In the fall of 1941, the Red Army received weapons that could not be dropped, stored near a fire, or used in freezing temperatures. Its shells were made of glass. Its barrel was a piece of water pipe. Inside the glass spheres, there was a liquid that ignited on its own, burned at 1,000°, and could not be extinguished with water.

The gunners went into battle with buckets of copper sulfate because it was the only means of salvation if the shell burst in the barrel and turned you into a living torch. It was an attempt to stop an army that had marched from Warsaw to Paris and from Paris to Moscow in 2 years with the help of Napal in glass balls. This is a story about how they tried to make artillery out of water pipes and bottles and about the price paid by those who held this weapon in their hands.

But the strangest thing was something else. The Soviet Union was not alone in this madness. At the same time, on the other side of Europe, another great power came up with the same idea. In the summer of 1941, two countries at opposite ends of Europe simultaneously reached the same decision.

Both had lost most of their anti-tank weapons. Both faced the threat of tank breakthroughs that could not be stopped, and both began stuffing bottles of flammable mixture into metal pipes, hoping that it would work. In Britain after the evacuation from Dunkirk, there were 167 anti-tank guns left in the whole country. 840 guns were abandoned on the French beaches along with thousands of trucks and tanks.

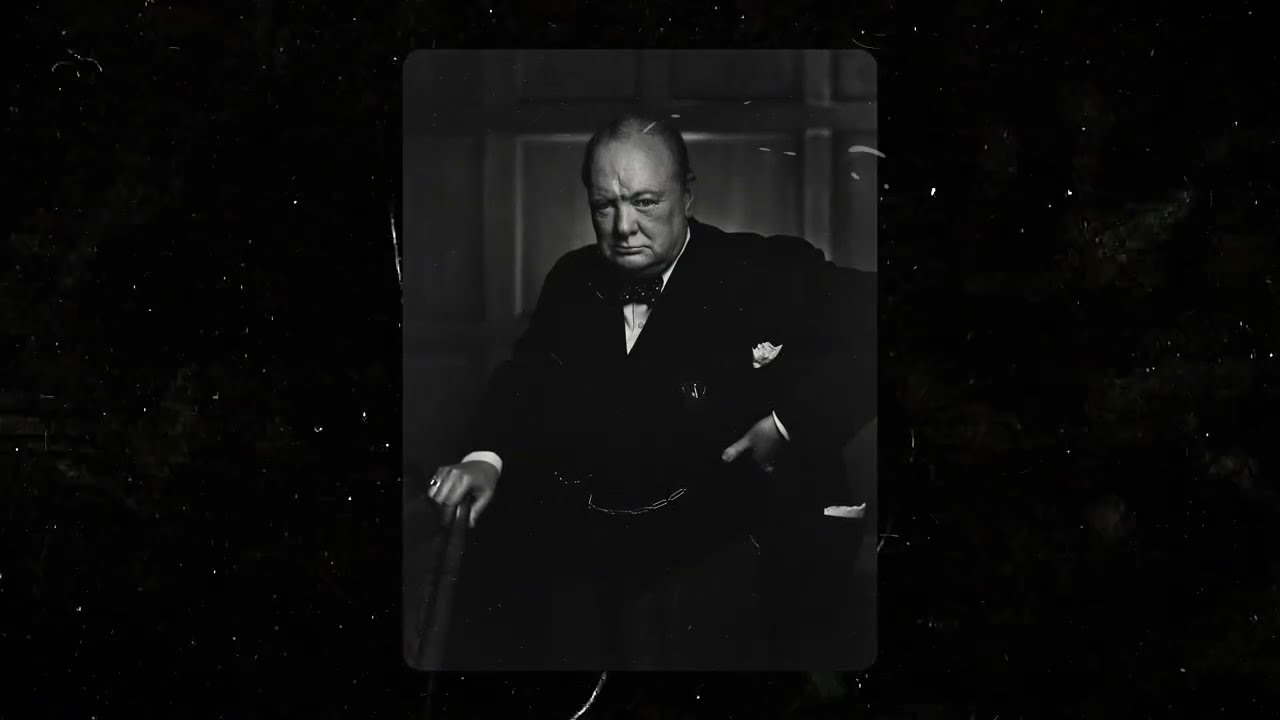

The German invasion was imminent. Major Robert Nordtover of the Home Guard proposed his solution. A smooth boore pipe on a tripod loaded with black powder and firing bottles of phosphorus mixture. The cost was £10 per unit, excluding the tripod. Winston Churchill personally attended the demonstration, approved the project, and ordered the production of 18,000 such devices.

