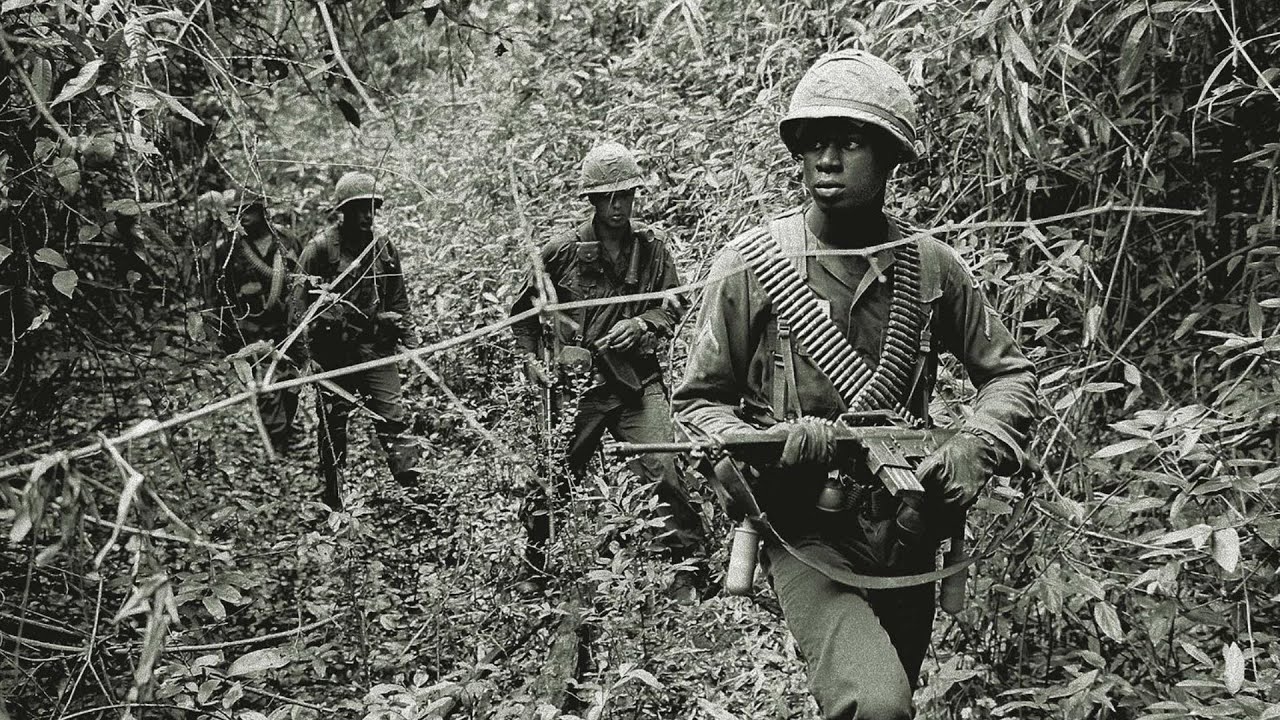

September 14th, 1969, 3 in the morning. A Vietkong radio operator grabs his transmitter with shaking hands and screams seven words that American intelligence would keep classified for the next 40 years. The forest is eating us alive. And then silence. 23 battleh hardened guerilla fighters, veterans who had survived Napalm, B-52 carpet bombing, and years of jungle warfare gone, vanished.

No bodies, no graves, no trace. Just those seven terrifying words hanging in the darkness. What happened to them? Who or what hunted them down one by one over 72 hours of pure terror? The answer will shock you because this was not the Vietkong’s jungle anymore. This was Australian SAS territory.

And what those 12 operators did to unit D445 remains one of the most disturbing, most controversial, and most deliberately buried chapters of the entire Vietnam War. The Pentagon tried to hide it. Official histories pretend it never happened. But today we are pulling back the curtain on the men the Vietnamese called quote one the jungle ghosts.

Soldiers who moved so silently they could stand within arms reach of the enemy without being detected. Warriors who used ancient Aboriginal hunting techniques to turn human beings into prey. Operators whose methods were so effective and so terrifying that American commanders refused to officially acknowledge them.

Why did they cut the boots of their victims? What was the meaning of those strange ration packs left beside the bodies like ritual offerings? And how did a handful of Australians achieve a kill ratio that made the mighty US special forces look like amateurs? Stay with me until the end because what you are about to hear will change everything you thought you knew about Vietnam and about what happens when warriors become something more than human. Let’s begin.

