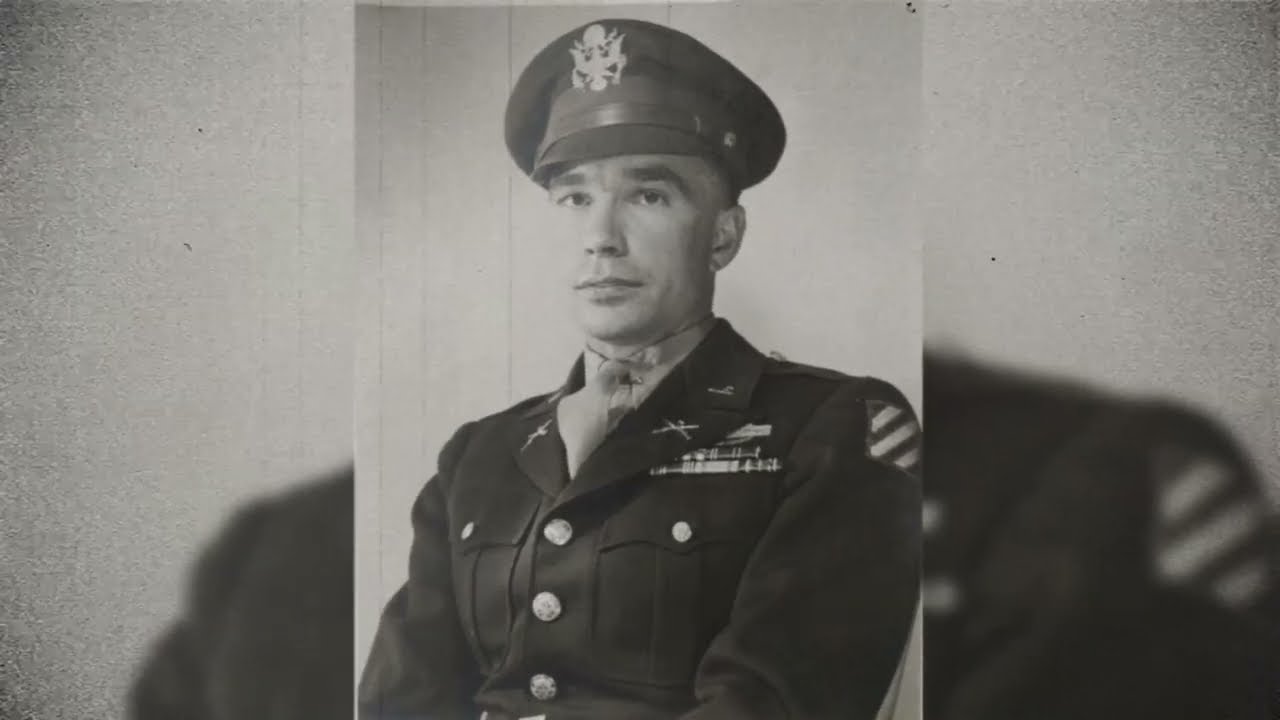

At 0700 on January 24th, 1945, First Lieutenant Garland Merl Connor stood in the frozen command post of Third Battalion, 7th Infantry Regiment, watching German artillery shells destroy the treeine 400 yardds to his front, 25 years old, intelligence officer, recently returned from the hospital with wounds still healing.

The German 19th Army had massed 600 infantry troops and six Mark 6 Tiger tanks for a counterattack designed to break through the American positions near Husen, France. Connor was 5’6, 120 lb. A tobacco farmer from Clinton County, Kentucky. He had never finished high school. The nearest school had been 15 miles from his family’s farm.

He had enlisted in March 1941. Four years of war, 10 major campaigns, four amphibious assault landings, wounded seven times. The last wound had sent him to the hospital three weeks ago. He had returned to his battalion 2 days earlier. Third battalion held a section of the front line north of the Kmar Pocket.

The Kmar Pocket was the last German- held territory in France, 850 square miles of frozen forest and farm fields west of the Ryan River. The Germans had held it since November. Every attempt to eliminate the pocket had failed. The French First Army had lost thousands of men trying to push the Germans back across the Rine. Operation Nordwind had started on New Year’s Day, the last major German offensive in the West.

Hitler had ordered Army Group G to break through American lines in Alsace. While the Battle of the Bulge still raged 300 m north, the offensive had failed, but the Germans in the Kmar pocket remained and they were desperate. Third battalion had been on the line for 18 days. Temperatures averaged 10° below zero. No moonlight. Snow covered everything.

