On September 1st, 1939, the same morning that German tanks rolled across the Polish border, a 58-year-old brigadier general named George Catlet Marshall walked into the War Department building in Washington and took an oath that would change the course of history. He wore a white civilian suit that day, deliberately avoiding military dress so as not to appear eager for the war that had just begun in Europe.

At 10:30 that morning, in Secretary of War Harry Woodring’s office, Marshall was sworn in as Chief of Staff of the United States Army and promoted to the rank of full general. He had received word of the German invasion at 350 that morning. By the time he took his oath, Warsaw was already under bombardment.

The army he inherited was a catastrophe waiting to happen. Fewer than 190,000 soldiers served in uniform. The force ranked somewhere around 19th in the world, smaller than the armies of Portugal, Switzerland, and Belgium. To put this in perspective, Germany had just invaded Poland with over 1,500,000 troops.

The entire American army could have been swallowed by a single German army group with room to spare. Equipment dated to the previous war. Tanks were so scarce that soldiers trained with trucks bearing signs that read tank. The army possessed fewer than 500 tanks total, most of them light models that would have been destroyed in minutes against German panzers.

Artillery pieces were leftovers from 1918. Rifles were the same Springfield models that Doughboy had carried into the trenches of France two decades earlier. The nine infantry divisions that existed on paper were hollow shells. Only three divisions approached full strength. The other six averaged just 3,000 men, each instead of the 15,000 required for combat readiness.

The four armies that administered the Continental United States each had skeleton staffs of just 4400 troops. No single American division possessed full operational capability. But Marshall understood that the crisis ran deeper than equipment shortages or manpower deficits. The real problem was leadership.

The men who would have to command American soldiers in the coming war were too old, too set in their ways, and too comfortable in their positions to lead anyone into modern combat. Marshall looked at his general officers and saw what he later called considerable arterial sclerosis. The average age of generals was distressingly high.

Many had been in their current positions for years, presiding over the same small commands, attending the same social functions, fighting the same bureaucratic battles they had fought for decades. Marshall knew that sentiment and tradition could not be allowed to stand in the way of national survival. Within two years, he would force out approximately 600 officers from the army.

He would end careers, destroy friendships, and make enemies in Congress. He would be accused of gutting the army’s brains. And he would create the generation of commanders who won the Second World War. The problem Marshall faced had been building for two decades. The promotion system in the peacetime army operated almost entirely through seniority.

An officer could not advance until someone above him retired or died. Below the rank of brigadier general, there was essentially no other path upward. Merit counted for little. Initiative was often punished. The safest career strategy was to avoid mistakes, cultivate relationships with superiors, and wait. The result was a bottleneck that planners called the hump.

Approximately 4,200 officers, nearly onethird of the entire regular army officer corps, were clustered within an extraordinarily narrow age band. These men had entered the service during the First World War, received rapid wartime promotions during that conflict, and then watched their careers stagnate for the next 20 years.

The numbers told a grim story. More than 1,800 captains were in their 40s. Over a thousand officers whose age and experience qualified them for lieutenant colonel remained stuck as captains in 1940. 234 lieutenants were also in their 40s. Men who had spent more than two decades at the most junior commissioned rank.

The problem compounded itself. Young officers of talent looked at their seniors and saw no future. Many of the best left for civilian careers where ability was rewarded. Those who remained often became cynical, going through the motions of military service while waiting for retirement. The peacetime army was not attracting or retaining the talent it would need in war.

Marshall understood this problem personally. He had been a colonel during the first world war, serving as chief of operations for the first infantry division and then as chief of staff for the eighth corps and the first army. His performance had been exceptional. General John Persing, commander of the American Expeditionary Forces, considered Marshall one of the most capable officers in the army.

But after the armistice, Marshall was reduced in rank to captain. The wartime promotions evaporated. He served 15 more years before regaining the rank of colonel. The system that nearly derailed his own career was now his to reform. The generals who commanded the army in 1939 were products of this broken system. Most had reached their positions through patience rather than performance.

