At 6:00 a.m. on the morning of November 18th, 1944, Corporal Harlon Vance crouched in a hole full of freezing water, watching a patch of gray fog 40 yards to his front. He was stuck in the Huichin forest, a 50s square mile patch of hell on the German Belgian border that the soldiers simply called the death factory.

To his left, a 19-year-old private from Ohio was shivering so violently that his dog tags were rattling against his collar. To his right, the body of their sergeant lay covered by a poncho, stiffening in the cold. The temperature was 33°, just warm enough to rain, just cold enough to freeze that rain into a layer of ice on every rifle bolt, helmet, and tree branch in the sector.

The Huichin wasn’t like the open fields of France or the beaches of Normandy. It was a claustrophobic nightmare where the sun never seemed to touch the ground. The pine trees grew so thick you couldn’t see 20 ft in front of your face. It was like fighting inside a dark closet filled with razor blades.

The Germans had been living in these woods for months. They had pre-registered their artillery on every trail, every clearing, and every foxhole. When their shells hit the canopy, they didn’t just explode in the dirt. They detonated 50 ft in the air, shattering the massive pine trees, and sending wood splinters the size of steak knives raining down on the men below.

You couldn’t dig a foxhole deep enough to hide from a tree burst. Vance watched the fog. He knew the Germans were out there, specifically the 275th Infantry Division, hardened veterans who knew every route and rock in this forest. They were waiting for the Americans to make a mistake, and the Americans were making plenty.

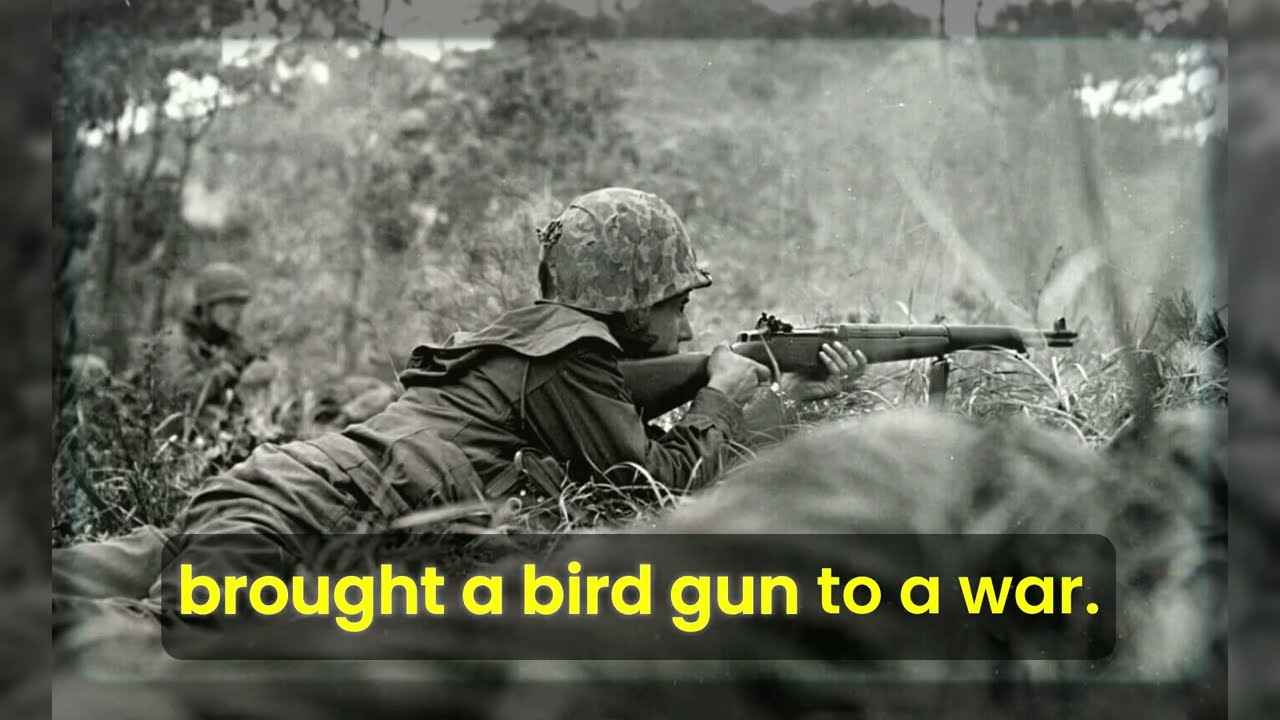

The biggest problem wasn’t courage, it was equipment. The standard issue US infantry rifle, the M1 Garand, was the best battle implement ever devised. It was semi-automatic, accurate, and powerful. But in the dense tangle of the huichin, the garand was a liability. It was 43 in long and weighed nearly 10 lb.

