Let me ask you something. What happens when the best soldiers in the world realize they’re not? When Navy Seals, the guys who wrote the book on unconventional warfare, meet allies who make them look amateur. When 80 lb rucks sacks, cutting edge radios, and American firepower get outperformed by four Australians with 40 pound packs, and zero technology.

April 1967, NHAB air base. The day American confidence shattered. The day seals learned that the deadliest weapon in Vietnam wasn’t a gun. It was silence. And the Australians had mastered it for decades. You think you know the Vietnam War? You don’t know this. The helicopter touched down at Nai Air Base and four men stepped onto the tarmac carrying packs that looked almost insultingly small.

No visible radio antennas jutting skyward. No heavy weapons cases. No mountains of ammunition that American doctrine considered absolutely essential for survival in hostile territory. The Navy Seals watching from the operations building exchanged confused glances. Someone in the logistics had clearly made a serious error.

Maybe the Australians real equipment was coming on the next bird. Maybe this was some kind of advanced party traveling deliberately light. It was not a logistics error. It was the beginning of the most humiliating education in American special operations history. Those four small packs weighing roughly 40 pounds each contained everything the Australian Special Air Service Regiment considered necessary for extended jungle operations lasting weeks.

Not the minimum for a short patrol, not a stripped down emergency kit. Everything. The entire philosophy of what a special operator needed to survive, move, engage, and vanish had been compressed into half the weight American SEALs carried a standard loadout. But the real shock was still 72 hours away.

And when it came, it would shatter everything these elite American warriors thought they knew about their profession. Within 3 days, those same seals would be lying motionless in ambush positions deep in the Vietnamese bush, covered in mud, surrounded by insects, stripped of half the gear they had trained with for years, and asking themselves a question that would haunt them for the rest of their careers.

Uh, had they been fighting the wrong war this entire time? What happened at NAB in April of 1967 was never supposed to become public knowledge. The joint training program between Australian SASR and US Navy Seals remains one of the most consequential and deliberately obscured chapters in special operations history.

The Australian War Memorial Archives confirm it existed. Declassified American documents verify that SASR personnel provided instruction at facilities including Inhab and Vong Tao. Official SASR regimenal history acknowledges that Australian instructors were embedded with MACV recondo school. But here is what those official records do not tell you.

The specific lessons taught during those training sessions. The precise techniques transferred from Australian minds to American hands. The documented results when those techniques were applied in actual combat. Large portions of those records have never been fully released. And what has been declassified suggests something that made Pentagon analysts deeply uncomfortable then and continues to complicate official narratives today.

A small allied nation with a fraction of American resources had developed jungle warfare methods that consistently outperformed the most technologically advanced military on Earth. Not by small margins, by factors that defied conventional military logic. Here is the comparison they did not want anyone making.

And here is why it still matters more than 50 years later. American special operations doctrine in 1967 represented the pinnacle of Western military thinking. The Navy Seals watching those Australians arrive were products of the most demanding selection and training process the United States had ever created. They had survived hell week.

5 and a half days of continuous physical torture designed to break anyone who could be broken. They had mastered underwater demolition, close quarters combat, parachute insertion, and a dozen other specialized skills. They carried cutting edge communications equipment that could reach headquarters from anywhere in Southeast Asia. Their rucks sacks weighed approximately 80 pounds.

Packed with every contingency item that decades of institutional experience had deemed essential, the philosophy was straightforward and had been proven in the biggest wars humanity had ever fought. bring overwhelming capability into the field, dominate any engagement through superior firepower, use technology to compensate for any disadvantage in numbers or terrain.

This was the American way of war, and it had crushed Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan within living memory. Australian doctrine said the opposite, and that contradiction was about to explode in the faces of America’s finest warriors. The SASR approach had not been developed in air conditioned classrooms or theoretical war games.

It had been forged through years of brutal counterinsurgency in Malaya starting in 1950, refined through the Borneo confrontation of the early 1960s, paid for in blood by Australian soldiers who had buried friends because of mistakes that seemed trivial until they proved fatal. Heavy packs did not provide security through superior firepower.

They reduced mobility and created noise that betrayed position. Radios did not guarantee safety through access to air support. They created electronic signatures that sophisticated enemies could detect. Excessive ammunition did not ensure survival. It encouraged firefights that should never happen if the patrol was operating correctly.

