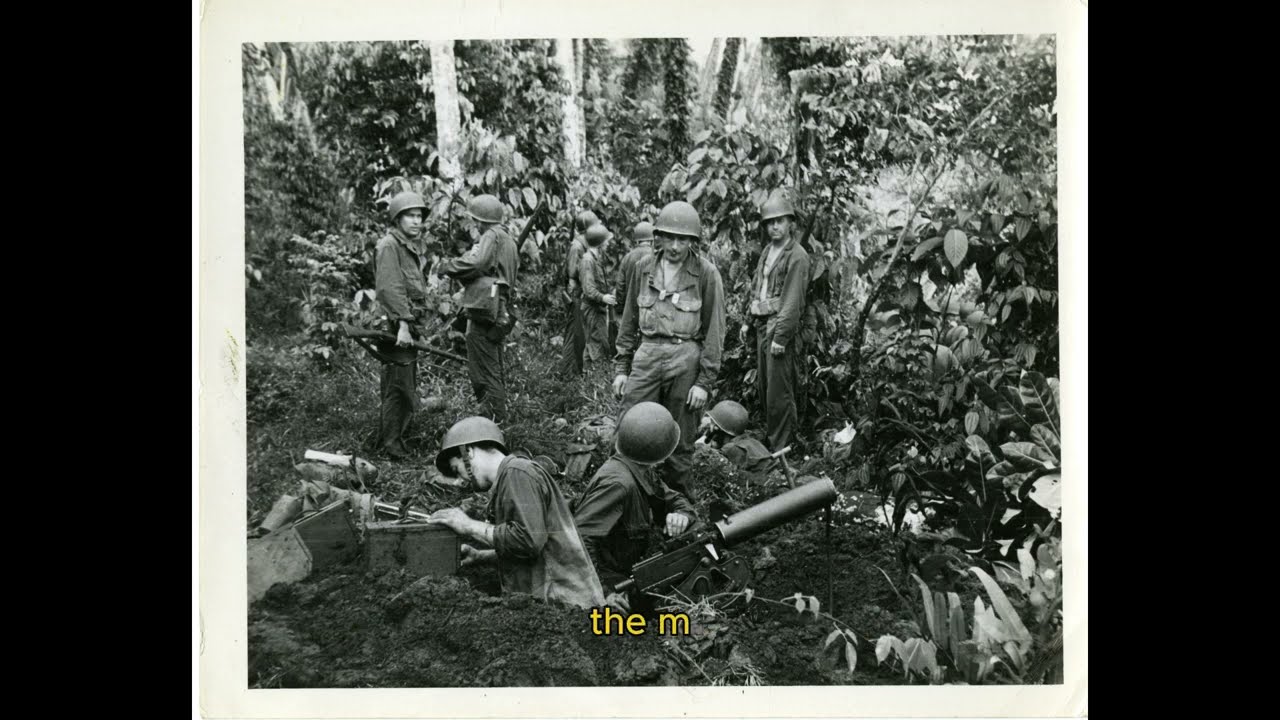

October 24th, 1942. Henderson Field, Guadal Canal. The jungle breathes with deadly silence before erupting in the most terrifying sound a Marine could hear. 800 Japanese soldiers screaming their death charge through the darkness. Gunnery Sergeant John Basselone crouches behind what his men called museum pieces.

Water cooled machine guns from the Great War. 100 lb of obsolete iron that newer, lighter models had replaced. The M1919 could fire a thousand rounds per minute. Fast, portable, modern. Everything the core wanted for jungle warfare. But as the bonsai charge crashes into American lines, something impossible happens. The new guns fall silent, barrels glowing cherry red, mechanisms seizing in the humid heat.

While the ancient M1917A1s with their bulky water jackets and slow 600 round rate keep firing belt after belt, hour after hour, without stopping, without overheating, without mercy. 800 enemy dead would fall that night to guns the Marines thought were holding them back. But these outdated machine guns held a secret the modern military had forgotten.

The humid air of Guadal Canal clung to everything like a wet shroud as Captain Roy Smith stood at the edge of Henderson Field, watching his Marines wrestle with their assigned equipment. The M1917A1 machine guns sat in their positions like relics from another war, which Smith reflected grimly, they were. Each gun weighed over 100 lb, fully loaded, its massive water jacket gleaming dullly in the tropical sun.

