July 27th, 1944. The German defensive line in Normandy collapsed. After 7 weeks of bloody stalemate in the hedge, American forces had finally broken through. Tanks were pouring into open country. German units were retreating in confusion. The road to Paris was open. The man who made it happen stood in his command post watching the reports come in.

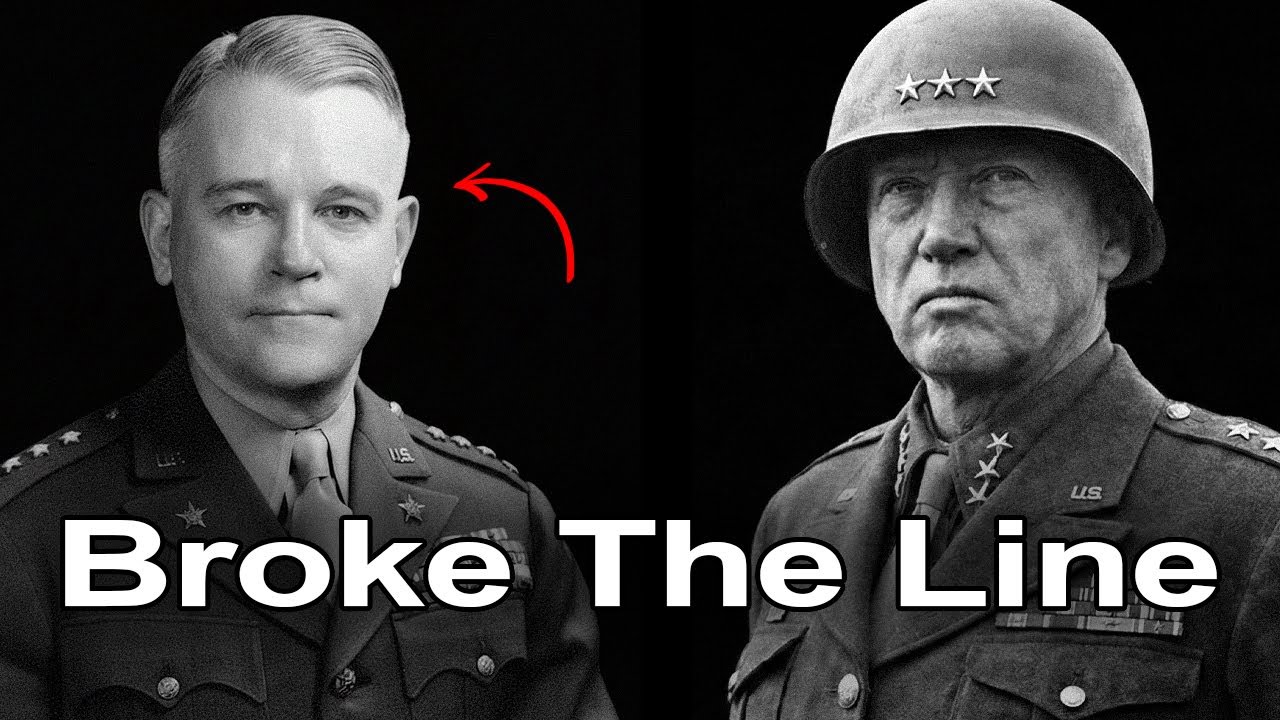

Major General Jay Lton Collins had just accomplished what no Allied commander had managed since D-Day. He had cracked the German line wide open. Four days later, George Patton’s Third Army would charge through that gap and race across France. Patton would become the most famous American general of the war. His face would be on magazine covers.

His name would become synonymous with victory. Collins would be forgotten. The breakthrough that made Patton famous belonged to another general entirely. Jay Lton Collins was 48 years old in 1944. That made him the youngest core commander in the entire United States Army. Douglas MacArthur had rejected him for core command in the Pacific.

Too young, MacArthur said, not enough seniority. Omar Bradley didn’t care about seniority. He cared about results and Bradley had Eisenhower’s ear. Collins had earned his nickname in the Pacific. He’d commanded the 25th Infantry Division on Guadal Canal in New Georgia. His aggressive tactics and rapid advances earned him the name Lightning Joe.

When Omar Bradley needed a core commander for the most critical mission of the Normandy invasion, he asked for Collins specifically. Bradley had known Collins before the war at the infantry school. He remembered a young officer who was smart, aggressive, and unafraid to take risks. The assignment Bradley had in mind would require all three qualities.

Collins seventh core drew the Utah beach assignment for D-Day. But the beach landing was just the beginning. His real mission was Sherborg. The Allies needed a deep water port to sustain their armies in France. Every bullet, every gallon of fuel, every replacement soldier would have to come through that port.