Trying to swing a garand around in that thick brush was like trying to swing a baseball bat in a phone booth. By the time you got the barrel leveled, the German with the short MP40 submachine gun had already put three rounds in your chest. But Harlon Vance wasn’t carrying a garand. Resting on his knees, keeping the mud out of the action, was a weapon that looked like it belonged in a museum or a pawn shop.

It was a Winchester Model 1897, a 12- gauge pumpaction shotgun with an exposed hammer that looked like a spur on a cowboy’s boot. It was ugly, heavy, and loud. The bluing on the steel was worn down to silver, and the walnut stock was scratched from years of use. It wasn’t a military weapon. It was a riot gun, a trench sweeper, a relic from the First World War that the army had largely phased out in favor of submachine guns.

Vance’s commanding officer, Lieutenant Miller, hated the thing. 3 days earlier, when the platoon was gearing up at the depot near Rot, Miller had stopped in front of Vance and pointed at the shotgun with a look of pure disgust. He asked if Vance was planning to go duck hunting or if he intended to actually fight a war. The rest of the squad laughed.

It was the kind of nervous, mean-spirited laughter you hear when men are scared and looking for someone to pick on to relieve the tension. They called Vance Birdie. It started as a joke about his name, but it turned into a dig at his weapon. They asked him if he brought any bird seed. They asked him if he needed a retriever dog to fetch the Germans after he shot them.

The mockery didn’t stop with the jokes. The platoon armorer had actually tried to confiscate the weapon. He argued that the Model 97 was a logistical nightmare. The issue wasn’t the gun itself. It was the ammunition. In 1944, shotgun shells were made of paper, not plastic. The armorer explained slowly and condescendingly that in the humidity of the Huichin forest, those paper hulls would absorb moisture from the air.

They would swell up like a wet sponge. When you tried to pump a swollen shell into the chamber, it would jam. And when you have a jammed weapon 40 yard from a German machine gun nest, you are a dead man. The armorer told Vance to be smart, drop the toy, and pick up a Thompson submachine gun like a professional. Vance had refused. He didn’t say much.

He was a man of few words, the kind of guy who listened more than he spoke. He just held on to the Winchester and told the lieutenant that he’d take his chances. What he didn’t explain to them because they wouldn’t have understood was that he wasn’t relying on the weapons specs. He was relying on geometry.

Vance had grown up in the backwoods of Kentucky. He had been shooting since he was big enough to hold a stock against his shoulder. He wasn’t just a hunter. He was a natural pointer. In 1938, he had won a regional ski championship by hitting 100 straight clays without a miss. He understood light, spread, and timing in a way that couldn’t be taught in basic training.

He knew something about the Huichin forest that the officers with their maps and compasses were missing. This wasn’t a war of precision. This was a war of reaction time. The Germans weren’t standing in open fields at 300 yd. They were popping up from spider holes 10 ft away.

They were charging out of the mist, screaming. In that split second, you didn’t have time to align the iron sights of a rifle. You didn’t have time to find a sight picture. You needed to point and delete. You needed a wall of lead that moved faster than the enemy could think. The Thompson submachine gun was fast, sure, but it fired pistol rounds.

A 12- gauge shell loaded with doubleot buckshot through threw nine lead pellets, each the size of a 32 caliber bullet, all at once. It was like firing nine pistols simultaneously with a single pull of the trigger. The lieutenant had walked away shaking his head, writing Vance off as a hillbilly who would be dead within the week. The squad leaders put Vance on point during patrols, figuring he was expendable.

If Birdie wanted to play hunter, he could flush out the enemy for the real soldiers. For 3 days, Vance had taken the insults. He had listened to the Snickers every time he cleaned the mud off his fouling peace. He watched the other men oiling their high-tech semi-automatic rifles and their grease guns, secure in their belief that they held the superior firepower.