The message crackled through the humid night air of Fuaktui province at exactly 0300 hours on the morning of September 14th, 1969. A Vietkong radio operator, his hands trembling so violently he could barely hold the transmitter, spoke seven words that would be recorded, translated, and classified by American intelligence for the next four decades.

Quote two. Then silence. absolute complete terrifying silence. The entire unit, 23 hardened guerilla fighters who had survived bombing campaigns, chemical defoliation, and countless firefights with American Marines, simply vanished from the face of the earth. No bodies recovered by their comrades.

No prisoners taken by Allied forces, no graves discovered in the decades since. But those seven words were only the end of the story. What happened in the 72 hours before that transmission would remain classified for decades and for good reason. This was no supernatural phenomenon. This was not the jungle claiming victims through disease or accident.

This was something far more calculated, far more methodical, and far more terrifying. This was the work of a 12-man patrol from the Australian Special Air Service Regiment. and what they did to unit D445 represents one of the most chilling, most controversial, and most deliberately suppressed chapters of the entire Vietnam War.

The Americans had a saying in Vietnam. They said the jungle belonged to Charlie. The Vietkong moved through the triple canopy rainforest like ghosts, appearing from nowhere, striking with devastating precision, then melting back into the green darkness before air support could be scrambled. For years, this was accepted military reality.

The enemy owned the night. The enemy owned the bush. But the Australians never accepted this reality. And what they did about it would change everything. The unit that sent that final desperate transmission was designated D445 in Vietkong organizational records. They were not amateurs. They were not local militia pressed into service.

These were experienced fighters from the 274th regiment, veterans of the Ted offensive, survivors of Operation Cobberg, men who had watched American battalions stumble through the jungle like blind elephants while they picked off stragglers at will. their commander, a 34year-old political officer known only by his nom dear three had personally overseen the elimination of 11 South Vietnamese village chiefs and had evaded capture for six consecutive years.

His men feared nothing in the forest. They were about to learn how wrong they were. The first indication that something had changed came at dusk on September 11th. A scout moving ahead of the main column simply failed to return. This was not unusual in itself. Scouts sometimes encountered enemy patrols, sometimes triggered booby traps, sometimes simply got lost in the maze of identical vegetation.

Brother Min ordered the column to halt and sent two men back along the trail to locate their missing comrade. Neither man returned. No shots were heard. No explosions echoed through the canopy. The jungle simply swallowed them whole. But here is where the story takes its first disturbing turn. What brother Min did not know, what he could not possibly have known was that his unit had been under continuous surveillance for the previous 19 days.

A four-man Australian SAS reconnaissance team operating under radio silence so complete they had not transmitted a single message in nearly 3 weeks had been tracking D445 since the unit crossed from their sanctuary in the Long High Hills. The Australians had watched them eat. They had watched them sleep.

They had memorized their patrol patterns, their rest schedules, their latrine habits. They knew which men snorred. They knew which men talked in their sleep. And 19 days of watching was only the preparation phase. The Australian method was something American forces had never seen and could barely comprehend. While US doctrine emphasized overwhelming firepower, artillery barges, air strikes, helicopter gunships, the Australians operated on principles that seemed to belong to a different century entirely.

Their patrols moved so slowly through the jungle that they could take 8 hours to cover 400 m. They never walked on trails. They never broke branches. They never left bootprints in soft mud. They communicated entirely through hand signals, sometimes going 72 hours without speaking a single word aloud. But it was their psychological approach that truly set them apart.

And it was about to be unleashed with devastating effect. The Australians understood something that American commanders never grasped. They understood that the Vietkong’s greatest weapon was not their AK-47s or their booby traps or their tunnel networks. Their greatest weapon was their belief that the jungle protected them.

Destroy that belief and you destroyed the fighter. So the Australians set about destroying that belief with systematic almost scientific precision. The missing scout was found by brother men’s search party at first light on September 12th. Or rather parts of him were found. His body had been positioned, there is no other word for it, against a tree trunk in a sitting position, hands folded neatly in his lap.

His boots had been removed and placed beside him with military precision. His weapon was gone. His ammunition was gone. But most disturbing of all was what had been left behind. A single Australian ration pack, unopened, had been placed on his chest like an offering. The message was unmistakable. We were here. We watched you find him. We are still watching.