The cooling system alone held nearly a gallon of water, adding pounds to an already cumbersome weapon that seemed designed for the static trenches of France, not the mobile warfare of the Pacific. Smith’s frustration had been building for weeks. The newer M1919 machine guns were everything the core claimed to want in jungle fighting.

Lighter, more portable, capable of firing up to 1,000 rounds per minute compared to the M1917 Steady 600. The air cooled system eliminated the need for water, reducing weight and complexity. On paper, it was the perfect weapon for rapid advances through dense terrain where every ounce mattered.

Yet here they were, stuck with guns that belonged in a museum. The Marines shared his skepticism. Private First Class Martinez struggled to maneuver his M197 into position, cursing under his breath as the tripod legs caught in the undergrowth. Sergeant, this thing weighs more than my girlfriend back home,” he muttered, earning scattered chuckles from his squadmates.

The comparison wasn’t far off. The M1917A1 tipped the scales at 103 lb with its tripod, water jacket, and ammunition, while the M1919 came in at a spelt 41 lb. But weight was only part of the problem. The water cooling system required constant maintenance in the field. The jackets needed refilling. The connections had to be checked for leaks, and the whole apparatus demanded careful handling to prevent damage.

In contrast, the M1909’s air cooling meant Marines could pick up and move without worrying about slloshing water or complex plumbing. It fired the same 306 cartridge, but did so with modern efficiency. Smith walked the line, observing his men’s struggle with the antiquated weapons. The core had issued them these guns for Henderson Fields defense, but every tactical manual emphasized mobility and firepower.

The Japanese were masters of rapid infiltration, using the jungle’s cover to close distance before American forces could react. Logic dictated that lighter, faster firing weapons would give his Marines the edge they needed. The technical specifications told a clear story. The M19019 could sustain rates of fire approaching 1,000 rounds per minute in short bursts, nearly double the M1917’s steady 600 rounds per minute.

For a defensive position expecting human wave attacks, that extra firepower seemed crucial. The air cooled barrel could handle extended firing as long as crews allowed brief cooling periods between sustained bursts. Yet, something nagged at Smith as he watched his gunners train. The M197’s water jacket wasn’t just dead weight. It was a massive heat sink that absorbed and dissipated thermal energy with ruthless efficiency.

The newer guns relied on air circulation around their barrels, which worked well in moderate climates, but struggled in the suffocating humidity of the South Pacific. At 90% humidity and temperatures pushing 90°, air cooling became less effective with each degree of barrel heat. The ammunition requirements also differed significantly.

Both guns fired the same cartridges, but their feeding systems worked differently. The M1907 used continuous belts that could be linked together for sustained fire, while the M1919 relied on shorter belts that required more frequent reloading. In a prolonged engagement, those extra seconds spent changing belts could prove fatal.

Smith’s doubts crystallized during a training exercise 3 days before the Japanese attack. His gunners had been practicing sustained fire drills, burning through belt after belt of ammunition to simulate the kind of defensive barrage they might need against a bonsai charge. The M1919s performed admirably for the first few minutes, their higher rate of fire chewing through targets with impressive speed.

But as the exercise continued, problems emerged. The air cooled barrels began to glow. First a dull red, then brighter. As the metal absorbed more heat than the humid air could dissipate, gunners were forced to cease fire repeatedly, waiting precious minutes for barrels to cool enough to continue. Meanwhile, the M1917s maintained their steady 600 rounds per minute without interruption, their water jackets absorbing heat and converting it to steam that vented safely away from the mechanism.

By the exercise’s end, the newer guns had fired. fewer total rounds despite their higher cyclic rate, forced into silence by their own heat generation. The older weapons had maintained consistent fire throughout the entire drill, their barrels remaining cool enough to handle even as thousands of rounds passed through their chambers.