But here is what made the Australian philosophy truly revolutionary and truly terrifying to American institutional thinking. The goal was not to win engagements and the goal was to ensure that engagements never happened on enemy terms. The objective was not firepower dominance. The objective was information dominance achieved through perfect invisibility.

You cannot lose a fight that never occurs. And you cannot be defeated by an enemy who never knows you exist. This was not a refinement of American doctrine. This was its complete philosophical opposite. The gear inspection that occurred on the second day became legendary among every American who experienced it. The Australian instructors asked the SEALs to empty their rucks sacks completely.

Every single item laid out on the ground for review. 80 pounds of carefully selected equipment spread across the packed earth in neat rows. Radios with spare batteries. Ammunition in quantities that would sustain hours of combat. Medical kits comprehensive enough for field surgery. Rations for extended operations.

water containers, grenades of every variety, signal flares, climbing equipment, spare clothing, emergency supplies. The accumulated technological wisdom of American special operations compressed into one very heavy backpack. The Australian instructors walked along the line of gear with expressions that revealed nothing.

They examined every item, hefted packs, asked questions about purpose and necessity. Then they pointed to roughly half of everything on the ground and delivered three words that would reshape how American operators thought about warfare forever. Leave it behind. The protests erupted immediately and every single objection was entirely reasonable by American training standards.

The radio was missionritical for calling air support when engagements went badly. The ammunition was survival itself and sustained firefights. The medical kit could mean the difference between an operator going home and an operator going home in a bag. Every item had been selected through rigorous institutional processes approved by commanders with combat experience.

Validated through operations around the world. You did not simply abandon gear that doctrine required. That was not how professional militaries operated. The Australian response was not an argument. It was a single question that silenced every protest more effectively than any lecture could have managed. If the enemy knows where you are, what good is the radio that calls in the air strike that arrives after you are already gone? Silence.

Complete silence from the American side. This was not a tactical adjustment to be debated and potentially rejected. This was philosophical demolition of assumptions that Americans had never thought to question. The entire American approach assumed that superior firepower could compensate for compromised position. Get detected, fight your way out, take casualties, call for medevac, mission going sideways, request air support, and overwhelming reinforcement.

The Australian approach assumed something entirely different. Compromised position meant mission failure. Regardless of what firepower you had available, detection was not a problem to be solved through combat. Detection was the end of everything the patrol was supposed to accomplish. But the weight reduction was only the first revelation.

What came next made grown men question whether they had been fighting the wrong war for 6 years. The Australians explained that the Vietkong possessed sensory capabilities that American intelligence had consistently and catastrophically underestimated capabilities that sounded almost supernatural when first described, but were entirely natural and entirely lethal. specifically smell.

The enemy could literally detect American presence through scent signatures that Western soldiers did not even know they were producing, not body odor in the conventional sense. Something far more insidious. deodorant, soap, toothpaste, laundry detergent, shaving cream, aftershave, boot polish, gun oil. Every product that American culture considered essential for basic military professionalism left chemical traces in the human jungle air.

Traces that announced foreign presence as clearly as a signal flare to anyone trained to recognize them. The Vietnamese jungle had specific organic odors that local populations absorbed through lifetime exposure. Fish sauce, rice patties, tropical vegetation in various stages of growth and decay, wood smoke from cooking fires, animal waste, the soil itself.

The Vietkong grew up marinating in these smells. Their noses were calibrated to detect anything that did not belong. An American operator who had showered with standard military soap that morning might as well have been carrying a neon sign announcing his position. The chemical signature was alien to the environment. Detectable from distances that would shock anyone operating on western assumptions about how smell worked.

The Vietkong did not need sophisticated electronic detection equipment to find American patrols. They just needed to sniff the breeze and follow the scent of Colgate toothpaste through the jungle. The smell doctrine that Australians taught was simple in concept and brutal in execution. Stop smelling like Americans. No western hygiene products for a minimum of 3 days before any patrol, no soap, no deodorant, no toothpaste, no shaving cream, nothing that would mark you as foreign to the oldactory landscape of the jungle. Some Australian units went

even further, eating local food when possible, rubbing themselves with jungle vegetation. Some reportedly used fish sauce to mask any residual foreign scent. The goal was not just to eliminate American smell. The goal was to smell like you belonged in the environment you were operating in. The seals who heard this instruction reportedly looked physically ill.