But this gruesome discovery was merely the opening move in a much larger game. The effect on the surviving Vietkong fighters was immediate and devastating. These were not superstitious peasants, but hardened ideological warriors trained to resist psychological manipulation. Yet within hours of finding their comrade, unit cohesion began to fracture.

Three men refused to move from the discovery site, insisting the group remained together until daylight. Two others demanded an immediate forced march to the nearest friendly village, abandoning all tactical protocols. Brother Min, despite his years of combat leadership, found himself unable to project the calm authority his position required, and the Australians had not yet revealed their most terrifying capability.

American intelligence officers would later describe what happened over the next 48 hours as quote four, a clinical phrase that utterly fails to capture the primal terror experienced by the men of D445. The Australians did not simply hunt their enemy. They systematically dismantled their enemy’s perception of reality itself.

On the night of September 12th, the Vietkong unit established a defensive perimeter in a small clearing, posting sentries at four cardinal points. Standard doctrine, standard positioning. They had executed this drill hundreds of times. But when dawn broke on September 13th, everything they knew about warfare would be shattered.

Each of the four centuries was found in exactly the same position they had assumed. the night before. Same posture, same weapon placement, same orientation, except that each man had been rendered permanently unconscious without a single shot being fired, without a single cry of alarm being raised. Their boots had been cut, not removed, but surgically sliced in a distinctive pattern that would later be identified as an Australian SAS signature.

And beside each man, that same unopened ration pack. Think about what this means from a psychological perspective. 23 trained guerilla fighters sleeping in defensive formation had been penetrated four separate times during a single night. Four centuries had been neutralized within meters of their sleeping comrades.

And not one of the remaining 19 men had heard anything. Not a footstep, not a rustle, not a whisper. The Australians might as well have been ghosts, but they were something far worse than ghosts. Brother Min, to his credit, attempted to restore order. He gathered his remaining fighters and delivered what survivors would later describe as an impassioned speech about revolutionary duty and the inevitability of socialist victory.

He reminded them that they had faced B 52 bombing raids. They had survived Napalm. They had endured chemical defoliation that stripped the protective jungle bear. They would not be intimidated by a handful of foreign soldiers playing mind games in the dark. But even as he spoke, something was happening that none of them noticed.

The Australians, and this detail comes from declassified afteraction reports that would remain sealed until 2012, were actually within the perimeter during the speech. Two SAS operators had infiltrated so close to the assembled Vietkong that they could have reached out and touched the nearest fighter. They watched, they listened, they counted heads and noted weapons.

Then they withdrew without disturbing a single leaf. Brother Min’s inspiring speech was delivered to an audience that included his own hunters. The following night brought the technique known among Australian operators as quote five. Its origins traced back to Aboriginal hunting methods adapted for modern warfare.

The concept was devastatingly simple. Humans in a state of fear become hypervigilant. They strain to hear every sound. Their minds begin to fill silence with phantom noises. The Australians exploited this with precision that bordered on cruelty. A barely audible footstep that might have been a falling branch, a whisper that might have been wind through leaves, a shadow that moved at the edge of peripheral vision, but vanished when directly observed.

The Vietkong unit spent the entire night of September 13th in a state of escalating terror, firing at phantoms, challenging empty darkness, slowly exhausting themselves physically and psychologically. And then came the rain. The moment the Australians had been waiting for. Monsoon season in Fuaktui province transforms the jungle into something that seems actively malevolent.

Water pours from the sky and sheets so thick that visibility drops to mere meters. The noise is deafening. A constant roar that drowns all other sound. The ground becomes a sucking morass that swallows boots and weapons and men. Most military units on both sides of the conflict simply ceased operations during monsoon downpours.

But the Australians had spent months training specifically for monsoon operations. They knew that the noise of rainfall provided perfect acoustic cover. They knew that reduced visibility favored small, highly trained teams over larger conventional units. They knew that enemy fighters would be psychologically primed to let their guard down, to assume that no one would be moving in such conditions.

What happened during the storm of September 14th has never been fully documented and perhaps it never will be. The Australian afteraction reports describe it with clinical brevity. Quote six. But the intercepted radio transmission tells a different story. It tells a story of men being taken one by one from the edges of a huddled group.

It tells a story of survivors hearing nothing but rain, then suddenly discovering another empty space where a comrade had been sitting moments before. It tells a story of 23 fighters reduced to seven, then to three, then to a single radio operator desperately keying his transmitter. The forest is eating us alive.