Soldiers slept in frozen foxholes when they could sleep at all. German patrols probed the American positions every night. The battalion had lost 43 men in 2 weeks, mostly to artillery and sniper fire. Connor worked in the battalion command post. An intelligence officer gathered information about enemy movements, interrogated prisoners, analyzed patrol reports, marked German positions on maps. It was not a combat role.

Intelligence officers stayed behind the front line. They worked with maps and reports. They did not lead attacks. But Connor had not stayed behind the lines during four years of war. He had earned four silver stars for direct combat action. October 1943 in Italy. January 1944 at Anzio, September 1944 in France, February 1945.

Each silver star represented an action where Connor had risked his life to save other soldiers. He had a reputation in third battalion. When the situation turned desperate, Connor moved forward. At 0715, the German artillery barrage intensified. Shells walked across the battalion’s forward positions. Trees exploded.

Dirt and frozen earth fountained into the air. The barrage lasted 12 minutes. Then it stopped. Silence. Then the sound of tank engines. A runner burst into the command post. Germans advancing. Six Tigers. Infantry behind them. Hundreds of infantry moving through the woods toward the battalion’s left flank.

The battalion commander looked at the map. If the Tigers reached the American positions, they would roll through the foxholes. The battalion would be overrun. There were no American tanks in position to stop them. No tank destroyers. The only weapon that could stop six Tigers was artillery. But artillery needed a forward observer.

Someone who could see the Germans advancing. Someone who could adjust the fire. The forward observation post had been destroyed by the barrage. The observers were dead or wounded. No one could see the German advance from the command post. The trees blocked the view. If you want to see how Connor<unk>’s decision turned out, please hit that like button.

It helps us share more stories about forgotten heroes. Subscribe if you haven’t already. Back to Connor. Connor studied the map. The German advance was coming through a section of woods 400 yd from the command post. To observe the attack, someone would have to run 400 yd across open ground under German artillery fire, then stay in position ahead of the American line while six Tiger tanks and 600 German infantry advanced directly toward them.

Connor picked up a telephone and 400 yardds of wire. He looked at the battalion commander. Then he walked out of the command post into the snow. The German artillery barrage had stopped, but Connor knew it would resume. The Germans always fired preparation barges before tank attacks. They would wait for their infantry to get closer.

Then the guns would open up again to pin down the defenders while the Tigers rolled forward. Connor ran. 400 yardds of open ground between the command post and the front line. Snow covering frozen earth. The telephone wire unspooled behind him. He carried the spool in his left hand, the telephone handset in his right. His boots broke through the snow crust with each step.

At 100 yards, the German guns opened fire. Shells landed 40 yards to his left, then 30 yards to his right. The Germans were adjusting. They had observers watching the open ground. They could see a lone American soldier running toward their attack. A shell hit a tree 70 yard ahead. The tree exploded. Splinters and branches and frozen wood fragments showered down.

Connor kept running. Another shell landed 20 yard behind him. The concussion wave hit him like a fist. He stumbled but did not fall. The wire kept unspooling. At 250 yards, a shell destroyed a tree directly in his path. The trunk split down the middle. Half the tree crashed down across the snow.

Connor vaulted over the trunk without stopping. Shrapnel had torn through the branches. Pieces of hot metal hissed in the snow. Another shell, this one closer, 15 yards to his left. Frozen and snow geysered up. Chunks of dirt rain down on him. The blast wave hammered his eardrums. He could not hear his own breathing anymore, just a high-pitched ringing.

He reached the American front line at 300 yards. Soldiers crouched in foxholes. They stared at him. An intelligence officer running toward the German advance with a telephone. He did not stop to explain. He kept running forward toward the enemy. 30 yards beyond the American foxholes, Connor found what he needed. A shallow ditch, maybe 18 in deep.

Not deep enough to stop bullets, not deep enough to protect against artillery, but deep enough to give him a sight line toward the German advance while keeping his silhouette below the snow level. He dropped into the ditch. The telephone wire had held. He cranked the handset. The connection buzzed. Then a voice.

The artillery fire direction center 3 miles behind the front line. American 105mm howitzers, 12 guns. Enough firepower to shatter a German attack if the shells landed in the right place. Connor gave his position. The fire direction officer confirmed. Connor was now the eyes of third battalion’s artillery.

Everything depended on what he could see and whether he could stay alive long enough to direct the guns. He raised his head above the ditch rim. The German infantry were 200 yd away, moving through the trees in squad formations, rifles at the ready. They advanced in short rushes. One squad would move while another provided covering fire.

