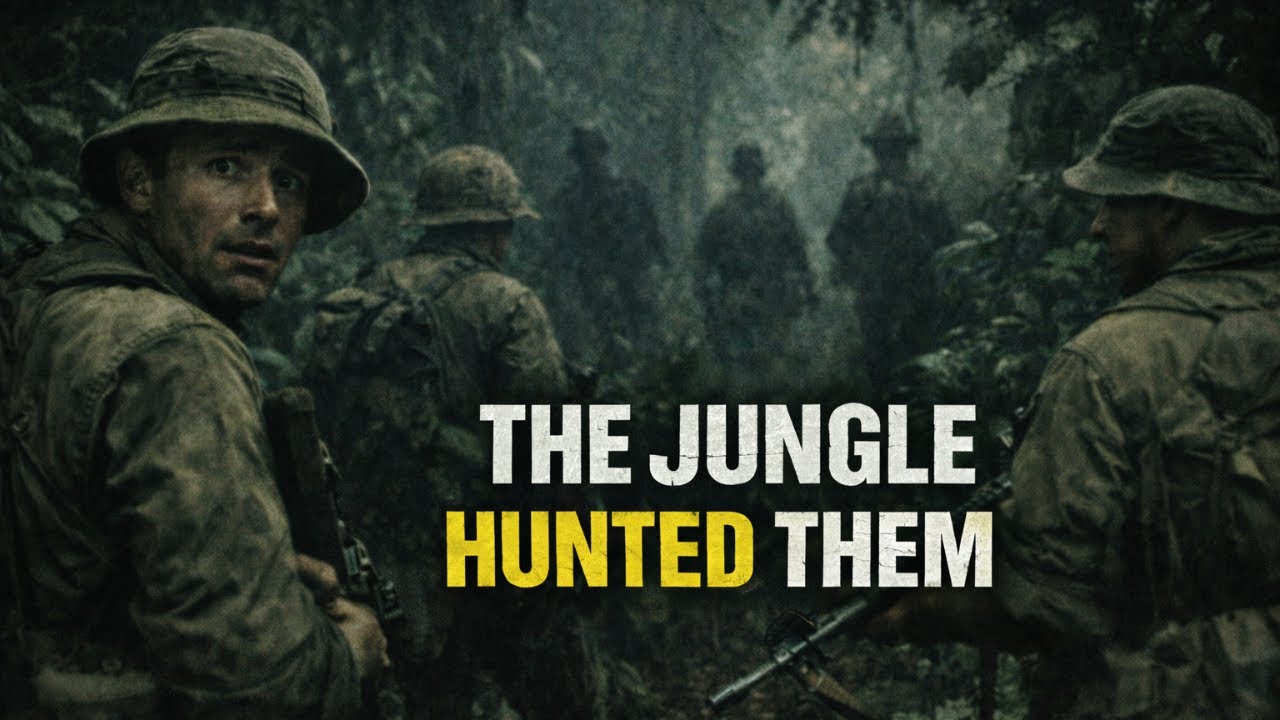

The most terrifying soldiers in the Vietnam War were not American. They did not arrive with roaring helicopters or waves of artillery. They did not announce themselves with radio chatter or tracer fire. They moved without sound, without light, and without warning. Deep in the jungles of Southeast Asia, a small group of Australian soldiers became so effective, so invisible, and so psychologically devastating that the Pentagon classified everything about them for half a century.

Their success didn’t just challenge the enemy, it challenged the entire American understanding of how the war was supposed to be fought. If you want more true stories that were buried, denied, or quietly erased from official history, subscribe now because some of the most important truths only survive when people keep listening.

For decades, US military archives contain sealed reports that hinted at something deeply unsettling. Not atrocities, not betrayals, but allied units whose methods were so effective that acknowledging them would have forced American commanders to confront an uncomfortable reality. Their own doctrine was failing.

These files referenced patrols with kill ratios so extreme that analysts assumed clerical errors. 500 to1. Numbers that made no sense in conventional warfare. Numbers quietly removed from briefings, ignored in strategy sessions, and omitted from official histories. The whispers always pointed in the same direction.

The Australian Special Air Service Regiment. In 1968, at the height of the Vietnam War, an American Green Beret Staff Sergeant Michael Brennan volunteered for a joint patrol with the Australians. He expected to observe Allied reconnaissance techniques. What he encountered instead would fracture his understanding of warfare, of humanity, and of himself.

