On the night of July 25th, 1944 at 11:17, Seaman Firstclass Mickey Torino crouched behind a sandbagged machine gun position near the Third Medical Battalion aid station on Guam, watching Japanese infiltrators slip through the darkness towards his foxhole. At 22 years old, he was a construction worker from Brooklyn with zero confirmed kills.

Facing an enemy that had massed six battalions for a coordinated night counterattack, an assault designed to push the Marines back into the sea and overrun the soft rear areas where builders and medics worked. His M1919 30 caliber machine gun weighed 41 lbs on its tripod compared to the lightweight neortars and Aisaka rifles the Japanese snipers carried through the jungle.

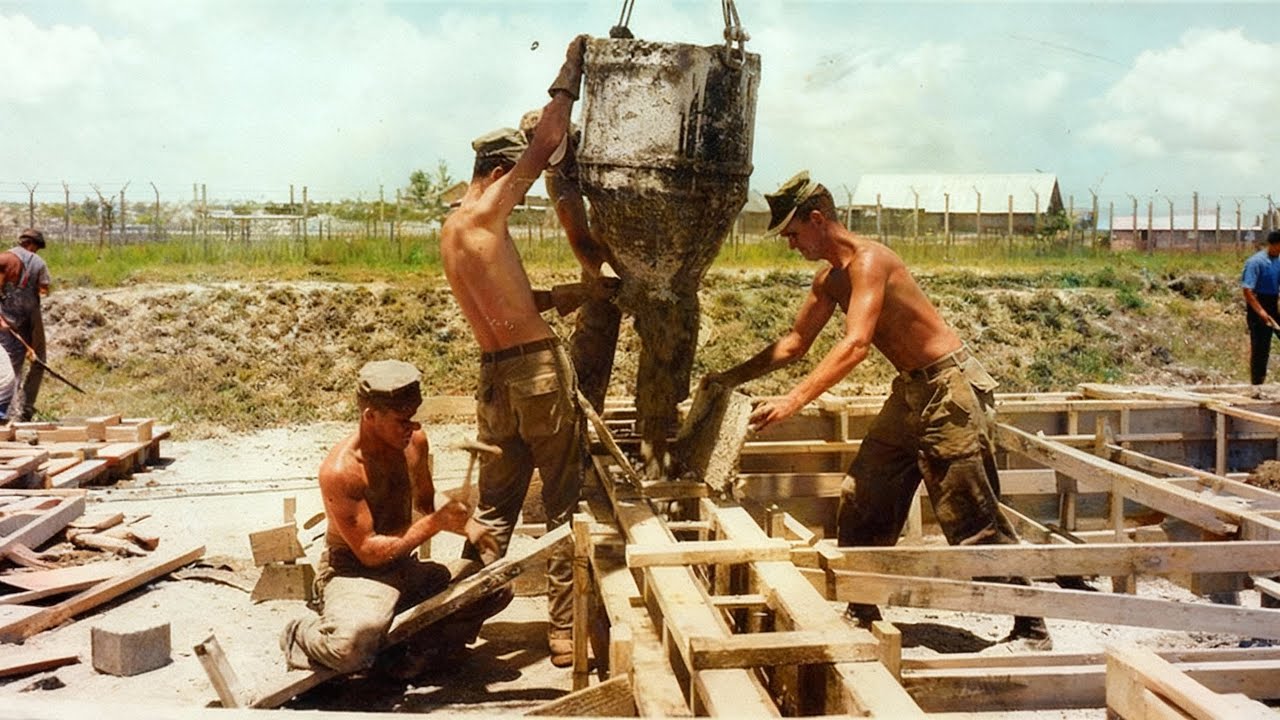

For 3 days since the landing, enemy soldiers had watched the CBS offload cargo, push dozers, and string communication wire, dismissing them as harmless construction workers who happened to wear sidearms. The Japanese called them American coolies, laborers who built runways and mixed concrete while real soldiers fought the war.

When Torino had first arrived with the second special naval construction battalion in June, even some Marines joked that the CBS were pick and shovel commandos who would run at the first sound of gunfire. They carried M1 carbines and Thompson submachine guns like combat troops, but their primary mission was steadoring supplies and building bases, not killing enemy soldiers.

