November 1950, Capyong Valley, North Korea. The frozen ground crunched under every bootstep as Korean soldiers watched a new group of troops arrive at their position. These soldiers wore different uniforms. They had a red maple leaf on their shoulders. They were Canadians. The Korean soldiers had never fought beside Canadians before.

They did not know what to expect. The situation was bad. Very bad. Just weeks earlier, over 300,000 Chinese soldiers had crossed the Yaloo River. They came in waves that seemed to never end. Korean units were being crushed. Some battalions lost 60 men out of every hundred. Others lost 70 out of every hundred.

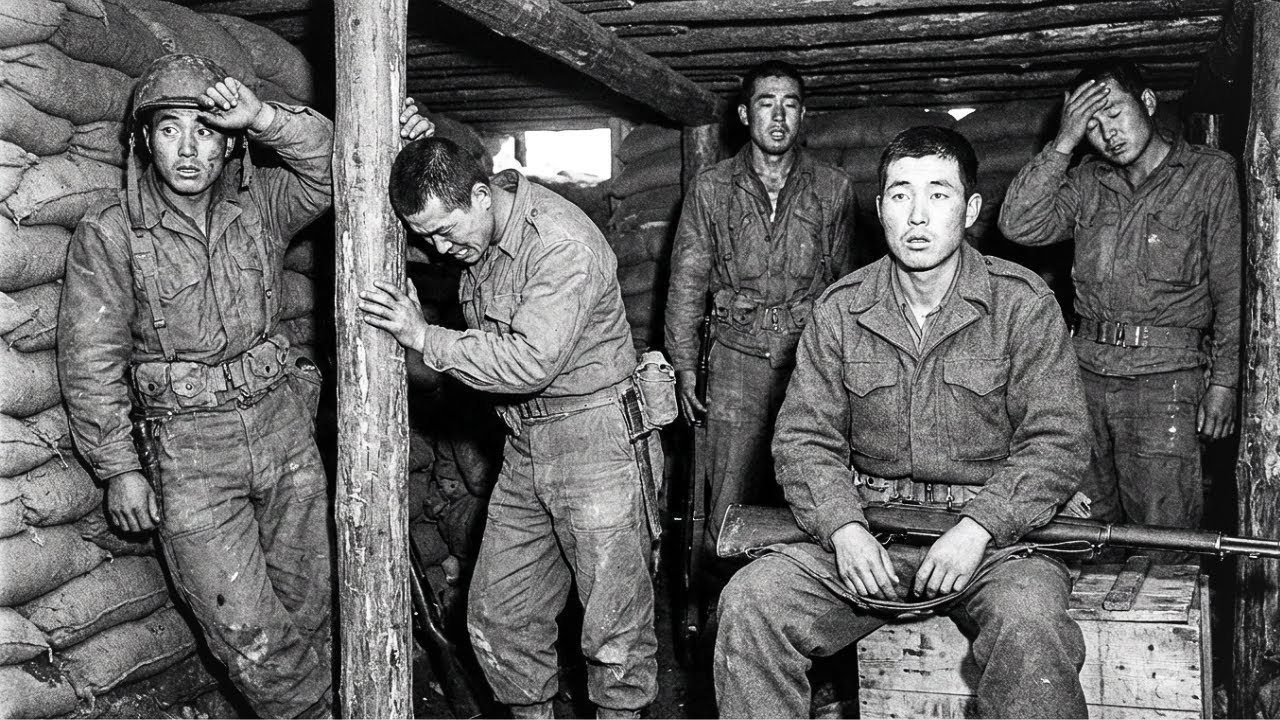

The defensive lines that had worked before were falling apart. Nothing seemed to stop the Chinese attacks. The temperature had dropped to 30° below zero. The cold bit through every layer of clothing. Soldiers could see their breath freeze in the air. Their fingers went numb while holding their rifles. At night, the wind howled across the valley like a living thing.