The prime minister of the world’s greatest colonial empire, watched as bottles of incendiary mixture flew out of the pipe, and saw in this a salvation. The situation in the Soviet Union was no better. The cauldrons near Kiev, Basma, and Brians swallowed up hundreds of thousands of soldiers along with their weapons.

The infantry left without artillery was attacked by tank columns that had practiced blitzkrieg in Poland, France, Greece, and Yugoslavia. Two years of continuous victories against water pipes and glass balls. Degario’s anti-tank rifles were just beginning to be supplied to the troops. An RPG 40 grenades required the soldier to get close enough to the tank to throw the grenade and still remain alive.

And then from the arsenals of the aviation industry, they took out a development that was initially intended for entirely different purposes. And then someone remembered a development that was gathering dust in the archives of an aircraft factory. It was intended for bombers, but now they were going to give it to the infantry.

The problem was not only a shortage of weapons. The problem was that the remaining means of fighting tanks required almost suicidal bravery from the infantry man. A bottle with an incendiary mixture flew 30 m if thrown from a running start. An RPG 40 grenade weighing more than a kilogram flew even closer.

An anti-tank rifle could pierce armor, but a twoman crew with a long, clumsy design became a priority target for German machine gunners. And the tanks came in waves. After breaking through the front line, mechanized columns wedged themselves dozens of kilometers deep into the Soviet defenses, and the infantry that found themselves in their path often had nothing heavier than a rifle.

In this situation, any weapon capable of setting a tank on fire from at least 100 m seemed like a lifesaver, even if that weapon was made from a water pipe and fired glass balls. There was a designer working in the USSR who had been recommended by Illusian and Tupalev themselves. He was tasked with creating a weapon from a water pipe and a hunting cartridge.

At the Kiraov plant in Moscow, which was part of the people’s commissarat of aviation industry, chief designer Ivan Kartukov was engaged in specific developments. From the age of 11, he worked as a mechanics assistant at a shell factory in Oro, then volunteered for the Red Army, and then studied and built a career as an engineer.

By the beginning of the war, Cartikov was designing aircraft devices for spraying chemicals from aircraft, cassettes for small bombs, and glass spheres with self-igniting liquid for striking ground targets. He was recommended for the position of chief designer by Illusian and Tupalev themselves. He received his candidate of sciences degree by personal decree of Stalin without defending a dissertation as one of 25 leading specialists in Soviet aviation.

The AK-1 glass ampools 125 mm in diameter with 10 mm thick walls were initially intended fordropping from bombers. Inside 2 L of KS liquid slloshed around. There were several interpretations of this abbreviation. Koskin’s mixture after the inventor’s surname, old cognac in soldier slang, and top secret in engineers jokes. The composition was no joke.

White phosphorus dissolved in carbon dissolvide. Upon contact with air, the liquid ignited instantly. It burned for about 3 minutes at temperatures up to 1,000°. It could only be extinguished with sand or a solution of copper sulfate. Water did not help. When it came into contact with skin, the phosphorus continued to burn, scorching the tissue down to the bone.

And the only way to stop it was to cut off the burning flesh with a knife. Now they have decided to adapt these aviation munitions for infantry use. The barrel of the ampule launcher was a solid steel tube with a wall thickness of 2 mm. Inside, closer to the brereech, a lattice splitter was installed to protect the fragile ampool from the impact of powder gases when fired.