But the forest has a way of humbling experts. The rain had been falling for 12 hours straight. The mud was ankled deep. The moisture was inescapable, just as the armorer predicted. The paper shotgun shells in the supply crate were starting to swell. They were soft and mushy to the touch. A regular soldier would have panicked.

A regular soldier would have thrown the weapon down and begged for a rifle. Vance wasn’t a regular soldier. He sat in his foxhole at night, huddled under a poncho with a small candle, burning between his boots. He took the shells out one by one. He dipped the paper holes into the hot wax, sealing them against the moisture.

Then he coated them in a thin layer of axle grease he’d scraped off a Jeep’s wheel hub. He was waterproofing his ammunition by hand, creating a custom load that would cycle through the Winchester’s action as slick as oil on glass. While the others slept or complained about the cold, Vance was preparing.

He checked the action of the Model 97. The mechanism was archaic. It didn’t have a trigger disconnector. That was a safety feature found on modern pump shotguns that forced you to release the trigger and pull it again for the next shot. The Model 97 had no such safety. If you held the trigger down and pumped the slide, the hammer would drop the instant the bolt locked forward.

It was a feature called slam firing. It meant the rate of fire was limited only by how fast you could wreck the slide back and forth. Vance sat in the freezing dawn, his thumb resting on the exposed hammer of the shotgun. The fog was beginning to lift just enough to reveal the jagged line of black earth about 50 yards ahead. the dragon’s teeth.

It was a trench system the Germans had dug to protect the approach to the ridge. Three lines of interconnected ditches reinforced with logs and machine gun nests. The platoon had tried to take it twice in the last 24 hours. Both times the German MG42 machine guns, the Hitler’s buzz saws, had cut them to pieces before they got within grenade range.

The order had come down from HQ at 0530. They were going again. This time there would be no artillery support. The trees were too thick and the friendly lines were too close. It was going to be a frontal assault. Infantry against machine guns. Suicide by any other name. Lieutenant Miller crawled down the line, his face pale and tight. He stopped at Vance’s foxhole.

He didn’t make a joke this time. He just looked at the shotgun, then at Vance and shook his head with a grim resignation. Keep your head down, Vance, Miller whispered. Just try not to get in the way. Vance nodded. He cycled the action of the Winchester. Clack clack. The sound was heavy, mechanical, and reassuring.

He loaded five wax dipped shells into the tube and chambered a sixth. He stuffed a handful of loose shells into his jacket pocket where he could reach them fast. He watched the German line. He saw the subtle movement of a helmet rim above the dirt. He saw the barrel of a machine gun traversing. The expert said he was holding a toy. The expert said he was brought a bird gun to a war.

The experts were about to find out that in the dark, tangled hell of the Huichin forest, a bird gun was exactly what you needed to clear the nest. The whistle didn’t sound like a whistle. In the thick, wet air of the Huichin, it sounded flat and distant, like a child’s toy being stepped on. But the reaction was instant.

30 men surged up from the mud, scrambling over the slick roots and diving forward into the gray mist. For the first 3 seconds, there was silence. Just the sound of boots sucking out of the muck and the heavy breathing of men trying to sprint with 60 pounds of gear. Then the forest exploded. The German MG42 machine gun opened up from the center of the trench line.

The sound of that weapon is something you never forget. An American machine gun goes rattat. It has a rhythm. The German MG42 fired 1,200 rounds a minute. It didn’t have a rhythm. It sounded like canvas tearing. It sounded like a zipper being ripped open by a giant hand. The lead squad disintegrated. The bullets didn’t just hit the men.

They chewed through the trees they were hiding behind. The pinewood shattered into millions of jagged splinters, turning the forest itself into shrapnel. Men dropped, screaming, clutching their legs and stomachs. The rest of the platoon dove for cover, pressing their faces into the freezing mud. Lieutenant Miller was screaming orders, but nobody could hear him over the roar of the machine guns.

He was pinned behind a rotting log. His Thompson submachine gun jammed into the dirt. He tried to rise up to fire, but a burst of German lead sawed through the top of the log, sending a spray of wood chips into his face. He scrambled back, wiping the debris from his eyes, looking around in panic.

