At 14:30 on February 2nd, 1945, Corporal Clarence Jenkins crouched in the gunner’s seat of an M4 A3 Sherman tank, watching death roll toward him on steel tracks. He was sitting inside a 30-tonon box of steel, nicknamed the sledgehammer, parked on a narrow dirt trail in the Villa Verde Mountains of Luzon.

The jungle outside was a green wall so thick it blocked out the sun, trapping the humidity until the air felt like hot soup. Inside the tank, the temperature was hovering around 110°. It smelled of old sweat, diesel fumes, and the metallic tang of fear. Jenkins wasn’t looking at the trees. He was looking through his M4 periscope, staring at a blind corner in the trail 70 yard ahead.

And around that corner came the nightmare. First came the sound. It was a high-pitched mechanical squeal, the sound of unlubricated metal grinding on rock. Then came the exhaust smoke, blue and oily, drifting through the ferns. And then one by one, they appeared. Japanese type 97 Kaiha tanks. They were smaller than the Sherman, painted in jagged camouflage patterns of brown and green.

They looked like mechanical beetles scuttling out of the undergrowth. 1 2 3. They kept coming until the trail was choked with them. Eight enemy tanks. They stopped in a line, engines idling, their 47 mm cannons swinging toward the lone American tank blocking their path. Jenkins sat perfectly still. His hand rested on the brass elevation wheel of his 75mm main gun.

His foot hovered over the firing pedal. In any other tank crew in the United States Army, the gunner would have already fired. The doctrine was simple. He who shoots first lives. Speed was life. Hesitation was death. But Jenkins didn’t fire. He watched the lead Japanese tank commander pop his hatch and looked through binoculars.

He watched the turret of the second enemy tank rotate 3° to the left. He watched the leaves shaking on the trees from the vibration of the engines. He was waiting. And because he was waiting, the rest of his crew was screaming. The tank commander, a nervous sergeant named Miller from New Jersey, was yelling orders that echoed off the steel walls of the turret.

He shouted for the driver to reverse. He shouted for the loader to clear the breach. He screamed at Jenkins to shoot. The driver, a kid named Kowalsski, slammed the Sherman into reverse, but the gears just ground against each other with a sickening crunch. They were stuck. The heavy rains had turned the trail into a mud pit, and the Sherman had sunk to its axles. They couldn’t move backward.

They couldn’t turn around. They were a stationary target sitting in the middle of a shooting gallery. The panic inside the tank was absolute. It was the kind of panic that turns trained soldiers into terrified animals. They knew the math. The Japanese Type 97 wasn’t a heavy tank, but it carried a high velocity gun that could punch through the side armor of a Sherman like it was made of cardboard.

And there were eight of them. If they all fired at once, the sledgehammer wouldn’t just be destroyed, it would be vaporized. The crew looked at Jenkins. They looked at his back curved over the gun’s sight. They looked at his hand, which hadn’t moved. They hated him in that moment. They hated him because of his nickname.

They hated him because he was tick- tock. The nickname had started six months ago at the training grounds in California. It wasn’t a compliment. In a unit that prided itself on lightning fast reflexes, Jenkins was an anomaly. He was a farm boy from Oklahoma who moved with a maddening deliberate slowness.

He walked slow, he talked slow, and worst of all, he shot slow. On the gunnery range, the instructors taught the snapshot. You saw the target, you laid the gun and you fired. 2 seconds, 3 seconds max. It was about volume of fire. Suppress the enemy, get rounds down range. Jenkins didn’t shoot like that. When a target popped up, Jenkins would freeze.

He would peer through the site. He would make a tiny adjustment to the elevation. Then he would make a tiny adjustment to the traverse. Then he would wait another heartbeat, letting the tank settle on its suspension. The instructors would scream at him. They would bang on the turret with wrenches. They would call him a corpse.

They timed him with a stopwatch. 5 seconds. 6 seconds. 7 seconds. In tank warfare, 7 seconds is a lifetime. It is enough time for an enemy shell to travel three miles. The other crews mocked him relentlessly. They called him tick- tock Jenkins. They made bets on whether he would fire before the war ended.

They drew cartoons of him with a spiderweb growing on his gun barrel. One lieutenant told him to his face that he was a liability, that his hesitation would get good men killed. They tried to transfer him to a supply truck, but the battalion was short on gunners. So, he stayed. He stayed and he took the abuse. He never argued.

He never tried to explain that he wasn’t freezing. He was calculating. He wasn’t painting a picture. He was doing geometry in his head. He knew that a 75 mm shell had a specific arc. He knew that if you hit a tank on the thickest part of its armor, the shell would just bounce off with a harmless clang. You had to hit the weak spots, the vision slits, the turret rings, the tracks, and hitting a moving target the size of a dinner plate at 500 yardds required patience, not speed.