A standard 12- gauge hunting cartridge served as the propellant charge. A hunting cartridge against tanks that was the essence of 1941. After military trials, the ampule launcher was officially adopted for service. It was no longer an experiment by a few enthusiasts, but a systematic solution. The state defense committee issued decrees on the production of ampool launchers and ammunition for them.

An ampool launcher platoon of four guns appeared in the rifle regiment. Separate ampool launcher teams and companies were formed. Lennengrad, cut off from supplies during the blockade, began to produce Ampool launchers on its own. The barrels were cut from water pipes and the mounts were welded from whatever was available.

The weight of the finished product ranged from 10 to 28 kg depending on where and from what it was assembled. The crew consisted of three people, a gunner, a loader, and an ammunition carrier. Each crew had to carry a bucket of copper sulfate solution in case of an emergency fire. This bucket was as essential a piece of equipment as the pipe and glass balls themselves.

The ampules were filled with KS liquid at special field stations in the frontline zone. It was impossible to store them filled for long. Transporting them was dangerous and dropping them was strictly forbidden. But there was no turning back. Thousands of ampule launchers went to the front along with thousands of fragile glass spheres filled with a substance that did not forgive mistakes.

There were places and moments when this strange weapon really worked. Near Sevastapole in 1941, a German pillbox defended its sector so skillfully that the Marines could not get close to it. The plan was rehearsed to perfection. The Germans let the attackers get within 10 paces, fired a blue signal rocket from the embraasure, and immediately began firing mortars at the attackers.

The scouts suffered losses again and again. Then the head of the brigade’s chemical service, Captain Bdanov, suggested using ampule launchers. After several attempts, one of the soldiers managed to hit the embraasure directly with an ampool. The German garrison rushed out as if scalded, choking on the phosphorous smoke, and the pillbox was taken.

On the Curelian front, Ampool launchers found their tactical niche within the so-called nomadic groups. one or two ample launchers, several snipers, a machine gun, and a support weapon. At night, the group secretly advanced to a position in the neutral zone. At dawn, they fired several volleys at the Finnish fortifications.

They immediately withdrew under the cover of darkness before the enemy could organize a counterattack. It was a mosquito bite tactic. Strike and disappear. In five months, one such group destroyed 17 pill boxes and three tanks and started 21 large forest fires on enemy territory. In July 1942, an ampule grenade squad fired on the town of Povvenets from a distance of just over 100 m.

The city burned for 2 days in Stalenrad, where battles were fought for every basement and every stairwell. Ampule launchers found their place in assault groups. At a distance of 50 m when the enemy was holed up in the house opposite and needed to be smoked out, a glass ball with napal worked no worse than artillery. Fire did what bullets could not.

It forced the enemy to leave their cover or burn alive. Sevastapole, Carellia, Stalenrad, these were islands of success in an ocean of disaster. And one general decided to find out why. In the winter of 1941, 20 new ampule launchers were delivered to the Western Front for demonstration to the command.

Major General Leoshenko, the commander of the army, came to the test himself. He was not a desk general, but a combat officer with an unquestionable reputation. During the Finnish War, he stormed the Manahheim line and received his first hero star. In the fall of 1941, his brigade stopped Gdderian’s tank group near Matsensk, one of thefew successes in those terrible months.

The soldiers called him general forward for his speed and drive. When such a man passes judgment on a weapon, that judgment is final. The designer began to explain the loading procedure. Leoshenko listened, frowned, and grumbled that it was too complicated and timeconuming, and that the German tank would not wait.

With the first shot, the ampule shattered right in the barrel, and the ampule launcher turned into a torch. The general demanded a second one. History repeated itself. Leusenko cursed, forbade his soldiers from using this weapon, and ordered the remaining Ampool launchers to be crushed by a tank. The man who had stopped Gderion was not going to send his soldiers into battle with weapons that killed them.

But Leusenko was not alone. Another division conducted training exercises and compiled a report. Of 52 ampools, 19 exploded in the barrel. 36% were defective. Of the 12 ampools that did reach their target and break, eight did not ignite at all. The reason lay in the very nature of the ammunition.