And their reaction was entirely understandable. The idea violated everything American military training taught about professionalism and bearing. Clean soldiers were disciplined soldiers. Proper hygiene was fundamental to unit cohesion and individual effectiveness. These were not suggestions in American military culture.

These were core values that had been drilled in from the first day of basic training. But the instruction also violated something even deeper. Cultural assumptions about cleanliness that went to the core of American identity. These were young men raised in a society that viewed personal hygiene as a marker of civilization itself.

asking them to stop washing, stop using deodorant, stop brushing their teeth with familiar products, was asking them to abandon part of who they were as modern western people. The Australians were not asking for opinions on the matter. They were explaining with brutal clarity why American patrols kept getting detected regardless of how carefully they moved or how well they camouflaged their visual signatures.

You could paint your face in the most elaborate camouflage pattern ever devised. You could cover yourself head to toe in local vegetation. You could move with perfect silence through the densest undergrowth. None of it mattered if you smelled like a Proctor and Gamble factory. But the smell doctrine was only the beginning of the transformation.

What came next challenged American assumptions about movement itself. The training that followed introduced techniques that had never appeared in any American military manual. The SASR shuffle was a method of movement so slow, so deliberate, so utterly contrary to American tactical instincts that it seemed almost absurd when first demonstrated.

American training emphasized speed. Move quickly through danger zones. Minimize exposure time. The faster you cross dangerous ground, the less time the enemy has to detect and engage you. This made intuitive sense. This was how Americans approached almost every tactical problem. The Australian technique required something entirely different.

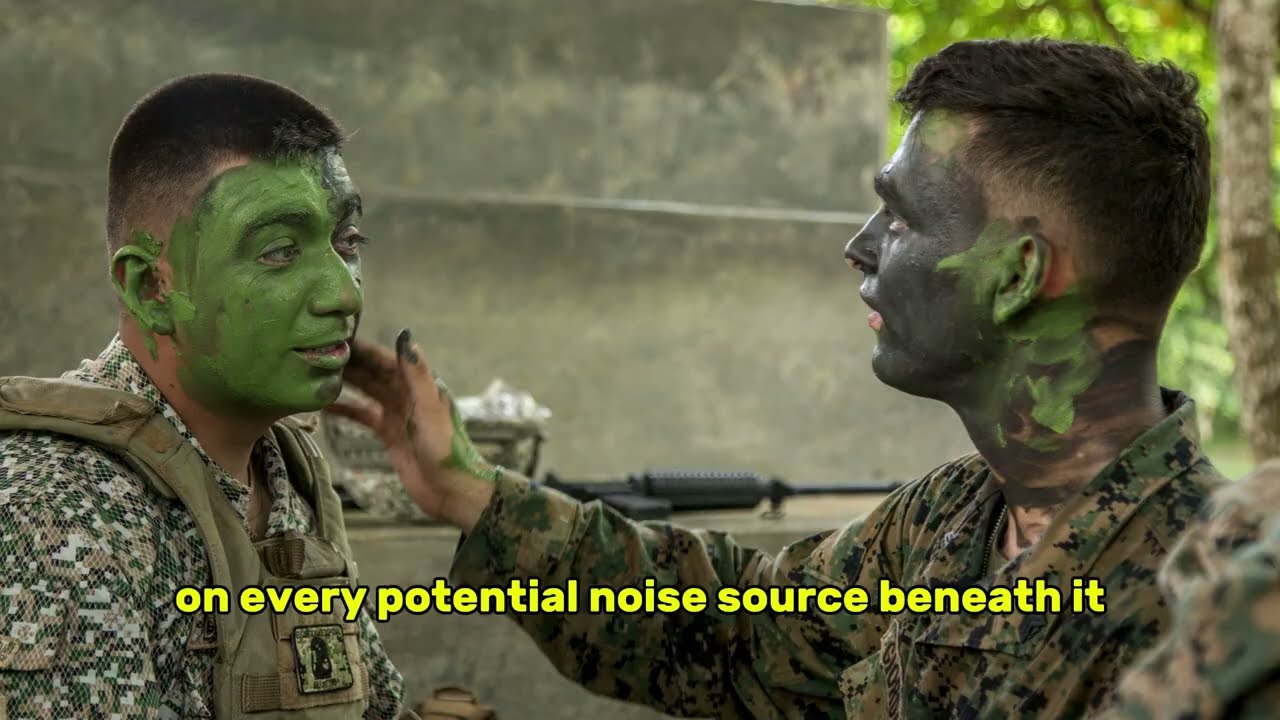

One foot lifting with excruciating care, hovering in the air while the operator assessed the terrain ahead with complete attention, moving forward mere inches at a time, then descending with obsessive focus on every potential noise source beneath it. Twigs that might snap underweight, leaves that might rustle with disturbance, loose soil that might shift and crunch, standing water that might splash.