Men huddled in shallow holes dug into the hard earth, trying to stay warm enough to survive until morning. 700 Canadian soldiers from the second battalion, Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry, set up their position near the Korean troops. The Koreans watched them carefully. Most UN forces fought using mobile warfare.

They would shoot then pull back. They would retreat to better positions when the enemy got too close. That was the American way. That was what the Koreans expected these Canadians to do. But the Canadians did something strange. They started digging. They dug deep holes in the frozen ground. The sound of metal hitting ice and rock echoed through the valley.

The Korean soldiers looked at each other with confused faces. Why were these men digging so deep? Why were they not preparing to move quickly? A Korean liaison officer named Park watched the Canadians work. He had fought beside American units for months. He knew how they operated. These Canadians were different.

They smiled while they worked. They sang songs while digging in the frozen earth. They acted like they were building a home, not a fighting position. Park wrote in his report that night, “These soldiers do not act like they plan to retreat. They dig in deeper. The Chinese intelligence officers were getting reports about the new troops.

They read the reports and laughed. Minor Commonwealth force, they wrote. Not a threat. The Chinese had crushed larger forces. They had pushed back units three times the size of this Canadian battalion. 700 men meant nothing when you could send 20,000 soldiers in wave after wave. Korean soldiers who had survived earlier battles talked quietly among themselves.

They had seen what happened when Chinese forces attacked. The human wave attacks were terrifying. Hundreds of soldiers would charge at once. When the first wave fell, a second wave came right behind them, then a third, then a fourth. It did not matter how many bullets you fired. More soldiers always kept coming.

Most units broke and ran after the third or fourth wave. It was the smart thing to do. It kept you alive. Private Kim Sung-ho, a young Korean infantryman, sat in his position watching the Canadians. He had been fighting for 8 months. He had seen many UN soldiers come and go. The Canadians looked soft to him. They were polite. They said, “Please and thank you.

” when asking for supplies. They helped Korean civilians who walked past their positions. They shared their food rations with hungry children. Kim thought these men would not last long in real combat. Nice men did not survive this war. The Chinese were massing their forces just beyond the hills. Korean scouts reported seeing thousands of troops moving into position.

The attack would come soon, maybe tonight, maybe tomorrow. But it would come. It always came. A Canadian sergeant approached the Korean position. His name was Morrison. He spoke a few words of Korean, learned from a phrase book. He smiled and offered cigarettes to the Korean soldiers. Park, the liaison officer, accepted one, and lit it.

The warm smoke felt good in the frozen air. “You fight Chinese before?” Park asked in broken English. Morrison nodded. A few times we held our ground. You retreat when they come in big waves? Park asked. This was the important question. Every soldier needed to know if the men beside them would stand or run.

Morrison looked puzzled. Retreat. No, we dig in and hold. Park did not believe him. All soldiers said brave things before the fighting started. What mattered was what they did when thousands of enemy soldiers charged at their position, screaming and blowing bugles. That night, Korean soldiers heard something strange coming from the Canadian positions. Singing.

The Canadians were singing. Not war songs or angry songs. Happy songs. Songs about home. Songs about girls they loved. songs that made them laugh. The Korean soldiers looked at each other in the darkness. Who sang before a battle? Who acted happy when death was coming? Private Kim turned to his friend Lee.

Mittinom Deita, he whispered. They are crazy. Lee nodded. Crazy men die first. But there was something else in their voices, something they did not say out loud. The Canadians were not acting afraid. Every other unit showed fear before battle. Men got quiet. They checked their weapons over and over. They wrote last letters home.

The Canadians just kept digging, kept singing, kept smiling. It made no sense. Korean observer posts sent reports back to command. Canadian forces establishing defensive positions. They show no signs of preparing fallback routes. They have no vehicles positioned for quick retreat. Behavior is unusual. One report included a strange note.

A Korean sergeant had asked a Canadian private what they would do if the Chinese broke through their lines. The Canadian had laughed and said, “Then we will fight from the bottom of our holes until someone digs us out.” The Korean sergeant wrote, “They fight like they have nowhere to go, but they smile while doing it.