Without Sherborg, the invasion would eventually starve. The original plan called for capturing Sherborg within 9 days of landing. Military planners considered this optimistic. The Germans had turned the port into a fortress. They’d had four years to build defenses. Artillery positions covered every approach. The garrison was determined to hold.

Collins had to land his core on a hostile beach, fight across the Coten Peninsula, and capture one of the most heavily defended ports in Europe. He had less than 3 weeks to do it. June 6th, 1944. Seventh Corps landed at Utah Beach with lighter casualties than anyone expected. Collins immediately pushed inland while other cores consolidated their beach heads.

Seventh Corps drove north toward Sherborg. The fighting was brutal. German defenders contested every hedge, every village, every crossroad. Collins lost men every day, but he never stopped advancing. On June 22nd, Collins forces reached the outskirts of Sherborg. The German garrison commander refused surrender demands.

Collins ordered a coordinated assault from three directions. 5 days later, on June 27th, organized resistance ended. Sherborg belonged to seventh core. Collins had captured the most strategically important objective in Normandy. The port that would sustain millions of Allied soldiers was in American hands. The news made headlines for exactly one day.

But the spotlight didn’t last. Because south of Sherborg, the real nightmare was just beginning. The Boaz was killing the American army. Ancient hedros divided Normandy into thousands of tiny fields. Each hedro was an earththen wall 4 feet high, topped with dense vegetation. Tanks couldn’t push through.

Infantry couldn’t see beyond the next field. Every hedge was a potential ambush. German machine guns waited in concealed positions. Mortars zeroed in on gaps in the vegetation. American soldiers died trying to cross open ground they couldn’t avoid. Progress was measured in yards per day. Casualties mounted into the thousands. It was a claustrophobic nightmare.

Men fought and died for a single field, only to realize there were thousands more just like it waiting for them. The morale of the American army was beginning to crack under the strain of an enemy they could rarely see until it was too late. By mid July, First Army had advanced barely 15 miles from the beaches.

The original plan called for being 60 mi inland by this point. Bradley was desperate. His army was bleeding out in the hedge with no end in sight. He needed someone to break the stalemate. Someone aggressive enough to punch through the German line. He needed Lightning Joe Collins. Bradley’s plan was called Operation Cobra.

It was the most ambitious American offensive of the war so far. The concept was simple. Concentrate overwhelming force on a narrow front, blast a hole through the German line with carpet bombing, then send armor pouring through before the Germans could recover. The execution would be anything but simple. Bradley chose a fivemile stretch of road west of St.

Low as the breakthrough point. He assigned the assault to seventh corps. Collins would lead the attack. Some officers questioned the choice. Collins had just finished the Sherbore campaign. His core was exhausted. Why not give the mission to fresher troops? Bradley’s answer was blunt. Collins was his best core commander. The breakthrough required aggressive leadership and quick decisions.

Collins delivered both. The fate of the Normandy campaign now rested on Collins’s shoulders. July 24th, 1944. 2,000 American aircraft prepared to deliver the largest tactical bombing mission of the war. Then everything went wrong. Weather forced the postponement, but not before some bombers had already released their payloads.

Bombs fell short. American positions were hit. Over 150 American soldiers were killed or wounded by their own air force. Collins watched the disaster unfold from his command post. The attack was postponed to the next day. July 25th. The bombers returned. This time the weather held. Over 4,000 tons of bombs fell on a rectangle barely 2 mi wide.

The earth shook for miles in every direction, but the bombs fell short again. 111 American soldiers were killed and nearly 500 wounded. Among the dead was Lieutenant General Leslie McNair, the highest ranking American officer killed in the European theater. For the men on the ground, the world simply ended. The noise was so deafening it ceased to be sound and became physical pressure.

When the dust settled, the screams weren’t in German. They were American. Collins had lost hundreds of men before his infantry even started moving. And nobody knew if the bombing had worked. The only way to find out was to attack. The first reports were discouraging. Collins infantry pushed forward into the bombed area, expecting shattered German defenses. Instead, they found survivors.

Machine gun positions that had somehow escaped the bombardment opened fire. Forward movement was agonizingly slow. By nightfall on July 25th, 7th Corps had barely penetrated the German line. Bradley was worried. If the Germans held, Cobra would fail like every other offensive in the hedge. Colin saw something different in the reports.

German counterattacks were disorganized. Prisoners seemed dazed and confused. Communication between German units had broken down. The German line wasn’t holding. It was cracking. Collins made a decision that would change the war. Instead of waiting for his infantry to secure the breakthrough, he ordered his armor forward immediately.

It was a massive risk. If the German line solidified, American tanks would be trapped in a meat grinder. In that moment, Collins was entirely alone. If he was wrong, he wouldn’t just lose his job. He would destroy the second and third armored divisions. The entire invasion force was holding its breath, waiting for him to give the order.