The attack was dead on arrival. They were stuck in the kill zone, and the Germans were just getting started. To the right of the lieutenant, a private tried to return fire with his M1 Garand. He popped up, leveled the rifle, and pulled the trigger. Click. The action didn’t cycle. The freezing rain had turned the oil in the receiver into a gummy paste, and the mud from the initial dive had clogged the operating rod.

The private frantically racked the bolt, trying to clear the jam, but he was fumbling with numb fingers. A German rifleman in the trench 40 yard away didn’t have that problem. His bolt-action car 98 was simple, sealed, and deadly. He put a single round through the private’s helmet before the American could even get a shot off.

The superior American firepower was failing. The high-tech semi-automatic rifles were choking on the filth of the forest. The experts who designed these weapons in clean laboratories hadn’t planned for the Huichin mud. Harlon Vance didn’t pop up. He didn’t try to aim down sights. He watched the scene with the detached focus of a man waiting for a flock of ducks to turn into the wind.

He saw the pattern. The German machine gun was sweeping left to right, locking down the center. But on the far left flank, there was a gap. A section of the trench line obscured by a dense thicket of holly bushes. The Germans were ignoring it because the brush was too thick to shoot through.

They assumed no American would be stupid enough to try and push through a wall of thorns. Vance looked at the lieutenant who was busy shouting into a radio that wasn’t working. He looked at the pin squad. Then he looked at his shotgun. Vance didn’t ask for permission. He rolled onto his stomach and began to crawl.

He didn’t crawl like a soldier on his elbows and knees. He crawled like a reptile, flat against the earth, using his toes and fingertips to pull himself through the slush. He moved toward the holly bushes on the left. The thorns tore at his uniform and scratched his face, but he didn’t stop. He dragged the Winchester Model 97 through the mud, the wax dipped shells in the magazine tube protected from the grime.

He reached the edge of the German trench line unseen. He was 10 ft away from the first position. He could smell the enemy, the acrid scent of cheap tobacco and unwashed wool. He rose to a crouch. Below him, in a dugout reinforced with logs, two German soldiers were reloading their rifles.

They were focused on the slaughter happening in the center of the field. They were laughing. One of them said something in German and pointed at the pinned Americans. Vance stepped onto the lip of the trench. He didn’t yell, “Hands up.” He didn’t hesitate. He racked the slide. Clack clack. The sound was so distinct, so heavy and mechanical that both Germans froze.

It was the sound of a coffin lid slamming shut. They looked up. They saw a dirty, exhausted man from Kentucky holding a weapon their grandfathers had learned to fear in 1918. Vance pulled the trigger. The first blast hit the German on the left. At 10 ft, a load of doubleot buckshot doesn’t spread much. It hits like a sledgehammer.

The German was lifted off his feet and thrown back against the log wall of the dugout. The second German scrambled for his rifle, his hands slipping on the bolt. Vance didn’t just pull the trigger again. He slammed his hand backward, working the pump action with a violence that threatened to tear the gun apart.

The wax goated shell ejected perfectly, spinning through the air, and the fresh round slammed home. Vance held the trigger down as he shoved the pump forward. Boom! The second German crumpled. The recoil of the Model 97 was brutal. It had a steel butt plate that dug into your shoulder like a dull knife. Vance didn’t feel it.

He jumped down into the trench, his boots landing on the wooden duckboards. The trench was narrow, barely wide enough for two men to pass. It smelled of wet earth and cordite. To his right, the trench zigzagged toward the main machine gun nest. To his left, it led to a bunker complex. Vance turned right. He was inside the dragon’s teeth now.

He was the fox in the hen house. A German officer came around the corner. An MP40 submachine gun slung across his chest. He was sprinting, reacting to the noise. He ran straight into Vance. The distance was less than 5 ft. The German tried to raise his weapon, but the barrel caught on the trench wall.

Vance didn’t even shoulder the shotgun. He fired from the hip. This was point shooting. This was shooting a rabbit bursting from a bush. The blast caught the officer in the chest. The force of it knocked him backwards so hard he somersaulted over his own boots. Vance pumped the slide. Clack clack. Smoke poured out of the ejection port, thick and gray.

Up on the surface, the firing had changed. The German machine gun stopped its rhythmic tearing. The gunners were confused. They heard explosions inside their own lines. Lieutenant Miller, still pinned behind his log, lifted his head. He saw the muzzle flashes erupting from the German trench.