Every footfall became a discrete operation requiring complete concentration and perfect muscular control. A distance that American doctrine said should take 10 minutes could take Australian patrols 2 hours or 4 hours or longer if the situation demanded it. The speed was so slow that it barely qualified as movement by conventional military standards.

It looked like freeze frame footage of soldiers inching through vegetation punctuated by long pauses where nothing visible happened at all. Every American instinct screamed that this was wrong. Slower meant more vulnerable. Slower meant more time in the danger zone. Slower meant giving the enemy more opportunities to detect and engage.

But the mathematics told a completely different story. The enemy cannot engage what the enemy cannot locate. Australian patrols had demonstrated the ability to remain undetected in hostile territory for periods that American doctrine considered flatly impossible. Not through superior technology, not through exotic equipment, through superior discipline, through willingness to move slowly enough that no sound betrayed presence, through patience to wait rather than advance when the situation demanded waiting. The jungle punished

impatience with detection, and detection in the jungle meant casualties that no amount of firepower could prevent. But here is where the training took a turn that American operators found genuinely disturbing. The Australians explained what they actually did with the undetected time their methods provided. They did not simply move and observe.

They waited. They established positions and remained in them for periods that seemed medically inadvisable. Here is what American training manuals specified for ambush positions. 50 m minimum distance from the expected enemy route. This provided safety margins that allowed reaction time if something went wrong.

It permitted fire superiority through concentrated firepower at range. It gave options for withdrawal if the engagement deteriorated. Sound doctrine proven effective taught in every special operations school. Here is what the Australians actually practiced. 15 m 15 m less than 50 ft. That is close enough to observe facial expressions on targets.

Close enough to hear individual breathing. Close enough to smell sweat and food and equipment. Close enough that any mistake, a cough, a sneeze, a muscle twitch, and involuntary movement of any kind meant instant discovery in combat at ranges where superior firepower meant absolutely nothing. The reasoning was characteristic of Australian tactical thinking.

At 15 meters, there was no such thing as a missed shot for anyone with basic marksmanship training. At 15 meters, engagements ended before targets could process what was happening, much less react tactically. And at 15 meters, a four-man patrol could neutralize a column of 20 enemy soldiers before any of them managed to unsing weapons and return fire.

But here is the part that never made it into official doctrine. Here is what the training reports did not emphasize. At 15 meters, there were no survivors to report what had happened. The ambush element dissolved back into jungle before anyone who might have escaped could understand what they had witnessed. The only evidence was bodies found later by followon patrols or local civilians.

No information about who had conducted the attack. No intelligence about methods or numbers or direction of withdrawal. Just eliminated personnel and questions that would never be answered. The psychological effect on enemy forces who discovered comrades terminated without any indication of how or by whom exceeded anything conventional tactics could produce.

You could defend against helicopters with anti-aircraft preparation. You could dig tunnels to survive bombing. You could establish warning networks to track American movements. But how do you defend against enemies who appear from nowhere, execute with perfect lethality, and vanish without trace? The answer is you do not.

You simply operate in constant fear and that fear degrades everything you try to accomplish. The mental discipline required for 15 meter ambush doctrine exceeded any training that American selection courses provided at the time. Operators had to lie completely motionless in ambush positions for days, not hours, days. They had to control biological functions for periods that seemed impossible.

They had to allow venomous snakes and biting insects to crawl across their bodies rather than risk the movement required to brush them away. They had to watch enemy soldiers pass within touching distance while suppressing every instinct that millions of years of evolution had programmed into the human nervous system.

The desire to fight, the desire to flee, the desire to simply move after hours of enforced stillness. All of it had to be controlled with iron discipline until the exact moment of execution arrived. Then when that moment came, they had to act with mechanical precision that left no room for hesitation, execute exactly as planned, withdraw exactly as rehearsed, vanish as if the patrol had never existed.

But the training was about to reveal something even more remarkable than ambush technique. The tracking instruction that followed explained why Australian awareness in the jungle seemed almost supernatural to everyone who witnessed it. The techniques SASR operators employed had not originated in military schools or institutional training programs.