But Collins trusted his instincts. The Germans were reeling. Now was the moment to strike. July 26th, Collins armor found the gaps and exploited them. Tank columns bypassed German strong points that would have stopped infantry. They drove deeper into enemy territory than any American unit had managed since D-Day. German commanders tried to establish new defensive lines.

American tanks arrived before the lines could form. By July 27th, the German 7th Army was reporting catastrophic losses. Seven separate ruptures in their defensive line. No reserves to plug them. The careful grinding hedge war was over. This was mobile warfare now. Collins’s seventh core had broken the German army in Normandy.

The breakthrough every Allied commander had dreamed of since June 6th was finally happening. Open country lay ahead. Paris was possible. The German army in the west was on the verge of collapse. All of this belonged to Lightning Joe Collins for exactly five more days. August 1st, 1944. George Patton’s Third Army became operational.

Patton had been waiting for this moment since the slapping incidents nearly ended his career. He’d spent months commanding a phantom army as part of a deception operation. Now he finally had real troops. His orders were to exploit the breakthrough Collins had created. Patton did exactly that. Third Army poured through the gap.

Seventh Corps had opened and raced across France. Patton’s tanks covered distances that seemed impossible. Town after town fell. The German army retreated in chaos. The media fell in love with Patton’s dash across France. War correspondents competed to describe his latest advances. Newspapers ran headlines about Patton’s genius, Patton’s audacity, Patton’s unstoppable army.

Nobody mentioned who had created the gap Patton was exploiting. Nobody asked who had broken the German line in the first place. Collins kept fighting while the cameras followed Patton. The pattern repeated throughout August and September. Collins 7th core did the hard fighting. They captured Aen, the first German city to fall to the Allies.

They pushed through the Ziggf freed line fortifications. Patton got the headlines. It wasn’t deliberate theft. Patton was simply more quotable, more photogenic, more dramatic. He gave reporters colorful quotes. He wore distinctive uniforms. He made great copy. Collins was quiet and professional.

He let his results speak for themselves. Patton carried ivory-handled revolvers and carefully cultivated the image of the ultimate warrior. Collins looked like a bank manager who happened to be wearing a uniform. In the theater of war, the audience always watches the actor, not the stage hand. Even if the stage hand is the one pulling the ropes, not even Bradley, who knew the truth, could shift the public’s focus.

By the time the Battle of the Bulge began in December 1944, most Americans had never heard of Lightning Joe Collins. December 16th, 1944, the Germans launched their last major offensive in the West. While fifth core held the vital northern shoulder at Elsenborn Ridge, Collins was brought in to lead the counterattack.

Seventh Corps drove into the German flank from the north, helping crush the penetration. Patton’s dramatic relief of Baston dominated the headlines. His turn north maneuver became legendary. Collins’s counterattack from the north was equally important, but received a fraction of the coverage. The pattern held to the very end of the war.

When Germany surrendered in May 1945, Collins had fought from Utah Beach to the Ela River. He had captured Sherborg. He had broken the German line at Cobra. He had helped stop the bulge. Bradley later wrote that if the army had created another field army in Europe, Collins would have commanded it despite his youth and lack of seniority.

German generals considered Collins one of the two best American core commanders they faced. None of it mattered to public memory. After the war, Collins became Army Chief of Staff during the Korean War. He served from 1949 to 1953. He received the Army Distinguished Service Medal three times. The Soviets awarded him the Order of Subarov twice.

His nephew, Michael Collins, would pilot the Apollo 11 command module while Armstrong and Uldren walked on the moon. None of it made Lightning Joe Collins a household name. When Americans think about the Normandy breakout, they think about Patton racing across France. They don’t think about the general who made that race possible.

Sherborg’s capture is a footnote. Operation Cobra is remembered for what came after Patton’s race across France, not for who made it possible. The youngest core commander in the army won every major engagement he fought. He delivered the most important port and the most important breakthrough of the campaign.

History forgot him anyway. The men who served under Collins knew what he had accomplished. Bradley knew. Eisenhower knew. the public never learned. Collins died in 1987 at age 91. His obituaries mentioned his service, but couldn’t make him famous after 40 years of obscurity. Patton’s legend only grew after his death. Movies were made.

Books filled shelves. His face became the image of American military power. Collins got a paragraph in other people’s biographies. The breakthrough that changed the war belonged to Lightning Joe Collins. The credit belonged to someone else. That’s how history works sometimes. The man who does the heavy lifting isn’t always the one who gets the statue.

Collins understood this. He never complained publicly. He just kept doing his job. But none of that changes what happened on July 27th, 1944. The German line broke. Lightning Joe Collins made it happen. Patton made it famous. Both statements are true. But history has a habit of remembering the thunder of Patton’s tanks and forgetting the lightning that struck the blow.