In the spring of 1967, somewhere in Puaktu province, a Vietkong regional commander sat under the canvas awning of a concealed bunker. Rain drums steadily on the rubber trees above. The sound was constant, rhythmic, the kind of rain that comes in from the South China Sea and settles over the coastal provinces for days at a time.

Before him lay a stack of intelligence reports, handwritten on thin rice paper, brought in by runners over the past fortnight. Each report had traveled through multiple hands, passed along the network of trails and tunnels that connected VC units across the province. Some of the paper was stained with mud. Some bore the creases of having been folded and hidden quickly when helicopters passed overhead.

He read one line slowly, then laughed. small foreign patrols operating in the forest. The term written in Vietnamese was more specific than that. His scouts had used the phrase those who walk without weight. A poetic way of saying these troops left no impression, no mark, no consequence. It was not a compliment.

In the language of jungle warfare, where presence and control of territory meant everything. Walking without weight meant you didn’t matter. He turned to his political officer, a thin man in his 40s who had been with the movement since the French days, and shook his head. They shared a knowing look. The Americans, they understood. Loud, aggressive, overwhelming in their use of firepower.

Dangerous in their own way, yes, but predictable. You heard them coming from kilome away. Their helicopters announced their presence. Their artillery preparations told you where they plan to strike. But these Australians, a token force. Four men here, six men there, wandering through the jungle on what appeared to be aimless patrols.

What could they possibly accomplish in a war measured in battalions, in divisions, in core level operations? The commander took a pen and wrote a brief notation in the margin of the report. continue monitoring but assigned no special priority. He filed the paper away with the others and moved on to more pressing concerns.

There was an upcoming operation against an ARVN outpost to plan rice supplies to redistribute a disciplinary matter involving two fighters who’d been caught stealing from a village. The Australians barely registered as a footnote in his daily concerns. But within a year, his battalion stopped laughing. Within a year, every VC commander in Puak 2A province would be writing different kinds of reports about the Australians.

Reports that emphasized caution, respect, and adaptation. They learned that the SAS were already watching them for days at a time, recording every movement, every mistake, every pattern. They learned that the Australians moved differently. Not like any force they had encountered before. Not like the French who’d been predictable in their colonial arrogance.

Not like the Americans who announced themselves with mechanical thunder. The Australians moved like the jungle itself. And they learned it the hard way. through ambushes that materialized from empty ground. Through artillery strikes that found them in supposedly secure areas, through the constant gnawing awareness that they might be under observation at any moment and never know it.

This is the story of how respect replaced mockery. How a handful of quiet professionals changed the way an entire enemy command structure thought about the jungle. How the hunters became the hunted. and how they only realized it when it was too late and how the Vietkong discovered that the most dangerous patrols aren’t always the loudest ones.

To understand why the Vietkong underestimated the Australians, you have to understand the tactical picture they were working with in 1966 and early 1967. The Australian task force at Nui dot was small by any measure. Roughly 4,500 men at its peak, responsible for Fuak toe province, a slice of jungle, rubber plantations, and coastal villages about 70 km southeast of Saigon.

The entire province covered approximately 2,500 km. dense terrain, multiple population centers, extensive tunnel networks built over decades of resistance warfare. To put that in perspective, American operations in the Central Highlands or up near the DMZ, involved entire divisions, 20,000 men or more. The Australian presence, by comparison, barely registered on the strategic map.

From the VC perspective, this made perfect sense. Australia was a junior partner in the American war effort. A political token to show international support. The real threat, the existential danger to VC operations came from American firepower. They had learned to respect that firepower through hard experience.

B-52 strikes that turned entire grid squares into moonscapes. artillery fire support bases that could bring down hundreds of rounds in minutes. Helicopter gunships that could appear without warning and tear through jungle canopy with mini gunfire. The VC had adapted their entire tactical doctrine around that reality.

Avoid large American formations. Never concentrate in numbers that justified air strikes. Strike when isolated. Hit and fade. melt back into the villages, into the tunnels, into the civilian population where American firepower couldn’t follow without creating political problems. This doctrine had worked not perfectly, but well enough to sustain the insurgency.

The VC controlled significant portions of the countryside. They collected taxes. They recruited. They moved supplies along established networks. And they did it all while surviving the most powerful military in the world. Then the Australians arrived at New Dat. The VC watched them established their base. Watched them begin patrolling and what they saw confirmed their initial assessment. Not a serious threat.

Australian reconnaissance patrols were tiny. Four to six men, sometimes fewer. They carried limited ammunition, 120 rounds per man, compared to the 300 plus that American infantry typically hauled. They didn’t call in air strikes every time they saw movement. They didn’t request artillery support at the first sign of enemy presence.

They just walked quietly through areas the VC considered their own backyard. The long high hills where VC units had operated freely for years. The May Tao ranges riddled with trails and cash sites. The swampy lowlands near the rung sat where helicopter operations were nearly impossible. and VC scouts, experienced men who’d survived French patrols, ARVN sweeps, and American search and destroy operations, reported that they couldn’t detect these Australian movements.

In any other context, this would have been alarming. If your scouts can’t find the enemy, that means the enemy is very, very good. It means they’re operating at a level of fieldcraft that exceeds your ability to detect them. But the VC commanders didn’t interpret it that way. Instead, they assumed incompetence.

If the scouts couldn’t find the Australians, it was because the Australians weren’t doing anything worth finding. They were wandering around aimlessly, gathering intelligence that was probably useless and generally making themselves feel useful without actually affecting the war. There was another factor at play. Pride.

The kind of pride that comes from surviving in the harshest possible conditions for over a decade. The Vietkong and the North Vietnamese regulars who increasingly reinforce them had been fighting in these jungles since the early 1950s. They knew the trails like the back of their hands. They understood the seasonal flooding patterns when rivers became impassible.

When the ground turned to mud that swallowed you to the knees, they knew how sound carried at dawn, how the wind patterns shifted in the late afternoon, where the good ambush sights were. This knowledge had been paid for in blood. French patrols had killed thousands of them. American operations had killed thousands more.

But the survivors carried lessons learned from those losses. They’d become experts in jungle warfare through brutal natural selection. So when reports came in about light walkers, about small patrols that seem to appear and disappear without purpose, the VC filed them away as background noise. Another minor inconvenience in a war full of inconveniences.