He saw a helmet go flying into the air. He didn’t see a Thompson. He didn’t see a garand. He heard the deep, throaty roar of a 12- gauge shotgun. Boom! Clack! Clack! Boom! It was a slow, deliberate cadence. It sounded like a pile driver working. “He’s in!” someone shouted. The crazy bastard is in the trench. Vance was moving fast.

He knew that if he stopped, he died. The Model 97 held five rounds in the tube and one in the chamber. He had fired three. He had three left. He reached the corner of the trench that led to the machine gun nest. He could hear the crew shouting, trying to turn the heavy MG-42 around to face the rear. They were panicking. They were used to fighting enemies in front of them, not behind them.

Vance took a breath. He reached into his pocket and pulled out two of his wax dipped shells. With a fluid motion he had practiced a thousand times in the cornfields of Kentucky, he shoved them into the bottom of the receiver, topping off the magazine without opening the action. He swung around the corner.

The machine gun crew was there. Three men, one on the gun, one feeding the belt, one spotting. The gunner was wrestling with the tripod trying to spin the heavy weapon. The loader saw Vance first. He pulled a Luger pistol from his belt. Vance fired. The loader dropped. Vance kept the trigger depressed and slammed the pump back and forth. Boom.

The gunner took the second round. The spotter tried to dive for a grenade. Boom. Vance caught him in midair. The silence that followed was deafening. The MG42 was quiet, the immediate threat to the platoon was gone. Vance stood there, his chest heaving, the barrel of the Winchester smoking hot in the freezing rain. The smell of burnt gunpowder and melted wax hung heavy in the narrow ditch.

He had cleared the first line. He had done what the artillery and the tactics and the expert weapons couldn’t do. He had punched a hole in the German defenses with a tube of birdshot, but the silence didn’t last. From further down the trench line, a whistle blew. Not a weak American whistle, but the sharp trilling sound of a German command.

Vance heard the heavy thud of boots on wood. A lot of boots, reinforcements. The Germans realized the breach. They weren’t retreating. They were swarming. A squad of stormtroopers, heavily armed and wearing armor vests, was rushing down the communication trench toward his position. Vance looked back at the lip of the trench where his platoon was supposed to be.

They were still crossing the field. They were at least 20 seconds away. Vance was alone. He had three rounds left in the gun. He could hear the Germans screaming as they charged, their voices echoing off the mud walls. He checked his pocket. He had 12 shells left. 12 shells against the entire German counterattack. He racked the slide, chambering a fresh round.

He didn’t climb out. He didn’t retreat. He turned toward the sound of the approaching boots and waited. The mockery was over. Now it was just survival. The trench was shaped like a jagged scar in the earth. A series of sharp 90deree turns designed to stop exactly what Harlon Vance was about to do.

If a shell landed in one section, the blast would be contained by the earthn walls. But those walls also meant you couldn’t see what was coming around the corner until it was close enough to smell. Vance pressed his back against the wet logs of the revetment. He could hear the German stormtroopers sprinting down the duckboards.

Their gear was rattling, cantens against belt buckles, bayonets against rifles. They were shouting to each other, a chaotic mix of orders and confusion. They knew the machine gun was down, but they didn’t know why. They expected a squad of Americans. They weren’t expecting a single man with a pumpaction anacronism.

Vance shifted his grip on the Winchester. His hands were slick with rain and sweat, but the checkering on the walnut pump handle dug into his skin, giving him a purchase that felt like a handshake from an old friend. He didn’t look at the corner. He looked at the mud wall opposite the corner. He was watching for the shadow.

A split second later, a dark shape flickered against the dirt. Vance stepped out. The lead German was huge. A corporal with a thick wool coat and a stick grenade in his hand. He was 5 yards away. He never got the chance to throw it. Vance held the trigger down and slammed the slide back. The hammer dropped. Boom.

The buckshot hit the German’s chest like a bag of wet cement dropped from a second story window. The impact didn’t just kill him. It stopped his forward momentum instantly, dropping him in a heap that blocked the narrow path. The soldier behind him tried to fire over his comrade’s falling body. Vance racked the slide.