” The Canadians had a different way of fighting. Korean soldiers watched them prepare and saw something they had never seen before. The Canadians were not planning to move. They were planning to stay. Every action they took proved this. The trenches they dug were 1.8 m deep. That is about 6 ft. Deep enough for a man to stand in and still have protection.

Most soldiers dug holes just deep enough to crouch in. Shallow holes were faster to make. But shallow holes also meant you could leave quickly when things got bad. The Canadians dug like they were building fortresses. The ground was frozen solid. Every strike of the shovel rang out like hitting stone. Sparks flew when metal hit ice.

The men took turns digging. Their hands bled through their gloves, but they kept digging. They dug for two days straight. Korean soldiers stopped laughing at them. Anyone who worked that hard believed in what they were doing. The Canadian mortar teams did something very smart. They mapped out 47 different target spots around their position.

They wrote down the exact settings for each spot, how high to aim, how much powder to use, the distance to each target. They practiced firing at these spots during the day when they could see. At night, when the Chinese would attack, they would not need to see. They would already know exactly where to shoot. Each Canadian soldier carried more than 200 rounds of ammunition.

Most soldiers carried about 150 rounds. The extra 50 rounds added weight, heavy weight. But the Canadians wanted to be sure they would not run out of bullets when the fighting started. They also carried extra grenades, extra food, extra water, everything they needed to stay in their holes for a long time. The first real test came in late November.

Chinese scouts probed the Canadian lines. About 600 Chinese soldiers attacked one section of the Canadian position. The Koreans watched from their trenches nearby. They expected to see the Canadians fire and then pull back to a safer position. That was the normal thing to do when you were outnumbered 3 to one.

But the Canadians did not pull back. They waited. The Chinese soldiers got closer. 100 m away, 70 m, 50 m. Korean soldiers held their breath. Why were the Canadians not shooting? Had they frozen in fear? Then at 50 m, every Canadian rifle and machine gun opened fire at once. The sound was like thunder. The wall of bullets stopped the Chinese attack cold.

The enemy soldiers who survived turned and ran back. The Canadians had let them get close on purpose. At 50 m, every bullet hits its target. There is no wasting ammunition, no missed shots. When the smoke cleared, over 400 Chinese soldiers lay dead or wounded in front of the Canadian position. 23 Canadians were wounded. None were killed.

The Canadians had not moved back even one step. Private Kim, the Korean soldier, could not believe what he had seen. He turned to his friend Lee. “They let the enemy get that close on purpose,” he said. His voice shook. “They are either the bravest men I have ever seen or the craziest.” “That small battle taught the Chinese something.

The Canadians were not like other units, but the Chinese had thousands more soldiers. they would come back with bigger numbers. The real test came on April 24th, 1951. This was the Battle of Capyong. The Canadians held a hill called Hill 677. Intelligence reports said the 10th Battalion of the Chinese Army was coming.

About 5,000 Chinese soldiers against 700 Canadians. The math was simple and terrible. The attack started at night. The darkness was complete. No moon, no stars, just blackness. Then the Chinese bugles started blowing. The sound sent chills down every spine. The bugles meant the human waves were coming. Korean units nearby heard the bugles, too.

They knew what was coming next. Some Korean soldiers said prayers. Others checked their escape routes. When 5,000 soldiers attacked, the smart thing was to know which direction to run. But from the Canadian position, something strange happened. Between the bugle calls, the Koreans heard singing. The Canadians were singing.

Not loud war songs, quiet songs, songs from home. A Korean officer who heard it later said, “We heard them singing between attacks. It made no sense. Men about to die do not sing. The first Chinese wave hit the Canadian lines. The shooting was so loud it hurt to hear. Tracer bullets lit up the night like deadly fireflies.

