel length to 65 calibers and achieved a muzzle velocity of over a,000 m/s with an effective ceiling of 45,000 ft. It became one of the finest heavy anti-aircraft weapons produced by any nation during the war. Production had ramped up urgently as war approached.

Britain had only 180 heavy anti-aircraft guns in January 1938. By the declaration of war in September 1939, 540 guns defended British airspace. During the Battle of Britain, 1140 heavy anti-aircraft guns were in service. By wars end, total production across facilities in Britain, Australia, and Canada would reach into the thousands. The capability existed.

The weapons existed in growing numbers. The ammunition existed, including purpose-built armor-piercing rounds. Yet, those guns sat protecting airfields and rear area installations. while tank crews burned. The reasons were partly technical and partly institutional, and the institutional failures were worse. The 3.

7 in gun weighed 9,300 kg in its mobile configuration, nearly 2 tons heavier than the German 88, it stood over 3 m tall when traveling, presenting an enormous target that was almost impossible to conceal in the flat desert. Deployment time stretched to 15 minutes with a well- drilled crew. The German 88 could be firing in 2 and 1/2 minutes.

The carriage created additional problems. Designed for high angle anti-aircraft fire with radar directed predictors, it lacked the lowprofile deployment capability that made the German gun so effective. The 88 could fire from its traveling bogeies using simple outriggers. The 3.7 required complete setup on its crucifform platform.

Veterans reported that the guns disliked being fired horizontally and that recoil springs broke frequently when engaging ground targets. Perhaps most critically, no optical direct fire sight was provided as standard. The gun was designed to be aimed by mechanical predictors calculating lead angles against aircraft.

Field modifications called Dorbrook sites attempted to graft anti-tank telescopes onto the mount, but crews described them as inadequate for the task. These were real limitations, but they were not insurmountable. The Germans had faced similar challenges with the 88 and solved them through pre-war planning and tactical adaptation.

The British had the engineering capability to develop proper ground fire sights, lighter mountings, and faster deployment procedures. They simply never prioritized it. Now, before we examine how this gun actually performed when it was used against tanks, if you are finding this interesting, consider subscribing. It helps the channel more than you might think and takes just a second.

Now, back to the desert. The deeper failure was organizational. In Britain, heavy anti-aircraft guns belong to anti-aircraft command, which from April 1939 operated under RAF fighter command for home air defense. This created a model where anti-aircraft assets served air priorities first. In the Middle East, heavy anti-aircraft regiments followed a similar logic, deploying at core and army level to defend ports, airfields, and logistic centers rather than attaching to divisions where anti-tank capability was desperately

needed. The command structure created perverse incentives. Anti-aircraft command measured success by aircraft shot down and installations protected not by tanks destroyed or armored operation supported. Releasing guns from air defense to support ground combat meant accepting risk to the airfields that kept the desert air force operational.

Commanders who had watched the Luftwuffer devastate undefended positions were understandably reluctant to strip away their air protection even when tank crews were dying for want of heavy guns. There was also the question of ammunition supply. Anti-aircraft batteries consumed enormous quantities of high explosive shells engaging aircraft.

Introducing armor-piercing rounds into the logistics chain meant competing priorities, separate supply lines, and the risk that guns might run short of the ammunition they needed for their primary mission. These were real concerns, though they could have been solved with adequate planning. The contrast with German practice could not have been starker.

The Germans deliberately stocked armor-piercing ammunition for dual roll use, something British anti-aircraft logistics did not prioritize early in the war. This was pre-planned capability developed from experience in the Spanish Civil War. From 1936 to 1939, four batteries of Flak 18 guns deployed with the Condor Legion and engaged in 377 combat actions.

Only 31 of those were against aircraft. The rest targeted tanks, bunkers, and ground fortifications. German commanders learned in Spain that their anti-aircraft guns were devastating tank killers, and they built that lesson into their doctrine before the war even began. RML understood this personally. At the Battle of Ars in May 1940, British Matilda tanks attacked his 7th Panza division.