Professional soldiers, experienced, they knew how to attack through defended positions. Behind the infantry, the Tigers. Connor could see four of them. Massive 60-tonon monsters pushing through the smaller trees like they were saplings. The tigers stayed in the treeine, using the forest for cover, but they were coming. Slow, methodical, they would break into the open ground in minutes.

The German infantry had not seen him yet. He was alone 30 yards ahead of the American line in a ditch that provided almost no protection with a telephone and 600 German soldiers walking directly toward him. Connor lifted the handset. He gave the coordinates. Fire mission. Enemy infantry in the open. 600 m. Adjusting. The first shells would arrive in 40 seconds.

If the Germans spotted him before the shells landed, they would kill him before he could adjust the fire. If the shells landed too close to his position, they would kill him anyway. If the shells landed too far from the German advance, the attack would continue and 600 Germans would overrun third battalion’s positions. Connor watched the Germans advance.

He counted the seconds. 38 39 40. The sky screamed. 12 105 mm shells hit the treeine 150 yards behind the German infantry. Too far. Connor grabbed the handset. Drop 100. Fire for effect. The German infantry kept advancing. They had not reacted to the shells. Artillery landing behind an advance was normal.

It meant the defenders were guessing. The Germans knew they had time before the Americans adjusted their fire. But Connor was not guessing. He could see every German soldier, every movement, every squad leader signaling his men forward. The second salvo arrived 18 seconds later. This time the shells landed in the middle of the German formation.

The forest erupted. Trees disintegrated. Shrapnel screamed through the air in every direction. The 105 shells carried 14 lbs of high explosive each. 12 shells, 168 pounds of explosive detonating simultaneously among 600 men packed into attack formations. German soldiers disappeared. Others went down. The advance stopped.

Connor cranked the handset. Repeat fire. Same coordinates. Another salvo. Then another. The American guns were firing for effect now. Maximum rate of fire. Four rounds per minute per gun. 48 shells every 60 seconds hammering the same 200 square yards of forest. The German infantry scattered. Squad formations broke apart. Soldiers ran for cover.

Some dove behind trees. Others tried to crawl away from the impact zone. The forest had become a killing ground. But the tigers were still coming. Connor could see all six now. They had broken out of the treeine into open ground. The artillery had not touched them. 105 shells could damage a Tiger’s tracks or optics, but they could not penetrate the armor.

The Tigers needed direct hits, multiple direct hits, and even then the shells might bounce off. The tanks advanced in a wedge formation, two in front, two behind them, two more bringing up the rear. Tank commanders stood in the turrets. They were scanning for targets, looking for American positions to engage. One of the Tigers fired.

The 88mm gun cracked like thunder. The shell hit an American foxhole 300 yd to Connor<unk>s right. Dirt and snow exploded upward. The soldiers in that foxhole were dead. Another Tiger fired. Another foxhole obliterated. The Tigers were 300 yd from the American line. In 4 minutes, they would reach the foxholes. Once they crossed the defensive line, third battalion would collapse.

Tigers in the rear of American positions meant panic. route. Hundreds of soldiers running. The Germans would pursue. They would slaughter the retreating Americans. Then they would push deeper into the sixth army group sector. The entire front could collapse. Connor shifted his fire mission. Enemy armor advancing. 250 m.

Adjust fire onto the tanks. The problem was precision. Artillery was not designed to kill tanks. Artillery saturated areas. It killed infantry in the open. It destroyed buildings. It cut communication lines, but tanks were small targets, fast targets, armored targets. The shells started falling around the Tigers.

One shell landed 10 yards in front of the lead Tiger. The tank drove through the blast. Another shell hit behind the formation. The Tigers kept coming. Their commanders knew American 105s could not stop them. They would drive through the artillery and into the American positions. Connor needed the shells closer. Drop 50. Fire for effect.

The next salvo landed among the Tigers. A shell hit the lead tank’s right track. The track broke. The Tiger slew hard right and stopped. Immobilized, but still dangerous. The turret traversed. The 88 mm gun was still operational. Another Tiger took a shell on the engine deck. Smoke began pouring from the rear of the tank. The crew might abandon it or they might keep fighting.

A disabled Tiger with a working gun was still a fortress. Four Tigers were still advancing and they had adjusted their course. They were moving toward Connor<unk>’s position. The tank commanders had spotted his muzzle flashes. They had seen the telephone wire. They knew someone was directing the American artillery. And they were coming to kill him.