But nobody wanted patience. They wanted noise. And now on a muddy trail in the Philippines, that lack of patience was about to get them killed. The Japanese tanks were done waiting. The lead tank signaled the others. The distinct metallic slam of a breach locking shut drifted across the gap. They were loading armor-piercing rounds.

They were going to volley fire. eight guns against one. Sergeant Miller grabbed Jenkins by the shoulder of his flight suit and shook him. He screamed that they were going to die. He screamed that Jenkins had to pull the trigger. The loader, a big guy named Ricksite, was curled up on the floor of the turret, clutching a high explosive shell to his chest, praying in Italian.

The smell of fear was overpowering. It was a sour animal stink that filled the cramped space. Jenkins felt the hand on his shoulder. He heard the screaming, but he pushed it all away. He went into the place he always went when he looked through the glass eye of the scope. The world inside the periscope was silent. It was a circle of magnified light crossed by thin black lines.

In that circle, the Japanese tanks looked huge. Jenkins saw the rust on their fenders. He saw the unit markings painted in white on their turrets. He saw the commander of the lead tank dropping back into his cupula to give the order to fire. Jenkins knew exactly what was about to happen. If he fired a standard shot at the center of the lead tank, he might disable it.

But the momentum would carry the wreck forward and the tanks behind it would just push it out of the way or drive around it. He would kill one and the other seven would kill him. He needed a roadblock. He needed to turn that lead tank into a wall of dead steel that the others couldn’t pass. He didn’t aim for the turret. He didn’t aim for the hull.

He moved the gun down. He tapped the hydraulic traverse handle, nudging the massive barrel a fraction of an inch to the right. He was aiming for the drive sprocket, the tooth wheel at the very front of the track that pulled the tank forward. It was a target no bigger than a hubcap.

If he missed by 6 in, the shell would bury itself in the mud or skip harmlessly off the angled armor. “Tick-tock!” Miller screamed, his voice cracking with hysteria. “Shoot the gun!” Jenkins took a breath. He held it. He felt the vibration of the tank’s idling engine in his chest. He felt the sweat dripping off his nose.

He watched the crosshair settle over the drive sprocket of the lead tank. It wasn’t just a shot, it was a gamble. He was betting the lives of four men on his ability to thread a needle with a 15-lb explosive shell. The Japanese gunner in the lead tank was already pulling his trigger. Jenkins could see the barrel jerking as the enemy prepared to fire.

Time seemed to stop. The nickname didn’t matter anymore. The mockery didn’t matter. The instructors who said he was too slow were thousands of miles away. Here, in the sweating, suffocating iron belly of the sledgehammer. There was only the geometry. There was only the line between his gun and the enemy’s track.

Jenkins tightened his grip on the solenoid switch. He didn’t jerk it. He squeezed it. The 75mm gun recoiled with a violence that shook the entire tank. Inside the turret, the air instantly filled with the acrid biting smell of burnt propellant. The breach block slammed open, ejecting the spent brass casing onto the metal floor with a heavy hollow ring.

For a split second, the crew of the sledgehammer was blind, their vision obscured by the smoke and the dust shaken loose from the ceiling. But Jenkins didn’t need to see the explosion to know he had hit his mark. He felt it. He felt the heavy thud of the shell striking home, a vibration that traveled through the ground and up through the suspension of his own tank.

He didn’t cheer. He didn’t shout. He simply watched the periscope as the smoke cleared. His face pressed against the rubber eyepiece. 70 yard ahead, the lead Japanese tank was no longer a threat. It was a roadblock. Jenkins shell had struck the drive sprocket exactly where he had aimed. The impact had shattered the heavy steel wheel and snapped the track links like a cheap necklace.

The track unspooled onto the mud, a useless ribbon of metal. The momentum of the moving tank did the rest. With one track gone and the other still powering forward, the type 97 slew violently to the right. It skidded sideways, digging a trench in the soft earth until it slammed broadside into the thick trunk of a mahogany tree. It was stuck perfectly perpendicular to the trail. It blocked the path completely.

The trap was set. Inside the Sherman, the panic paused for a heartbeat. Sergeant Miller stopped screaming. He stared through his vision block at the burning wreck of the lead tank. He couldn’t believe it. He had expected a center mass shot, a shot that might have bounced or just punched a clean hole.

Instead, Jenkins had surgically removed the enemy’s ability to move. But Jenkins wasn’t looking at his handiwork. He was already moving. While the rest of the crew was staring at the fire, Jenkins was tapping the traverse handle. The electric motor winded as the turret rotated. This was the moment where the tick- tock nickname usually became an insult.