The Canadians fired their weapons so fast that the gun barrels glowed red in the darkness. The first wave fell back. Then came the second wave. More shooting, more dead. The second wave fell back. The third wave came, the fourth, the fifth. For 14 hours straight, Chinese soldiers attacked Hill 677 in waves.

For 14 hours, the Canadians did not move back. The Canadian artillery fired 2,300 shells in those 14 hours. That is more than60 shells every hour. The ground shook like an earthquake. The noise was so loud that men’s ears bled. The smell of gunpowder was so thick you could taste it in your mouth. Five times, Chinese soldiers cut the telephone lines that connected the Canadians to their artillery support.

Five times, Canadian soldiers crawled out of their trenches under fire to fix the lines. The communication never stopped for more than a few minutes. The Canadians did something that shocked everyone. When Chinese soldiers got too close and started to overrun parts of their position, the Canadians called for artillery to fire on their own trenches.

They asked for shells to land right on top of them. They would rather risk dying from their own artillery than let the Chinese take the hill. A Korean officer watching from a nearby position saw this happen. He grabbed his radio and shouted to his command post. The words he used were mitum dita. It means they are crazy.

But then he added something else. But they are still there. When the smoke clears, the Canadians changed their firing positions every 20 minutes. They would shoot from one spot, then quickly move to another prepared spot. This kept the Chinese from figuring out exactly where they were. It also kept Chinese mortars from hitting them.

Even while being attacked by 5,000 soldiers, the Canadians stuck to their plan. They stayed calm. They stayed disciplined. Korean soldiers watching this battle learned something important that night. When you are outnumbered 7 to1, most armies break and run. But not these Canadians. They had made a choice before the first shot was fired and nothing would change their minds.

Hey, quick pause here. If you’re listening right now, help me prove something wrong. My mother said I wouldn’t even reach a th000 subscribers, but I believe stories like these deserve to be heard. And look where we’re at now, dreaming of a 100,000 subscribers. Help me show her that these videos matter.

Please subscribe to my channel, Canadians at War, and let’s keep breathing life into stories that were never meant to stay silent. Now, let’s continue. When the sun finally rose on April 25th, the results were clear and shocking. Hill 677 still belonged to the Canadians. Not one meter of ground had been lost. Not one single meter. The hill that 5,000 Chinese soldiers had attacked all night was still held by 700 Canadians.

The cost to the Chinese was terrible. Over 2,000 Chinese soldiers were dead or wounded in front of the Canadian positions. Bodies covered the hillside. The snow was red with blood. The survivors had retreated back beyond the hills. On the Canadian side, 10 men were dead. 23 were wounded. The difference in numbers told the whole story.

But the numbers told something else, too. If the Chinese had broken through Hill 677, they would have surrounded 60,000 United Nations troops. Those troops would have been cut off, trapped, and probably destroyed. 700 Canadians had saved 60,000 lives by refusing to move. Korean soldiers came to look at the Canadian positions after the battle.

They walked slowly through the trenches. They saw the empty shell casings piled waist high. They saw the machine gun barrels that had melted from firing so many bullets. They saw the walls of the trenches marked with bullet holes and shrapnel scars. They saw Canadian soldiers covered in dirt and blood calmly eating breakfast like nothing unusual had happened.

Private Kim stood at the edge of the Canadian position and looked down the hill. He could not count all the bodies. There were too many. He turned to a Canadian soldier sitting nearby. The soldier was eating canned beans straight from the tin. His hand shook from exhaustion, but he was smiling. “How?” Kim asked in English.

“How you not run?” the Canadian shrugged. “Where would we go? This is our hill. Korean soldiers began saying something to each other. The phrase spread from unit to unit. It means we retreated. They stayed. It was not said with shame. It was said with wonder. The Koreans had retreated because retreating kept you alive. The Canadians had stayed because staying was their job. Both choices made sense.

But only one choice won battles. Kim Songho, the young Korean private who had thought Canadians were soft, changed his mind completely. He later told a reporter, “I thought Canadians would be soft. They were polite off the battlefield, but devils on it.” Other Korean soldiers nodded when they heard this. Polite devils.