Those seven words were not a metaphor. They were a precise description of what was happening. But the story behind those words stretches back far beyond that single night. The Americans who eventually reviewed this operation had a complicated reaction. On one hand, how the Australian SAS had achieved something remarkable.

A 12-man patrol, later revealed to consist of two separate six-man teams operating in coordination, had effectively eliminated an entire enemy company over the course of 72 hours. They had done so without air support, without artillery, without the massive logistical infrastructure that American operations required. But there were aspects of the operation that made American observers deeply uncomfortable.

The cut boots, for instance, served no tactical purpose that US analysts could identify. They appeared to be purely psychological, a calling card, a signature, a message to any Vietkong unit that might find the bodies. The positioning of the eliminated fighters, likewise, seemed designed for maximum psychological impact rather than tactical necessity.

and the use of those ration packs, left like strange offerings beside each neutralized enemy, struck American officers as almost ritualistic. Then there were the things that Australian operators refused to discuss at all. When American intelligence officers attempted to debrief the SAS teams involved in the operation, they encountered a wall of silence that no amount of Allied cooperation protocols could penetrate.

The Australians would confirm basic facts, dates, locations, force numbers, but anything related to specific techniques was met with flat refusal. Quote, seven. One Australian sergeant reportedly told an exasperated American colonel. Quote, 8. This response infuriated American commanders, but their frustration was about to become something closer to humiliation.

The US military had invested billions of dollars in the Vietnam War. They had deployed half a million troops at the conflict’s peak. They had the most advanced weapons technology on Earth. And yet, a tiny contingent of Australians, never more than a few hundred SAS operators in country at any given time, was achieving results that made American special forces look almost amateur-ish by comparison.

The numbers told a devastating story. During the entire Vietnam War, Australian SAS suffered 17 personnel lost in action while operating in Puaktoy province. In that same period, they accounted for an estimated 500 enemy fighters eliminated through direct action, a kill ratio that dwarfed anything American units could claim.

More importantly, their mere presence in an area caused Vietkong activity to plummet. Intelligence intercepts repeatedly showed enemy commanders ordering units to avoid the Maung, the jungle ghosts, at all costs. But perhaps the most telling statistic was one that American planners found almost impossible to believe. During major operations, US forces typically required between 50,000 and 100,000 rounds of ammunition expended per confirmed enemy casualty.

The Australians averaged less than 200 rounds per elimination. They were not simply more efficient. They were operating according to an entirely different philosophy of warfare. And the origins of that philosophy would shock American military thinkers to their core. The training methods that created the Maung traced back to the years immediately following World War II when the Australian military faced a stark reality.

They would never match American or Soviet force numbers. They would never have unlimited budgets for advanced weapons systems. they would never be able to conduct the kind of industrial-cale warfare that larger powers took for granted. So they focused instead on creating the most highly skilled individual operators in the world.

The selection process for Australian SAS was and remains among the most demanding on Earth. Candidates faced a 3-week selection course designed not simply to test physical endurance, but to identify those individuals capable of functioning independently in hostile environments for extended periods. The wash out rate consistently exceeded 80%.

Those who survived selection then underwent two years of additional training before being considered operational. But it was the nature of that training that truly set the Australians apart. And it involved a partnership that no western military had ever attempted. They trained with Aboriginal trackers.

They learned to read the bush the way most people read books. They studied animal behavior not from textbooks, but from months spent living in the outback. Learning to think like prey, learning to think like predator. The Aboriginal influence on Australian SAS methodology cannot be overstated. Indigenous Australians had spent 40,000 years developing hunting techniques adapted to some of the most challenging terrain on Earth.

They understood patience on a level that Western military thinking could barely comprehend. They understood how to move through landscape without disturbing it. They understood the psychology of prey, how to anticipate movements, how to manipulate behavior, how to channel targets toward predetermined locations. These ancient skills combined with modern military training created something unprecedented.

The Australian SAS operators who deployed to Vietnam were not simply soldiers. They were hunters in the most primal sense of the word. And they brought that hunter mentality to every operation they conducted. Consider the mindset required for the quote 10 technique that the Australians pioneered.

A standard American patrol would move through the jungle at approximately 1 kilometer per hour, making noise, leaving tracks, announcing their presence to any enemy within earshot. The Australians moved at 100 mph, sometimes slower. They would observe a section of terrain for 15 minutes before crossing it. They would choose each footfall individually, testing the ground before committing weight.