In a standard engagement, the gunner is supposed to hit the next closest target. The second Japanese tank was right there, stuck behind the wreck of the first one. It was a sitting duck. Miller opened his mouth to order Jenkins to fire at it, but Jenkins didn’t stop on the second tank. He kept the turret spinning. He passed the third tank.

He passed the fourth. He was swinging the gun all the way to the left, aiming toward a small gap in the bamboo thicket where the trail curved back into view. Miller grabbed Jenkins shoulder again, confused and terrified. He thought Jenkins had lost his mind. He thought the pressure had finally broken him.

Why was he ignoring the enemy right in front of them? But Jenkins shook the hand off. He knew something Miller didn’t. He knew that if he killed the second tank now, the tanks at the back of the column would realize the trap. They would throw their machines into reverse. They would back up around the bend and escape.

Or worse, they would flank the Sherman through the jungle. Jenkins didn’t just want to kill the leader. He wanted to kill them all. And to do that, he had to seal the exit. Through the gap in the trees, Jenkins saw the rear of the Japanese column. The eighth tank was just visible, its exhaust puffing blue smoke as the driver idled, waiting for the traffic jam ahead to clear.

The Japanese commander in the rear had no idea what was happening. He couldn’t see the lead tank. He just knew the column had stopped. He was safe, or so he thought. He didn’t see the muzzle of the Sherman’s gun poking through the ferns 70 yard away. Jenkins settled the crosshairs. He didn’t rush. He took a breath, letting the air out slowly to steady his hands.

He waited for the tank to rock forward slightly on its suspension. 1 second, 2 seconds, 3 seconds. The loader Ricksai had slammed a fresh armor-piercing shell into the brereech. He tapped Jenkins on the leg to signal the gun was up. Jenkins didn’t fire immediately. He made a micro adjustment to the elevation. He was aiming for the engine deck, the thin armor on the back of the tank where the fuel and the motor lived.

He squeezed the solenoid. The gun roared again. The shell screamed through the gap in the trees. It cleared the bamboo by inches. It struck the eighth tank in the rear quarter. The effect was catastrophic. The shell didn’t just penetrate. It gutted the machine. The engine block shattered. The fuel tanks ignited instantly.

A column of vertical flame erupted from the engine grates, shooting 40 ft into the air. The rear tank died where it stood, turning into a burning cork in the bottle. Now the six tanks in the middle were trapped. They couldn’t go forward because of the first wreck. They couldn’t go backward because of the fire.

They were locked in a kill box. The jungle exploded into chaos. The Japanese crews in the middle six tanks realized they were trapped. Panic took over. Engines revved as drivers tried to turn their tanks around, but the trail was too narrow. They crashed into each other. They scraped against the rock walls of the pass.

They were like rats in a barrel. And then they started shooting. They couldn’t see the Sherman clearly through the smoke, so they fired at the muzzle flash. 47 mm shells began to hammer the front of Jenkins tank. The sound was deafening. It wasn’t like the movies. It was like being inside a giant church bell that was being hit by a sledgehammer.

The impacts didn’t penetrate the thick front armor of the Sherman, but they rang the hole with a violence that made the crews teeth ache. Shrapnel from the shattering shells sprayed across the vision blocks, cracking the glass. Dust and rust flaked off the interior walls, filling the air with a gritty haze.