Still, Smith found himself conflicted. Training exercises were one thing, but real combat would bring variables no drill could simulate. The Japanese were known for their ferocious night attacks, human waves that relied on shock and speed to overwhelm defensive positions. Would the M197 steady fire be enough against hundreds of screaming enemies? Or would they need the M1919’s rapid burst to cut down attackers before they closed the distance? His Marines continued their preparations with typical military efficiency, but Smith could see the

doubt in their eyes. They trusted their training and their weapons, but these guns felt like anchors holding them to the past. Every other unit in the Pacific seemed to be moving toward lighter, more modern equipment. Only here, defending this crucial airirstrip in the middle of nowhere were they stuck with relics from the trenches of bellow wood. The irony wasn’t lost on Smith.

The same guns that had helped win the Great War were now seen as obsolete, unsuited for modern warfare. Yet, as he watched his gunners master the M1917’s quirks and capabilities, he began to wonder if the core knew something that escaped immediate understanding. Perhaps there was wisdom in choosing tools based on mission requirements rather than technological fashion.

In 72 hours, when the jungle erupted in screams and gunfire, that wisdom would be tested in the most unforgiving classroom of all. The night air carried death across the Ilu River on October 24th. Colonel Kona Ichiki’s voice cut through the darkness as he addressed his assault troops one final time.

800 men of the 28th Infantry Regiment who believed American Marines would crumble before the Emperor’s Steel. His plan was elegant in its simplicity. A frontal assault across the sandbar at the rivermouth, overwhelming the thin defensive line through sheer audacity and superior fighting spirit. The Americans, he assured his officers, had never faced the fury of a true banzai charge.

Captain Smith crouched behind the sandbagged position where gunnery Sergeant Basilone had cited his M1917A1, the water jacket still warm from the afternoon’s final function checks. The machine gun commanded a perfect field of fire across the narrow beach where the river met the sea, its tripod legs driven deep into the coral sand.

Basselone had spent hours adjusting the traverse and elevation, marking reference points with white painted stakes that gleamed faintly in the starlight. The gun’s ammunition belts snaked through the position like metal intestines. 250 rounds linked together and ready to feed into the weapon’s hungry chamber.

The attack began at 0310 with a sound that raised every hair on Smith’s neck. 800 voices screaming in unison as Japanese soldiers poured across the sandbar. They came in waves, bayonets fixed, rifles held high, faces twisted with fanatic determination. The first rank splashed through the shallow water while others pressed behind them.

A human tsunami that seemed unstoppable in the moonlight. Smith’s M1919 gunners opened fire first, their weapons chattering at nearly 1,000 rounds per minute as they poured lead into the charging mass. The effect was devastating, bodies crumpled and fell, blood darkening the sand as the high velocity rounds tore through flesh and bone.

For precious seconds, it seemed the modern guns would justify every tactical manual ever written about rapid defensive fire. But the jungle’s heat had been building in those air cooled barrels all day, and now the sustained firing pushed metal temperatures beyond their limits. The first M1919 fell silent after 90 seconds, its barrel glowing cherry red in the darkness as the gunner frantically signaled for a barrel change.

Another followed 30 seconds later, then a third, their mechanism seizing as thermal expansion locked moving parts in place. Meanwhile, Basselone’s M1917A1 had settled into its rhythm, 600 rounds per minute, steady as a metronome, the water jacket absorbing heat and converting it to steam that hissed softly into the night air.

Smith watched in fascination as the old gun maintained its rate of fire without pause, each round precisely placed into the killing zone Baloni had marked during daylight reconnaissance. The Japanese kept coming despite the carnage, their training overriding survival instincts as they stepped over fallen comrades and pressed forward.

Smith could see individual faces now, eyes wide with battle fury, mouths open in screams that mixed with the machine guns steady hammering. Some carried explosive charges strapped to their bodies, willing to die if they could reach the American positions. The M19019 struggled back into action as crews completed hurried barrel changes, but their interrupted fire had allowed the assault to gain momentum.

Japanese soldiers reached the outer wire obstacles, cutting through defensive barriers with wire cutters and bare hands. The gaps in covering fire had cost them dearly. What should have been an impenetrable wall of lead had become sporadic bursts separated by critical silences. But the MI197A1 never stopped.