Lieutenant General Teeshi Takasha, commanding the Japanese 29th Division, had studied the American beach dumps and aid stations for weeks through field glasses, noting how the rear area personnel moved supplies during daylight and dug shallow foxholes at dusk. His intelligence officers reported that the construction battalions were armed but untrained for sustained infantry combat, perfect targets for infiltration tactics that had worked against Allied rear guards throughout the Pacific.

On July 24th, Takashina issued orders for a 3,000man night assault aimed directly at the medical perimeters, ammunition dumps, and steodor positions where these construction workers had dug in. His staff calculated that once the soft rear collapsed, marine rifle companies would be cut off from resupply and medical evacuation, forcing a withdrawal to the beaches.

That night, as Japanese scouts crept within grenade range of the hospital tents and supply stacks, Commodore William Hilt received reports that his CB battalions were about to find out whether their motto meant anything. But when the enemy came for the builders, they discovered something Takasha had never planned for. The afternoon sun of July 25th, 1944 cast long shadows across the beach dumps at Assan Point as Seaman Firstclass Mickey Torino adjusted the bipod legs on his M1919 machine gun and checked the ammunition belt, feeding into the

receiver. around him. Other members of Baker Company, Second Special Naval Construction Battalion, worked methodically through their evening routine, filling sandbags, cleaning carbine actions, and testing field telephone connections to the third medical battalion command post 200 yards in land.

The routine had become familiar over the past 4 days since the initial landing, but tonight felt different. Radio chatter from regimental nets reported increased Japanese patrol activity near Mount Tenjo and unusual movement in the draws leading down from Fonte Ridge. Torino had spent three years building shipyards in Norfolk before volunteering for the CBS and his hands still carried the calluses from handling steel cable and pneumatic hammers.

The Emmy 1919 felt natural in his grip, its 41-lb weight distributed across the tripod mount in a way that reminded him of operating heavy machinery. He had qualified as expert with the weapon during training at Camp Perryi, but firing at stationary targets on a range in Virginia had little in common with what intelligence officers expected tonight.

According to briefings from Third Marine Division headquarters, Japanese forces had been probing American positions for weak points, particularly around medical installations and supply dumps where rear echelon personnel maintained lighter security. The CB battalion supporting Operation Forager had arrived with a dual mission that reflected lessons learned from earlier Pacific campaigns.

Primary responsibility remained construction and logistics, unloading LSTs, operating beach dumps, maintaining supply roads, and preparing sites for airfield construction. But every man also carried individual weapons and received infantry training because previous battles had demonstrated that Japanese tactics deliberately targeted rear areas.

The 25th and 53rd Naval Construction Battalions had been integrated directly into Third Marine Division assault echelons, while specialized detachments like Torino’s Baker Company worked closely with medical and artillery units that required immediate protection. Lieutenant Colonel Robert Kushman’s second battalion, 9inth Marines, held the line roughly 800 yards in land from the beach, where his rifle companies had spent the day consolidating positions around key terrain features and registering mortar concentrations on

likely avenues of approach. Behind Kushman’s perimeter, the medical battalion operated three aid stations in a triangular pattern designed to provide overlapping coverage for casualties from the entire northern sector. ZB machine gun teams occupied positions between these aid stations, creating interlocking fields of fire that could cover the open ground leading up from the beach dumps toward the main perimeter.

As darkness approached, Torino’s squad leader, Petty Officer Secondass Frank Kowalsski, made his rounds, checking each fighting position. Kowalsski had worked construction in Chicago before the war and understood both the capabilities and limitations of their equipment. The M1919 could sustain rates of fire up to 400 rounds per minute in short bursts with an effective range extending to 1,000 yards under ideal conditions.

However, night fighting would require careful ammunition discipline and precise range estimation, particularly since resupply might become difficult if Japanese forces succeeded in cutting communication lines between forward positions and beach dumps. Intelligence reports indicated that Lieutenant General Teeshi Tekasha commanded approximately 6,000 Japanese troops remaining on the island, organized primarily around elements of the 29th Division and various naval units that had survived the preliminary bombardment. Takasha’s tactical doctrine

emphasized night operations and infiltration tactics designed to bypass American strong points and attack supply lines, command posts, and medical facilities. Previous battles throughout the Pacific had demonstrated Japanese willingness to accept heavy casualties in exchange for disrupting American logistics networks, and Guam’s terrain provided numerous concealed approaches that could facilitate such operations.