They communicated through hand signals so subtle that observers standing meters away often missed them entirely. This was not merely tactical caution. This was a fundamental transformation of human movement. The Australians trained themselves to suppress every natural instinct that might reveal their presence. They controlled their breathing.

They controlled their body odor through strict dietary protocols. They learned to sleep while maintaining partial awareness of their surroundings. They became in effect a different kind of human being. One adapted to the jungle in ways that their enemy had never imagined possible. And this transformation created a paradox that the Vietkong could never resolve.

The Vietkong had assumed they held the advantage in bush warfare because they were local, because they knew the terrain, because they had grown up in the jungle environment. What they discovered to their horror was that the Australians had mastered the environment at an even deeper level. The Vietkong were residents of the jungle.

The Australians became part of it. This brings us back to the fate of D445 and to the broader implications of what the Australians achieved. Because the story of that final radio transmission was not an isolated incident. It was one example of a pattern that repeated dozens of times throughout the Australian involvement in Vietnam.

Enemy units entering Australian controlled territory simply ceased to exist. They did not retreat. They did not surrender. They did not engage in conventional combat and suffer conventional losses. They vanished. and the psychological impact on the Vietkong was documented extensively in captured documents and intercepted communications.

Enemy commanders began issuing specific orders regarding the underscore quote unorthps after dark. Patrols that encountered signs of Australian presence, the cut boots, the arranged bodies, the mysterious ration packs, were ordered to withdraw immediately regardless of mission parameters. This was psychological warfare at its most effective.

But it came with a cost that no one wanted to discuss publicly. The methods that made the Australians so effective also raised profound ethical questions that neither American commanders nor Australian politicians wanted to address. The cut boots served no military purpose that could be justified in standard operational terms. It was purely psychological, a deliberate marking of enemy personnel designed to terrorize survivors.

The same applied to the positioning of bodies, the underscore_12 left at elimination sites, the entire theater of horror that accompanied Australian operations. These were not the actions of soldiers simply trying to win a war. These were the actions of hunters trying to break their prey psychologically before finishing them physically.

American observers who witnessed Australian methods frequently reported being disturbed by what they saw. One American sergeant attached to an Australian unit in 1968 wrote in a letter home that was later included in official records. His observations would haunt military historians for decades. He described watching Australian operators return from a patrol with what he called underscore_13, a detached, almost peaceful expression that bore no resemblance to the thousand-y stare of combat trauma.

He wrote that he had seen men who enjoyed their work before, but the Australians were different. They did not seem to enjoy the hunt. They seemed to exist only for the hunt, as though hunting was not what they did, but what they were. This characterization was unfair in many ways.

Australian SAS operators were professional soldiers operating under extreme conditions against a determined enemy. Many of them experienced profound psychological consequences from their service. Many struggled to readjust to civilian life. Many carried wounds visible and invisible for the rest of their lives. Yet, there was also truth in the American sergeant’s observation.

The Australian approach to Vietnam required operators to adopt a mindset that existed outside conventional military ethics. They were not simply asked to defeat the enemy. They were asked to become something that the enemy would fear more than conventional death. They were asked to transform themselves into predators and to hunt human beings with the same cold efficiency that their Aboriginal teachers had hunted game for millennia.

The question of whether this was justified remains contested to this day. Supporters argue that the Australian method saved Allied lives. Each Vietkong fighter eliminated through patient, methodical hunting was one less fighter available to attack Firebase Nui Dat to ambush supply convoys to plant mines along route two.

The psychological impact on enemy morale multiplied this effect. For every fighter the Australians directly eliminated, several more became combat ineffective due to fear and demoralization. Critics counter that effectiveness cannot be the sole measure of military ethics. The deliberate cultivation of terror, they argue, degrades the humanity of those who practice it as much as those who suffer it.

The cut boots and arranged bodies and whispered nightmares served no purpose except to create horror. And horror, once unleashed, does not confine itself to enemy combatants. The Australian SAS veterans themselves rarely engage in these debates. Most declined to speak publicly about their methods.

Those who have given interviews typically express neither pride nor shame but a kind of flat acceptance. They did what was necessary. Their mates came home alive. The rest is commentary for people who were not there. What remains undisputed is the impact of their operations. And that impact extended far beyond the jungles of Vietnam.