The empty waxcoated shell flew out, spinning in the air. The fresh shell slammed home. Boom. The second shot tore through the wooden support beam next to the German’s head, sending a shower of splinters into his eyes. He screamed and flinched. Vance pumped again. Boom. The third shot silenced him. This was the slamfire capability in its terrifying glory.

There was no pause, no disconnect, no thinking. It was a rhythm of pure destruction. Rack bang, rack bang. It turned the shotgun into a manual machine gun that didn’t jam, didn’t overheat, and didn’t care about the mud. But the rhythm had a limit. Vance counted the shots in his head. Four, five, six. The slide locked back. The gun was empty.

The brereech lay open, smoking, revealing the empty red follower of the magazine tube. Vance ducked back behind the corner just as a burst of submachine gun fire chewed up the mud where his head had been a second earlier. The Germans were suppressing the corner. They knew he was dry.

They could hear the difference between a pause and a reload. They were coming. Vance didn’t panic. He didn’t fumble. He reached into his wet jacket pocket and grabbed two shells. He didn’t try to stuff them into the magazine tube at the bottom. That took too long. He dropped one shell directly into the open ejection port on the side of the gun and slammed the slide forward.

It’s called a combat load. It took him less than a second. As the bolt closed, a German soldier dove around the corner, bayon it fixed, screaming. He landed on his knees, ready to thrust upward into Vance’s gut. Vance didn’t even shoulder the weapon. He fired from the hip, the muzzle inches from the Germans helmet. The blast was so close it set the soldier’s tunic on fire.

The German collapsed backward. Vance immediately flipped the shotgun over, stuffing three more shells into the tube while keeping his eyes on the bend. His fingers moved with the muscle memory of a man who had reloaded on the ski range thousands of times where a slow reload meant a lost trophy. Here it meant a lost life.

He didn’t wait for them to regroup. The experts would have told him to hold the position and wait for backup. The experts would have said he was overextended. Vance knew that in a trench fight, momentum was the only armor you had. If you stopped, they would grenade you. If you moved, they had to react to you.

He racked a fresh round and charged. He sprinted down the communication trench, screaming. It wasn’t a brave scream. It was a primal noise, a way to force the adrenaline into his veins and terrify the men waiting for him. He rounded the next bend and found a dugout entrance. Three Germans were huddled inside, trying to set up a mortar to fire on the American wave. They looked up, eyes wide.

Vance didn’t slow down. Boom. He took the mortar man. Clack clack. Boom. He took the loader. The third German raised his hands, dropping his rifle. Vance didn’t shoot. He rushed past him, smashing the steel butt plate of the shotgun into the man’s jaw, knocking him cold. You couldn’t leave enemies behind you, but you couldn’t waste shells on men who weren’t shooting.

Vance was now 30 yards deep into the enemy line. He had cleared two sectors single-handedly. His shoulder felt like it had been hit with a baseball bat. His ears were ringing so loudly he couldn’t hear the rain, but he could feel the vibration of the ground. The rest of the platoon was finally hitting the first trench line.

He heard the distinct ping of M1 Garin clips ejecting and the chatter of Thompson submachine guns. The cavalry had arrived. Lieutenant Miller dropped into the trench first, his boots skidding on the slick wood. He almost tripped over the body of the German officer Vance had killed minutes earlier.

Miller looked wildeyed, his helmet crooked, his Thompson searching for a target. He saw the carnage. He saw the machine gun crew dead at their post. He saw the bodies piled in the narrow walkway. And then he saw Vance. The corporal was standing at the junction of the second trench line, reloading again.

He looked like a statue made of mud and violence. His uniform was torn, his face was black with soot, and he was calmly pushing wax dipped red shells into the belly of the Winchester. Miller opened his mouth to shout an order, to ask a question, to say something, but the words died in his throat. Suddenly, a hidden door in the trench wall, a spider hole covered by burlap, burst open behind the lieutenant. A German soldier emerged.

A Luger pistol raised, aiming directly at the back of Miller’s head. The lieutenant didn’t see him. The soldier’s finger tightened on the trigger. Vance didn’t yell, “Look out!” He didn’t have time. He swung the long barrel of the shotgun over the lieutenant’s shoulder. The muzzle blast was so close it singed the hair on Miller’s neck. Boom.