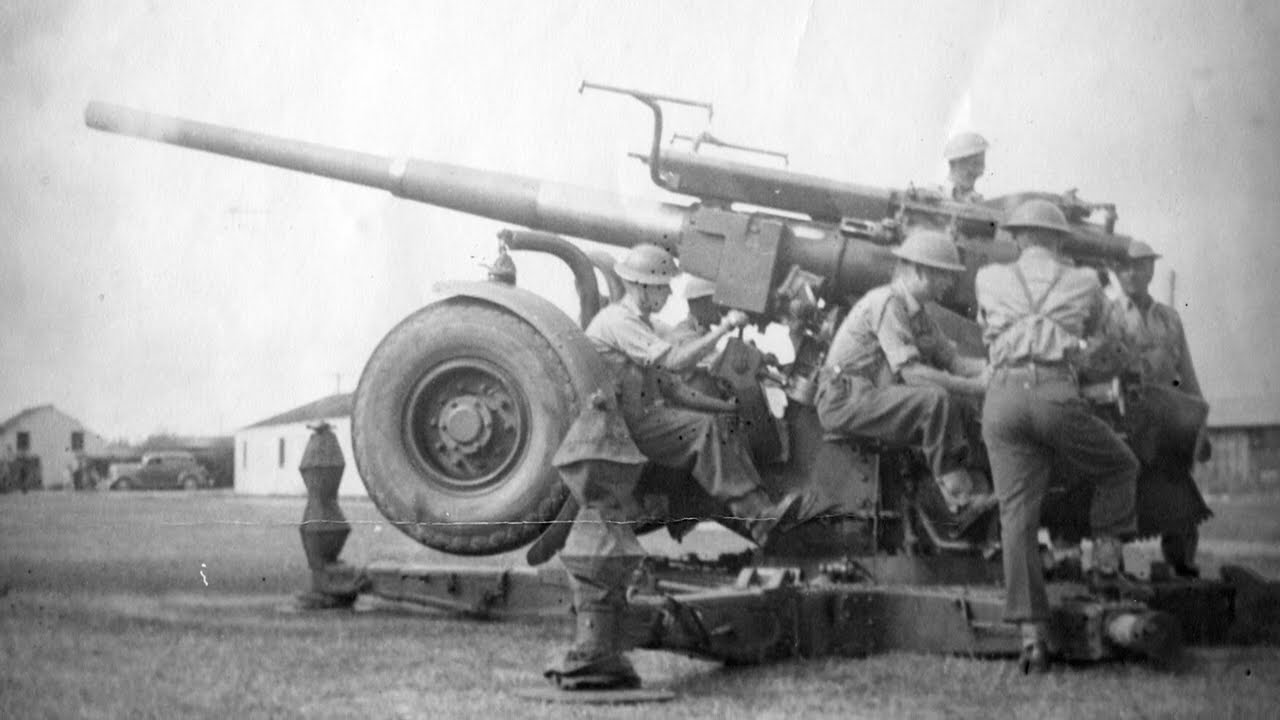

German 37 mm anti-tank guns bounced harmlessly off the Matilda’s thick armor. RML personally organized a gun line of 105 mm howitzers and 88 mm flat guns. He stopped the attack. He remembered that lesson when he reached Africa. Despite institutional resistance, the 3.7 in was employed against ground targets on documented occasions.

The siege of Doughbrook from April to December 1941 saw the most extensive use. The 51st London Heavy Anti-aircraft Regiment, equipped with 24 guns, engaged ground targets, including German airfields when enemy aircraft landed, conducted counter battery fire against Axis artillery at ranges beyond what normal field guns could reach, and delivered night harassing fire on roads.

The 94th Heavy Anti-aircraft Regiment spent four years in the desert, and Unit War diaries document multiple instances of ground target engagement. In September 1942, practice firing against ground targets was observed by General Alexander himself alongside Brigadier Calbertt Jones. The brass knew the capability existed.

They watched it demonstrated and still they did not change policy. An eighth army lessons learned document confirmed the results. Very effective. The guns were very accurate and fragmentation was excellent. But this was improvised local employment, not systematic doctrine. At Elam in June 1942, after the disaster at Gazala, Brigadier Dennis Reed authorized anti-aircraft guns to engage attacking armor.

Approximately 200 rounds were fired in a single day. The result was striking. German tank commanders refused to press their attack and sought an easier target elsewhere. The 3.7 had demonstrated exactly the capability that British tank crews had been begging for. Yet, even this success did not change policy.

It bears emphasizing that the guns which earned Hellfire past its Hellfire nickname were German 88s, not British 3.7s. On June 15th, 1941, during Operation Battle Ax, Captain Wilhelm Bach positioned five concealed 88 mm guns overlooking the pass. British Matildas advanced into his killing ground. 11 to 15 tanks were destroyed in the ambush.

The name Hellfire Pass commemorates a German victory achieved with German weapons. No evidence suggests British 3.7in guns were present at that engagement. The British had the capability to create their own hellfire pass. They simply never deployed it. The popular narrative holds that stupid generals ignored a perfect weapon while tank crews died.

The reality requires more nuance, though that nuance does not excuse the failure. To be fair to the decision makers, heavy anti-aircraft guns were not sitting idle. They defended the airfields that kept the desert air force operational, the ports that sustained supply lines, and the logistics dumps that fed the entire campaign.