Certainly not a priority. Certainly not something that required changing established procedures. One VC company commander in a report that would later be captured and translated wrote dismissively, “The Australian patrols are like children playing in the forest. They make no noise because they do nothing.

Our fighters pass them without concern.” That line, “Like children playing in the forest,” captured the prevailing attitude perfectly. That assumption cost them dearly because what the VC didn’t understand yet was that silence in the jungle isn’t a sign of incompetence. It’s a sign of mastery. Let’s meet the men who would change. That assumption forever.

In late March 1967, a fourman SAS patrol prepared to step off from their forward operating base near Newi Dot. The temperature was already climbing toward 35° C, and it wasn’t even 9 in the morning. Humidity hung in the air like a physical presence, the kind that made your uniform stick to your skin and turn simple movement into an exercise and sweat management.

The patrol commander was a corporal, young, barely 24, but already on his second tour. His first tour had been in Borneo during confrontation, tracking Indonesian infiltrators through primary jungle. That experience showed in the way he moved, in the decisions he made without apparent thought, in the quiet confidence that came from having done this before and survived.

That was typical for the SAS. Junior NCOs led patrols because the regiment believed fundamentally in pushing responsibility down to the lowest level. If you could think for yourself, if you could keep your head when things went wrong, if you could make decisions under pressure without waiting for someone to tell you what to do, then you got the job.

Rank was less important than competence. The other three members of the patrol each brought their own skills to the table. The lance corporal was the scout. He’d grown up in the Queensland bush, the son of a timber cutter, and he’d learned to track wabes before he could read. In the SAS, those skills translated directly to reading human movement patterns in jungle terrain.

He could spot a three-day old bootprint in leaf litter. He could tell you which direction a patrol had been moving by the way vines were bent. He was 22 years old and looked about 17. The signaler was older, 27, a career soldier who joined regular army before transferring to SAS. He carried the AN PRC25 radio, 11 kg of electronics.

That was his responsibility to keep functional in an environment that destroyed electronics. Moisture, heat, constant, jarring movement, mud that got into every crevice. The radio was their lifeline to fire support, to extraction, to civilization. If it failed, they were on their own. He treated it with the kind of care most men reserve for newborn children.

The fourth man, another lance corporal, was the patrol’s medic. He’d done the standard army medical training and then the specialized SAS course that taught you how to handle trauma medicine with limited supplies and field conditions, sucking chest wounds, arterial bleeds, the kind of injuries that killed you in minutes if they weren’t treated immediately.

He carried extra morphine, extra bandages, and the quiet knowledge that if someone got hit badly, he’d be the one who determined whether they lived or died. None of them fit the Hollywood image of special forces. No bulging muscles, no thousand-y stairs. They were lean, economical in their movements, and looked like they could have been farm workers or shop assistants in civilian life.

But watch them prepare for a patrol and you’d see the difference immediately. Their preparation was methodical ritual almost. Each step performed in the same order with the same attention to detail every single time. First boots. The corporal checked every eyelet, every stitch, every potential point of failure.

He’d broken these boots in over two months, wearing them on every training patrol until they molded to his feet like a second skin. Wet boots bred blisters. Blisters bred infection. Infection bred evacuation. In a four-man patrol operating 40 km from base, losing one man to something as stupid as foot rot meant losing 25% of your combat power. Unacceptable.

Second gear. Everything that could rattle, click, or make any noise whatsoever was taped, padded, or removed. Weapon slings were wrapped in cloth torn from old T-shirts. Dog tags were wrapped in rubber bands cut from inner tubes. Even the metal clips on their webbing were checked, rechecked, and often replaced with paracord ties that made no sound.

They had learned this the hard way. In Borneo, a patrol member’s water bottle clip had squeaked during a river crossing. The Indonesian patrol they were tracking heard it. The resulting firefight killed two men and compromised the mission. After that, noise discipline became religious. Third, water discipline. They’d carry enough for 3 days, calculated precisely based on their planned route, expected exertion level, and the humidity.

But no more. Every liter of water weighed a kilogram. Every kilogram you carried was a kilogram you’d haul through chestde swamp up 45° ridge lines, through wait a while vine that tore at your skin like barbed wire. The Americans thought they were crazy. American infantry typically carried four to six lers per man per day.

The SAS carried less than half that and made it last through water discipline, drinking only when necessary, never to comfort, and planning movement to intersect with streams wherever possible. Fourth, weapons. Each man carried an L1A1 SLR, the self-loading rifle that was standard issue for Australian infantry. Semi-automatic 7.

6 62 miming me restoring 20 round magazine. Effective range out to 600 m. Reliable, powerful, but heavy. Over 4 kg unloaded. They’d zeroed their weapons at the range 2 days ago. Now they performed final function checks. Magazine insertion, bolt cycling, safety function, trigger pull. Each man knew his weapon intimately. Could strip and reassemble it blindfolded.

could clear a stoppage in the dark by touch alone. Fifth, final equipment check. They laid out everything they’d carry and went through item by item. Ammunition, 820 rounds per man split between six magazines, one in the weapon, five in pouches, grenades, two fragmentation, one smoke, one white phosphorus for emergency signaling rations.

Enough for 6 days. The meals dehydrated and repackaged to save weight. Medical supplies, field dressings, morphine, antibiotics, water purification tablets, navigation, map, compass, protractor, and the invaluable knowledge of how to use them even when you were exhausted, stressed, and being shot at.