They had waited their turn, avoided controversy, and outlasted their competitors. The qualities that made them successful in peace time, caution, deference to superiors, mastery of bureaucratic procedure were precisely the qualities that would get men killed in war. Marshall had watched these officers for years.

He knew their strengths and weaknesses. He knew which ones could adapt and which could not. He knew which ones would rise to crisis and which would crumble under pressure. The knowledge he had accumulated over three decades of service would now determine who led the American army into battle. Marshall testified before Congress in April 1940 and laid out his philosophy with characteristic bluntness.

Leadership in the field, he said, depends to an important extent on one’s legs and stomach and nervous system. It depends on one’s ability to withstand hardships and lack of sleep and still be disposed energetically and aggressively to command men, to dominate men on the battlefield. The generals he had inherited, Marshall believed, could not meet this standard.

Most of them were too old to command troops in battle under the terrific pressure of modern war, he wrote. Their minds were set in outmoded patterns and they could not change to meet the new conditions. This was not mere theory. Marshall had studied the German campaigns in Poland and France. He had seen how speed, aggression, and initiative at all levels of command had shattered larger forces that relied on methodical approaches.

The Germans had introduced a new way of war. Their commanders made decisions in hours that would have taken traditional armies days. They exploited success ruthlessly, driving deep into enemy territory before defenders could react. The generals who would lead American soldiers against such an enemy needed to think and act differently than their predecessors.

They needed to move fast, decide fast, and accept risk. They needed physical stamina to command from the front rather than from comfortable headquarters miles behind the lines. They needed the moral courage to make hard decisions when lives hung in the balance. But removing senior officers from command was not a simple matter. The army had traditions stretching back to the revolution.

Officers had friends in Congress, connections in industry, classmates scattered throughout the service. Careers that spanned decades could not be ended without consequence. The political risks were enormous. Every general marshall pushed aside had former subordinates who would remember the slight.

Every forced retirement created enemies who might undermine him later. The wives of senior officers formed a social network in Washington that could make or break reputations. Marshall was not merely reforming the army. He was disrupting a way of life. Marshall proceeded anyway. He had faced opposition before. Early in his career, he had contradicted General Persing in a meeting and expected to be relieved.

Instead, Persing had promoted him. Marshall learned that honest counsel delivered respectfully, but firmly earned more respect than sick fancy. He applied that lesson now. He began informally at first using his authority as chief of staff to reassign officers to less critical positions to pass them over for promotion to encourage early retirement.

When these measures proved insufficient, he sought legislative authority to remove officers directly. The mechanism he created became known as the plucking board, though its official name was the removal board. The second supplemental appropriation act of 1940 gave Marshall the authority he needed by eliminating the requirement that promotions below brigadier general occur solely through seniority.

This allowed him to promote younger officers over their seniors and to push aside those who could not meet the demands of modern command. The board itself consisted of six retired general officers deliberately chosen so that serving officers would not be judging their potential rivals. Marshall asked his immediate predecessor as chief of staff, General Mailin Craig, to come out of retirement and chair the board.

Craig had served from 1935 to 1939 and was widely respected throughout the army. His presence lent legitimacy to the process. No one could accuse Marshall of settling personal scores when his own predecessor was making the decisions. Marshall’s instructions to the board established the governing philosophy. The mission, he wrote, is not to weigh a long and successful career against a failure in 1940 or 1941.

It is not the function of the board to determine how good a man he has been. Rather, it is to determine the worth and value of the individual to the army today. Critical times are upon us. The measure must be today’s performance. Officers removed by the board received one year to retire, a more dignified exit than immediate dismissal, but an unmistakable end to their careers.

The board’s authority was sweeping. It was empowered to remove from line promotion any officer for reasons deemed good and sufficient. The documented removals tell part of the story. In the summer and fall of 1941 alone, the board removed 31 colonels, 117 lieutenant colonels, 31 majors, 16 captains, and 269 national guard and reserve officers.