Third Marine Division’s artillery assets included the 12th Marines with their 105 millimeter howitzers, plus core level support from 155 mm guns and even 90mm anti-aircraft weapons that could be employed in ground support roles. Brigadier General Pedro Delvier’s artillery coordination center had registered defensive fire concentrations on key terrain features and prepared illumination missions to support night defensive operations.

However, close-range fighting around medical facilities would require precise fire control to avoid friendly casualties, placing additional responsibility on individual infantry and machine gun positions. Radio communications between CB positions and regimenal headquarters maintained regular contact through the afternoon, but reports from forward observers suggested increasing Japanese activity in areas previously considered quiet.

Marine patrols had encountered enemy scouts near several key intersections, and sound detection equipment operated by artillery forward observers indicated movement in draws and ravines that offered concealed approaches toward American rear areas. The pattern suggested coordination rather than random probing, implying that Japanese forces were conducting final reconnaissance before launching a larger operation.

Commodore William Hilt, commanding the fifth naval construction brigade, had positioned his battalions according to plans developed during rehearsals in Hawaii. Construction personnel would continue normal operations during daylight hours, but transition to defensive positions at dusk, creating a secondary perimeter behind marine rifle companies.

This arrangement allowed maximum utilization of available manpower while maintaining essential logistics functions. However, success depended on individual CB units demonstrating proficiency with infantry weapons and tactics under combat conditions they had trained for but never experienced. As the sun dropped toward the horizon, casting the beach area into shadow, Torino chambered around in his machine gun and adjusted the traversal and elevation controls one final time. around him.

Other CBS completed their preparations, checking ammunition loads, testing field telephones, and reviewing range cards that identified key terrain features and distance estimates. The familiar sounds of construction work had given way to the quiet efficiency of soldiers preparing for battle. While radio reports continued to indicate Japanese movement toward American positions, within hours, Lieutenant General Takasha’s counterattack would test whether the motto, “We build, we fight,” represented training doctrine or combat

reality. At 2300 hours on July 25th, hospital corman secondass Daniel Murphy heard the first grenade detonate 60 yards from the third medical battalion’s main aid station, followed immediately by the distinctive crack of an Arisaka rifle firing from somewhere in the darkness beyond the perimeter wire. Murphy had been checking supplies in the surgical tent when the explosion sent him diving behind a stack of plasma bottles, his M1 carbine already in his hands as training took over.

Through the canvas walls, he could hear petty officer Kowalsski shouting range and direction to the CB machine gun teams positioned around the medical compound. Their voices cutting through the sudden chaos of men scrambling for fighting positions. The Japanese infiltration had begun exactly as intelligence officers had predicted with small teams armed with knee mortars and grenades probing for weak points in the American defensive network.

However, Lieutenant General Takasha’s forces had underestimated both the density of defensive positions around the medical facilities and the combat readiness of personnel they had dismissed as non-combatants. Seaman Torino opened fire with his M1919 machine gun at a muzzle flash he spotted near a cluster of palm trees.

His tracer rounds arcing across the beaten zone in controlled three round bursts that swept a 60-yard arc. According to his predetermined range card, the type 89 knee mortar that had announced the attack represented standard Japanese infantry tactics for night operations. Lightweight, portable, and capable of delivering 50 mm projectiles at ranges up to 700 yardds with reasonable accuracy.

However, the weapon’s effectiveness depended on concealment and mobility, advantages that disappeared once American defensive fires began ranging on the source of each shot. Murphy watched from his position behind the aid station as illumination rounds from the 12th Marines 105mm howitzers burst overhead, casting harsh shadows across the compound and revealing at least six Japanese soldiers moving through the brush toward the hospital tents.

Corman Murphy had completed infantry training at Camp Leune before specialized medical instruction, and his carbine represented a compromise between firepower and portability, suitable for medical personnel who needed to move quickly between casualties while maintaining defensive capability. The M1 Carbine fired a 30 caliber cartridge from a 15 round magazine with an effective range of 200 yards and a cyclic rate allowing rapid semi-automatic fire against infiltrators operating at ranges under 100 yards. The

weapon provided adequate stopping power while remaining light enough for extended carrying during casualty evacuation missions. Japanese tactics emphasized stealth and coordination with individual teams assigned specific objectives within the medical complex. aid stations, surgical facilities, ammunition storage areas, and communication centers.