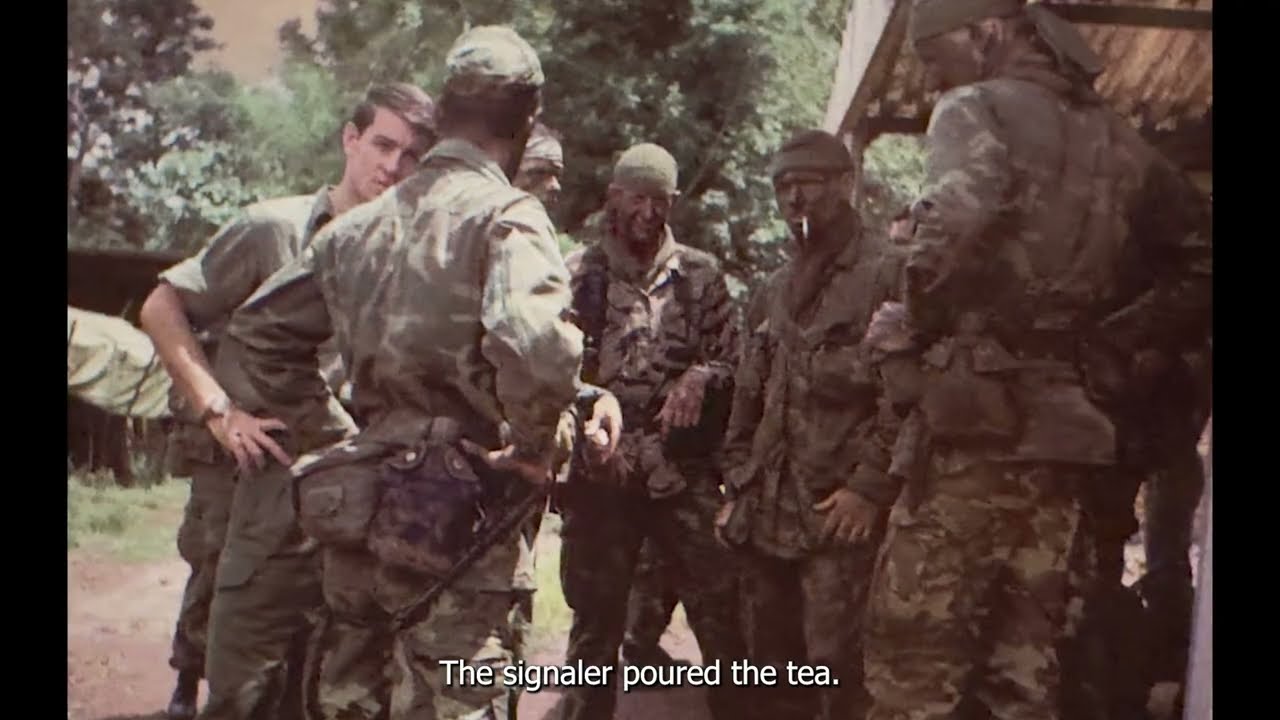

camouflage tube of camo paint, insect repellent used sparingly because the smell could give you away, and strips of hessen they’d used to break up their outlines. There was a moment just before they left where the signaler brewed a quiet cup of tea on a hexamine stove. The small blue flame hissed softly as it boiled water in a blackened metal cup.

The others sat in silence, checking maps one last time, running through the patrol’s objectives in their heads. Each man mentally rehearsing the first 24 hours. No speeches, no pep talks, no officers giving inspirational addresses about duty or courage. Just four blo to walk into the bush and do a job. The signaler poured the tea.

Strong, dark, barely any sugar because they didn’t carry much. They passed the cup around, each man taking a sip. It was a small ritual, but it mattered. The last taste of something hot before days of cold rations and muddy water. For older Australian veterans watching this, that moment carries weight. The quiet brew before patrol.

The last cigarette shared among mates. The calm before you stepped off into a place where every decision mattered and small mistakes could get you killed. They stubbed out their cigarettes, collected the butts, never leave sign, and shouldered their packs. The corporal checked his compass, confirmed the bearing one more time, and nodded to the others.

They moved toward the wire perimeter of the base, showed their IDs to the centuries, and stepped through the gate. Behind them was safety, hot food, mail from home, the company of other soldiers. Ahead was 40 km of enemy controlled jungle, VC patrols, possible ambush sites, and a mission that required them to operate in complete silence for 6 days.

Their mission was simple on paper. Reconnaissance patrol, six days. Operating box covering approximately 12 square kilometers in the northern May Tao foothills. Observe enemy movement patterns. Identify trails, cash sites, or signs of recent occupation. Report everything. Avoid contact unless compromised. Simple on paper.

Extraordinarily difficult in execution. What they didn’t know yet couldn’t know was that they were about to walk into the operational area of a Vietkong provincial battalion. A unit that had been moving supplies, preparing ambush sites, and operating with near impunity for months. A unit whose commanders still believed that the Australians were no threat at all.

That belief was about to be tested in ways the VC couldn’t imagine. 40 kilometers north of Newi dot, while the SAS patrol was checking their equipment and brewing their last tea, a Vietkong mainforce company was on the move. They had left their secure area before dawn, moving in the pre-light darkness when visibility was minimal, but just enough to navigate by.

This was standard procedure. Move during the hours when enemy helicopters were grounded. when Australian patrols were likely to be static in night harbor positions when the risk of compromise was lowest. 60 fighters, give or take a few, who were out sick or on detached duty.

A mix of local recruits, some as young as 16, and northern regulars who’d come down the Ho Chi Min Trail over the past year. The regulars were easy to spot even in uniform. They moved differently with the confidence of men who’d survived multiple battles. They carried better weapons, usually AK-47s instead of the older SKS rifles. And they had a hardness around their eyes that came from months of walking south through Laos, being bombed by B-52s, watching friends die from disease and American air strikes.

The company commander was one of these northerners, Nguian Van Duk, though his fighters only knew him by his nom dear. He was 34 years old, had been fighting since he was 19, and carried a Chinese-made AK with a folding stock that he’d taken off a dead ARVN Ranger 3 years ago. He’d studied the reports about Australian patrols, read them, considered them, and largely dismissed them as exaggerated.

His scouts were good, better than good. They were survivors of a decade of warfare. If they couldn’t detect these Australian patrols, it meant the Australians weren’t worth detecting. His objective today was straightforward. Move from their secure village complex near the Courtney Rubber Plantation to a new cash site in the eastern Mattow hills.

The cash would hold rice purchased sometimes forcibly from local farmers, medical supplies smuggled in from Cambodia, ammunition brought down from the north, and propaganda materials for distribution in contested villages. Once established, this cash would support future operations deeper into the province. Ambushes on Highway 15, attacks on ARVN outposts, tax collection operations in villages that had been leaning toward the government side.

The company moved in a loose column formation, fighters spaced about 5 m apart. This was doctrine, close enough to maintain visual contact, far enough apart that a single burst of automatic fire wouldn’t take out multiple men. They weren’t sloppy. Duke wouldn’t have tolerated sloppiness. These were experienced troops who’d survived by being careful.

But they moved with confidence. This was their ground. They had walked these trails dozens of times. They knew where the muddy sections were, where you had to detour around flooded streams, where the good rest spots were located. At the head of the column, a female scout moved with careful precision. Her name was Lawn.