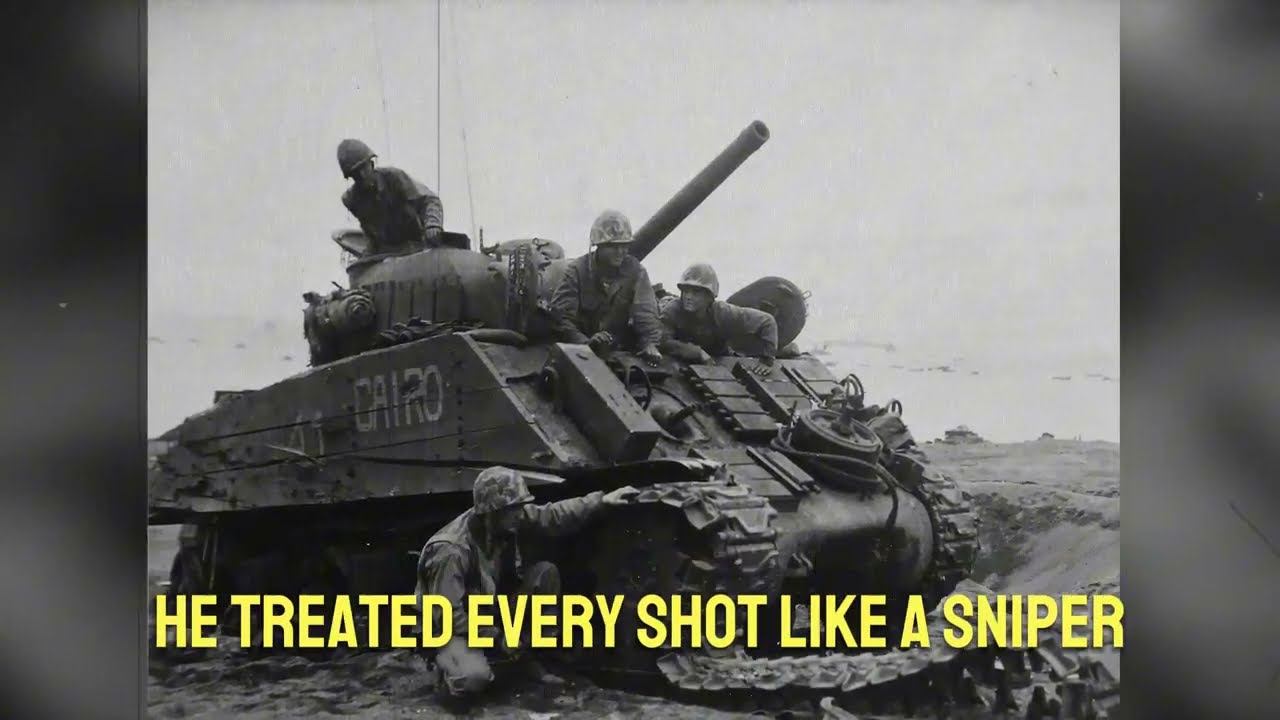

Miller was shouting again, but Jenkins tuned him out. He was in his rhythm now. This was the tick- tock rhythm that everyone had mocked. In the chaos of a firefight, most gunners just point and shoot. They pump rounds down range as fast as they can, hoping to hit something. Jenkins didn’t do that. He treated every shot like a sniper.

He knew he had a limited amount of ammunition. He knew that if he heated up the barrel too much, his accuracy would drift, so he slowed down. He traversed the turret back to the second tank in the line. The Japanese driver was frantically trying to push the wreck of the lead tank out of the way. The tracks were spinning in the mud, throwing up rooster tales of filth.

Jenkins watched the tank struggle. He waited. He waited until the Japanese tank lurched upward, its belly exposing the thin armor underneath. It was a shot that lasted for a fraction of a second. Jenkins took it. The shell hit the underside of the Japanese tank. It punched straight through the floor and exploded inside the crew compartment.

The hatch blew open. Smoke poured out. That was three down. The loader Rickai was working like a machine. He was grabbing shells from the ready rack, slamming them into the gun and clearing the brass. His hands were slippery with sweat and oil. His knuckles were bleeding from scraping against the breach block. He didn’t say a word.

He just fed the gun. Every time the brereech slammed shut, he tapped Jenin’s leg. That tap was the only communication they needed. It was a heartbeat. Load, tap, aim, fire. The heat inside the Sherman was climbing. It was past 120° now. The gun breach radiated heat like an open oven door. The ventilation fan hummed, but it couldn’t keep up with the propellant fumes.

Jenkins eyes were stinging from the smoke. Sweat ran into them, blurring his vision. He blinked it away. He kept his face pressed to the sight. The fourth tank in the Japanese line decided to fight. The commander realized he couldn’t move, so he rotated his turret toward the Sherman. He fired. The shell struck the Sherman’s gun mantlet, the thick shield around the barrel.

Sparks showered the front of the tank. The impact rocked the Sherman back on its suspension. Inside, Jenkins head slammed against the periscope pad. He tasted blood. His lip was split, but he didn’t pull back. He just wiped his mouth with the back of his glove and reacquired the target. He saw the Japanese muzzle flash. He saw the enemy gunner loading for a second shot.

Jenkins didn’t aim for the hull this time. He aimed for the turret ring, the seam where the moving turret met the body of the tank. It was a weak point. If he hit it, he would jam the turret, freezing the enemy gun in place. He took his 3 seconds. 1 2 3. He fired. The shell struck the ring with a shower of sparks.

The force of the impact lifted the Japanese turret off its bearings. It jammed instantly, stuck at a useless angle. The Japanese crew blayed out, scrambling into the jungle. That was four down. But the enemy wasn’t done. They were desperate. The fifth tank in the line did something insane. The driver realized he couldn’t shoot his way out, so he decided to ram his way out.