However, American defensive planning had anticipated such approaches and positioned interlocking fields of fire to cover all likely avenues of advance. When the first Japanese team attempted to rush the main aid station, they encountered crossfire from Thompson submachine guns operated by CB security teams positioned on both flanks of their approach route.

The Thompson submachine gun proved particularly effective in close-range defensive fighting around the medical perimeter. Chambered for the 45 caliber pistol cartridge and feeding from either 20 or 30 round magazines, the weapon delivered devastating firepower at ranges under 50 yards while remaining controllable in the hands of personnel who lacked extensive infantry experience.

Petty Officer Kowalsski had positioned his Thompson teams to cover the narrow lanes between medical tents, creating killing zones where Japanese infiltrators would be forced to expose themselves while attempting to reach their objectives. Artillery support from Brigadier General Delvalier’s coordination center provided both illumination and high explosive fires on call, but proximity to friendly positions required careful fire control to prevent casualties among American defenders.

Forward observers attached to the medical battalion maintained radio contact with firing batteries, calling for illumination rounds timed to burst at predetermined altitudes and locations that would backlight Japanese movement without compromising American night vision. When concentrations of enemy personnel were identified beyond minimum safe distances, high explosive rounds from 105 mm howitzers delivered fragmentation effects across beaten zones calculated to neutralize personnel in the open. The fighting around the aid

stations intensified after midnight as additional Japanese teams attempted to exploit gaps they perceived in the American defensive network. However, these gaps represented deliberate channels designed to funnel attackers into predetermined killing zones where multiple weapons could engage simultaneously.

When a team of eight Japanese soldiers attempted to approach the surgical tent from the northeast, they encountered interlocking fire from two M1919 machine guns and a 60mm mortar crew that had registered concentrations on that specific approach route during daylight reconnaissance. Hospital corman Murphy found himself treating casualties while simultaneously engaging targets of opportunity.

A dual mission that reflected the reality of defensive combat in rear areas where medical personnel could not remain non-combatants. His first patient arrived at 2345 hours. A CB machine gunner with shrapnel wounds from a knee mortar round that had detonated near his position. While applying pressure dressings and administering morphine, Murphy maintained visual contact with his assigned sector of responsibility, ready to engage any Japanese soldiers who might approach the aid station during the treatment process. The Japanese type

99 rifle employed by enemy snipers chambered the 7.7 mm cartridge and featured a relatively low muzzle flash that made source detection difficult in darkness. However, American defenders had prepared for this threat by positioning multiple observation points that could triangulate on sniper positions through sound and muzzle flash detection.

When Japanese marksmen attempted to engage stretcher bearers moving between aid stations, they exposed themselves to return fire from carbines and Thompson submachine guns that delivered superior rates of fire at the ranges involved. By 0300 hours, organized Japanese resistance around the medical perimeter had collapsed under sustained defensive fires and heavy casualties.

Body counts conducted at first light would reveal 33 enemy dead in the immediate vicinity of the third medical battalion facilities, representing the destruction of approximately one reinforced platoon that had been specifically tasked with overrunning American medical capabilities. American casualties totaled three killed in action and 20 wounded in action with two additional personnel dying of wounds within 24 hours, demonstrating both the intensity of the fighting and the effectiveness of prepared defensive positions manned by personnel who had trained extensively

for exactly this type of engagement. At midnight on July 26th, machinists mate first class Tony Benadetto crouched behind a bulldozer parked near the Agot beach dumps, watching Japanese infiltrators moved through the drainage ditch that ran parallel to the main supply road toward Arodi Peninsula. His Thompson submachine gun rested across the dozer’s track.

It’s 30 roundy magazine loaded with 45 caliber ammunition that would prove devastatingly effective at the ranges he expected to encounter. around him. Other members of the 25th Naval Construction Battalion had abandoned their daytime roles as steadors and equipment operators to man defensive positions protecting the critical supply dumps that fed Brigadier General Shepherd’s assault on the airfield.

The southern sector’s tactical situation differed significantly from the medical perimeter fighting at Asen with Japanese forces attempting to sever supply lines rather than overrun fixed facilities. Intelligence reports indicated that elements of the Japanese 38th Infantry Regiment had been tasked with disrupting ammunition and fuel stockpiles that supported the first provisional marine brigades advance toward a road.