The glass spheres were both too fragile to be fired and too strong to hit soft targets. They cracked from the impact of the powder gases when they left the barrel, but did not break when they fell into loose snow or marshy ground. There was another even more serious problem. Some of the ampules were initially designed to be dropped from aircraft and were equipped with contact fuses.

Outwardly, they were almost indistinguishable from ordinary mortar ampools. When such ammunition accidentally fell into the hands of the infantry, it detonated in the barrel and there was nothing left to extinguish the fire. By the end of 1942, Ampool launchers were removed from service.

By this time, regular anti-tank guns and artillery had finally reached the front. The need for glass artillery had disappeared. A strange fate awaited the ampule launcher after its official demise. The weapon itself disappeared from the combat units inventories. Still, the ampules were used in aviation until the very end of the war.

Attack aircraft dropped them on enemy columns and fortifications and there in the air. The fragility of glass was not a disadvantage, but an advantage. Ample launchers found an unexpected use in the troops. Political officers discovered that this tube was very convenient for throwing bundles of propaganda leaflets into German trenches.

A weapon designed to burn the enemy alive became a tool of propaganda. According to some sources, ampool launchers were used in this capacity until the very end of the war, even in 1945. On the other side of the English Channel, the British Nortonwearer grenade launcher never fired a single shot in combat.

The German invasion did not take place, and the 18,000 bottle mortars that were produced remained a monument to an era of despair. British militia men nicknamed their weapon the bottle mortar. They treated it with the same dark humor that Soviet soldiers treated the Ampool launcher. But the idea did not die.

Seamian Federos, a journalist for the military industrial courier, noted that the principles behind the Soviet ampool launcher were developed further in post-war capsule flamethrowers. The concept of throwing an incendiary capsule at a distance beyond the reach of a backpack flamethrower proved viable. It was simply put into practice in 1941 using whatever was at hand.

Today, these strange weapons can be seen in several museums. In the state memorial museum of the defense and siege of Lenenrad, there is an ampule launcher next to a glass sphere. There is another example in the Stalenrad battle panorama museum. Visitors walk past without understanding what they are looking at. These pipes do not look like weapons.

They look like plumbing fixtures that someone mistakenly put on display. The ampule launcher was not a mistake made by untalented designers. After the war, Ivan Cardikov continued his career and became a laurate of the Stalin, Lenin, and state prizes. The design bureau he headed was later named after him.

They look like plumbing fixtures that someone mistakenly put on display. The ampule launcher was not a mistake made by untalented designers. After the war, Ivan Cardikov continued his career and became a laurate of the Stalin, Lenin, and state prizes. The design bureau he headed was later named after him.

He worked on systems for spacecraft. He was a man recommended by Illusian and Tupalev, not an amateur who happened to find himself at the drawing board, but one of the best engineers of his generation. It’s just that in 1941, he was ordered to do the impossible, and he did what he could. The ampule launcher was a symptom of disaster.

It appeared because in the summer and fall of 1941, the Red Army lost most of its anti-tank weapons. This was because the factories had been evacuated to the east and had not yet begun production. Because tank columns were pushing deep into the country and the infantry had nothing to stop them.

In such a situation, even glass balls filled with napal seemed like a solution. The same thing happened in Britain after Dunkirk. The same thing happens everywhere where war catches acountry unprepared. People grab whatever means are at hand, invent weapons from what they have, and go into battle with these weapons. Sometimes it works.

More often it kills those who were supposed to destroy the enemy. The soldiers who carried glass spheres and a bucket of copper sulfate into battle were not fools, nor were they suicide volunteers. They were people whom their country sent to fight with what it could give them. And they fought.

They set fire to pill boxes near Sevastapole. They set forest fires on the Curelian istmas. They smoked the Germans out of the basement of Stalenrad. They paid for it with burns, injuries, and lives. The ampial launcher remained in service for less than two years, during which time, those were the most terrible two years of that war.

Then came standard weapons. Then came victory, then came oblivion. Glass artillery was removed from the textbooks because it was an uncomfortable reminder of how it all began. Of the price of unpreparedness for war, paid not by generals or designers, but by those who hold weapons in their hands.