Basselone fed belt after belt into the weapon’s action. His movement smooth in practice despite the chaos erupting around him. The water cooled system had turned the gun into an engine of destruction that functioned regardless of how many rounds passed through its barrel. Steam rose from the water jacket like incense from some mechanical alter, but the gun’s mechanism remained cool and precise.

Smith found himself mesmerized by the weapon’s relentless efficiency. Each burst lasted exactly the same duration. Each pause for belt changes took precisely the same time. Each correction of fire followed the same deliberate process. The gun had become an extension of Balone’s will, responsive to his slightest adjustment, yet independent of human limitations like fatigue or heat buildup.

The Japanese charge began to falter as bodies piled up in the killing zone. The survivors found themselves trapped between the river behind them and the unceasing fire from the M1917A1 ahead. Some attempted to outflank the position by moving along the beach, but Baselone simply traversed the gun left and right, his pre-marked reference points allowing him to maintain accurate fire even in complete darkness.

By dawn, the sandbar was carpeted with bodies. Nearly 800 Japanese soldiers who had believed their spirit could overcome American firepower. The M1907A1 sat silent at last, its water jacket still warm, but its mechanism ready for another engagement if needed. Around it, the newer M1919s showed the scars of their thermal ordeal.

Barrels discolored by heat, some warped beyond repair. Smith walked among his gunners as they cleaned their weapons and counted ammunition expenditure. The statistics told a story that no training manual had prepared him for. The M1917A1 had fired over 4,000 rounds during the engagement without a single mechanical failure.

Its water cooled system maintaining consistent performance throughout the entire battle. The M19119s had fired fewer rounds in total despite their higher cyclic rate, forced into silence repeatedly by overheating that left crucial gaps in the defensive fire. The tactical implications were staggering. In jungle warfare, where humidity and heat were constant enemies, the older weapons cooling system provided a decisive advantage that modern technology had inadvertently discarded.

The M1919’s air cooling worked perfectly in temperate climates, but struggled in the South Pacific’s oppressive environment. Weight and complexity, the very factors that made the M1917A1 seem obsolete, had proven to be strengths when the mission demanded sustained firepower. Basselone emerged from his position like a man awakening from a trance, his uniform soaked with sweat and condensation from the gun steam vents.

He had spent six hours feeding belts into the weapon’s action, making minute adjustments to maintain accuracy as targets shifted and moved. The gun had become part of him, its rhythm matching his heartbeat, its needs anticipated before they arose. As the sun climbed higher, and the full scope of their victory became clear, Smith felt his skepticism dissolving into something approaching reverence.

The museum pieces had proven their worth in the most demanding test possible, outlasting and outperforming their modern replacements when it mattered most. The jungle had revealed a truth that peaceime planning had missed. Sometimes the oldest solution was also the best one. The transformation began in the hours following the Tenneroo massacre as word of the M19.

17A1’s performance spread through the Marine Corps chain of command like wildfire. Captain Smith found himself summoned to division headquarters 3 days after the battle where Major General Alexander Vandergrift waited with a stack of afteraction reports and a question that would reshape Pacific theater tactics. The commanding general’s weathered face showed the strain of defending Henderson Field, but his eyes held a sharp intelligence that had kept the Marines alive through months of desperate fighting. Vandagramrif spread the

engagement reports across his makeshift desk, pointing to ammunition expenditure figures that told an extraordinary story. The M1917A1 positions had maintained continuous fire for over 6 hours, burning through more than 20,000 rounds without a single weapon failure. Meanwhile, positions equipped with M1919s had suffered multiple barrel changes and extended cooling periods that created dangerous gaps in defensive coverage.

The newer guns had fired impressive bursts, but couldn’t sustain the prolonged engagement that jungle warfare demanded. Smith watched as Vandergri traced casualty figures with his finger, noting how enemy dead clustered heaviest in front of the water cooled positions. The M1917A1’s steady 600 rounds per minute had created killing zones that remained consistently lethal throughout the engagement, while the M1919’s higher cyclic rate had proven meaningless when thermal limitations forced repeated ceasefires.

The general’s conclusion was stark. The core had been prioritizing the wrong specifications in their quest for modernization. Within 48 hours, urgent communications flowed back to Marine Corps headquarters in Quanico, requesting immediate redistribution of M17A1 machine guns to frontline units. The weapon that had been relegated to training roles in rear area security suddenly became the most requested item in the Pacific supply chain.