He revved his engine and charged the wreck of the fourth tank. He climbed up over the engine deck of his own dead comrade, crushing the metal, trying to use the wreck as a ramp to get a shot at the Sherman. It was a suicidal maneuver. The Japanese tank tilted dangerously, its tracks grinding on the steel of the dead tank below it.

For a moment, it looked like it might work. The Japanese tank crested the pile of wreckage, its gun leveling directly at Jenkins. It was a clear shot. Jenkins stared down the barrel of the 47 mm cannon. He could see the rifling inside the muzzle. He knew that at this range, even a small shell could find a weak spot in his armor.

He had to fire first, but he couldn’t just fire anywhere. If he hit the sloped front armor, his shell might ricochet over the top. He needed a flat surface. He waited. The Japanese tank lurched forward, dipping its nose as it came over the crest. That dip exposed the flat vertical plate of the driver’s compartment.

It was exposed for less than a second. A snapshooter would have missed it. A panicked gunner would have fired high. Jenkins was neither. He was tick- tock. He watched the nose dip. He watched the flat steel fill his sight and he squeezed. The shell hit the driver’s plate dead center. The impact stopped the Japanese tank in midair.

It slumped back onto the wreck lifeless. Five down, three to go. The noise inside the tank was tapering off. The Japanese returned fire had stopped. The remaining three tanks were hidden behind the wall of burning metal Jenkins had created. They were trapped in the smoke, blinded by the fires of their own platoon.

But that didn’t mean they were dead. Jenkins knew that a wounded animal is the most dangerous kind. He knew they were back there waiting, listening. The loader Rick’s ice slumped against the turret wall, gasping for air. I’m out of ready rounds, he croked. I got a pull from the floor racks.

Miller looked at Jenkins. The commander’s face was pale, streaked with soot. He wasn’t screaming anymore. He looked at the gunner with a strange expression, something between fear and awe. He had just watched the man, he called, slow dismantle an armored column with the precision of a surgeon removing a tumor. Get the rounds, Ricksite, Miller whispered. His voice was Jenkins.

Keep watching that smoke. If anything moves, you put a hole in it. Jenkins didn’t answer. He didn’t nod. He just kept his eye on the scope. His finger rested lightly on the trigger. He wasn’t thinking about the five tanks he had killed. He was thinking about the three he hadn’t. He watched the wall of black smoke swirling ahead.

And then through the haze, he saw a shadow move. The pass had gone quiet, but it was a heavy, suffocating kind of silence. Five burning wrecks lay scattered across the trail, sending up a wall of black oil smoke that blocked out the sun. Behind that wall, three Japanese tanks were still alive.

They were invisible, hidden in the gray haze. But Jenkins knew they were moving. He could feel the vibration of their engines through the soles of his boots. The floor of the Sherman was vibrating like a plucked guitar string. Inside the turret, the heat had become a physical weight. The ventilation fan was churning the air, but it was just pushing the hot acrid smell of cordite around the crew compartment.

Every surface in the tank was hot to the touch. The breach block of the 75 mm gun sizzled when drops of sweat fell onto it. Jenkins sat with his eyes pressed to the rubber cups of the periscope. His vision was tunneling. The sweat ran down his forehead and stung his eyes, but he didn’t blink. He knew that the Japanese commanders were talking to each other right now.

They were planning. They knew they couldn’t go backward, and they knew they couldn’t charge straight into the gun that had just killed five of their friends. They had to try something different. They had to get an angle. The first move came from the left. The sixth tank in the column didn’t try to drive down the trail.

Instead, the driver turned his machine toward the steep ravine wall. He revved the diesel engine until it screamed, and the tank began to climb the slope. It was a desperate maneuver. The tracks clawed at the mud and roots, tearing up the vegetation. The tank tilted at a crazy angle, its nose pointing at the sky, exposing its belly.

The Japanese commander was trying to get high ground. He wanted to climb above the smoke and fire down into the thin roof armor of the Sherman. Jenkins saw the trees shaking on the left slope. He didn’t swing the turret fast. He moved it with that maddening, deliberate slowness that drove his instructors crazy.

He turned the traverse handle, bringing the gun around. He spun the elevation wheel, cranking the barrel up until it hit the mechanical stop. He watched the dark shape of the Japanese tank emerging from the ferns 20 ft up the bank. It was sliding in the mud, fighting gravity. The Japanese gunner was struggling to depress his gun, fighting the tilt of his own vehicle.

A fast gunner would have fired at the first glimpse of metal. Jenkins waited. He waited for the Japanese tank to slip. The heavy machine lost traction on a patch of wet clay. It slid backward a few feet and for a split second, it stopped moving as the driver slammed on the brakes. That was the moment. The tank was stationary, hung up on a root ball, its suspension compressed.