They trace lineage to something far older and far more sophisticated. Aboriginal tracking traditions, methods developed over tens of thousands of years, perhaps 40,000 years or more, of continuous human habitation and terrain that demanded perfect environmental awareness for survival. Australian special operations had recognized early in their institutional history that Aboriginal Australians possessed knowledge about tracking and bush survival that no western military training could replicate.

Knowledge accumulated over more generations than recorded history could count. They had actively recruited Aboriginal soldiers and incorporated their expertise into official doctrine. The result was a synthesis of modern military tactics and ancient tracking wisdom that gave Australian patrols capabilities their enemies simply could not comprehend, much less counter.

Where American soldiers had learned to follow obvious signs, footprints and mud, broken vegetation, disturbed ground cover, Australians had learned to read landscapes in ways that seemed like sorcery to the uninitiated. A bent blade of grass communicated how many hours had passed since someone walked through that location.

The specific angle of the bend, the degree of recovery, the color change in stressed vegetation, all of it told a story to anyone who knew the language. The pattern of disturbed insects indicated direction of travel. Certain insects avoided areas of recent human disturbance in predictable ways. Certain others were attracted to the chemical traces humans left behind.

Reading these patterns correctly could tell you not just that someone had passed, but where they had come from and where they were going. Compression in leaf litter revealed information about weight and number of people who had stepped there, how deep the impression, how wide the displacement, whether the walker was moving fast or slow, carrying heavy equipment or traveling light.

Even animal behavior provided actionable intelligence. Wildlife disturbed by human presence exhibited patterns different from wildlife pursuing normal routines. A flock of birds taking flight in one specific way told experienced trackers something completely different than the same birds moving naturally. Monkeys that went silent in one part of the jungle while continuing normal activity elsewhere marked human presence as clearly as a signal fire.

The jungle was not merely terrain to be crossed as quickly and quietly as possible. It was a vast library of information that spoke constantly to anyone who had learned its language. The Australians had spent decades developing fluency. The Americans were only beginning to understand that such a language even existed.

The practical exercises demonstrated the gap between American and Australian capabilities in ways that words could not convey. [snorts] Mixed patrols of Australians and Americans entered the bush surrounding training facilities for tracking exercises. The objective was straightforward. Locate instructor positions using the skills being taught.

Standard training evolution. the kind of exercise American special operations ran constantly. The Americans approached with characteristic energy and confidence. These were SEALs, elite of the elite, veterans of the most demanding selection in the American military. They had trained for years. They knew jungle operations.

They moved along obvious signs, footprints, broken vegetation, disturbed ground, and tried to close distance quickly and efficiently. The Australian instructors detected and theoretically eliminated the American patrol multiple times before any contact was made. Multiple times the same patrol caught completely unaware by small groups of quiet men who seemed to materialize from the vegetation itself with zero warning.

The SEALs were not incompetent. They were among the best soldiers America had ever produced. They had passed tests that washed out 90% of candidates. They represented the absolute pinnacle of American special operations capability, and they had been ambushed repeatedly by four Australians who moved through the same jungle as if they were part of it.

The exercise was designed to shatter assumptions that Americans did not even know they held. It succeeded beyond anyone’s expectations, and the implications extended far beyond the immediate training context. Something profound shifted in the American operators who completed the full Australian program.

The change was difficult to articulate in official reports, but obvious to everyone who knew them before and after. Postwar memoirs from SEALs who went through the instruction described what one veteran called a complete tactical reversal in understanding. Methods that had seemed absolutely essential were revealed as potentially counterproductive in the specific environment of Vietnamese jungle warfare.

Approaches that had seemed impossible were demonstrated as entirely achievable with proper discipline. The entire framework for understanding how special operations should be conducted in this theater had to be rebuilt from first principles. But the training program was only the beginning. The real test would come when American operators took these methods into actual combat.

The ripple effects spread rapidly through American special operations in Vietnam. SASR personnel provided instruction at MACV Recondo School, the premier longrange reconnaissance patrol training facility in country. The lessons reached units across the entire theater. Units that had struggled with consistent enemy detection despite careful tradecraft began reporting dramatically different outcomes after implementing Australian derived techniques.

The changes appeared in afteraction reports, though documentation was often vague about exactly what had changed. Commanders noted improved results without always specifying precise modifications to doctrine. The institutional army was absorbing lessons but not always acknowledging where those lessons originated.