Not because of brutality, not because of bloodshed, but because he watched men who had stopped fighting a war and had started hunting human beings. The Vietkong had a name for them, Ma Rang. Jungle ghosts. Brennan spent 11 nights moving through the jungle with Australian SAS operators. 11 nights without radios.

11 nights without resupply. 11 nights watching men disappear so completely that even trained American special forces could not follow them. When he returned, he requested immediate extraction. His debriefing was sealed. His psychiatric files were reclassified and his testimony was buried under layers of Allied secrecy.

Why? Because the Australians weren’t winning battles. They were erasing the enemy’s confidence that the jungle could protect them. They didn’t destroy camps, they violated them. They didn’t chase fighters. They turned survivors into messengers who spread terror faster than any propaganda campaign ever could.

Weapons were abandoned. Bases were deserted. Entire regions went quiet. And that silence was the problem. Because acknowledging what the Australians had learned would mean admitting that warfare at its most effective entered a gray zone no democratic government wanted to explain. A place where soldiers stopped behaving like soldiers and started behaving like predators.

A place where rules still existed but only on paper. This is not a story about heroes or villains. It is a story about what happens when men are trained to remove the final restraints of civilized warfare. About why the Pentagon buried their success. About why one American soldier never slept in a bed again.

This is the story of the night hunters. The patrol did not begin in combat. It began at the staging area in early 1968. An American Green Beret Staff Sergeant Michael Brennan reported to an Australian Special Air Service Regiment detachment expecting a standard reconnaissance mission. Under US doctrine, long range patrols were designed to last 3 days, supported by scheduled communications, emergency extraction windows, and aerial resupply if required.

The Australian patrol Brennan joined was planned for 11 days. The difference was immediately apparent. Australian operators carried significantly lighter loads. There were no radios allocated for the first 8 days of the operation. Ammunition was limited. Rations consisted primarily of rice, dried fish, and locally sourced supplies.

Every piece of equipment was stripped of excess material. Items that could reflect light, make noise, or snag vegetation had been removed. To American observers, the approach appeared unsafe. Captain David Morrison, the patrol commander, explained the rationale succinctly. American reconnaissance units planned around the possibility of contact.

Australian SAS patrols planned around the assumption that contact represented failure. The objective was not to fight, but to observe, track, and disappear without detection. The patrol stepped off in the late afternoon. Within the first hour, Brennan lost visual contact with the majority of the unit.

There was no fixed formation consistent with US training doctrine. The Australians did not move in identifiable columns or staggered files. Their spacing varied constantly, sometimes compressing, sometimes expanding with no verbal coordination. Communication occurred through pre-arranged gestures, posture changes, and timing cues developed through long operational familiarity.

Observers later noted that this movement pattern eliminated predictable signatures. There was no single point of failure, no leader position to target, no rhythm an enemy tracker could exploit. At one point, Morrison approached Brennan from behind without producing audible disturbance, covering more than 10 m through dense undergrowth undetected.

The demonstration was intentional. Brennan was instructed to place his feet exactly where Morrison had stepped, highlighting how even trained Western soldiers generated noise and visual disturbance through habitual movement patterns. That evening, the patrol halted. No conventional sentry positions were established.

No rotations were announced. Operators selected natural concealment and remained stationary for extended periods, maintaining situational awareness without visible motion. One SAS operator remained motionless for several hours, responding to distant environmental sounds with minimal controlled movement. The behavior was later described by observers as indistinguishable from the surrounding terrain.

This was not a technique taught in American special forces training at the time. The Australian method emphasized synchronization with the environment rather than domination of it. Movement was timed with wind, insect activity, and ambient noise. Vegetation was allowed to close naturally behind the patrol.

The terrain was not treated as an obstacle, but as a partner. By the end of the first night, Brennan recognized that the Australians were not applying stealth as a tactical layer. Stealth was the operating state. Their presence in the jungle left no discernable trace that conventional tracking methods could reliably follow. Subsequent debriefings would describe this phase of the patrol as the moment American observers understood that Australian SAS operations did not rely on superior equipment or technology.

Their effectiveness came from doctrinal assumptions that rejected visibility, communication, and even movement as default behaviors. In the jungle, the Australians were not attempting to remain unseen. They were functioning as though they had never been there at all. By the third night, the patrol had not fired a single round.

This was not accidental. It was deliberate. Australian SAS operations in Vietnam were designed around a principle largely absent from American doctrine at the time. Intelligence was more valuable than contact, and fear was more decisive than firepower. The jungle was not treated as terrain to be crossed or dominated.