She was 19 years old and she’d been with the unit for two years. She joined after ARVN soldiers burned her village during a search operation. Whether her village had been harboring VC or not was almost irrelevant by that point. Once your home was ashes, the choice of sides became simple. Her job as scout was critical.

She walked 50 m ahead of the main column, reading the jungle, looking for signs of recent passage, checking for ambush positions, watching for the subtle indicators that meant danger, a pile of disturbed earth that might hide a mine, fresh machete cuts on vegetation that indicated recent trail clearing, bootprints that were too regular, too deep, suggesting foreign soldiers rather than local fighters who wore sandals.

She was good at her job. She’d spotted two ARVN ambushes in the past 6 months, saving the company from walking into prepared kill zones. Duke trusted her completely. Behind her, the column moved with practiced efficiency. Some fighters carried rice bags, 10 kg each, strapped to their backs. Others carried ammunition boxes, the weight distributed with bamboo poles across two men’s shoulders.

Several had RPG7 launchers, the distinctive tubes slung across their backs with rockets carried separately to avoid accidental detonation. Every so often, Lon would stop. She’d raise her hand, and the entire column would freeze. Everyone would listen, scanning their arcs, weapons ready. Then she’d signal the allcle, and they’d continue.

This was routine. They’d done it hundreds of times. What they didn’t know, what they had no way of knowing was that Australian SAS had been operating in this area for 3 weeks. Small patrols moving on overlapping arcs, building a detailed picture of enemy movement patterns. The SAS had noted the increase in foot traffic through this particular area.

They had marked the new trails being cut through the undergrowth, trails that deviated from older established routes. They had recorded the times of day when movement peaked, usually dawn and dusk, when visibility was poor but still adequate for navigation. And on this particular morning, as Duke’s company moved northeast toward their cash site, an SAS patrol was settling into an observation position less than 800 m away.

Pure chance, perhaps. Or perhaps it was the inevitable result of two professional military units operating in the same confined terrain. Eventually, their paths would cross. The SAS patrol had been in position since the previous evening. They’d found a good spot on a ridge line that offered visibility over three separate trail networks.

It was the kind of ground that experienced soldiers instinctively recognize as valuable. High enough to see, but not so high that you’re silhouetted. Good natural cover from vegetation. Multiple escape routes down the back slope if things went wrong. They’d spent the night there, rotating guard shifts, sleeping in 2-hour blocks, never fully resting, but managing to grab enough sleep to remain functional.

Now, as the sun climbed and the morning mist burned off, they were watching the trails below and the VC company was moving directly toward them. The SAS scout saw it first. His name was Collins, and he’d been staring at the same patch of jungle for 20 minutes, letting his eyes go slightly out of focus, watching for movement rather than n objects.

It’s a technique that takes practice. Your brain wants to focus on individual trees, individual leaves. But in the jungle, threats don’t present themselves as discrete objects. They present as movement, as patterns that don’t quite fit. And there it was, a broken twig at chest height, snapped cleanly rather than torn. Fresh.

The break was still white. Hadn’t oxidized yet. Maybe an hour old, maybe less. Collins froze midstep, one boot still hovering above the jungle floor. He was in the middle of shifting position, moving from his observation point back to the main patrol location to rotate with another man. But something about that twig made him stop completely behind him.

The patrol commander, Corporal Davis, saw the freeze and immediately signaled the others. Everyone stopped. No hand signals beyond that initial gesture. No need. In the SAS, a freeze meant something was wrong, and everyone responded instantly. The freeze was a trained response drilled into them during selection and reinforced through countless training patrols.

When one man freezes, everyone freezes. No questions, no movement. You become part of the landscape, and you wait for information. Collins lowered himself slowly into a crouch, moving like he was underwater, every motion deliberate and controlled. He examined the area around the twig without touching anything. There in the soft earth beside a mahogany root, faint sandal prints, the kind of cheap rubber sandals that VC fighters made from old tire treads.

The edges of the prints were still sharp, clearly defined. They hadn’t been rained on yet, and there had been a brief shower around Moo 300 hours. That meant these prints were less than 4 hours old. He looked up at the canopy, checking the light angle and the moisture on the leaves. Then he moved his eyes slowly across the understory, scanning for additional sign, another indicator, a vine that had been pushed aside, bent at an unnatural angle, and hadn’t yet sprung back into its original position.

Vines in the jungle have memory. They returned to their natural state slowly. This one was still displaced, which meant whatever pushed it had passed within the last few hours. And there was more. A faint disturbance in the leaf litter, a pattern that suggested multiple feet walking in single file. And on a lowhanging branch, barely visible, a fiber from someone’s uniform had caught on a thorn.

Collins turned his head slowly. No sudden movements that might catch the peripheral vision of anyone watching. Anne made eye contact with Davis. He pointed northeast with two fingers, then held up his palm flat and tilted it in a walking motion. Contact moving this direction. Recent. Davis nodded once, then signaled the patrol into what they called close harbor.

It was a defensive formation where each man selected a position with interlocking fields of fire, creating a small perimeter that could defend against contact from any direction. This is where American and Australian doctrine diverged sharply, representing fundamentally different philosophies about the role of small unit reconnaissance.

American doctrine, particularly for units like the Rangers or LRRP teams, emphasized what they called reconnaissance by fire. If you encountered signs of enemy presence, you’d often prep the area with grenades or automatic fire, then assault through to determine what you’d found. The logic was sound.

Better to initiate contact on your terms than to be ambushed. The Australians did something completely different. They became invisible. Davis hand signaled the defensive positions with minimal movement, just fingerpointing and eye contact. Each man already knew the drill. They had practiced this hundreds of times. Select a position with good cover, good visibility of your ark, and a clear withdrawal route behind you.

Then they went static, utterly, completely still. Minutes passed, then 10 minutes, then 20. The younger members of the patrol, and at 22, Collins was one of them, fought the urge to shift position. Your leg cramped, sweat ran into your eyes. An insect landed on your neck, and you wanted desperately to swat it away.

But discipline held because movement meant detection. Detection meant compromise. Compromise meant contact. and contact for a four-man patrol operating 40 kilometers from base in the middle of enemy controlled territory was the absolute last resort. The SAS philosophy was simple. Your job isn’t to fight. Your job is to gather intelligence and get it back to headquarters where it can be used.