Connor checked the ditch. 18 in of cover. Not enough to stop an 88 mm shell. Not enough to stop machine gun fire. Not enough to stop anything a Tiger tank could throw at him. The Germans were 150 yd away now. Close enough that Connor could see the Balkan crews markings on the turrets. Close enough to see the tank commander’s faces.

He lifted the handset one more time. Fire on my position. The fire direction officer repeated the coordinates back to him. Connor confirmed. The officer asked him to confirm again. Calling artillery fire on your own position was not standard procedure. It meant friendly shells would land within yards of the observer.

It meant the observer might die. Connor confirmed a third time. 40 seconds later, the first shells landed 30 yard in front of his ditch. The concussion wave felt like being hit by a truck. The air pressure changed. His lungs compressed. His vision blurred. Frozen dirt and shrapnel screamed overhead. The sound was beyond thunder. It was the sound of the world ending.

He stayed in the ditch. He kept the handset pressed to his ear. Drop 20. Repeat fire. The next salvo landed 20 yards out. Close enough that he could feel the heat from the explosions. Close enough that shrapnel tore through the air 6 ft above his head. If he stood up, he would be shredded.

If the shells landed 10 yards closer, the ditch would not save him. The Tigers had stopped advancing. The tank commanders had buttoned up, closed their hatches. The artillery was landing too close. Even a Tiger crew did not want to be outside their armor when American shells were detonating at point blank range.

But the German infantry was rallying. Connor could see them forming up again. Company strength formation. Maybe 200 soldiers who had survived the initial barrage. They were using the Tigers for cover. Staying behind the massive tanks. Moving when the tanks moved, using the armor as mobile fortresses. The attack was continuing. Connor adjusted fire.

He walked the shells back and forth across the German advance. Every time a group of infantry tried to move forward, he dropped shells on them. Every time the Tigers advanced, he called fire directly in front of them. One Tiger took a direct hit on the turret. The shell did not penetrate, but the impact damaged the turret ring.

The turret would not traverse anymore. The tank could only fire straight ahead, effectively useless. Another Tiger lost its second track. Two broken tracks meant the tank could not move. The crew abandoned it. Five men scrambled out of the hatches and ran back toward the German lines. American machine gun fire from the foxholes cut two of them down.

The other three disappeared into the tree line. Three Tigers remained operational and the German infantry was getting closer. Connor could see individual faces now 100 yards away. German soldiers crawling through the snow using shell craters for cover, moving in small groups. They were trying to flank his position.

If they got around him, they could cut the telephone wire. Once the wire was cut, the artillery would stop. The attack would succeed. The temperature was 10° below zero. Connor had been lying in the ditch for 40 minutes. His hands were numb. His feet were numb. Every time a shell landed close, frozen dirt rained down on him. It got in his eyes, in his mouth.

The handset was slippery with ice, but he kept calling fire. A shell landed 15 yd to his right, then another 15 yd to his left. The Germans had him bracketed. Their artillery observers had pinpointed his position. They were trying to kill him with counter battery fire. German shells and American shells were landing in the same 100yard radius.

The ditch had become the focal point of two artillery bargages. Soldiers in third battalion’s foxholes could see what was happening. A lone lieutenant lying in a ditch ahead of the American line, calling artillery on his own position. German shells trying to kill him. American shells landing so close that fragments were hitting the edge of his ditch. And he was not moving.

He was not running. He was staying in place, adjusting fire, killing Germans. The German infantry pushed forward again, 80 yards away now. Close enough that Connor could hear their officers shouting commands. Close enough to hear the bolt actions on their Mouser rifles. He dropped the artillery another 10 yard. The shells landed between him and the advancing Germans.

60 yard from his position. The blast waves hammered him. Dirt cascaded into the ditch. Something hit his left shoulder. Shrapnel or a rock? He could not tell. His shoulder went numb. He switched the handset to his right hand. The German advance stopped again, but they were not retreating. They were finding cover waiting.

They knew the American artillery observer had to be close. They knew if they could locate him, they could kill him. And once he was dead, nothing would stop them. The three remaining Tigers began advancing again. They had spread out 50 yards between each tank, making themselves harder targets. They were 200 yd from the American foxholes.

Now Connor called fire on the leftmost Tiger, then the center tiger, then the right. He was splitting the artillery between all three targets, trying to damage tracks, trying to damage optics, trying to slow them down. One shell hit the center Tiger’s front glacus plate. The armor held, but the impact rocked the 60-tonon tank backward.