Here is what made those reports significant even in incomplete form. The units applying Australian methods were not receiving new equipment. They were not getting additional personnel. They were not benefiting from changes in enemy capability or terrain or weather or any external variable that might explain improved performance.

The only factor that had changed was technique. The philosophy of how to move, how to wait, how to engage, how to disappear, same soldiers, same weapons, same territory, same enemy, radically different results. The implications troubled institutional army thinking because they suggested something deeply uncomfortable.

Years of doctrine development had been optimized for the wrong variables. American military culture valued technology because technology had won the big wars. Valued firepower because firepower had crushed enemies. Valued aggressive tempo because aggression had seized initiative and dictated terms. Australian experience demonstrated that none of these values applied in the same way to counterinsurgency in dense jungle.

In this specific environment, uh, patience trumped aggression, stealth trumped firepower, environmental adaptation trumped technological superiority, the doctrine that had defeated Nazi Germany was failing against rice farmers in black pajamas, and four Australians with small packs had just shown why. The Vietkong had their own assessment of what was happening in areas where Australians operated, and that assessment revealed more than any American report ever could.

Intelligence captured during and after the war showed that enemy forces had given the Australians a specific designation, a name they did not apply to any other Allied unit in the entire conflict. Ma rung, the forest ghosts, the jungle phantoms. This was extraordinarily significant. The Vietkong did not typically name or differentiate between Allied units.

American forces were fought as institutional enemies. The Marines were different from the Army, primarily in deployment location, not in how they needed to be countered. Various American divisions were essentially interchangeable threats, requiring standardized responses. The Australians were so different that they required separate classification.

Vietkong command structure found it necessary to specifically warn units operating in Australian areas that they face something qualitatively unlike normal Allied forces. The forest ghosts required different precautions because standard anti-American tactics simply did not work against them. The name captured something real about the psychological effect of Australian operations.

And that psychological effect was itself a weapon more powerful than any rifle or artillery piece. You could prepare for American tactics because American tactics announced themselves through unmistakable signatures. Helicopters beating the air before troop deployment. Artillery preparation softening targets. Air support stacking overhead.

Armored vehicles on roads. Radio traffic across the electromagnetic spectrum. The signatures were impossible to miss. You could dig tunnels to survive bombing, establish warning networks to track movements, position forces to counter predictable approaches, prepare ambushes along obvious lines of advance. American tactics were devastating in application but predictable in pattern.

Australian operations offered no such preparation opportunity. Their patrols moved through contested areas without leaving evidence that anyone had passed. No tracks, no broken vegetation, no disturbed wildlife, nothing. It was as if ghosts had drifted through the jungle without touching anything.

Ambushes materialized from positions that had seemed completely empty seconds before firing started. There was no warning, no chance to react, just sudden violence from a direction that reconnaissance had cleared a safe. Key personnel in Vietkong units simply disappeared from their camps without any indication of how enemy forces had penetrated security measures.

That had successfully stopped every American attempt. One day a commander or political officer was there, the next day they were gone. No explanation, no evidence, just absence. The uncertainty was itself a weapon more corrosive than direct combat. Every shadow in the jungle became potential threat when forest ghosts were known to be operating in your area.

Every moment of silence became potential prelude to violence that would arrive without warning. Every patrol became an exercise in terror management. The psychological toll on Vietkong units operating near Australian positions degraded their effectiveness in ways that no body count could measure.

You cannot fight at full capability when you are constantly afraid. You cannot plan effectively when you have no information about enemy movements. You cannot maintain morale when comrades simply vanish without explanation. What the Americans were learning through the training program was not merely a collection of techniques to be added to existing doctrine.

They were learning something far more fundamental. The most effective unconventional warfare was warfare the enemy could not adapt to because the enemy could not understand how it was being conducted. You could develop countermeasures against tactics you understood. Train forces to respond to threats you could anticipate. Evolve doctrine to address capabilities you could observe and analyze but you could not counter an enemy who operated by methods you could not detect using principles you could not comprehend.

The forest ghosts had achieved what all special operations forces aspired to but few ever managed. They had become genuinely unknowable to their enemy and they were teaching Americans how to become unknowable as well. But this transformation came with costs that the official histories rarely acknowledge. And those costs explain why so much about these programs remained classified for so long.