A four-man patrol that gets in a firefight with a company-sized enemy unit has failed its mission, even if they survive the contact. So they waited. The signaler, Thompson, had lowered himself behind a fallen log covered in moss and fungi. From 5 m away, he was invisible. He’d positioned himself so he could see Davis, but also watch his own arc to the rear.

The radio was beside him, antenna retracted, ready but silent. The lance corporal, Williams, the medic, had found a position between two tree roots that created a natural fighting position. He’d cleared away some leaves to give himself a clear field of fire, but done it so carefully that from even 2 m away, the position looked undisturbed.

They could hear the jungle around them now. Bird calls, the rustle of small animals in the canopy, the distant sound of insects. These were good signs. It meant the local wildlife wasn’t alarmed, wasn’t being disturbed by movement. Then, very faintly, they heard something else. Voices. Human voices. Speaking Vietnamese, still distant, but carrying through the still morning air.

Davis felt his heart rate pick up slightly, felt the familiar surge of adrenaline, and consciously controlled it. Slow your breathing. Relax your shoulders. Stay loose. Tension made you clumsy and clumsy got you killed. His mind ran through the calculation automatically. The kind of instant tactical math that becomes it second nature after months of training and operational experience.

Distance probably 400 m, maybe less. Sound carried strangely in the jungle, bounced off trees, got muffled by vegetation. Hard to be precise. direction northeast matching the sign Collins had found. Speed of approach, walking pace, not running. That meant they weren’t alarmed, weren’t conducting a sweep, routine movement, time to danger, close, maybe 20 minutes if they maintained current direction and speed.

Options for withdrawal back down the reverse slope of the ridge line, then east toward the planned extraction point. But that meant abandoning observation of whatever was coming or stay static and let them pass. Davis made the decision. They’d stay. Four men properly concealed could watch an enemy unit pass within meters and never be detected.

It had been done before. It would be done again. But it required absolute discipline. The voices grew louder. Now they could hear other sounds. equipment rattling despite attempts to stay quiet, the soft scuff of sandals on dirt, the occasional cough. And then Lawn appeared through the vegetation. She moved like water through the jungle.

That’s the only way to describe it. Smooth, flowing, absolutely efficient. There was no wasted movement, no hesitation. She read the ground three steps ahead, chose her path with unconscious precision, and moved with the confidence of someone who’ done this a thousand times. Her AK-47 was slung diagonally across her chest, muzzle down, one hand resting lightly on the pistol grip.

Her eyes moved constantly, scanning the trail ahead, then the vegetation to either side, then back to the trail. professional, experienced Collins watched her through the vegetation between them. She was maybe 30 m away now, moving at an angle that would bring her past their position at about 25 m.

Close, but not dangerously close if they remained still. He could see details now. The pattern on the scarf she wore knotted around her neck. The way she favored her left leg slightly, just barely noticeable, probably an old injury. the small pouch on her belt that likely held rice balls or dried fish for the day’s ration. She stopped, turned her head, listened.

Every man in the SAS patrol stopped breathing. It wasn’t a conscious decision. It was training overriding instinct. When the enemy stops, you stop everything, even your breathing. Lon’s eyes swept across the jungle, moving right to left, taking in the slope above the trail where the SAS patrol was positioned.

She was looking directly at the spot where Williams was concealed behind the tree roots. But she saw nothing because Williams had been trained to break up his outline, to use shadow and depth to his advantage, to become part of the terrain itself through careful selection of position and perfect stillness. In the SAS, they called it going to ground.

It wasn’t just about hiding. It was about becoming invisible in plain sight, which is a completely different skill. Hiding means putting something between you and the observer. A rock, a tree, a depression in the ground. Invisibility means understanding how the human eye works, what it’s drawn to, what it dismisses as background noise.

It means knowing that the eye detects movement first, contrast second, and shape third. It means using vegetation not as cover, but as camouflage, letting it break up your human outline into something that reads as natural. It’s a skill that takes months to develop and years to master. And it only works if you have the discipline to remain absolutely motionless, even when every fiber of your being wants to adjust your position or swat away the ant that’s crawling across your face.

After what felt like an hour, but was probably 15 seconds, Lan moved on. Behind her, the main column began to appear. Two by two, spaced 5 m apart. Weapons at the ready. 60 fighters give or take. a complete main force company. Davis counted silently, making mental notes. Uniforms, mix of black pajamas and khaki. Weapons, mostly AKs, some SKS.

At least three RPG launchers visible. Equipment, rice bags, ammunition boxes, what looked like medical supplies. This wasn’t a patrol. This was a logistics movement. They were relocating supplies, which meant they were establishing or resupplying a cash site. That was valuable intelligence. Cash sites were high priority targets.

Find the cash, destroy it, and you disrupted enemy operations for weeks. But right now, the priority was remaining undetected. One VC fighter stopped to adjust his pack less than 15 m from where Thompson lay behind the mosscovered log. The fighter was young, couldn’t have been more than 17. He wore an old khaki shirt that was too big for him and sandals that looked like they were falling apart.

He muttered something to the fighter behind him. Something about the weight of the rice bags they were carrying and how his shoulders were killing him. Thompson could have reached out and touched him, but he didn’t move. Didn’t even twitch. His finger rested lightly outside the trigger guard of his SLR. Never on the trigger unless you’re about to fire.

That’s basic weapon safety. And his breathing remained slow and controlled through his nose. Leeches had found their way onto his neck during the night. He could feel them there, swollen with his blood. Disgusting, but not dangerous. They could wait. The war could not. The young VC fighter adjusted his pack, took a long drink from his canteen.

metal Chinese-made with a red star embossed on it and moved on. The column kept passing. 50 fighters, 60. Some carried RPGs, the launcher tubes distinctive even from a distance. Others had satchel charges slung across their backs, canvas bags filled with explosives for demolition work. A few carried what looked like medical supplies, marked boxes that probably held bandages, antibiotics, antimmalarial drugs.

This was clearly a welle equipped oo unit, not local gorillas scraping by with whatever they could scavenge. This was a main force company with proper supply lines and organizational support. Commander Duke passed by about halfway through the column. Davis recognized him as the commander by his position, his age, visibly older than the others, and the way other fighters glanced at him, looking for signals, checking his reactions.