The driver lost control momentarily. The Tiger slewed left. Its track caught on a frozen stump. The track jammed. Two Tigers still advancing and the German infantry was inside 50 yards. The German officer leading the infantry advance was 30 yards from Connor<unk>’s ditch. He could see the officer’s face. Young, maybe 22 years old, probably a lieutenant.

The officer was signaling his men forward with hand gestures. No shouting now. They were too close. Sound would give away their exact positions. 20 German soldiers were following the officer, crawling through the snow, rifles ready. They were moving in a skirmish line, trying to overwhelm Connor<unk>’s position from multiple angles simultaneously.

Connor cranked the handset. He gave new coordinates. Drop five. Fire for effect. The shells landed 25 yards in front of him. The German officer disappeared in the explosion. So did four of his soldiers. The others went flat, pressed themselves into the snow, waited for the barrage to pass.

But Connor did not let the barrage pass. He kept the shells falling, adjusted left, adjusted right, created a wall of explosions between himself and the German infantry. The shells were landing so close now that he could feel the heat on his face. Hot metal fragments were hitting the edge of the ditch.

Some fragments were landing inside the ditch. One piece of shrapnel embedded itself in the frozen earth 2 in from his right hand. The two remaining Tigers had closed to 150 yards from the American foxholes. Close enough to use their machine guns effectively. The bow gunners opened fire. Sustained bursts from the MG34 machine guns.

792 rounds per minute. The bullets tore through the tree line, chewed through logs, kicked up snow and dirt around the American positions. Soldiers in the foxholes returned fire, but rifle bullets could not hurt a tiger. The American machine gunners tried to hit the Tiger’s vision ports, hoping to blind the drivers, hoping to force the tanks to button up completely and slow their advance.

It was not working. The Tigers kept rolling forward. Connor shifted fire back to the tanks. He called for smoke shells mixed with high explosive. The smoke would obscure the Tiger’s vision, make it harder for the tank commanders to spot targets. The high explosive would continue to damage tracks and optics. The artillery battery complied.

Smoke shells and H shells began landing around the Tigers. White phosphorous smoke billowed up, thick, choking. The Tigers disappeared into the smoke cloud, but they were still coming. Connor could hear the engines, hear the tracks grinding through frozen earth. The smoke had not stopped them. It had only made them invisible.

A Tiger emerged from the smoke cloud. 70 yardd from the foxholes. The 88 mm gun fired. An American machine gun position exploded. Three soldiers dead. Connor called fire directly on the Tiger. Danger close. He specified the exact coordinates. The fire direction officer hesitated. Those coordinates were within 50 yard of Connor<unk>’s position.

The shrapnel radius of a 105 shell was 50 yard. Connor would be inside the kill zone. Connor repeated the coordinates. The shells landed. One shell hit 10 yard behind the Tiger. Another hit 15 yd to the left. A third shell landed directly in front of the tank. The explosion tore into the Tiger’s front hull. The driver’s vision port shattered.

The tank swerved hard right. The driver was blind. The Tiger crashed into a crater and stopped. The crew tried to back out. The tracks spun. The tank was stuck. One Tiger remained and the German infantry had regrouped. They were advancing again. This time from a different angle, using the smoke for cover. Connor could not see them.

He could only hear them. Voices in the smoke. Boots crunching through snow. The metallic click of rifle bolts. He estimated their position and called fire. The shells landed in the smoke. He could not see the results. He adjusted based on sound. When he heard voices to his left, he shifted fire left. When he heard movement to his right, he shifted fire right.

The artillery battery was running low on ammunition. The fire direction officer reported they had maybe 15 minutes of sustained fire remaining. After that, they would need to pause to reload. 15 minutes without artillery support. The Germans would use that window to overwhelm the American positions. Connor had been in the ditch for 1 hour and 20 minutes.

His assistant had joined him 40 minutes ago. A private from the battalion intelligence section. The private had low crawled from the American foxholes with extra telephone wire and a backup handset. The private was lying 5 ft to Connor<unk>’s right, watching for German infantry, calling out positions.

The private spotted movement 15 yards, German soldiers coming through the smoke. Connor called the coordinates. The shells landed 12 yards out. The concussion wave lifted both men off the bottom of the ditch. Dirt and ice and shrapnel filled the air. Something hit the private. The private screamed. Shrapnel had torn through his left leg.

Blood poured into the snow. Connor grabbed the private and pulled him deeper into the ditch. The private was still conscious, still alive, but he needed a medic. Needed evacuation. The private refused to leave. He stayed in the ditch, kept watching for Germans. His leg was bleeding, but he could still see, still call positions.