The lieutenant colonels were the largest group because they represented the bottleneck of World War I veterans who had been waiting decades for advancement. In the 5 years before Marshall took command, only 37 officers total had been removed from the army, an average of fewer than eight per year.

Marshall increased the removal rate more than five-fold. Ultimately, 500 colonels were forced into retirement. Marshall himself estimated that he pushed out at least 600 officers before the United States entered the war. The scale of the purge became clear during the Louisiana maneuvers of August and September 1941. These massive exercises involving nearly half a million troops across a vast swath of Louisiana and East Texas served as Marshall’s final examination for his officer corps.

The maneuvers were the largest military exercises in American history to that point. They tested not just tactical skills, but leadership under conditions that approximated combat. Units maneuvered day and night. Communications were disrupted. Plans fell apart and had to be improvised. The fog of war, or at least a reasonable approximation of it, descended on commanders who had spent decades in the predictable routine of peaceime service.

Marshall watched carefully to see which commanders could handle the stress, which could adapt to changing circumstances, which could lead men under conditions that approximated combat. He moved constantly between command posts, observing how generals reacted to setbacks, how they communicated with their staffs, how they maintained the morale of exhausted troops.

Of the 42 generals who commanded a division, core, or army during those exercises, historians estimate that only 11 would go on to hold combat commands during the war. The other 31 were pushed aside, reassigned, or retired. Marshall had seen what he needed to see. One incident during the maneuvers became legendary. George Patton, then commanding the second armored division, was supposed to be contained by a defensive line.

Instead, he led his tanks on a night march around the enemy flank, moving so fast that umpires could not keep up with him. At dawn, Patton’s tanks burst into the headquarters of Lieutenant General Hugh Drum, nominally capturing the commander of the opposing force. The maneuver was brilliant, aggressive, and exactly the kind of initiative Marshall wanted to see.

Patton had proven he could move and think faster than his opponents. Drum had proven that he could not adapt when circumstances changed unexpectedly. Both lessons would influence Marshall’s decisions about who would lead in combat. The men Marshall removed were not incompetent. Many had served honorably for decades.

Some had distinguished records from the First World War. But Marshall applied a ruthless standard. Past achievement meant nothing if an officer could not perform today. A brilliant career was irrelevant if a man’s best years were behind him. One confrontation illustrated Marshall’s approach. A general at Fort Levvenworth was ordered to update the army’s training manuals to reflect the lessons of the German campaigns in Europe.

He told Marshall the work would take 18 months. Marshall offered 3 months. The general refused. Marshall offered four months. The general said it was impossible that such comprehensive revisions could not be completed in less than a year and a half. Marshall asked him to reconsider, warning him to be very careful about that answer.

When the general insisted the timeline could not be shortened, Marshall’s response was immediate. I am sorry. Then you are relieved. The incident revealed something essential about Marshall’s leadership. He did not raise his voice. He did not threaten. He simply stated the requirement and accepted no excuses. Officers who could not meet his standards were removed regardless of their previous service or their connections.

The manuals, incidentally, were completed in 4 months by other officers. Marshall showed the same coldness toward personal friends. One general ordered to France on an important mission explained that he could not depart quickly because his wife was away and household furniture remained unpacked. Marshall called him personally to confirm this was his position.

When the general said it was, Marshall replied, “Well, my god man, we are at war and you are a general. I am sorry too, but you will be retired tomorrow.” The highest profile casualty of Marshall’s reforms was Lieutenant General Hugh Drum. Though his fate came through being passed over rather than formally removed, Drum had reached the rank of major general in 1930 and held nearly every top position below chief of staff.

He had been chief of staff for the First Army in France during the World War Douglas MacArthur claimed he had virtually run the army. By every measure of seniority and experience, Drum should have become chief of staff. But Drum had promoted his own cause so vigorously that he alienated President Franklin Roosevelt. He lobbied openly for the position, cultivated newspaper coverage, and made clear his expectation that the job was his due.