Duke carried himself with the confidence of experience. He wasn’t nervous, wasn’t scanning the jungle with the wideeyed alertness of a new recruit. He moved with economy, conserving energy, setting a sustainable pace that his fighters could maintain for hours. Professional soldier recognizing professional soldier. Davis felt a certain respect.

This wasn’t some amateur playing at guerilla warfare. This was a skilled commander leading experienced troops, which made them dangerous. Finally, after what felt like hours, but was actually about 20 minutes, the last VC fighter disappeared into the jungle. The sounds of movement faded gradually, voices growing distant, equipment noises becoming fainter, until there was only the ambient sound of the jungle itself.

The SAS remained frozen for another 20 minutes. This was discipline at its finest. Most soldiers after watching an enemy unit pass that close without detecting them would want to move immediately. Get away from that position, put distance between themselves and possible discovery. But Davis knew better.

If the VC had a rear security element, a small team following a 100 meters behind the main column to check for tracking, then moving now would walk straight into them. So they waited 20 minutes, 30. Finally, Davis signaled a slow, careful withdrawal. They moved back 200 m down the reverse slope of the ridgeel line, found a thicker patch of cover with good all-around visibility, and went static again.

Only then did Thompson pull out the radio. He extended the antenna slowly, making sure it didn’t catch on any vegetation, and keyed the handset. The message was transmitted in whisper level voice. So quiet that you’d have to be within a meter to hear it clearly, but the radio picked it up fine. Charlie 3 contact report. Grid reference.

He read off the 8 figure coordinates from the map. Enemy main force company estimated 60 personnel moving northeast carrying logistic supplies including RPG. possible cash site establishment. Request further orders. Over. The response came back quickly. Headquarters wanted them to follow and identify the cash site location.

Once identified, they had called in an air strike or artillery mission. Davis looked at his men. They’d been up since 0400. They’d been static for the past 3 hours. They were tired, stressed, and running on adrenaline. But there was no question about what they’d do. they’d follow. What the VC commander didn’t know, what he wouldn’t know for three more days was that the Australians had decided to shadow his company’s movement and that the hunters had just become the hunted.

Following a VC company through jungle terrain without being detected is one of the most difficult tactical tasks in modern warfare. It’s not like following someone through an open desert where you can maintain visual contact from hundreds of meters away. In the jungle, visibility rarely exceeds 30 m. Sometimes it’s as little as five.

You’re operating in their territory, following their trails, moving through areas they know intimately, and you’re seeing for the first time. You’re outnumbered 15 to one. If you’re detected, you’re almost certainly dead or captured. And you have to do all of this while maintaining radio contact with headquarters, updating your position regularly, and gathering the intelligence that justifies the risk you’re taking.

It’s a skill set that requires not just training, but a particular kind of temperament. You have to be comfortable with extended periods of intense stress. You have to be able to make split-second decisions about when to move and when to freeze. You have to trust your patrol members completely because one man’s mistake can kill everyone.

Davis laid out the plan in whispered sentences. The four men huddled together in their security position. Heads close enough that sound wouldn’t carry but far enough apart that they could still maintain situational awareness. We’ll maintain separation of at least 400 m, Davis said quietly.

Use the high ground to track their movement without closing distance. We avoid their trails entirely. We’ll parallel them through thick vegetation where sound is muffled. Collins nodded. He understood the logic. The VC would be watching their own trails, looking for signs of tracking, but they wouldn’t be watching the dense undergrowth 50 m to the side because no one moved through that terrain unless they had to.

Movement discipline, Davis continued. One man forward, three providing security. Advance 50 m, stop, observe, listen for 5 minutes minimum, then repeat. We’re not in a hurry. Slow and undetected. Beats fast and compromised. Thompson checked his watch. Radio schedule every six hours unless we have immediate intelligence.

Keep the transmission short. Grid reference. Enemy location and direction. Any significant finds. Nothing else. Williams the medic asked the key question. What if they detect us? Davis’s answer was simple and chilling. Break contact and run. EN individually to RV point alpha. We don’t have the firepower to fight a company.

Best case, we kill maybe 10 of them before they overrun us. Worst case is worse, so we don’t get detected. It was the kind of honest tactical assessment that defined SAS operations. No bravado, no false confidence, just cleareyed recognition of the reality they were operating in. They checked their equipment one more time, tightened any straps that might rattle, made sure magazines were securely seated, confirmed their escape and evasion routes on the B map.

Then they began to move. For the next 3 days, the SEAS patrol became something that existed between human and shadow. On the first day, they tracked Duke’s company through a series of ridgeel lines northeast of the Mautow Hills. The terrain was brutal. Steep slopes covered in wait a while vine creek crossings where the water ran chest deep and fast and vegetation so thick that sometimes they had to detour around impenetrable stands of bamboo.

The VC stopped twice during that day. Once near a stream where they refilled cantens and took a short rest. once in a clearing where they redistributed ammunition, moving some of the heavier loads from smaller fighters to larger ones. Each time the VC stopped, the SAS found observation points and watched. Collins would creep forward to a position that offered visibility, move so slowly that he covered maybe 10 m and 20 minutes, and then set up with his binoculars.

The others would establish security positions behind him, creating a small perimeter that could defend against detection from any direction. And they’d watch, not just counting numbers, though that mattered, but observing. Who seemed to be in charge? Who were the experienced fighters versus the new recruits? How well equipped were they? Did they have radio communication? What was their march discipline like? Were they sloppy or professional? All of this went into the intelligence picture.

Thompson updated headquarters every six hours, transmitting in that same whisper quiet voice. 8 figure grid references accurate to within 10 m. Enemy strength and composition. Direction of travel and estimated speed. Any significant observations. Charlie 3 position update. Grid reference 738294. Enemy continuing northeast.

Estimated speed two clicks per hour. Observed weapons include six RPG launchers, multiple automatic weapons, possible crew served weapon broken down for transport. No radio antenna observed. Over. The responses from headquarters were equally brief. Roger Charlie 3. Continue tracking. Air assets on standby. Out.

It was a strange kind of warfare. No shots fired, no direct contact, just patient professional observation, gathering the intelligence that would eventually be used to destroy this enemy unit. On the second day, the VZ made their first mistake. They lit cooking fires. It was around 1600 hours, overcast with a low cloud ceiling that promised rain by evening.