However, CB defensive planning had anticipated such tactics and positioned interlocking fields of fire to cover the road junctions and equipment parks where enemy infiltrators would be forced to expose themselves while attempting to reach their objectives. Benadetto had operated heavy equipment in Detroit shipyards before volunteering for overseas service, and his familiarity with industrial machinery translated directly to understanding the tactical importance of the equipment he now defended. The DUKW amphibious trucks

parked in neat rows behind his position represented the primary means of moving supplies from ship to shore across the reef, while bulldozers and graders provided essential road maintenance capabilities that kept supply routes open despite damage from enemy artillery and tropical weather. Japanese destruction of this equipment would force manual handling of supplies and significantly reduce the tonnage rates required to sustain offensive operations.

The Japanese approach relied on small teams armed with satchel charges and incendiary devices designed to destroy vehicles and fuel storage areas through coordinated attacks that would maximize damage while minimizing exposure to American defensive fires. However, this tactical approach required precise timing and coordination that proved difficult to maintain under the harassment fires that core artillery had been delivering on suspected assembly areas throughout the evening.

When the first enemy team attempted to reach the DUKW Park, they encountered carefully planned crossfire from Thompson submachine guns and M1 carbines that had been zeroed on specific ranges during daylight preparation. The Thompson’s effectiveness in close-range defensive combat around supply dumps reflected both its firepower characteristics and the tactical requirements of the engagement.

At ranges under 50 yards, the 45 caliber cartridge delivered sufficient stopping power to neutralize targets immediately, while the weapon’s high cyclic rate allowed rapid engagement of multiple targets within a confined area. Benadetto had positioned himself to cover the northeastern approach to the equipment park, where drainage ditches and scattered palm trees provided concealment for infiltrators, but also channeled their movement into predetermined killing zones.

Artillery support for the southern sector came primarily from the army’s 105th millimeter howitzer battalions that had been allocated to support the first provisional marine brigades operations. These weapons provided both illumination and high explosive fires on call, but their effectiveness depended on forward observers who could maintain visual contact with targets while coordinating with defensive positions to prevent fratricidal casualties.

When Japanese concentrations were identified beyond minimum safe distances, timed concentrations delivered fragmentation effects calculated to neutralize personnel in the open while avoiding damage to American equipment and supplies. The fighting intensified after 0 hours as additional Japanese teams attempted to exploit what they perceived as gaps in the American defensive network.

However, these gaps represented carefully planned fire lanes designed to channel attackers into areas where multiple weapons could engage simultaneously. When a reinforced squad of Japanese soldiers attempted to approach the fuel dump from the southwest, they encountered coordinated fires from two M1919 machine guns and a 60mm mortar crew that had registered concentrations on that specific approach route.

Seaman Firstclass James Okconor, operating an M1919 machine gun from a position overlooking the main supply road, maintained precise fire discipline while engaging targets at ranges between 100 and 300 yards. His weapons tripod mount provided the stability necessary for accurate fire at extended ranges, while the sustained rate of fire capability allowed him to sweep beaten zones that covered multiple lanes of approach simultaneously.

The interlocking nature of these defensive fires created a network of coverage that prevented Japanese forces from massing for coordinated attacks while exposing individual infiltrators to devastating crossfire. Japanese tactics evolved throughout the night as enemy commanders recognized the effectiveness of American defensive preparations and attempted to adapt their approach accordingly.

Suicide rush’s designed to overwhelm defensive positions through shock and momentum replaced the earlier emphasis on stealth and infiltration. But these tactics proved even more costly when employed against prepared positions with interlocking fields of fire. The first provisional marine brigades military police companies provided additional security for critical supply nodes, creating multiple layers of defense that forced Japanese attackers to expose themselves repeatedly while approaching their objectives. The 60mm mortar proved

particularly valuable for engaging targets in dead space that could not be reached by direct fire weapons operated by twoman crews that included personnel cross-trained from construction specialties. These weapons delivered high explosive and illumination rounds at ranges up to 2,000 yd with accuracy sufficient for close support missions.