Jenkins aimed for the drive wheel at the rear of the track. If he broke that, gravity would do the rest. He squeezed the trigger. The Sherman rocked back. The shell slammed into the rear sprocket of the climbing tank. The metal shattered. The track snapped and unraveled like a dead snake. Without the track to hold it, the tank lost its grip on the slope.

It rolled backward, flipping over onto its side, then onto its roof. It tumbled down the ravine wall, crashing through the brush until it landed upside down on the trail with a sound like a dropped dumpster. The engine stalled. The track stopped spinning. That was six down, but the distraction had worked.

While Jenkins was dealing with the climber, the seventh tank had made its move. It had used the noise of the engagement to creep forward through the smoke. It pushed the burning wreck of the fifth tank aside, using the dead hull as a shield. The Japanese gunner was smart. He didn’t come out into the open.

He stayed behind the cover, just poking his gun barrel and a sliver of his turret out around the side. He was hunting. He was waiting for Jenkins to reload. Ricksai, the loader, was struggling. The ready rack on the turret floor was empty. He had to pull ammunition from the wet storage racks in the floor of the hull.

He ripped up the floor plates, reaching down into the glycol-filled bins to drag out a heavy, slippery shell. His hands were shaking. He fumbled the shell, almost dropping it. “Hurry up!” Miller hissed from the commander’s seat. He could see the Japanese muzzle poking out from behind the wreck. It was swiveing toward them. Jenkins didn’t look at his loader.

He kept his eyes on the enemy gun barrel. He could see the black hole of the muzzle staring at him. He knew he had about 2 seconds before the enemy fired. He couldn’t fire back because his gun was empty. He had to move. He shouted for the driver to rock the tank. Kowalsski slammed the Sherman into first gear and punched the gas.

The tank lurched forward 3 ft. Then he slammed it into reverse and jerked it back. The Japanese gunner fired. The shell missed the turret by inches, passing through the space where the Sherman had been a second earlier. The air pressure from the passing round slapped against the side of the tank like a physical hand.

The shell exploded against the rock wall behind them, showering the engine deck with shrapnel. Ricksai slammed the fresh round into the brereech. The block slid home and locked up. He screamed. Jenkins stopped the driver. He had the shot now. The Japanese tank had fired and missed. Now it was his turn, but the enemy was still mostly hidden behind the wreck.

Jenkins couldn’t see the hull. He could only see the gun barrel and the very edge of the turret cheek. It was a target the size of a shoe box. Jenkins took a breath. He ignored the sweat stinging his eyes. He ignored the heat. He focused on the geometry. He aimed for the very edge of the enemy turret, right where the armor curved back.

If he hit it straight on, the round might glance off the curve. He had to catch the flat spot. He made a micro adjustment, tapping the handle with his fingertip. He fired. The 75 mm armor-piercing shell struck the edge of the Japanese turret. It didn’t penetrate. Instead, it caught the heavy steel casting and ripped the entire turret off the tank.

The force of the impact sheared the bolts that held the turret ring together. The Japanese turret flipped into the air like a coin and landed in the mud with a wet thud. The headless body of the tank sat there smoking. Seven down. Now there was only one left. The eighth tank, the leader of the rear guard, the one that had been trapped at the very back of the line.

This commander had watched seven of his squad die. He knew he couldn’t climb the walls. He knew he couldn’t win a sniping duel against the monster in the Sherman. He had one option left. He decided to charge. Through the thick black smoke, Jenkins saw the shape coming. It wasn’t creeping. It was moving fast. The engine was roaring at red line.

The Japanese Type 97 burst through the wall of smoke like a bull entering an arena. It smashed through the debris of the scattered Rex, bouncing violently over the torn up ground. The commander had his hatch open. He was screaming orders, driving his tank straight at the Sherman. He wasn’t trying to flank. He was trying to close the distance so he couldn’t miss.

He was going to ram them if he had to. Jenkins spun the traverse handle, but the handle didn’t move. The electric motor groaned and died. The fuse had blown from the heat and the constant use. The power traverse was gone. Jenkins shouted that he had lost power. He grabbed the manual traverse crank. It was a heavy steel wheel that moved the turret with gears and muscle.

He started cranking it with both hands, his biceps burning. The turret moved agonizingly slow. The gears clicked rhythmically. The Japanese tank was closing fast, 60 yard, 50 yd. The enemy gunner was firing on the move. Shells slammed into the front armor of the Sherman. They gouged deep furrows in the steel, but they didn’t penetrate.