Duke had decided to let his fighters prepare a hot meal before the rain started. The logic made sense. Cooked rice was easier to digest than the dry rations they had been eating, and morale mattered. He calculated that the smoke would disperse before it became visible from the air. The cloud ceiling was low enough that helicopters would have trouble operating, and they’d be moving again in an hour.

So even if the smoke was spotted, by the time any reaction force arrived, they’d be gone. What he didn’t calculate was that there were four Australians less than 600, 8 m away, and smoke travels horizontally through jungle terrain before it rises. Davis smelled it first. Wood smoke with the distinctive scent of fish sauce, that pungent fermented smell that’s used in Vietnamese cooking.

He raised his hand, signaling a halt, and the patrol froze. They waited, oriented themselves, trying to pinpoint the source. Collins checked the wind direction, light out of the northeast. That meant the VC were northeast of their position. Davis made a decision. They’d close the distance slightly, try to get eyes on the camp.

It took them an hour to move 300 m, careful, deliberate, using every bit of cover and concealment. They were moving toward the enemy now, which meant the risk of detection increased dramatically, but the intelligence value of observing a temporary VC camp was worth it. Collins found them first. Through a gap in the vegetation, he could see a small clearing where the VC had set up for their meal.

Several small fires. Fighters gathered in groups of four or five, passing around bowls of rice. Some were cleaning weapons. Others were resting, leaning against their packs. From 200 m away, concealed behind a fallen log that provided both cover and an excellent observation point. The SAS watched for the next 45 minutes.

Davis sketched everything in his notebook. the layout of the camp. Sentry positions, only two, both watching the approaches along the trail, neither watching the thick jungle to the sides. Defensive positions, minimal, just a few cleared firing lanes. Equipment organization, supplies stacked in the center, fighters personal gear distributed around the perimeter.

This was valuable intelligence about VC field procedures, how they organized temporary camps, what their security protocols were, where the weaknesses existed, all of it documented, all of it transmitted back to headquarters that evening. On the third day, the VC reached their destination, and the SAS patrol realized they had stumbled onto something much bigger than a simple logistics movement.

The cash site was in a small valley, roughly 500 m long and 200 m wide, ringed by hills on three sides with thick jungle canopy overhead. From the air, it would have been invisible, just solid green vegetation. From the ground, it was accessible only through two narrow approaches, both of which could be easily defended or blocked.

It was, in short, an excellent tactical position. Whoever had selected this site knew exactly what they were doing. The SAS watched from a rgeline 400 m to the south as Duke’s company began work. They started by clearing vegetation, not cutting it all down, but thinning it selectively to create working space while maintaining the overhead concealment. Smart work.

No obvious clearing that would show up on aerial reconnaissance photos. Then they began digging storage pits. each about 2 meters deep and 3 meters square, lined with bamboo matting to keep the contents dry. The VC worked in shifts, some digging while others provided security or prepared food.

It was organized, efficient work. Through binoculars, Davis watched the supplies being unloaded and cataloged. rice bags, each marked with characters he couldn’t read but could estimate by size, probably 25 kg each. Medical supplies and marked boxes, ammunition crates, wooden with rope handles, and then RPG rounds, lots of them.

Davis counted carefully, at least 60 rounds visible, maybe more still packed. Each round came in a wooden carrier tube that held one round plus the booster charge. The VC were stacking them carefully in one of the storage pits, arranging them to maximize storage space. That was the moment Davis realized this wasn’t just a standard supply cache.

A VC company normally carried maybe 10 to 12 RPG rounds total for their launchers. This cash held five times that much, which meant either multiple companies would be resupplying from here, or a single unit was planning operations that required massive amounts of RPG firepower. He pulled out his map and studied the terrain, thinking through the tactical possibilities.

From this cache location, the VC could strike multiple targets within a 48hour march. The Australian fire support base at Nui dot 15 km southwest. The main highway between Ben Hoa and Vong Tao 12 km west. The ARVN district headquarters at Puak High 18 km east. More concerning the amount of supplies being cash suggested this was meant to support operations lasting weeks, maybe months.

This wasn’t preparation for a quick raid. This was establishing infrastructure for sustained combat operations. Davis thought about the intelligence briefings he’d sat through before this patrol. There had been indications that the VC were planning something big in Fuakt Thai province. Increased recruitment activity in the villages, more tax collection operations, which meant they were raising funds, more aggressive propaganda efforts.

This cache site might be the physical evidence of those preparations. He pulled Thompson close and whispered the radio report. Thompson nodded, made sure his antenna was properly concealed, and keyed the handset. Charlie 3 priority contact report. The word priority meant this was important enough to break radio silence outside the normal schedule.

Major enemy cache site being established. Grid reference 749311. Estimate battalion level resupply capability. Observed 60 plus enemy personnel. Extensive storage preparation. High volume of RPG ammunition. Medical supplies. Rice stock piles. Assessment. Preparation for sustained operations.

Request immediate tasking. Over. There was a pause on the other end. Davis imagined the duty officer at headquarters processing this information, pulling out maps, calling in the intelligent staff. The response when it came was tur. Charlie 3, roger your report. Maintain observation. Update every 2 hours. Prepare target package for air strike. Acknowledge.

Over. Charlie 3 acknowledges. Wilco out. Target package. That meant they’d need detailed information about the cache site, precise grid coordinates for each storage pit, location of any defensive positions, best approach, vectors for strike aircraft, likely escape routes the VC would use if the site was hit.

Getting that information meant one thing. They’d have to get closer. Much closer. Davis called the patrol together for a whispered conference. They were concealed behind a rocky outcrop that provided good cover 400 meters from the cache site, relatively secure for the moment. We need to set up a proper OP, Davis said quietly.

Close enough to get detailed observation, grid each storage pit, map the defensive positions, count exact numbers of personnel and weapons. Williams, the medic, raised the obvious question. How close? 150 m. Maybe closer if we can find good cover. Collins exhaled slowly. Wedged 50 m. That was danger close by any standard.

Close enough that if they were detected, they wouldn’t be able to break contact before being overrun. Close enough that they’d be able to hear conversations, see individual faces, observe details that most reconnaissance patrols never got close enough to see. When? Thompson asked. Tonight. After they’ve settled in. We’ll move during their evening meal when they’re distracted and the light is failing.

Set up before full dark. Then we sit on them for as long as it takes to get the complete picture. It was the most dangerous part of the mission yet. moving toward an enemy position at night, getting into position while 60 VC fighters were less than 200 meters away, and then remaining hidden for potentially hours or even days.