When Japanese forces attempted to mass in a draw approximately 800 yd from the beach dumps, mortar concentrations dispersed the formation and forced survivors into areas covered by machine gun and rifle fire. Brigade artillery coordination became critical as the intensity of fighting increased with forward observers calling for illumination rounds timed to backlight Japanese movement while avoiding interference with American night vision equipment.

The effectiveness of these fires depended on precise timing and coordination between multiple firing units requiring communication discipline and fire control procedures that had been practiced extensively during training but never tested under combat conditions. When properly executed, these techniques created conditions that favored American defensive tactics while negating Japanese advantages in night fighting and local terrain knowledge.

By 0400 hours, organized resistance around the AGOT supply dumps had been neutralized through a combination of defensive fires and heavy casualties among attacking forces. Morning reconnaissance would reveal evidence of a coordinated attack involving approximately two companies of Japanese infantry with casualty ratios heavily favoring American defenders who had utilized prepared positions and superior firepower to defeat numerically superior forces.

The successful defense of these critical supply facilities ensured continued support for offensive operations toward Orote while demonstrating the combat effectiveness of construction personnel operating in infantry roles. At 0330 hours on July 26th, Lieutenant General Teeshi Tekasha realized his coordinated counterattack was collapsing as radio reports from his subordinate commanders painted a picture of mounting casualties and failed objectives across both northern and southern sectors.

From his command post in a cave complex near Fonte Ridge, Takasha could hear the sustained firing from American defensive positions that indicated his infiltration teams were encountering organized resistance rather than the soft targets his intelligence staff had predicted. The 18th Infantry Regiment’s assault toward the Assan valleys had stalled under murderous crossfire from positions that should have been lightly defended.

While reports from the 38th Infantry Regiment indicated similar problems around the erot supply dumps, Major General Alan Turnage commanding the third marine division coordinated the northern sector’s response from his command post near Adelaup Point where radio communications provided real-time updates on the fighting around medical facilities and supply dumps. turnages.

Tactical reserves included elements of the 21st Marines that had been held in readiness for exactly this type of situation, but reports from subordinate commanders indicated that existing defensive positions were containing enemy penetrations without requiring additional reinforcements. The integration of CB battalions into the defensive network was proving more effective than pre- battle planning had anticipated with construction personnel demonstrating proficiency with infantry weapons and tactics that negated

Japanese advantages in night fighting. The Japanese assault on a Rot Peninsula represented Takasha’s most ambitious objective designed to recapture the airfield and cut off American forces advancing along the southern coast. However, the 22nd Marines under Colonel John Lanigan had established defensive positions that covered all likely avenues of approach, while coordination with CB perimeters around supply dumps created interlocking fields of fire that channeled Japanese attackers into predetermined killing zones. When

elements of the second battalion 38th infantry regiment attempted to penetrate marine lines near the rifle range, they encountered coordinated fires from multiple weapon systems that had been registered on those specific terrain features during daylight reconnaissance. Artillery coordination under Brigadier General Delval reached its peak effectiveness during the pre-dawn hours as forward observers called for mass fires on Japanese assembly areas and approach routes.

The Third Marine Division’s organic artillery included three battalions of 105 mm howitzers capable of delivering sustained fires at ranges exceeding 11,000 yards. While core level support provided additional firepower from 155 mm guns and even 90mm anti-aircraft weapons employed in ground support roles.

These weapons delivered approximately 26,000 rounds during the night’s fighting, creating a wall of steel that prevented Japanese forces from massing for coordinated attacks while inflicting casualties that degraded combat effectiveness across multiple enemy units. The 90mm anti-aircraft guns proved particularly effective when employed against ground targets.

Their high muzzle velocity and flat trajectory characteristics making them ideal for engaging personnel and light fortifications at extended ranges. Operated by the 14th Defense Battalion, these weapons fired both high explosive and proximity fused rounds that detonated above ground level to maximize fragmentation effects against troops in the open.

When Japanese forces attempted to mass in the draws leading down from Fonte Ridge, 90 mm concentrations delivered devastating casualties that forced survivors to disperse an abandoned coordinated movement toward American positions. Lieutenant Colonel Kushman’s second battalion, 9inth Marines, maintained pressure along the northern perimeter while coordinating closely with CB defensive positions that protected his flanks and rear areas.