The last Tiger was 60 yards from the American line now, and German soldiers were inside 10 yards of Connor<unk>’s position. Connor dropped artillery 5 yd in front of his ditch. The shells landed closer than any previous fire mission. The blast lifted him completely off the ground. His body slammed back into the frozen earth. His ears went deaf.

Complete silence. Then the ringing started, high-pitched, constant, drowning out every other sound. But the German soldiers who had been 10 yards away were gone. He cranked the handset. His hands were shaking. From cold or shock or exhaustion, he could not tell anymore. The fire direction officer’s voice came through the handset.

faint, distant, like the officer was speaking from another world. Connor adjusted fire back onto the last Tiger. The tank was 40 yards from the American foxholes now. Close enough that its machine guns could suppress every defensive position. Close enough that its main gun could destroy foxholes one by one at point blank range.

The Tiger’s turret was traversing, looking for targets. The tank commander had his hatch open again. He was standing in the turret scanning the American line, choosing which position to destroy first. Connor gave the coordinates, requested high explosive, maximum concentration. Every gun the battery could bring to bear on a single target.

12 shells arrived simultaneously. The Tiger disappeared in a storm of explosions. When the smoke cleared, the tank was still there, still intact. The armor had held, but the tank was not moving. The driver’s vision blocks were gone, shattered by shrapnel. The tank commander had dropped into the turret and slammed the hatch.

The Tiger was blind and immobile. The crew abandoned the vehicle. Five men scrambled out. They ran toward the treeine. American rifles fired from the foxholes. Three German tankers went down. Two made it to cover. All six Tigers were destroyed or abandoned. The German armor assault had failed, but the infantry was still fighting.

Companies worth of German soldiers were scattered across 300 yards of forest and field. They had taken massive casualties, at least 150 dead, maybe 200. But 400 soldiers remained, and they were veterans. They knew how to fight without tank support. They knew how to use terrain, how to find cover, how to advance under artillery fire.

Connor shifted the barrage back to the infantry positions. He walked shells across the tree line where the Germans had taken cover, then across the shell craters where small groups were hiding, then across the approaches where reinforcements might advance. The fire direction officer reported 10 minutes of ammunition remaining.

The battalion commander came on the radio net. He ordered Connor to withdraw, fall back to the American line. The artillery would lay down covering fire. Connor could make it back to the foxholes. Connor stayed in the ditch. From his position, he could see the entire German formation. Could see every attempted rally, every movement, every attempt to reform for another assault.

If he withdrew, the Americans would lose their forward observer. The artillery would fire blind. The Germans would exploit the gap. They would mass for one final push, and without accurate artillery fire, that push might succeed. The wounded private was still beside him, still conscious. The private’s leg had stopped bleeding.

The cold had frozen the wound. The private kept his rifle ready, watching the approaches. If German soldiers rushed the ditch, the private would fight. Two hours had passed since Connor had left the command post. German artillery began falling again. The German observers had finally pinpointed Connor<unk>s exact position. Shells landed 20 yard behind the ditch, then 15 yard, then 10 yard.

The Germans were walking their fire toward him methodically, professionally. In another minute, the shells would land directly on the ditch. Connor called counter battery fire. He gave the coordinates of the German artillery positions. The American guns shifted targets, began firing on the German howitzers 3 mi behind the German front line.

The German artillery fire slackened, then stopped. The counter battery fire was working. The German gun crews were taking cover or dying. Connor shifted fire back to the German infantry. The sun had risen higher. Full daylight now. The Germans could see how many of them had died. Could see the destroyed tigers. could see the cratered forest, could see one American lieutenant lying in a shallow ditch with a telephone.

One man calling down thunder. A German squad tried one more time. Eight soldiers. They came from the left running, trying to close the distance before Connor could adjust fire. They were 70 yards away when they broke cover. They made it 40 yard before the shells arrived. The squad disappeared. The explosions threw bodies into the air.

No more German soldiers tried to advance. The fire direction officer reported 5 minutes of ammunition remaining. Then the guns would go silent, but the German attack had stalled. The surviving German soldiers were pulling back, moving away from the kill zone, dragging wounded comrades with them, leaving their dead behind. Connor kept the shells falling, pursued the retreating Germans.

made sure they kept running, made sure they did not reform, made sure they understood that trying to attack third battalion’s positions again would mean death. 3 hours after Connor had picked up the telephone and walked out of the command post, the German counterattack was over. Connor stayed in the ditch another 20 minutes, watching, making sure the Germans were not regrouping, making sure no follow-up attack was coming.