It was treated as an active system, one that could be read, exploited, and weaponized. The patrol’s first significant discovery came in the form of a concealed Vietkong supply cash. To American forces, such a find typically triggered immediate destruction. air strikes or artillery would be called in to deny the enemy material.

The Australian response was marketkedly different. The cache was left untouched. Australian operators documented its contents, mapped access routes, and identified subtle indicators of recent use. foot placement patterns, vegetation disturbance inconsistent with animal movement, soil compression suggesting carried loads. These signs indicated not only who used the cash, but how often, in what numbers, and under what physical condition.

Rather than destroy the site, the patrol withdrew and waited. This decision reflected a broader Australian doctrine. Infrastructure was not the target. Networks were. When a Vietkong courier eventually arrived, he was not engaged. He was followed for hours. The Australians maintained visual and auditory tracking without alerting the target.

They observed contact points, identified secondary caches, and mapped a web of movement that no interrogation could have revealed. By the time the courier reached his destination, the patrol had identified multiple supply nodes, weapons storage sites, and a regional command location that had eluded American search and destroy operations for over a year.

No contact had been made, no shots fired. This capability was enabled in part by the integration of indigenous tracking techniques unfamiliar to most Western militaries. Australian SAS training at the time included instruction derived from Aboriginal tracking traditions developed over tens of thousands of years.

These methods emphasized environmental literacy rather than mechanical tracking. Operators learned to read ground sign invisible to untrained observers. The angle of crushed foliage. The behavior of insects displaced by recent movement. variations in sunlight reflection indicating disturbed leaf orientation. These indicators allowed trackers to reconstruct movement patterns across terrain that appeared untouched.

The knowledge was not symbolic or ceremonial. It was operational. Australian soldiers trained in these techniques could determine how many individuals had passed through an area, how recently, whether they were burdened with equipment, and whether they were moving cautiously or with confidence. This allowed patrols to anticipate enemy behavior rather than react to it.

The jungle, once considered an equalizer favoring insurgents, became a surveillance medium. American observers noted that Australian patrols rarely pursued targets directly. Instead, they allowed enemy movement to continue uninterrupted while collecting information over extended periods. This patience contrasted sharply with American emphasis on rapid engagement and measurable results.

The Australians understood that destroying an enemy position removed only a location. Understanding how and why it existed exposed the entire structure behind it. By the fifth day, the patrol had assembled an intelligence picture far exceeding what conventional operations typically produced in weeks. Yet none of it appeared in body count statistics.

There were no craters, no visible signs of engagement, and no immediate evidence of success. This invisibility extended beyond the jungle. Because these methods produced results that could not be easily quantified, they were rarely highlighted in coalition reporting. Their effectiveness existed outside standard metrics.

As a result, they remained poorly understood even by allied forces operating alongside them. The patrol was not hunting individuals. It was mapping a living system. And once that system was fully understood, the Australians prepared to do something American forces rarely attempted. They prepared to break it without destroying it. The objective was not destruction.

By the seventh night, Australian SAS operators had completed their reconnaissance of a Vietkong regional headquarters concealed deep within the jungle. The location had been active for months, coordinating logistics, personnel movement, and local security operations. American forces had previously attempted to locate it through aerial reconnaissance and search and destroy missions without success.

The Australians did not request air support. Instead, the patrol observed the compound for several hours. Sentry patterns were recorded. Gaps in coverage were identified, not measured in meters, but in seconds. The Australians noted moments when overlapping fields of observation briefly failed. These windows were small, irregular, and would not have been detected through conventional surveillance.

Just before midnight, the patrol moved. There was no preparatory fire, no diversion, no signal. Five operators entered a defended enemy position without alerting a single sentry. Later assessments concluded that the patrol exploited timing, environmental masking, and predictable human behavior rather than physical force.

They did not engage enemy personnel directly. What followed was not an attack in the conventional sense. The Australians later referred to it only as a preparation. Official records did not describe the details. However, post operation observations and fragmentaryary testimony indicated that the patrol deliberately altered the environment in ways intended to be discovered but not immediately understood. Objects were repositioned.

Personal effects were moved. Items associated with spiritual or cultural significance were arranged in patterns familiar to local belief systems. No western military training formally addressed these practices. Yet the Australians demonstrated detailed knowledge of their psychological impact. The patrol withdrew before dawn.