When the appointment was made in 1939, Roosevelt passed over Drum and 32 other senior officers to select Marshall, who was 34th in overall army seniority. Marshall had been outranked by 21 major generals and 11 brigadier generals. Drum never forgave the slight and never stopped maneuvering for high command. During the war, he was summoned to Washington expecting to receive command of American forces in Europe based on a conversation with Roosevelt from 1939.

Instead, Marshall offered him the position of chief of staff to Chiang Kai-shek in China. Drum objected strenuously. He said the mission was nebulous, uncertain, and indefinite. He complained about serving three masters, including Chang, the British, and Washington. When Marshall said no large American forces would go to China, Drum remarked that he would be wasted in a minor post.

Marshall concluded that Drum lacked enthusiasm for the assignment and recommended against sending him. Joseph Stillwell was selected instead on January 14th, 1942. When Stillwell was asked if he would accept the difficult China command, his response was simple. I will go where I am sent. Drum was relegated to commanding the Eastern Defense Command, essentially home defense duty on the American East Coast.

He reached mandatory retirement age at 64 in September 1943. He received his second distinguished service medal at a ceremony where Marshall himself read the citation, but he never received the combat command he had sought for decades. The irony is that Fort Drum in New York is named in his honor. No military installation bears Marshall’s name.

The removals made room for the officers Marshall believed could win the war. But identifying those officers required a different kind of talent, the ability to recognize potential that had not yet been proven to see what men might become rather than what they had already done. A legend grew up around Marshall’s methods.

People said he kept a little black book containing the names of promising officers he had observed throughout his career. The story was repeated so often that it became accepted as fact. Marshall’s own biographer, Forest Pogue, mentioned it in his work on page 95 of the second volume, but the Little Black Book never existed. The George C.

Marshall Foundation has confirmed that no such notebook was ever found among Marshall’s papers. When Dr. Larry Bland, the editor of the papers of George Catlet Marshall, asked Pogue directly on two separate occasions whether Marshall kept such a book, Pogue confirmed that he did not. Pogue admitted that he had repeated the myth when it was presumed real and said he was sorry he had included it in his writing because it gave the story authority it did not deserve.

What Marshall actually possessed was an extraordinary memory. Throughout his career he had observed officers at key vantage points at Fort Benning where he served as assistant commandant from 1927 to 1932. He had watched hundreds of officers teach, learn, and lead in China, in Washington, and in various staff positions.

He had noted who showed initiative, and who waited for orders, who could think clearly under pressure, and who froze, who could inspire men, and who merely commanded them. The list of promising officers existed entirely in his mind. He could recall conversations from years earlier, impressions formed in passing, potential glimpsed in a single exercise or staff meeting.

This mental catalog accumulated over decades would determine who led American forces into battle. During his years at Fort Benning, approximately 150 future generals attended the infantry school with about 50 serving on the faculty. Marshall watched them all. He assigned them challenging problems and observed how they responded. He noted who asked the right questions and who accepted easy answers.