The telephone handset was silent. The artillery battery had ceased fire. The guns needed to reload, needed to cool, needed to prepare for the next emergency. The battlefield was quiet. No engine sounds, no rifle fire, no explosions, just wind moving through shattered trees and the sound of wounded men calling for help.

German voices, faint, distant, coming from the treeine 300 yd away. Connor finally stood up. His legs barely held him. Two hours lying in frozen earth. His muscles had locked. His joints refused to bend. He took one step, then another. The wounded private tried to stand, could not. Connor helped him up, supported his weight.

They began walking back toward the American line. Soldiers emerged from the foxholes. They stared at Connor at the ditch where he had been lying, at the cratered ground between the ditch and the German positions. The Earth looked like the surface of the moon. Shell craters overlapping shell craters. Destroyed equipment. Pieces of tigers scattered across 200 yards. Bodies.

The battalion commander met Connor at the foxhole line. The commander looked at the battlefield, looked at Connor, did not speak, just nodded. Medics took the wounded private to the aid station. The private would survive. The leg wound was clean. No broken bones. He would be back with the battalion in 6 weeks.

Connor walked to the command post. His shoulder was still numb. Something had hit him. He could not remember when. During the third hour, maybe the fourth. A medic examined the shoulder. Shrapnel, small piece embedded just below the skin. The medic removed it, bandaged the wound, told Connor he was lucky. The intelligence section went forward after the German retreat.

They counted bodies, counted destroyed equipment, made notes for the afteraction report. 53 German soldiers confirmed dead, another 78 wounded left behind when the Germans withdrew. The actual German casualties were higher. The Germans had dragged many of their dead and wounded back to their own lines during the retreat. Estimates put total German losses at over 150 killed and wounded.

All six Tiger tanks destroyed or abandoned, four immobilized by artillery damage, two abandoned after catastrophic track failures. American recovery teams would salvage the Tigers later, strip them for intelligence, examine the armor, study the fire control systems. Third battalion had lost 11 soldiers killed, 23 wounded.

Most of the casualties had occurred before Connor reached the ditch. During the initial German artillery barrage, the Tigers had killed three more Americans before their destruction. After Connor began directing artillery, American casualties had stopped. The battalion remained on the line for another 8 days. The Germans did not attack again.

They had lost too many men, too many tanks. The Kmar pocket offensive was over. The 19th Army would spend the next two weeks trying to hold their positions while the French first army prepared for the final push. On February 10th, 1945, Lieutenant General Alexander Patch presented Connor with the Distinguished Service Cross.

Patch was the commander of seventh army. He had come to third battalion specifically to present the award. The citation read, “Extraordinary heroism during the German counterattack on January 24th. It detailed Connor<unk>s advance under fire, his 3 hours directing artillery from an exposed position, his decision to call fire on his own position when the Germans closed to within yards.

The battalion commander had recommended Connor for the Medal of Honor. The paperwork had gone up through division, through core, through army, but the award timeline was too slow. Connor was being sent home. He had been in combat for 28 consecutive months. He had been wounded seven times. The army was rotating him back to the United States.

On March 15th, Connor left France. He sailed from LAV on a transport ship. Arrived in New York 3 weeks later. He was honorably discharged on June 22nd, 1945. The war in Europe ended May 8th. Connor was already home, already trying to forget. Albany, Kentucky held a parade for him in May. The town honored their returning soldier.

Alvin York spoke at the ceremony. York was the most famous Medal of Honor recipient from World War I. He had come from Palm Mall, Tennessee, 50 mi from Albany. York understood what Connor had done, understood the weight of it. Connor met a woman at the parade, Pauline Wells. She was 20 years old. She had heard the stories about Connor<unk>’s service, had heard the medal citations read aloud during the ceremony.

She could not believe the stories, could not believe that the quiet 5’6 farmer standing in front of her had done what the officers described. Connor did not talk about the war. When people asked, he said he had left those memories across the Atlantic Ocean. He would not bring them home. He married Pauline on July 9th, 1945.

They lived on Indian Creek, several miles north of Albany, a farm with no electricity, no running water. They worked the land with mules and horses, tobacco, corn, the same crops Connor<unk>s family had grown for generations. In 1950, the government bought their property. Lake Cumberland was being created.