Kushman’s tactical philosophy emphasized aggressive patrolling and immediate counterattacks against enemy penetrations, preventing Japanese forces from consolidating gains or establishing positions that could threaten American supply lines. When reports indicated enemy movement toward the third medical battalion facilities, Kushman dispatched reinforced squads to coordinate with CB defenders and ensure that medical capabilities remained operational throughout the night’s fighting.

Japanese naval forces under Captain Utaka Sugimoto attempted to coordinate with army units by launching simultaneous attacks from positions near Cabras Island, but these efforts proved ineffective against prepared American defensive positions that covered water approaches as well as land routes. The integration of different Japanese service branches suffered from communication problems and conflicting tactical doctrines that prevented effective coordination.

While American forces benefited from unified command structures and standardized procedures that had been tested during previous amphibious operations throughout the Pacific, tank support became available to American defenders as M4 Sherman tanks from the third tank battalion moved forward to reinforce threatened sectors.

Their 75 millimeter main guns providing direct fire support against Japanese strong points that could not be neutralized by infantry weapons. These tanks employed both high explosive and canister rounds designed specifically for anti-personnel effects, creating additional casualties among Japanese forces attempting to mass for final assaults before daylight.

The mobility and firepower of armored vehicles proved decisive in several engagements where Japanese forces had achieved temporary penetrations of American defensive lines. Communication between defensive positions relied heavily on field telephone networks that had been installed during the previous day’s preparation, supplemented by radio communications when wire lines were severed by enemy action or artillery fires.

The reliability of these communication systems allowed for rapid coordination of defensive fires and immediate response to enemy penetrations, capabilities that Japanese forces lacked due to their reliance on runners and pre-planned signals that could not adapt to changing tactical situations. American commanders could redirect artillery fires, call for reinforcements, and coordinate counterattacks within minutes of identifying enemy threats.

The climactic phase of Takasha’s counterattack occurred during the hour before dawn when surviving Japanese forces launched desperate final assaults designed to achieve breakthrough before American air support became available. However, these attacks encountered defensive positions that had been reinforced throughout the night and supported by artillery concentrations that had been precisely registered on all likely approach routes.

The 22nd Marines defense of a wrote peninsula epitomized American tactical superiority with interlocking fields of fire that prevented enemy penetrations while inflicting casualties that exceeded Japanese replacement capabilities. By 0500 hours, organized Japanese resistance had collapsed across both northern and southern sectors with surviving enemy forces beginning withdrawals toward prepared positions in the island’s interior.

Morning reconnaissance would reveal approximately 3,500 Japanese casualties from the nights fighting, representing the destruction of three enemy battalions in the effective end of organized resistance capable of threatening American rear areas. The failure of Takasha’s counterattack marked the decisive turning point in the battle for Guam, demonstrating that American defensive capabilities exceeded Japanese offensive doctrine while validating the integration of construction personnel into combat operations. Dawn on July 26th revealed

the aftermath of Lieutenant General Takasha’s failed counterattack across the beaches and supply dumps of Guam, where the bodies of Japanese soldiers lay scattered among ammunition crates and medical tents that had been defended throughout the night by personnel originally trained for construction rather than combat.

Seaman Firstclass Mickey Torino stood beside his M1919 machine gun position, counting 33 enemy dead within the third medical battalion’s perimeter alone. While around him, other CBS began the methodical process of clearing weapons and checking equipment that would soon return to its primary mission of building the infrastructure required for Pacific Fleet operations.

The transformation from defenders back to builders began immediately as Commodore Hiltabiddol’s Fifth Naval Construction Brigade received orders to resume construction projects that had been interrupted by the Knights fighting. However, the priorities had shifted significantly based on tactical lessons learned during the Japanese assault and the recognition that rear area security remained a critical requirement even after organized enemy resistance had been neutralized.

The same personnel who had operated machine guns and mortars during darkness now began preparing construction sites for projects that would transform Guam into the forward naval base that Admiral Nimmits required for operations against the Japanese home islands. Within 48 hours of the counterattack’s failure, Marine and Army units had eliminated organized resistance around Fonte Ridge and completed the capture of Orote Peninsula, validating the tactical decision to hold rear area positions rather than commit reserves to premature offensive operations.