Ordinance officers scrambled to locate stored guns and ship them forward. While armorers worked around the clock to refurbish weapons that had been gathering dust in statesside warehouses. The technical re-evaluation went beyond simple ammunition counts. Marine engineers conducted detailed thermal analysis of both weapon systems under combat conditions, measuring barrel temperatures, and calculating heat dissipation rates in tropical environments.

Their findings confirmed what Baselon and his gunners had discovered through brutal experience. Air cooling became progressively less effective as ambient temperature and humidity increased. At Guadal Canal’s typical 90° and 90% humidity, the M1919’s cooling capacity dropped by nearly 40% compared to temperate conditions.

Conversely, the M197A1’s water jacket maintained consistent cooling performance regardless of atmospheric conditions. The system’s thermal mass absorbed heat energy and converted it to steam, creating a continuous cooling cycle that functioned independently of air temperature or humidity. The weight penalty that had made the weapon seem obsolete was actually stored cooling capacity that paid dividends during sustained engagement.

Smith became an unofficial evangelist for the older weapon, briefing newly arrived units on lessons learned from the Teneroo battle. He emphasized that the M1917A1 required different tactics than the newer guns. Crews needed to think in terms of sustained fire rather than rapid bursts, and positioning became critical since the weapons weight made quick displacement difficult.

But properly employed, it could deliver firepower that lighter weapons simply couldn’t match in jungle conditions. The vindication extended beyond individual battles as subsequent engagements confirmed the pattern. During the October offensive, when General Harukichi Hayakutake committed his 17th Army to a coordinated assault on Henderson Field, M1917A1 positions again proved decisive.

The Japanese threw regiment after regiment against marine lines, expecting American defenses to buckle under sustained pressure. Instead, they encountered machine gun fire that never slackened, never paused for extended cooling periods, never created the gaps that assault troops could exploit. Gunnery Sergeant Mitchell Page exemplified the new tactical approach during the savage fighting on October 26th.

When his position came under overwhelming attack, he used the M190 on 17A1’s sustained fire capability to single-handedly hold a critical section of the perimeter. While lighter weapons would have forced him to pause repeatedly for cooling, the water cooled gun allowed him to maintain continuous fire even when fighting alone.

His Medal of Honor citation would specifically mention the weapon’s reliability under extreme conditions. The logistical implications rippled throughout the Pacific theater as commanders requested M1917 A1s for defensive positions while retaining M1919s for mobile operations. The heavier guns proved ideal for fixed fortifications where their weight wasn’t a disadvantage.

While lighter weapons remained better suited for advancing forces that needed portability over sustained fire capability, this tactical distribution maximized each weapon’s strengths while minimizing their weaknesses. Training protocols evolved to accommodate the M1907A1’s unique requirements. Gunner schools emphasized water management, teaching crews to monitor jacket levels and maintain steam vents under combat conditions.

Range cards became more critical since the weapon’s weight made rapid target acquisition difficult, but its sustained accuracy made careful pre-planning devastatingly effective. Ammunition handling procedures adapted to the longer belt lengths that the water cooled system could accommodate. Smith found himself assigned to develop new doctrine incorporating lessons learned from Guadal Canal’s fighting.

The manual he produced emphasized environmental factors that peaceime testing had missed. How humidity affected air cooling, how sustained fire rates differed from cyclic rates, how thermal limitations created tactical vulnerabilities. The document became required reading for machine gun crews throughout the Pacific, spreading Guadal Canal’s hard one knowledge to units facing similar conditions.

The transformation of perception was perhaps most visible in the Marines themselves. Weapons that had once seemed like punishment details became prized assignments as word spread about their battlefield effectiveness. Veterans of Tenaru and subsequent engagements spoke with reverence about guns that had kept firing when everything else fell silent.

The M1917A1 evolved from museum piece to lifesaver in the span of a few desperate nights. By December 1942, as Australian forces relieved the Marines on Guadal Canal, the lesson had crystallized into doctrine. The oldest machine gun in American service had proven superior to its modern replacement in specific conditions, teaching planners that technological advancement didn’t always mean tactical improvement.