The German soldier was thrown back into his hole as if he’d been yanked by a cable. The sound in the confined space was deafening. Miller spun around, falling against the trench wall, staring at the dead man who had been a millisecond away from killing him. He looked back at Vance. Vance just racked the slide. Clack clack.

A fresh shell popped into the chamber. Clear, Vance said. His voice was raspy, dry, and surprisingly quiet. The rest of the squad poured into the trench behind them. They were panting, terrified, running on pure adrenaline. They saw the bodies. They saw the smoking shotgun. They saw their birdie standing over the ruins of a German counterattack.

The mockery died right there in the mud. Nobody laughed. Nobody cracked a joke about duck hunting. They looked at the model 1897 with a new kind of understanding. It wasn’t a toy. It wasn’t a relic in the hands of a man who knew how to work it. It was the most efficient killing tool in the forest. The firing line began to stabilize.

The Americans spread out, securing the dugouts, turning the German machine guns around to face the ridge. The hill was theirs. The impenetrable dragon’s teeth had been cracked open by a farm boy who refused to listen to the people who knew better. Vance sat down on an ammo crate. His hands were shaking now.

The adrenaline dump was hitting him. He set the Winchester down across his knees. The barrel was hot enough to hiss when the raindrops hit it. He reached into his pocket and found it was empty. He had fired 21 rounds in less than 2 minutes. He had cleared three trench sectors, killed or incapacitated a dozen enemy soldiers, and broken the back of the German defense.

He took a deep breath of the cold metallic air. He wasn’t thinking about the metals they would try to pin on him. He was thinking about how long it would take to clean the melted wax out of the receiver. The rain didn’t stop. It never stopped in the Huichin forest, but the noise had changed. For 40 minutes, the air had been filled with the tearing sound of machine guns and the wet thud of mortars.

Now there was only the sound of heavy breathing and the dripping of water off helmet brim. The trench line, Hill 203, was secure. The dragon’s teeth, the defensive line that had chewed up two entire battalions, had been cracked open by a single man crawling through the mud. Harlon Vance sat on a wooden ammunition crate, his head hanging low between his knees.

The adrenaline dump was hitting him hard now. His hands, which had been steady enough to reload a shotgun while running into machine gun fire, were now trembling uncontrollably. He tried to light a cigarette, but the match kept snapping in his wet fingers. He didn’t look at the corner. He looked at the mud wall opposite the corner.

He was watching for the shadow. A split second later, a dark shape flickered against the dirt. Vance stepped out. Lieutenant Miller walked over. The officer had lost his helmet somewhere in the scramble. He had a bandage wrapped around his left hand where a splinter from a tree burst had caught him.

He stood over Vance for a long time just looking at the Winchester Model 97 resting across the corporal’s lap. The gun was filthy, the wood was gouged, the finish was gone, and the barrel was caked in carbon, but the action was open. It was ready. Miller didn’t make a speech. He didn’t quote the field manual. He reached into his tunic, pulled out his own silver Zippo lighter, and flicked it open.

He held the flame to the end of Vance’s unlit cigarette. Vance took a drag, the smoke mixing with the cold air, and looked up. The mockery was gone. The arrogance was gone. In the lieutenant’s eyes, there was only a profound, terrified respect. “I’m putting you in for a silver star, Vance,” Miller said quietly.

Vance shook his head, exhaling a plume of smoke. “Don’t bother, sir. Just tell the armor to get me more doubleot buckshot and tell him to bring me some more candles. I’m running low on wax. The story of birdie Vance and the hill 203 trench raid didn’t stay in the forest. It traveled back to the rear echelon passed from foxhole to foxhole like a sacred legend.

The men who had laughed at the hillbilly weapon stopped laughing. Suddenly, every platoon leader in the fourth infantry division wanted a trench sweeper. They raided the supply depots, looking for dusty crates of Model 97s that had been left over from the First World War. The armorers, the experts who had sneered at the paper shells, were forced to adopt Vance’s method.

They started setting up makeshift workshops in abandoned barns, melting down church candles, and dipping shotgun shells by the thousands. They called them Vance specials, but the war didn’t end that day. Vance survived the Huichin forest, but the forest took a piece of him that he never got back. He fought through the battle of the bulge, carrying that same battered Winchester through the snow of the Ardens.