The province of Fuaktui, which the Australians were assigned to control, became the safest region in South Vietnam for Allied personnel. While American forces in other provinces suffered constant casualties from ambushes and booby traps, Australians moved through their territory with near impunity. The Vietkong effectively seated the area, preferring to operate in regions where they faced only American firepower rather than Australian hunting techniques.

This success created a strange paradox that would shape military history. The very effectiveness of Australian methods meant they remained largely invisible to the American public and military establishment. There were no dramatic battles to report, no casualty figures that demanded explanation, no visual spectacle for evening news broadcasts.

The Australians simply conducted their quiet, methodical, terrifying work, while American attention focused on more conventional operations elsewhere. When the war ended, this invisibility extended to the historical record. American accounts of Vietnam dominated public memory. The Australian contribution was reduced to a footnote, acknowledged politely, but rarely examined in depth.

The lessons the Australians had learned and could have taught were filed away and forgotten. But those lessons were not lost entirely, and their influence would reshape modern warfare. In the decades following Vietnam, elements of Australian methodology began appearing in special operations doctrine worldwide.

The emphasis on psychological warfare, the integration of indigenous tracking techniques, the patient, methodical approach to eliminating enemy forces, the understanding that terror properly applied could multiply the effect of small teams beyond anything achievable through conventional force. Modern special operations units from dozens of countries now train techniques that trace their lineage directly to the Australian SAS in Vietnam.

The SEALs, the SAS of Britain, the German KSK, the Israeli Sireet Matkall, all of them have incorporated elements of what the Australians pioneered in the jungles of Fuaktoy province more than half a century ago. The radio operator who sent that final transmission. The man who spoke those seven words about the forest eating his unit alive was never identified.

His body was never recovered. His fate remains unknown to this day. But his words have echoed through military history in ways he could never have imagined. They have become a symbol of what happens when a military force fully commits to the hunter’s methodology. When soldiers transform themselves into predators. When the jungle stops being an obstacle and starts being an ally, the forest is eating us alive.

Those seven words were not a metaphor. They were a precise description of what was happening to unit D445 in the pre-dawn hours of September 14th, 1969. The forest, in the form of 12 Australian operators who had made themselves part of it, was literally consuming the enemy one fighter at a time. It was hunting them with patience and skill and terrifying efficiency.

The Australians who conducted that operation returned to Firebase Nui dot without fanfare. They cleaned their weapons. They wrote brief clinical afteraction reports. They ate hot food for the first time in 3 weeks. And then they began preparing for the next patrol. Because the jungle was vast and there were more units to hunt.

The story of D445 is not unique. It is merely one documented example among dozens, perhaps hundreds. Many operations from that era remain classified. Many will never be declassified. The full scope of what the Australian SAS achieved in Vietnam, and the methods they used to achieve it may never be known outside the tight-knit community of those who served, but the legend they created endures.

In the villages of Fuaktoy province, elderly residents still speak of the time when the jungle itself turned against the gorillas. when men went into the trees and simply never returned. When the night became something to fear more than any bomb or bullet. And in militarymies around the world, instructors still teach the lesson that the Australians demonstrated so thoroughly.

Numbers do not win wars. Firepower does not win wars. Technology does not win wars. What wins wars is the willingness to become something that your enemy cannot comprehend. to operate outside their framework of understanding to become in their minds something that is not quite human anymore. The forest is eating us alive.

Those seven words summarized an entire philosophy of warfare. They captured the essence of what happens when highly trained operators fully embrace the methodology of the hunt. They expressed the primal terror that humans experience when they discover they are no longer the apex predator. The Australian SAS wrote those words into history without ever speaking them.

They wrote them in cut boots and silent movements and patient methodical elimination of everything that stood against them. They wrote them in the nightmares of surviving Vietkong and the reluctant admiration of American observers. They wrote them in classified files that would not be opened for decades.

And in the humid darkness of the Vietnamese jungle, on nights when the monsoon rains drowned all other sound, they continued their work, patient, methodical, relentless. The forest made flesh. The ghost stories that American veterans brought home from Vietnam often mentioned the Australians. Quiet men who did not drink much and said even less.

Soldiers who would disappear into the jungle for weeks at a time and return looking as though they had never left the firebase. warriors who seem to exist in a different reality than everyone else. These were not exaggerations. These were descriptions of what happens when military training reaches its ultimate expression.