The reservoir would flood their farm. They moved to the Roland community in southeastern Clinton County. Started again. New land, new crops, same life. Connor became president of the Clinton County Farm Bureau, held the position for 17 years. He helped other farmers, advised them on crop rotation, on soil conservation, on dealing with the agricultural bureaucracy.

He was active in veterans organizations, paralyzed veterans of America, disabled American veterans. He traveled to nearby counties helping veterans file claims for benefits. He never talked about January 24th, 1945. Pauline asked him once early in their marriage what had happened in France. What had he done to earn all those medals? Connor looked at her, said he had done what needed to be done.

That was all there was to it. He would not elaborate. The medals stayed in a cardboard box inside a duffel bag in the back of the living room closet. Pauline knew they were there. She had seen them once. The distinguished service cross, four silver stars, bronze star, purple hearts, the French quad deare, but Connor never displayed them, never mentioned them, never wore them.

53 years passed. In 1996, a veteran named Richard Chilton wrote to the Connor home. Chilton was researching his uncle, Private Gordon Roberts. Roberts had been killed at Anzio in January 1944. Chilton had learned that Robert served with Connor. He wanted to know if Connor remembered anything about his uncle’s final days.

Connor invited Chilton to visit. They sat in the living room. Connor was 77 years old, diabetic, kidney failure. He had maybe 2 years left. Connor told Chilton about Anzio, about Roberts. Connor had carried Roberts to a medical aid station after Roberts was hit, had stayed with him until he died. As Connor spoke, he began to cry.

52 years later, and the memory still broke him. Pauline suggested Chilton looked through Connor<unk>s military records. Maybe there would be information about Roberts. She brought out the duffel bag, the cardboard box. Chilton opened it, saw the medals, read the citations. His hands started shaking. He looked at Connor, then at Pauline, said one sentence.

This man should have been awarded the Medal of Honor. Chilton began the process, filed paperwork with the Army Board for Correction of Military Records, gathered eyewitness statements from men who had served with Connor, built a case for upgrading the Distinguished Service Cross. The board rejected the application in 1997, rejected an appeal in 2000. Connor died November 5th, 1998.

He was 79 years old. He was buried in Memorial Hill Cemetery in Albany. The Distinguished Service Cross went with him. But Pauline did not stop. She collected more eyewitness accounts, found three soldiers who had been in the foxholes on January 24th, who had watched Connor in that ditch for 3 hours, who had seen what he did.

She resubmitted the case in 2008. Nothing happened. Historians supported the upgrade. authors, lawmakers. Steven Ambrose wrote about Connor in 2000, called his actions far above the call of duty. The Rhode Island Senate passed a resolution in 2005 calling for the Medal of Honor. Seven retired generals endorsed the application. Still nothing.

In 2014, Pauline sued the Army in federal court. A judge ruled she had waited too long. She appealed to the Sixth Circuit Court. The case went to mediation. During the proceedings, the government attorney broke down crying. Her father had served in third battalion, had been wounded January 25th, one day after Connor<unk>’s action.

She said Connor might have saved her father’s life. The Army board finally recommended the upgrade in 2015. Congress passed legislation waving the time limit. On March 29th, 2018, the White House announced the award. On June 26th, President Trump presented the Medal of Honor to Pauline in the East Room. She was 89 years old. It had been 22 years since Chilton opened that cardboard box.

20 years since Connor died. The citation was read aloud. First Lieutenant Garland Merl Connor distinguished himself by acts of gallantry and intrepidity. Volunteered to run 400 yardds through enemy fire. directed artillery for three hours from an exposed position, called fire on his own position, killed 50 Germans, stopped six Tiger tanks, saved his battalion.

Pauline held the medal, the medal her husband had never sought, had never mentioned, had left in a box for 50 years because he thought talking about it would be bragging. The second most decorated soldier of World War II after Audi Murphy, and almost no one knew his name. If this story moved you the way it moved us, do me a favor.

Hit that like button. Every single like tells YouTube to show this story to more people. Hit subscribe and turn on notifications. We’re rescuing forgotten stories from dusty archives every single day. Stories about soldiers who save battalions with telephone wire and courage. Real people, real heroism.

Drop a comment right now and tell us where you’re watching from. Are you watching from the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, Australia? Our community stretches across the entire world. You’re not just a viewer. You’re part of keeping these memories alive. Tell us your location. Tell us if someone in your family served.

Just let us know you’re here. Thank you for watching and thank you for making sure Garland Merl Connor doesn’t disappear into silence. These men deserve to be remembered, and you’re helping make that