The Japanese forces that had survived Tekkashina’s assault withdrew toward prepared positions in the northern mountains, but their combat effectiveness had been degraded to the point where they pose little threat to American construction activities or supply operations. Lieutenant General Takasha himself was killed on July 28th while attempting to coordinate withdrawals near Fonte, effectively ending centralized Japanese command and control on the island.

The construction projects that followed demonstrated the dual nature of CB capabilities that had proven so effective during the night fighting. Pontoon Pier construction at Cabers Island began on August 5th under the direction of the same personnel who had defended supply dumps against Japanese infiltrators with the first operational pier completed on August 22nd.

Despite continued harassment from scattered enemy snipers operating in the surrounding jungle, these facilities provided the deep water birthing capacity required for large naval vessels and cargo ships that could not navigate the shallow reef areas around the main beaches. Engineering projects undertaken by the Naval Construction Battalions included the glass breakwater that protected Opera Harbor from typhoon damage, road construction projects that connected military installations across the island, and airfield preparation

that would accommodate B-29 bombers for operations against Japan. The personnel who completed these projects carried the same weapons they had used during defensive operations with security details maintaining constant vigilance against Japanese stragglers who continued to pose threats to construction crews working in isolated areas.

The tactical integration that had proven so successful during the night fighting continued throughout the construction phase with Marine security detachments working closely with CB battalions to provide protection for critical projects while maintaining the flexibility to respond to intelligence reports of enemy activity. This coordination reflected lessons learned not only from the July 26th counterattack, but from previous Pacific campaigns where Japanese forces had demonstrated willingness to sacrifice personnel in attacks designed to delay

American construction schedules rather than achieve decisive tactical victories. Statistical analysis of the Knights fighting provided validation for pre-war doctrinal decisions regarding the training and equipment of Naval Construction Battalion personnel. American casualties totaled 166 killed in action, 645 wounded in action, and 34 missing in action across the Third Marine Division alone during the period from July 25th through 27th, demonstrating the intensity of combat that construction personnel had been

expected to survive while maintaining their primary engineering mission. Japanese losses exceeded 3,500 killed during the same period with casualty ratios heavily favoring American forces that had utilized superior firepower and defensive tactics. The strategic implications of successful rear area defense extended far beyond the immediate tactical situation on Guam as the island’s rapid transformation into a major naval and air base validated strategic planning that depended on construction capabilities surviving

combat operations. Within six months, facilities constructed by the same CB battalions that had defended medical stations and supply dumps were supporting fleet operations against Euoima and Okinawa, while B29 bombers operating from Guam based airfields conducted strategic bombing missions against Japanese industrial targets.

Marine Corps Drive, constructed by CB Battalions during August and September 1944, connected military installations across the island while providing evidence of the construction capability that had been preserved through effective defensive operations. The road required extensive grading and bridge construction through terrain that remained contested by Japanese stragglers, necessitating continued coordination between construction crews and security detachments that maintain the tactical procedures developed during

the initial assault phase. Personnel rotation policies implemented during the construction phase recognized the dual training requirements that had proven essential for successful operations with newly arrived CB replacements receiving both technical instruction in construction techniques and tactical training in infantry weapons and defensive procedures.

This integration reflected institutional learning that validated pre-war decisions regarding the combat training of construction personnel while identifying areas where additional emphasis was required for future operations. The airfield construction projects undertaken at Ot Peninsula and other locations across Guam required extensive coordination with military police units and intelligence personnel who provided information regarding Japanese capabilities and intentions.

Construction crews worked under constant security alert while maintaining production schedules that supported strategic timelines for subsequent operations, demonstrating the operational flexibility that had been achieved through effective integration of construction and combat capabilities. By December 1944, facilities constructed by naval construction battalions on Guam were supporting major fleet operations throughout the Western Pacific with harbor facilities, airfields, supply depots, and communication centers

providing the infrastructure required for sustained operations against Japanese strongholds. The personnel who had defended these facilities during their initial construction continued to provide security and maintenance support, creating an integrated system that validated the doctrinal concept of construction units capable of fighting when necessary while maintaining their primary engineering mission.

The legacy of the July 26th counterattack extended beyond immediate tactical success to encompass strategic validation of amphibious warfare doctrine that depended on rapid construction of advanced bases capable of supporting sustained operations. When the enemy came for the builders, they discovered that American construction workers were prepared to fight and that preparation made the difference between strategic success and potential failure in the Pacific War’s decisive phase.