Stripping away the protection meant accepting risk that Axis bombers could British operations from the air. The 3.7 was also genuinely harder to conceal in flat desert, slower to imp place under fire, and lacked purpose built direct fire sites early in the war. These were real constraints, not excuses invented after the fact. But constraints can be overcome when the will exists.

The Germans face similar problems and solved them. Lieutenant David Perry of the 57th Light Anti-aircraft Regiment provided the most quoted criticism, claiming over a thousand 3.7in guns stood idle in the Middle East and that many never fired a shot in anger during the whole war. He condemned the sheer stupidity of the general staff.

This account, emotionally powerful as it is, oversimplifies genuine technical constraints. Historians Shelfford Bidwell and Dominic Graham acknowledged the controversy in their authoritative work firepower. They added bitingly that even if the guns had been made available, it was doubtful the desert commanders would have used them correctly given the hash they made of employing all their own artillery.

Advocates for change did exist within the British system. Brigadier Percy Calvert, commanding fourth heavy anti-aircraft brigade, reportedly solved the theoretical deployment problems by summer 1942. Field Marshall Alan Brookke as commander home forces in 1941 tested 3.

7in anti-tank capabilities against the possibility of German invasion. The 103rd heavy anti-aircraft regiment was assigned a secondary anti-tank role in case German heavy tanks landed in Britain. A plan even existed to mount heavy anti-aircraft derived guns onto armored chassis. It was abandoned when the Royal Artillery and the Royal Armored Corps could not agree on which branch would own the resulting vehicles.

That single bureaucratic dispute encapsulates the entire failure. The British ultimately solved their anti-tank problem with purpose-built weapons rather than adapted anti-aircraft guns. The six pounder arrived in spring 1942, penetrating 74 mm at 1,000 m. The 17 pounder from 1943 achieved 130 mm with standard ammunition and 192 with discarding Sabbat rounds.

These were excellent weapons, but they arrived too late for the tank crews who faced the 88 with only two pounders for protection. During the critical 18 months when British armor suffered its worst losses, the 3.7 offered an existing solution that institutional barriers prevented from being exploited. After Normandy, the British finally employed 3.

7 in guns extensively in ground rolls, though primarily against fortifications rather than tanks. The 60th Heavy Anti-aircraft Regiment fired 2,450 rounds in ground roll during the Normandy campaign, increasing to 25,000 by October 1944. The weapon became valued as a concrete buster for destroying bunkers and strong points. Low-angle range tables were officially issued in May 1942, a belated institutional acknowledgement that ground engagement was possible.

The Ordinance QF 32 pounder developed directly from the 3.7 in design was created specifically as a heavy anti-tank weapon capable of penetrating 228 mm with discarding Sabba ammunition. Development halted when the war ended. The Germans valued captured 3.7 in guns enough to designate them 94 mm flak vicers M39E and manufacture ammunition specifically for their use.

That designation tells you everything about the weapon’s quality. The enemy recognized what British commanders refused to exploit. The 3.7 in anti-aircraft gun stood in British service until 1957. 45 guns reportedly remain in service with Nepal to this day, nearly 90 years after the design process began. It was one of the finest heavy anti-aircraft weapons of the Second World War.

capable of engaging aircraft at altitudes no German bomber could safely fly and capable of destroying any tank the Vermack fielded that it rarely did the latter was not a failure of engineering. British designers created a weapon that exceeded German specifications in almost every meaningful way. It was a failure of doctrine, of organization, and of institutional flexibility.

The Germans did not improvise 88 mm anti-tank tactics in the heat of battle. They developed them deliberately in Spain years before the desert fighting began. They built dual roll capability into their logistics, their training, and their command structures. When RML needed tank killing guns, they were there because someone had planned for them to be there.

The British built a superior gun and then built walls between the people who had it and the people who needed it. When tank crews burned at Halire Pass, when Matildas brewed up across the desert, when the 88 earned its fearsome reputation, those crews did not know that bigger, more powerful guns sat behind their own lines, pointed at the sky, waiting for aircraft that often never came.

As one contemporary document noted with tragic irony, during this period, the Allied forces had over three times as many 3.7in guns available as the Axis forces had 88s. Yet, German and Italian tank crews probably never even got to see one. The 3.7 in anti-aircraft gun proves that having superior technology means nothing without the doctrine to employ it.

It would not have been a magic wand, but it could have saved crews and bought time during the desperate months when the two pounder gap left British armor vulnerable. British engineering excellence created a weapon with genuine potential. British institutional rigidity ensured that potential was never fully exploited. The tank crews who burned at Hellfire deserved better.