That described the Canadians perfectly. Something interesting started happening in the weeks after Capyong. Chinese prisoners were captured and questioned. Many of them said the same thing. Their commanders had given them orders to avoid any hill that flew the red maple leaf flag. The Canadian flag had become a warning sign.

It meant soldiers who would not retreat. It meant soldiers who would call fire down on their own heads rather than give up ground. Smart Chinese commanders told their men to find easier targets. The battle had happened at night in darkness and cold so complete you could not see your own hands. Korean observers who watched from nearby positions struggled to explain what it was like.

Gunpowder and smoke burned their noses and throats. The metallic taste of blood mixed with explosives stuck in their clothes for days. The vicer’s machine guns fired in bursts of 250 rounds, creating a continuous roar like a waterfall made of metal and death. When multiple guns fired together, orders had to be given with hand signals because no one could hear.

Tracer bullets lit up the darkness in streams of red and green light. Artillery shells turned night into day for brief moments. In those flashes, Korean soldiers saw waves of Chinese troops climbing the hill like ants covering the ground. And in the same light, they saw Canadians in their trenches, firing without stopping, without panic, without fear.

One thing surprised the Korean observers more than anything else. Between the waves of attacks, Canadian medics climbed out of their trenches. They went to help wounded Chinese soldiers. They gave them water. They bandaged their wounds. Then they went back to their trenches and shot at the next wave. This made no sense to the Koreans.

These were enemy soldiers. Why help them? A Canadian medic explained it simply. Wounded men are not soldiers anymore. They are just hurt people who need help. Even while under fire, Canadians shared their food rations with Korean civilians who were trapped near the battlefield. Old women and small children huddled in destroyed buildings.

Canadian soldiers would run through gunfire to bring them food and blankets. Then they would run back and continue fighting. Korean soldiers had never seen anything like it. The Korean military leaders paid attention to what happened at Capyong. They started studying how the Canadians had fought, the deep trenches, the pre-planned artillery targets.

The discipline of waiting until the enemy was close. These were not complicated ideas, but they worked. Korean units began adopting some of these methods. They dug deeper. They planned better. They learned that sometimes standing still was better than moving. The reputation of Commonwealth forces changed after Capyong. Before this battle, many commanders thought Commonwealth troops were good but not special.

After Capyong, Commonwealth forces were seen as immovable objects. If you put them on a hill and told them to hold it, that hill would not fall. Chinese strategy had to change. They could not just overwhelm Commonwealth positions with numbers anymore. They had to find ways around them. The Canadians earned 27 battle honors during the Korean War.

For a country their size, this was more honors per person than any other nation that fought in Korea. The soldiers who fought at Capyong received the United States Presidential Unit Citation. This award had only been given two times before in all of American history. It was the third time ever. That is how special the battle was.

The Korean War ended in 1953. The soldiers went home. But the memory of what happened on Hill 677 did not fade. It grew stronger with time. The lessons learned from those Canadian soldiers changed how people thought about warfare, courage, and what it means to stand your ground. The Canadian battalion that fought at Capyong kept the memory alive in a special way.

Every year on April 24th, they celebrate Capyong Day. It is not a party. It is a solemn ceremony. Old soldiers gather, some now in wheelchairs, some using canes. They remember the friends who died on that hill. They remember the 14 hours of fighting. They remember singing between the waves of attacks. For the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry, Capyong Day is as important as any national holiday.

It is the day their regiment proved what they were made of. In Korea, something remarkable happened. The Korean people did not forget either. Veterans who had fought alongside the Canadians told their children and grandchildren about what they witnessed. The story spread. In 2013, the South Korean government erected a memorial stone in Seoul.

The stone sits in a place of honor. The words carved into it tell the story of Hill 677. Korean school children visit this memorial on field trips. They learned that 700 foreign soldiers saved their country by refusing to retreat. Korean soldiers still visit the actual hill where the battle happened. They climb to the top and look down at the valley below.