At first light the effects became visible. The compound remained intact. No structures were damaged. No bodies were discovered. Yet leadership personnel had vanished. Survivors abandoned weapons, equipment, and supplies. Observers later reported panic-driven flight rather than organized withdrawal. American surveillance noted a sudden collapse in local Vietkong activity across the surrounding region.

Radio traffic dropped sharply. Movement along established trails ceased. Several units relocated without orders. Interviews conducted years later with former Vietkong personnel described the incident not as a military defeat but as a violation. The jungle itself was perceived as hostile. The enemy was described as unseen, unknowable, and immune to retaliation.

The Australians had achieved an outcome that conventional force could not. They had removed the enemy’s confidence in concealment. For American observers, the implications were troubling. The operation produced no measurable metrics suitable for reporting. There were no confirmed kills, no destroyed facilities, and no captured material.

Yet, the operational effect exceeded that of large-scale kinetic actions conducted elsewhere in the province. The Australians had not eliminated the enemy. They had made the environment uninhabitable. This method represented a form of psychological warfare operating outside formal doctrine.

It did not violate the laws of armed conflict as written. Yet, it challenged the assumptions upon which those laws were based. There was no clear engagement, no visible enemy action to respond to, and no identifiable perpetrator. The jungle itself appeared to be the weapon. Following the operation, the patrol did not pursue fleeing personnel.

They did not exploit the collapse with direct action. Instead, they observed secondary effects, confirming that fear propagated faster than force. By the time the patrol extracted, the region had gone quiet. For the Australian SAS, the mission was considered successful. For American observers, it raised questions that would not be formally addressed for decades.

Because if warfare could be conducted without battles, without destruction, and without identifiable perpetrators, then the existing framework of modern military doctrine was incomplete. And the Australians had just demonstrated how dangerous that gap could be. Staff Sergeant Michael Brennan requested extraction on the 12th day. Official records do not explain the request.

They note only that it was denied until the patrols scheduled completion. When Brennan returned to base, his debriefing was conducted under conditions rarely applied to Allied observers. Portions of the transcript were immediately classified. Others were later reclassified at the request of the Australian government. Brennan did not report combat trauma in the conventional sense. He had not been wounded.

He had not engaged in firefights. He had not lost members of his patrol. Yet within months, his behavior began to change in ways that confounded military psychologists. He reported persistent unease rather than fear. Difficulty sleeping not due to nightmares but to silence. An inability to move through wooded environments without unconsciously scanning for signs of presence.

His psychiatric evaluations described a condition inconsistent with standard combat stress reactions. The issue was not what he had survived. It was what he had understood. Brennan had witnessed a form of warfare that operated beyond the assumptions of Western military doctrine. A method that relied not on firepower or numerical superiority, but on patience, perception, and psychological dominance.

The Australians had demonstrated that trained soldiers could function as predators, removing themselves so completely from detection that resistance became irrelevant. This knowledge proved corrosive. Brennan completed additional deployments, but avoided joint operations with Australian units. His marriage deteriorated. He slept seated, facing entrances.

He insisted on darkness rather than illumination. These behaviors persisted long after his discharge. In 1979, Australian officials formally contacted US authorities regarding the sensitivity of Brennan’s medical records. They requested continued classification of material related to SAS operational methods still in use.

The request was granted. By then, the influence of Australian doctrine had already spread quietly. Extended patrol operations, emphasis on intelligence over engagement, psychological effects prioritized above body counts. These principles entered American special operations training without attribution. The methods were adopted.

The source was not acknowledged. Brennan lived the remainder of his life carrying knowledge that could not be openly discussed and could not be unlearned. He died in 2017. His journals released postuously confirmed what classified files had implied for decades. Australian SAS effectiveness in Vietnam was not exaggerated.

It was intentionally understated. Their success presented a problem no government wished to confront. That the most effective form of warfare might require soldiers to abandon the final constraints of civilized conduct, not through atrocity, but through invisibility. The Australians returned home and largely remained silent.

The American observer never truly did. His final writings did not condemn what he had seen, nor did they praise it. They simply recorded the cost of understanding it. He wrote that he had learned something fundamental in the jungle. That war was not about force. It was about will. And that when men learn to move without being seen, to strike without being understood, and to leave without evidence, they crossed a line most societies prefer to pretend does not exist.

The jungle, he noted, had not changed him. It had revealed what was already possible. And that knowledge followed him long after the war ended. The jungle swallowed light like a living thing.