He cleared farmhouses in Germany, street corners in Cologne, and basement in the Roar Pocket. He became a specialist in the kind of violence that most men couldn’t stomach. The shotgun wasn’t a precision instrument. It was a grim reaper scythe. It was messy. It was personal. And Vance was the best there was at using it.

By May 1945, when the Germans finally surrendered, Vance was a staff sergeant. The Winchester Model 97 had fired hundreds of rounds. The pump handle was worn smooth by the friction of his hand. The internal parts were held together by luck and axle grease. When the order came to stand down, Vance didn’t cheer. He didn’t celebrate.

He sat on the running board of a halftrack, unloaded the weapon for the last time, and carefully wiped it down with an oily rag. He treated it with the respect you give a dangerous animal that has decided not to bite you. Vance returned to Kentucky in the fall of 1945. The train dropped him off at the station in Louisville and he took a bus back to his family’s farm.

He didn’t talk about the war. When his father asked him how it was over there, Vance just said it was cold and walked out to the barn. He unpacked his sea bag. Inside, wrapped in a wool blanket, was the Model 97. He had brought it home, not as a trophy, but because he didn’t trust anyone else to own it. He took the gun to the back of the house, to a storage closet under the stairs that smelled of cedar and mothballs.

He placed the shotgun in the furthest corner behind a stack of old quilts. Then he closed the door. He never opened it again. Haron Vance lived another 50 years. He got married, raised three daughters, and worked as a foreman at a lumber yard. He was a pillar of his community, a deacon in his church, the kind of guy who would stop to help you fix a flat tire in the rain.

And he hunted. Every fall when the leaves turned brown, he would go out into the fields with his friends to hunt quail and feeasant. But he never used a pumpaction shotgun. He bought a sleek overunder doublebarrel sporting gun. He shot clay pigeons on the weekends. He taught his grandsons how to lead a target, how to breathe, how to respect the weapon.

But sometimes when a thunderstorm rolled in over the Kentucky hills and the thunder cracked like an artillery barrage, his family would find him sitting on the back porch staring at the treeine with a thousand-y stare. They didn’t know he was back in the huin. They didn’t know he was smelling the cordite and the wet pine needles.

They didn’t know he was hearing the clack clack of a slide that sounded like a coffin lid closing. Vance died in his sleep on November 18th, 1999, exactly 55 years to the day after he cleared the trenches on Hill 203. When his family cleaned out the house, they found the closet under the stairs.

They found the Winchester. It was rusted shut. The steel had pitted and the wood had cracked. It was a ruin, but taped to the stock was a small yellowed piece of paper. It was a note from Lieutenant Miller written on a scrap of Kration cardboard in 1944. It just said for the bird hunter, you were right. The family donated the rifle to a local VFW hall.

For years, it hung on the wall above the pool table, just another old gun gathering dust and cigarette smoke. People walked past it every Friday night without looking. They saw a piece of junk. They saw a rusty relic that looked like it belonged in a scrap heap. They didn’t see the weapon that had saved 30 men from annihilation.

They didn’t see the tool that had proven the experts wrong. We tell this story because Harland Vance represents something that is disappearing from our world. We live in an age of technology where we trust the algorithm, the data, and the experts to solve our problems. We trust the smart solution, but in the mud and the blood of the real world, the smart solution often fails.

Sometimes you don’t need a microchip. Sometimes you need a candle, a pot of grease, and the courage to ignore the people laughing at you. Vance didn’t fight for glory. He didn’t fight to prove a point. He fought because he looked at the problem, looked at his tool, and realized he was the only one who could fix it.

He was a craftsman of survival. So, if this story of the birdie who became a wolf moved you, do me a favor. Hit that like button. It’s a small thing like dipping a shell in wax, but it makes a difference. It tells the algorithm that these stories matter. It tells the system that we haven’t forgotten the men like Harlon Vance.

And if you have a family member who served who had a MacGyver moment where they had to improvise to survive, drop a comment below. We want to hear it. We want to rescue these stories from the silence before they’re gone forever. Subscribe to the channel, turn on notifications, and join us next time because history isn’t just dates and maps.

It’s the sound of a pumpaction shotgun in the mist. It’s the smell of burnt powder. It’s the people who walked into the fire so we wouldn’t have to. Thanks for watching.