The Japanese tank was rocking so hard the gunner couldn’t aim for the weak spots. He was just hammering the front plate. Jenkins cranked the wheel. He watched the enemy tank filling his sight. It was getting bigger every second. He could see the rivets on the hull. He could see the mud caked on the tracks.

He needed to get the gun around. The Japanese tank was drifting to the right, trying to get around the Sherman’s side to hit the thinner armor. Jenkins cranked harder, his breath coming in ragged gasps. >> >> The turret groaned as it rotated 30 yards. The Japanese tank stopped firing. The gunner was holding his shot.

He was waiting until he was alongside the Sherman to put a round through the flank. It was a race. Jenkins turned the wheel. The Sherman’s gun barrel chased the speeding tank. It was moving in slow motion. The Japanese tank was faster. It was going to win the race to the corner. Driver, pivot right, Jenkins screamed. He needed help.

He couldn’t traverse fast enough, so he needed the whole tank to turn. Kowalsski locked the right track and gunned the engine. The Sherman skidded in the mud, pivoting its entire hull to the right. The movement threw the crew around the turret, but it swung the gun barrel those last critical degrees.

The muzzle of the Sherman’s gun lined up with the oncoming tank. The Japanese tank was 20 yard away. It filled the entire periscope. Jenkins didn’t aim for a specific part. At this range, there was no need for geometry. There was no need for finesse. It was a pointblank execution. The Japanese tank fired at the same instant.

The shell struck the Sherman’s gun mantlet and shattered, sending a spray of molten metal across the vision blocks. Jenkins squeezed the trigger. The Sherman fired. The blast was so close that the muzzle flash enveloped the Japanese tank. The 75 mm shell hit the enemy machine dead center in the front slope. At 20 yards, the velocity was devastating.

The shell punched through the front armor, traveled through the fighting compartment, punched through the engine block, and exited out the rear. The Japanese tank stopped instantly as if it had hit a concrete wall. The sudden stop lifted the rear tracks off the ground. It slammed back down. Smoke poured from every hatch.

There was no fire this time, just a sudden catastrophic death. The machine sat there, steaming in the rain, 10 yards from the front of the Sherman. Jenkins took his hands off the traverse wheel. They were trembling uncontrollably. He looked through the periscope. Nothing moved. The trail was a graveyard.

Eight Japanese tanks lay wrecked in a line stretching back into the jungle. The smoke from the fires drifted straight up into the canopy, mingling with the mist. Inside the turret, nobody spoke. The silence was louder than the gunfire. It rang in their ears. Rickside dropped the next shell he was holding. It rolled across the floor with a metallic clatter.

Miller sat in his commander’s seat, staring out the vision block at the smoking ruin in front of them. He blinked, trying to clear the soot from his eyes. He looked down at the back of his gunner’s head. Jenkins slumped forward, resting his forehead against the gun’s sight. He was exhausted. His flight suit was soaked through with sweat. His arms felt like laid.

He took a long, shaky breath, tasting the copper tang of blood from his split lip. He checked the ammunition counter. They had started with 90 rounds. They had four left. He had fired 86 shells in 20 minutes. He had killed eight tanks, and he had done it all without rushing a single shot.

He reached up and wiped the fog from the periscope glass. He scanned the tree line one last time, looking for movement, looking for the next threat. But the jungle was still. The ambush was broken. The sledgehammer was the only thing left alive in the pass. The silence that followed the battle was heavier than the steel hull of the tank.

For 20 minutes, the Villa Trail had been the loudest place on earth, filled with the screaming of engines and the thunder of high velocity cannons. Now the only sound was the crackle of burning diesel fuel and the rhythmic ticking of cooling metal. Inside the turret of the sledgehammer, the air was still thick with the gray fog of propellant smoke.

The floor was buried under a carpet of hot brass casings that shifted and clinkedked whenever the loader moved his feet. Sergeant Miller was the first to move. He popped the commander’s hatch and pushed it open. The fresh jungle air rushed in, smelling of rain and wet earth, mixing with the stink of the fight.

Miller pulled himself up and looked out. The scene in front of him looked like a scrapyard in hell. Eight Japanese tanks lay broken in the mud. They were arranged in a chaotic line. Some burning, some smoking, some sitting perfectly still as if they were parked. But when Miller looked closer, he saw the pattern.

He saw the first tank turned sideways, its track shattered, blocking the road. He saw the last tank in the column, got shot through the engine, sealing the exit. He saw the turret of the seventh tank lying upside down in the mud. It wasn’t random violence. It was a dissection. Miller dropped back down into the turret. He looked at Jenkins.