Sometimes the best tool for the job was the one that seemed most outdated, validated not by specifications on paper, but by performance under fire. The M1917A1’s resurrection represented more than just equipment redistribution. It embodied a fundamental shift in how the core approached technology adoption.

New wasn’t automatically better if it couldn’t perform the required mission. Weight wasn’t always a disadvantage if it provided essential capabilities. Complexity wasn’t inherently superior to simplicity if battlefield conditions favored robust reliability over sophisticated features. These lessons would influence American small arms development for decades to come.

The vindication of the M199917A1 reached its ultimate expression on Ewima, where John Basselone would carry the lessons of Guadal Canal into his final battle. By February 1945, the Gunnery sergeant had become the Marine Corps’s most celebrated machine gunner, his Medal of Honor citation specifically crediting the water cooled weapon that had saved Henderson Field.

But fame had pulled him away from the front lines. Assigned to statesside war bond tours where his heroic image could inspire civilian support for the Pacific campaign. Baselone’s return to combat duty came at his own insistence. Despite offers of safer assignments that would have kept him alive for the war’s duration, he understood something that rear echelon planners missed.

The M1907A1’s tactical revolution was incomplete without experienced gunners who could exploit its full potential. The weapons resurrection had provided the hardware, but battlefield expertise remained concentrated in veterans who had learned its capabilities through desperate necessity rather than peaceime training.

The sulfur islands black volcanic sand presented new challenges that tested every lesson learned in the jungles of Guadal Canal. Unlike the coral beaches and dense vegetation of the Solomons, Ioima offered little natural cover and no water sources for the M1917A1’s cooling system. Japanese defenders had spent months preparing elaborate tunnel networks and reinforced positions that could withstand prolonged bombardment, creating a killing field where every yard would be purchased with American blood.

Captain Smith, now promoted and assigned to coordinate machine gun employment across the fifth Marine Division, worked with Basselone to adapt water cooled tactics for the new environment. The absence of natural water sources meant crews would have to carry additional supplies or rely on salt water from the sea, requiring modifications to standard operating procedures.

The volcanic terrain offered excellent fields of fire, but little protection from Japanese artillery and mortar fire that could target stationary positions with devastating accuracy. Baselone’s expertise proved invaluable during the planning phase as he identified positions where the M19107A1 sustained fire capability could dominate key terrain features.

The weapon’s weight, still a liability during rapid advances, became an advantage when establishing defensive positions that needed to withstand counterattacks. Japanese tactics on Euoima relied heavily on nighttime infiltration and sudden assaults from concealed positions. Exactly the type of engagement where continuous firepower proved decisive.

The landing on February 19th demonstrated how completely the core had embraced the water cooled weapons tactical role. M1917A1s came ashore in the initial waves. Their crews trained specifically in rapid imp placement techniques that could establish defensive positions within minutes of landing. The gun’s ability to maintain sustained fire became critical as Japanese defenders emerged from concealed positions to contest every beach landing site.

Baselon’s final engagement on February 21st showcased the M1917A1’s evolution from forgotten relic to essential battlefield tool. Leading a machine gun section toward Motoyama airfield number one, he encountered a complex of Japanese bunkers that commanded the approaches to the vital runway. The position required precisely the type of sustained suppressive fire that had made the water cooled gun famous at Guadal Canal, but with tactical refinements developed through three years of Pacific combat.

The engagement began at dawn as basselone section established positions overlooking the Japanese strong point. The M197A1s opened fire in coordinated bursts, their interlocking fields creating a curtain of lead that prevented enemy movement between defensive positions. Unlike the frantic close quarters fighting at Tenneroo, this engagement required precision fire at extended ranges where the weapon’s inherent accuracy proved as valuable as its sustained fire capability.

Japanese defenders responded with mortar and artillery. Fire that forced constant position changes, testing the gun crews ability to maintain continuous fire while under bombardment. The M19117A1’s weight made rapid displacement difficult, but its cooling system allowed crews to maintain fire rates that lighter weapons couldn’t match.