When the boundary between human and environment dissolves, when the hunter becomes so skilled that prey cannot even perceive the threat until it is far too late. The Vietkong called them maung, jungle ghosts. But the name was inadequate. Ghosts are supernatural. Ghosts operate outside the rules of physics and biology. What the Australian SAS achieved was entirely natural.

It was the product of training and discipline and methodology refined over years. It was the predictable outcome when serious professionals dedicated themselves completely to mastering a particular form of warfare. There were no ghosts in the jungles of Fuaktoui Province. There were only men who had learned to move like ghosts, to think like ghosts, to strike like ghosts and vanish like ghosts.

Men who had studied the ancient hunting techniques of a people who had mastered this craft over 40,000 years. Men who had combined that ancestral knowledge with modern military science to create something that the world had never seen before. The seven words of that final transmission stand as a testament to their success. The forest is eating us alive.

Not attacking, not fighting, eating. The word choice was precise, almost poetic. It captured the slow, inevitable, utterly terrifying nature of what was happening. Not a battle, but a consumption. Not a firefight, but a feeding. And somewhere in the darkness of that long ago night, 12 Australian operators continued their work, silent, patient, hungry.

The forest was indeed eating the men of D445, and the forest would not stop until every last one of them had been consumed. This is the story that official histories do not tell. This is the chapter of the Vietnam War that militarymies study, but public memory ignores. This is what happens when a small nation facing challenges beyond its conventional means, develops capabilities that transcend conventional understanding.

The Australian SAS in Vietnam did not win the war. No one won the war. But in their small corner of that vast and tragic conflict, they achieved something that larger forces with greater resources could not match. They made the enemy afraid, not of dying. The Vietkong had long since accepted death as the price of their struggle.

They made the enemy afraid of something worse than dying. They made the enemy afraid of the jungle itself. And that fear once planted never fully disappeared. Decades later, Vietnamese veterans of the conflict still spoke of the Maung with a respect that bordered on awe. Not hatred, not anger. Awe. The recognition of having faced something that operated on a level they could not match.

Something that had turned their greatest advantage, their mastery of the jungle environment against them with devastating effect. The final transmission of unit D445 echoes through time. Not because it was unique, but because it was recorded. Because American intelligence happened to be monitoring that frequency at that moment.

Because someone thought to preserve those words for posterity. How many other units experienced the same fate without leaving any record? How many other radio operators tried to warn their comrades of the forest eating them alive only to find their transmissions unmonitored, their words lost to history? We will never know. The full scope of Australian SAS operations in Vietnam remains partially classified more than 50 years after the conflict ended.

The complete records may never be released. The men who could explain what really happened are aging, taking their secrets with them. But the legend endures in the training programs of special forces worldwide. In the nightmares of those who face them in the seven words spoken by a terrified radio operator on a monsoon night more than half a century ago.

The forest is eating us alive. It was not metaphor. It was not exaggeration. It was the simple truth of what the Australian SAS had become. And it remains a warning to anyone who would underestimate what a small force of dedicated professionals can achieve when they fully commit to mastering their craft. The jungles of Fuaktui province have long since regrown.

The fire bases are ruins. The war is history. But somewhere in those trees, the ghosts still walk. Not supernatural ghosts. Human ghosts. The memory of what 12 men could do when they made themselves part of the forest. When they hunted with patience and skill and utter implacable determination. The forest is eating us alive.

Seven words. A complete philosophy of warfare. A testimony to human capability at its most focused and most terrifying. A memorial to those who vanished and those who made them vanish. The story of the Australian SAS in Vietnam is not comfortable. It is not heroic in the conventional sense. It does not offer easy lessons or simple morals.

But it is true and its truth demands to be remembered. Even when that truth challenges our assumptions about what war is and what warriors can become. In the end, the forest did not eat unit D445. 12 Australian operators did. They simply made the forest their weapon, their camouflage, their ally. And in doing so, they demonstrated what happens when the distinction between hunter and environment completely dissolves.

The Vietkong never found a counter to the Maang. They simply avoided them whenever possible and prayed when avoidance was not possible. The prayers rarely helped. And in the quiet archives of military history, the recordings of that final night still exist, classified, preserved, waiting for the day when the full story can finally be told.

The forest is eating us alive. Those words were true then. They remain true now and they will remain true as long as there are warriors willing to transform themselves completely in pursuit of their mission. The Australian SAS showed what was possible. The world is still learning from their example. This is their story. This is their legacy.

This is the truth that official history preferred to forget. The forest was hungry, and the Australians made sure it was fed.