Australian methods demanded psychological changes that left permanent marks on the operators who mastered them. Lying completely motionless for extended periods while every nerve screamed for movement and relief, controlling bladder and bowel functions for hours that stretched into days when tactical necessity required it.

Allowing dangerous wildlife to crawl across exposed skin rather than risk the tiny noise of brushing it away. Watching enemy soldiers pass close enough to touch while suppressing every instinct to fight or flee. Feeling their body heat, smelling their sweat, hearing their conversation, and remaining perfectly still through all of it, then executing at ranges so close that the experience was intimate rather than distant.

Seeing recognition dawn in someone’s eyes in the fraction of a second before that person ceased to exist. Learning to feel nothing in that moment because feeling anything would slow response time and potentially cost your own life. These experience changed men in ways that no debriefing could address and no metal could compensate. Veterans who discussed the training decades later described effects that never fully faded.

Hypers sensitivity to sound that made ordinary civilian environments uncomfortable or unbearable. the inability to fully disengage threat awareness that had become survival instinct. Nightmares that continued for years or decades after the last operation concluded. A fundamental alteration in how they perceived the world and their place in it that could not be reversed once the war ended and normal life supposedly resumed.

The techniques worked brilliantly against the enemy they were designed to defeat. But they required becoming something that was difficult to become and perhaps more difficult to stop being. The forest ghosts earned their name, but many of them would have traded that fearsome reputation for a single peaceful night of sleep. The institutional relationship that began with the 1967 training program did not end when Vietnam concluded.

It evolved into something permanent that persists to the present day. Australian and American special operations forces established ongoing exchange programs that continued through the Cold War and into current conflicts. Techniques refined and jungle warfare were not forgotten. They were preserved, analyzed, adapted for completely different environments.

Desert operations in the Middle East, mountain warfare in Afghanistan, urban combat in environments that looked nothing like Vietnamese bush, but still rewarded the same fundamental principles. of patience, stealth, environmental awareness, the understanding that detection was often more dangerous than engagement.

Modern American special operations carry lineage that traces directly to what was taught at NBE and Vongtao more than 50 years ago. Lineage that is rarely acknowledged in official histories, but obvious to anyone who understands where the methods came from. The emphasis on small unit autonomy that characterizes contemporary special operations.

It developed from Australian demonstrations that small teams operating independently could achieve results that large units with extensive support could not match. The integration of environmental awareness and tracking skills into selection and training. It came from Australian instruction that revealed how blind American patrols had been to information the jungle provided constantly to anyone who knew how to read it.

The understanding that sometimes the best way to complete a mission is to ensure the enemy never knows you were there. That was the core of Australian doctrine transmitted to American students who carried it forward into every conflict that followed. The specific statistics from the training program remain subjects of ongoing debate.

Different sources site different figures for casualty reductions and improved operational outcomes. Some numbers that circulated through the veteran community may have grown through decades of retelling. But what is not debatable is the qualitative transformation that occurred. American operators who trained with Australians came back fundamentally changed and the changes produced measurable improvements and outcomes that even skeptical institutional observers could not dismiss.

The question the comparison raises remains uncomfortable because it challenges assumptions about what determines military effectiveness. The United States possessed overwhelming technological and resource advantages in Vietnam. Advantages that should have translated into dominance by every conventional measure. Australian forces represented a tiny fraction of Allied commitment.

A small contingent from a nation with limited defense budget and modest military tradition by superpower standards. Their special operations community numbered in the hundreds while American special operations numbered in the thousands. Yet, Australian methods achieved results in jungle operations that American methods consistently struggled to match.

Results significant enough that the enemy gave them a special name. Results significant enough that American operators sought Australian instruction. Results significant enough that the lessons learned reshaped how the United States approaches unconventional warfare. To this day, the answer lies in optimization for different variables.

American doctrine had been optimized for conventional warfare against peer adversaries for campaigns where firepower, logistics, and industrial capacity determined outcomes. This optimization had proven spectacularly successful in World War II and Korea. Australian doctrine had been optimized for the specific environment of counterinsurgency in dense jungle for campaigns where information, patience, and environmental adaptation determined outcomes.

This optimization had been developed through painful experience in Malaya and Borneo before being applied in Vietnam. Neither approach was wrong in absolute terms. Both were products of specific historical experience applied to specific strategic challenges. But one approach was wrong for Vietnam and it was not the Australian approach.