The corporal was sitting slumped on his stool, wiping grease off his hands with a rag. He didn’t look like a hero. He looked like a man who had just finished a long shift at a factory. Miller didn’t say anything. He couldn’t. The nickname Tik Tok died in his throat. He realized that while he had been screaming for speed, Jenkins had been buying them survival with every second he wasted.

The crew climbed out of the tank. They stood in the mud, their legs shaking from the adrenaline dump. They walked down the line of Rex. Ricksai, the loader, stopped at the third tank. He traced the hole in the armor with his finger. It was right through the driver’s vision port. A target the size of a postcard hit from a moving tank while under fire.

Ricksai looked back at the Sherman, then at Jenkins. He shook his head. It was impossible shooting. It was the kind of shooting you saw on a range with a stationary target and a cool barrel, not in a jungle ambush. With the heat rising to 120°, they spent an hour waiting for the rest of the American column to catch up.

When the relief force arrived, the lead jeep stopped short of the carnage. A major jumped out. He looked at the single battered Sherman sitting in the middle of the trail, its front armor gouged and scarred by non-penetrating hits. Then he looked at the eight dead Japanese tanks. He asked Miller where the rest of his platoon was.

Miller just pointed at Jenkins. It was just him, sir, Miller said. Just him and the clock. The drive back to the base was slow. The sledgehammer was hurting. The suspension groaned with every bump. The engine was overheating. The radiator clogged with mud and debris. But they made it. When they rolled into the motorpool, word had already spread.

Men from other crews came out to look at the tank. They touched the deep gouges in the steel plate where the Japanese shells had bounced off. They counted the kill rings that Rickai had already started chalking onto the barrel. Eight rings, one engagement. But the most important change wasn’t the chalk marks. It was the silence.

Nobody made a joke about Jenkins being slow. Nobody asked if he had fallen asleep on the trigger. When Jenkins climbed out of the hatch, the other gunners just watched him. They saw a man who moved with a deliberate heavy grace. They realized that what they had mistaken for slowness was actually a total lack of panic.

In a world where everyone was rushing to die, Jenkins was the only one taking the time to stay alive. Clarence Jenkins finished the war in the Philippines. He fought in a dozen more engagements from the mountains of Luzon to the streets of Manila. He never changed his style. He never snapped the gun.

He never fired wild. He remained the tick- tock gunner until the very end. By the time the Japanese surrendered in August of 1945, Jenkins had one of the highest confirmed kill counts of any tank gunner in the Pacific theater. But he never bragged about it. He never wrote a book. He never told war stories in the bar.

When the army discharged him, Jenkins went back to Oklahoma. He returned to the farm he had left three years earlier. He put away his uniform and his gunner’s quadrant. He went back to fixing tractors and harvesting wheat. To his neighbors, he was just a quiet man who was good with machinery. If you brought him a broken thresher or a stalled truck, he wouldn’t fix it fast.

He would stand there looking at the engine, rubbing his chin. He would take his time. He would study the problem until he understood it completely. And then he would fix it once and it would never break again. Years passed. The war faded into history. The Sherman tanks were melted down for scrap or put on concrete plints in public parks.

The memory of the Villa Verd Trail was swallowed by the jungle, but the men who served with Jenkins never forgot. Miller, the commander who had screamed at him to shoot, told the story to his grandchildren. He told them about the heat and the smoke. He told them about the panic, and he told them about the farm boy who refused to be hurried.

Miller would say that the world is full of people who run, people who react without thinking, who speak without listening, who shoot without aiming. He said that speed is cheap. Anyone can go fast, but it takes a special kind of courage to go slow when everything around you is burning. It takes a special kind of discipline to trust your own eyes when everyone else is screaming for you to close them and pull the trigger.

Clarence Jenkins died in 1992. He was 78 years old. He died sitting on his front porch, watching a storm roll in across the plains. He was watching the clouds, calculating the wind, waiting for the rain. He was patient to the end. His tombstone in the local churchyard doesn’t mention the eight tanks. It doesn’t mention the silver star he was awarded.

It just has his name, his dates, and a single line of scripture. Be still and know. Most people walking past that grave have no idea who lies beneath it. They don’t know that the quiet farmer was once the deadliest surgeon in the Pacific. They don’t know that his patient saved the lives of four men in a steel box on a mountain road. They just see a name.

But we rescue these stories to ensure that Clarence, Tik Tok, Jenkins doesn’t disappear into silence. We tell them because they remind us of a simple truth that is often lost in our modern high-speed world. Precision beats power. Timing beats speed. And sometimes the only way to win the race is to stop running.

So the next time you feel the pressure to rush, the next time the world is screaming at you to move faster, remember the sledgehammer. Remember the gunner who took 3 seconds to save his life. Take a breath, find your mark, and squeeze. Don’t jerk.