Basselone moved between positions, coordinating fire and ammunition resupply while directing the tactical employment that had become his specialty. The tactical sophistication demonstrated at Ewima represented the culmination of lessons learned throughout the Pacific campaign. Gun crews had mastered water management techniques that maintained cooling efficiency even with saltwater substitutes.

Ammunition handling had evolved to support belt lengths exceeding 1,000 rounds, allowing sustained fire that could last for hours without interruption. Range estimation and target acquisition had become precise sciences that maximize the weapon’s inherent accuracy. More importantly, the M1917A1 had found its proper tactical niche within the CORE’s combined arms doctrine.

Rather than trying to make the weapon something it wasn’t, a lightweight portable gun for rapid advances, Marines had learned to employ it where its strengths provided maximum advantage. Fixed defensive positions, sustained suppressive fire missions, and long range precision engagement had become the water cooled gun specialties. The weapon’s psychological impact on enemy forces had also become a factor in tactical planning.

Japanese troops had learned to fear the distinctive sound of sustained M197A1 fire, recognizing it as a threat that wouldn’t diminish with time or temperature. The gun’s ability to maintain continuous fire created a psychological barrier that complemented its physical effects, forcing enemy units to remain in concealment rather than attempting movement under fire.

Barcelon’s death during the Eoima assault marked the end of an era, but his tactical legacy lived on in the doctrine he had helped develop. The M197A1 continued serving throughout the Pacific campaign. Its role secure as commanders finally understood the difference between technological sophistication and battlefield effectiveness.

The weapon that had seemed obsolete in 1941 had become indispensable by 1945. The broader implications extended beyond individual weapon systems to influence American military thinking about technology adoption. The M190 17A1’s resurrection had demonstrated that battlefield requirements often differed from peaceime specifications, that environmental factors could override theoretical advantages, and that combat veterans experience provided insights that laboratory testing couldn’t replicate. These lessons would reshape

how the military evaluated new equipment, emphasizing realworld performance over abstract capabilities. By war’s end, the M1917A1 had achieved something remarkable. It had successfully defended its relevance against newer technology by proving superior performance in specific conditions.

The weapon’s weight and complexity, initially seen as disadvantages, had proven to be features that enabled capabilities lighter weapons couldn’t match. Water cooling had triumphed over air cooling in environments where sustained fire mattered more than portability. The tactical revolution sparked by Guadal Canal’s desperate fighting had transformed how the Marine Corps thought about firepower, sustainability, and environmental adaptation.

An obsolete weapon had taught modern lessons about the relationship between technology and tactics, proving that sometimes the best solution was the oldest one, refined by experience and validated by results rather than specifications. The final chapter of the M1917A1’s Pacific War began with silence, the kind of profound quiet that follows the end of sustained combat.

Captain Smith stood in the ruins of what had been Shuri Castle on Okinawa, watching his Marines clean their weapons for what many hoped would be the last time. The water- cooled machine guns sat in their positions like sentinels that had witnessed too much, their cooling jackets still warm from the final engagement that had broken Japanese resistance on the island’s southern approaches.

The statistics of the Okinawa campaign told a story that would have seemed impossible 3 years earlier at Guadal Canal. M1917A1 positions had maintained an average uptime of 96% during sustained engagements compared to 72% for air cooled weapons in similar conditions. The difference translated to thousands of rounds that reached their targets instead of waiting in overheated chambers.

firepower that had proven decisive in breaking Japanese defensive positions that had withtood weeks of bombardment. Smith reflected on the transformation he had witnessed. From his initial skepticism about obsolete equipment to his role as one of the weapons primary advocates within the core, the M1917A1 had evolved from burden to blessing through the crucible of combat.

Its limitations revealed its strengths when properly understood and employed. The same weight that made it difficult to maneuver had provided the thermal mass necessary for sustained cooling. The same complexity that required additional maintenance had enabled reliability that simpler systems couldn’t match.

The weapon’s psychological impact had become as important as its physical effects during the prolonged fighting on Okinawa. Japanese defenders [clears throat] had learned to distinguish the M1917A1’s distinctive firing signature from other American weapons, recognizing its sound as a death sentence for any movement within its beaten zone.