The tragedy is that the lessons were available long before America paid the full price for ignoring them. Australian experience from Malaya had demonstrated effective jungle counterinsurgency methodology years before American combat commitment in Vietnam reached significant scale. The techniques that SASR taught to SEALs in 1967 could have been adopted in 1962 or 1963 if institutional willingness had existed.

The cost of that delay is impossible to calculate with precision. How many American casualties might have been prevented by earlier adoption of methods that proved their value? How many operations might have succeeded that instead failed? How many years might have been shaved from a conflict that consumed a generation? The numbers will never be known, but they were clearly substantial.

And that knowledge haunts everyone who understands what was available and what was ignored. The legacy continues in ways that most observers never recognize. When American special operators deploy today with minimal electronic signature, they are using methods demonstrated to skeptical SEALs at NHAB. When they move slowly through hostile terrain rather than rushing through danger zones, they are applying principles that Australian instructors taught more than half a century ago.

When they establish ambush positions at ranges, their training manuals would have once prohibited. When they wait with discipline that seems almost inhuman, when they engage and vanish without trace, they are employing doctrine that traces directly to four quiet men who stepped off a helicopter carrying small packs and no radios.

The student became the teacher. The teacher became the institution. The institution became how America fights. But the original insight remains Australian. The most dangerous weapon in unconventional warfare is not the one that strikes hardest. It is the one that strikes last from a position the enemy never knew existed at a moment the enemy never anticipated, leaving no evidence of how the strike was accomplished.

The methods that the Vietkong feared most were not the methods that arrived with impressive technology. They were the methods that arrived with no warning at all. Four men stepped off a helicopter at Na’vi air base in April of 1967 carrying packs that seemed too small and equipment that seemed too primitive.

The SEALs who watched them arrive made assumptions based on everything their training had taught them. More gear meant more capability. More technology meant more effectiveness. More firepower meant more survivability. Those assumptions were about to be demolished. Those seals were about to discover that the error had been their own.

Years of training optimized for the wrong war. Doctrine developed for the wrong environment. philosophy built on assumptions that the jungle would systematically and mercilessly punish. What the Australians taught over the following weeks was not merely tactics. It was truth. Uncomfortable truth. Humiliating truth. Truth that challenged everything American military culture held dear. Silence defeated firepower.

Patience defeated technology. Discipline defeated doctrine. The forest ghosts had mastered these truths through years of experience that no American shortcut could replicate. Experience paid for in blood and loss and the kind of hard lessons that only failure can teach. They had learned what worked by discovering what did not work.

They had developed methods by burying friends who proved that different methods did not survive, but they were willing to share despite the institutional pride they might have protected despite the competitive instincts that could have led them to hoard their advantages. Although they looked at American allies struggling with the same enemy and decided to help.

The Americans who learned from them became something that even the Vietkong had not anticipated. Warriors who could disappear. Operators who could wait. Hunters who could read the jungle as fluently as their Australian teachers. The forest ghosts had taught the Americans to become ghosts themselves. And in the jungle that was Vietnam, becoming a ghost was the deadliest transformation of all.

The helicopter that brought those four Australian instructors to Nhabi carried more than men and equipment. It carried a philosophy that would reshape American special operations for generations. A philosophy born in the jungles of Malaya, refined in the forests of Borneo, proven in the contested terrain of Fuaktui province.

The philosophy was simple. The execution was anything but. Disappear, wait, execute, vanish. four words that described a complete revolution in how America’s elite warriors understood their profession. The SEALs who completed that training never forgot what they learned. They carried those lessons forward into careers that spanned decades, they taught the next generation what they had been taught, and that generation taught the generation after.

Today, more than 50 years after four Australians stepped off a helicopter at NAB, American special operators still train in methods that trace directly to that moment, still apply principles that were revolutionary then, and remain devastatingly effective now, still honor a lineage that began with allies who had every reason to keep their secrets, but chose instead to share.

The forest ghosts are long retired now. Many have passed beyond reach of interview or recognition. The original training records remain partially classified and may never be fully released. The specific statistics will continue to be debated by historians who were not there and cannot fully understand what they are measuring.

But the legacy is beyond debate. It lives in every American special operator who has ever waited motionless while an enemy passed within touching distance. In every patrol that has moved through hostile territory without leaving trace of passage, in every ambush that materialized from empty terrain and dissolve back into nothing, the most terrifying weapon in Vietnam was not a gun. It was silence.

And the Australians taught America how to wield it.