They try to imagine what it was like that night. The darkness, the cold, the waves of enemy soldiers. The choice to stay or run. Standing on that hill, the choice to stay seems impossible. But the Canadians did it anyway. The military academy in Korea teaches the Battle of Capyong to every officer candidate. It is required study. Young Korean officers learn the tactics the Canadians used.

the deep defensive positions, the pre-planned fire zones, the discipline of holding fire until the enemy is close. But they also learned something else. They learned that technology and tactics only work if the soldiers using them have the courage to stand firm. No amount of training can replace the human decision to not run away.

Modern South Korean army defensive doctrine includes what they call the Capyong principles. These are the ideas the Canadians demonstrated on that frozen hill in 1951. Prepare your position completely. Know your fields of fire. Stay calm under pressure. Trust the soldiers next to you. Do not retreat unless ordered.

These principles are taught to every Korean soldier. The Canadians did not write them down in a book. They proved them with their actions. Every year, Canadian veterans of the Korean War travel back to Korea. Most of them are now over 90 years old. The trip is long and hard for men their age, but they make the journey anyway.

The Korean government treats them like heroes. News cameras follow them. School children line up to shake their hands. Korean veterans, now old men themselves, embraced the Canadians with tears in their eyes. These men shared something that cannot be explained to people who were not there. They shared the moment when courage mattered more than anything else.

In 2021, the 70th anniversary of the Battle of Capyong arrived. Only 23 Canadian veterans who fought in that battle were still alive. The Korean government sent representatives to Canada to honor each one personally. They brought medals. They brought letters from K Korean children thanking them. They brought soil from Hill 677 in small wooden boxes.

The veterans held these boxes and cried. That dirt was part of them. That hill was where they learned what they were capable of. The relationship between Canada and South Korea became uniquely strong because of the Korean War. Koreans call Canadians their blood brothers. This is not just a nice phrase. It means something real.

When Canadian tourists visit Korea, locals often refuse to let them pay for meals. Your grandfather saved our country, they say. This meal is nothing compared to that. Business deals between Canadian and Korean companies are built on trust that goes back to 1951. That trust was earned on a frozen hill when Canadians refused to abandon their Korean allies.

The lessons of Capyong apply to modern warfare, too. Today’s military leaders study asymmetric warfare. This means studying how smaller forces can defeat larger ones. Capyong is a perfect example. 700 men defeated 5,000 because of superior positioning, better discipline, and unbreakable will.

Modern special forces train using scenarios based on the battle of Capyong. The question is always the same. If you are outnumbered 7 to one, will you stand or run? Korean soldiers today have a saying cynada saw. It means fight like a Canadian soldier. This phrase is used when the situation is desperate. When retreat seems like the only option, when staying seems impossible.

The phrase reminds soldiers that impossible things have been done before. 700 Canadians proved it. The broader lesson of capyong goes beyond military tactics. It teaches something about human nature. We often make assumptions about people based on how they act in peaceful times. The Canadians were polite. They were friendly. They helped civilians.

They sang songs. From the outside, they did not look like fierce warriors. The Korean soldiers who first saw them thought they were soft. Even the Chinese commanders dismissed them as a minor threat. Everyone was wrong. The Canadians proved something the world needed to see. You can be gentle in peace and unbreakable in war.

These qualities come from the same source, knowing exactly who you are and what you stand for. What Korean soldiers said when they first fought Canadians started as surprise, even mockery, machinum dea. They are crazy. But by the end, those words meant something different. Crazy brave. Crazy loyal. Crazy enough to call artillery fire on their own position rather than surrender an inch of ground.

The Koreans learned that sometimes the quietest people make the loudest statements when it matters most. And on Hill 677 in April 1951, 700 Canadians made a statement that still echoes today. Courage is not about advancing. Sometimes courage is about refusing to take a single step back.