The gun’s ability to maintain fire for hours without pause had forced enemy units deeper underground, limiting their ability to coordinate defensive actions or launch effective counterattacks. More significantly, the M197A1 success had fundamentally changed how American forces approached sustained combat operations.

The weapon had demonstrated that firepower sustainability mattered more than peak performance in prolonged engagements, that thermal management was as critical as ammunition supply, and that environmental factors could override theoretical advantages. These lessons had applications far beyond machine gun employment, influencing everything from artillery doctrine to aircraft engine design.

The technical innovations sparked by the weapons renaissance continued evolving throughout the Pacific campaign. Ordinance specialists had developed improved water circulation systems that increased cooling efficiency by 15%, allowing even higher sustained fire rates without overheating. Ammunition feeding mechanisms had been refined to handle longer belt lengths, reducing reload frequency during critical engagements.

Optical sights had been upgraded to take advantage of the weapon’s inherent accuracy at extended ranges. But the most important changes had been tactical rather than technical. Marine Corps doctrine now recognized the M197A1 as a specialized tool optimized for specific missions rather than a general purpose weapon trying to be everything to everyone.

Fixed defensive positions, sustained suppressive fire, and precision engagement at extended ranges had become its acknowledged specialties. This tactical clarity had eliminated much of the confusion that had initially surrounded the weapons employment. The human cost of this education had been enormous.

Veterans like Baloney had paid with their lives to develop the expertise that made effective employment possible. Countless machine gun crews had learned through trial and error. Their mistakes measured in casualties rather than training scores. The knowledge had been purchased with blood and validated through survival, creating a body of tactical wisdom that no peaceime exercise could have generated.

Smith’s afteraction reports from Okinawa would become the foundation for post-war machine gun doctrine, codifying lessons learned through three years of Pacific combat. His analysis emphasized environmental factors that had been largely ignored in pre-war planning, how humidity affected cooling efficiency, how sustained fire requirements differed from burst fire capabilities, how thermal limitations created tactical vulnerabilities that enemies could exploit.

The document would influence American small arms development for decades to come. The broader implications extended beyond individual weapon systems to fundamental questions about military innovation and technology adoption. The M19017A1 success had demonstrated that newer wasn’t automatically better, that battlefield requirements often differed from laboratory specifications, and that combat veterans experience provided insights that theoretical analysis couldn’t replicate.

These lessons would reshape how the military evaluated new equipment, emphasizing proven performance over promised capabilities. As the Pacific War drew to its close, the M1917A1 found itself in an unusual position, an obsolete weapon that had proven superior to its modern replacement in specific conditions.

The tactical niche it had carved out during the jungle fighting of Guadal Canal had expanded throughout the island hopping campaign, providing capabilities that lighter weapons simply couldn’t match when missions demanded sustained firepower over extended periods. The weapons influence on postwar planning was already becoming apparent as military planners prepared for potential conflicts in other tropical environments.

Korea’s mountainous terrain and harsh winters would present different challenges, but the lessons learned in the Pacific about environmental factors and sustained operations would prove relevant in unexpected ways. The M1917A1’s Renaissance had established principles that transcended any individual weapon system.

The final irony was perhaps the most profound. John Moses Browning’s design philosophy emphasizing reliability and sustainability over theoretical performance had proven more relevant in 1945 than in 1917 when the gun was first produced. The intervening decades had taught the military to value complexity and sophistication. But combat had revealed the enduring importance of fundamental engineering principles that prioritized function over fashion.

Smith’s final entry in his personal log captured the essence of what the M11917A1 had taught him and the Marine Corps. The weapon had succeeded not by being the best at everything, but by being uniquely suited to specific missions that proved critical to victory. Its renaissance had demonstrated that military effectiveness came from matching tools to tasks rather than assuming that newer technology would automatically provide superior results.

The lesson extended far beyond machine guns to encompass the entire relationship between technology and tactics in modern warfare. The M19 on 17A1’s vindication had shown that combat would always be the final arbiter of military effectiveness. That battlefield requirements often contradicted peaceime assumptions and that the most important innovation sometimes involved rediscovering old solutions rather than developing new ones.

In a war defined by technological advancement, an obsolete weapon had taught the most modern lesson of all, that success came from understanding what worked rather than what should work.