But it was also their job. This is what the SAS existed to do. Not the dramatic hostage rescues or counterterrorism operations that would make them famous decades later. this patient, professional, high-risk reconnaissance in enemy territory. Gathering the intelligence that allowed commanders to make informed decisions about where and when to strike, they checked their equipment one more time, made sure everything was silent, confirmed their individual escape routes, established rally points in case they had to split up, and then

they waited for evening. They moved at dusk. That magical dangerous period when day transitions to night. When shadows lengthen and merge. When the human eye struggles to adjust between light and dark. When even experienced centuries find it difficult to distinguish movement from the natural sway of vegetation in the evening breeze.

The patrol moved in a modified diamond formation. Collins led his scout, moving perhaps three paces, stopping, listening, moving again. Behind him, Davis at the second position, then Thompson with the radio. Finally, Williams walking backward half the time, ensuring nothing crept up from their rear.

It took them 2 hours to cover 250 m. That’s not a typo. 2 hours for 250 m. That’s just over 100 meters per hour, slower than a crawl. But speed wasn’t the objective. Undetected movement was. Collins would choose each footfall with extraordinary care. Test the ground before committing his weight. Avoid any dead branches that might crack.

Move around rather than through vegetation that might rustle. Stop every few steps to listen, to observe, to make sure they hadn’t been detected. It was exhausting work. Not physically, they weren’t moving fast enough for that. But mentally, the constant vigilance, the hyper awareness of every sound, every shift in the wind, every change in bird calls or insect noise that might indicate enemy presence.

They crossed one trail during that movement, a well-used path, dirt packed hard by regular foot traffic. This was dangerous. Crossing a trail meant exposing yourself, even briefly, to any enemy patrol that might be using it. Collins stopped at the trail edge and watched for 20 minutes. Just watched, looking for any sign of recent passage.

Any indication that a patrol might be moving along it? Nothing. He signaled Davis, who moved up. They made eye contact. No words necessary. Collins would cross first, fast but silent. Then he’d cover while the others crossed one at a time. Collins took three quick steps across the trail, maybe 2 m wide, and melted into the vegetation on the far side.

He went prone immediately, weapon up, covering back toward the trail. Davis followed, then moving carefully because the radio antenna added height and could easily catch on overhanging vegetation. Finally, Williams walking backward for the first two steps to maintain rear security, then spinning and crossing. They waited another 20 minutes on the far side, listening, making sure the crossing hadn’t been observed.

Then they continued the slow movement toward the cash site. They skirted a small stream, knowing that water sources were natural gathering points. VC fighters would come here to fill cantens, to wash, to cool off. Better to avoid it entirely and accept the difficulty of moving through thicker vegetation.

They avoided a stand of bamboo because bamboo was the ultimate noise discipline failure waiting to happen. Bamboo combs knock against each other like drums when you brush them. The sound carries for hundreds of meters in quiet jungle. No professional patrol moved through bamboo if they could avoid it. Finally, as full darkness settled over the jungle, they found what they were looking for.

a termite mound, massive, easily 2 meters high and 3 meters wide, with vegetation growing up and around it. The mound was solid, built up over years by millions of insects carrying tiny particles of earth and mixing it with their saliva to create a concrete hard structure. It provided hard cover, would stop rifle rounds. It provided concealment.

The irregular shape broke up human outlines, and most importantly, it offered a clear line of sight down into the valley where the VC were establishing their cash site. The patrol settled in with careful, deliberate movements. Collins and Davis took the positions facing the cash site. Lying prone behind the termite mound, binoculars positioned, notebooks ready.

Thompson set up the radio behind them, antenna extended but disguised with foliage woven around it. Williams took the rear security position, watching their back trail, ensuring they didn’t get surprised from behind. They set out two claymore mines along likely approach routes. The claymores were insurance, last resort weapons.

Each mine contained 700 steel balls in a curved plastic case. detonated. They’d send those balls out in a 60deree arc, devastating anything within 50 meters. But using the claymores meant the mission had failed. It meant they had been detected and were fighting for their lives. The goal was to never touch those firing devices. Once positioned, they conducted final communications checks.

Davis whispered into Thompson’s ear, “Radio check. 2-hour update schedule. If I tap you twice on the shoulder, prepare to exfiltrate immediately. Three taps means contact imminent. Get ready to blow the clay moors. Thompson nodded, understanding. Then they settled in for what would be the longest night any of them had experienced.

Waiting and reconnaissance is unlike any other military activity. It’s not the waiting before battle, which has its own tension, but also a sense of impending resolution. This was open-ended waiting. Could be hours, could be days, could end in successful intelligence gathering or sudden violent contact. And through it all, you had to remain perfectly still.

The human body isn’t designed for extended motionlessness. Muscles cramp, joints stiffen, your back aches, your neck protests holding the same position for hours. Insects find you. Ants crawl across your face. Mosquitoes buzz in your ears. Leeches work their way under your clothing, but you don’t move because movement means detection, and detection means death.

Over the next 6 hours, the SAS documented everything about the VC cash site. The number of fighters, they counted 62 total, including Duke and what appeared to be a small command staff of three or four men who weren’t doing manual labor. the organization of the cash. Six storage pits total, each one carefully camouflaged after it was filled.

They mapped the location of each pit with precise 8 figure grid references. The sentry rotation schedule, the VC posted three centuries, 2-hour shifts changing at 0200, 0400, and C600 hours. Professional security, but not paranoid. They clearly felt safe in this location. The layout of the command area, Duke and his staff operated from a small shelter at the north end of the clearing, just visible through the vegetation.

They had maps spread out, were clearly planning something beyond just establishing this cache. Weapons inventory. They counted the RPG launchers, eight total, automatic weapons, mix of AKs and RPDs, and the sniper rifles, at least two SVD Dragunov rifles visible. All of this information was recorded in small, precise handwriting in waterproof notebooks using dim red filtered flashlights that barely provided enough light to see, but wouldn’t carry beyond a few meters.

All of it was transmitted back to headquarters in whispered radio reports every 2 hours. And all of it was done while remaining completely undetected, less than 150 m from an enemy force that outnumbered them 15 to1. It was in its own way a masterpiece of professional reconnaissance work. But nothing stays perfect forever. And just after dawn on the fourth day, their concealment began to fail.