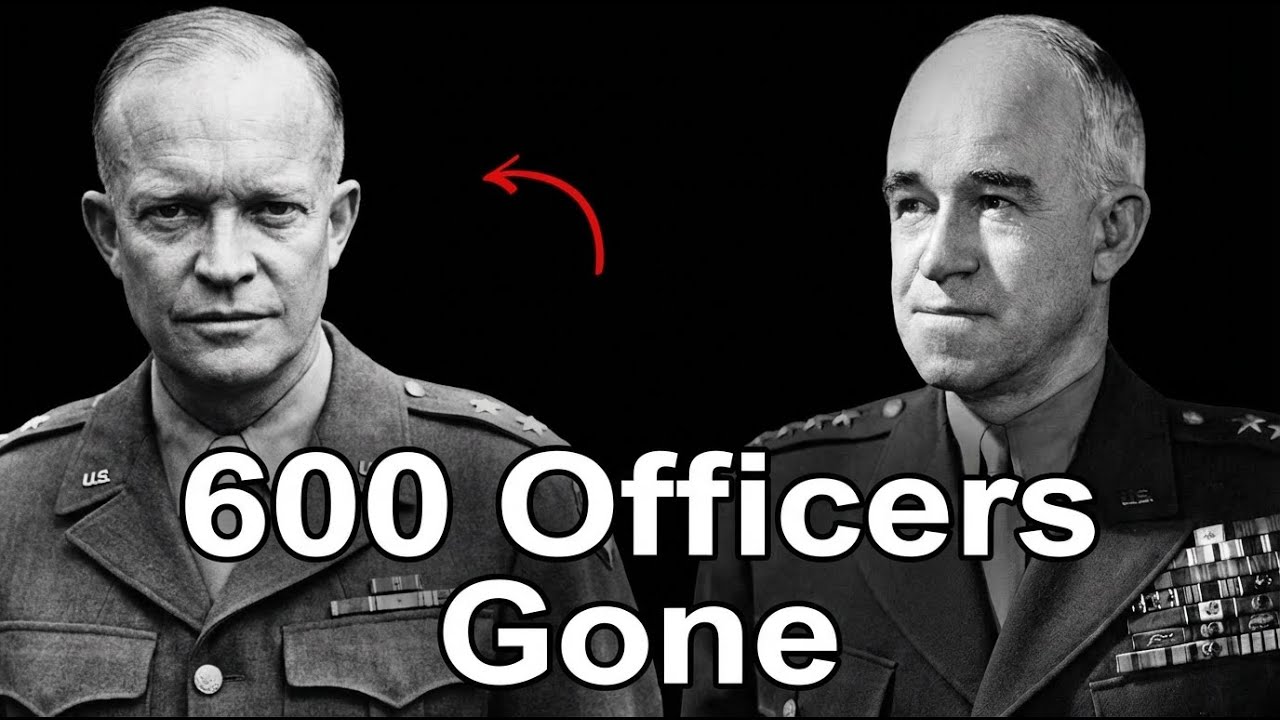

These officers became known as the Marshall men, and their careers would accelerate dramatically once Marshall gained the power to promote them. The selection of Dwight Eisenhower demonstrated Marshall’s methods in action. Their first meaningful contact came in 1930 when Marshall was impressed by a young major working on the American Battlefield Monuments Commission staff who had helped General John Persing revise his memoirs.

The work required tact intelligence and the ability to manage a difficult superior. Marshall noted these qualities and remembered the young officer’s name. Marshall offered Eisenhower a position on the Fort Benning faculty. Eisenhower politely declined because he already had orders for a coveted general staff assignment in Washington.

The refusal did not offend Marshall. If anything, it demonstrated that Eisenhower could make decisions and stick to them. Their paths crossed again at the Louisiana maneuvers in September 1941. Eisenhower was then a lieutenant colonel serving as chief of staff for Lieutenant General Walter Krueger’s Third Army. His performance caught Marshall’s attention.

Eisenhower had helped plan operations that consistently outmaneuvered the opposing force. His staff work was meticulous but not rigid. When plans needed to change, he changed them. The pivotal moment came on December 14th, 1941, exactly one week after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Marshall summoned Eisenhower to Washington.

Eisenhower flew from Fort Sam Houston in Texas, arriving exhausted after delays and bad weather. It was the first time he had spoken to Marshall for more than 2 minutes. Marshall presented a grim overview of the situation in the Pacific. The Philippines, where Eisenhower had served four years under MacArthur, were under attack. The Pacific fleet had been devastated at Pearl Harbor.

Japanese forces were advancing across Southeast Asia. The strategic situation appeared desperate. Then Marshall posed a test. What should be our general line of action? Eisenhower asked for a few hours and a desk. Marshall provided both. Several hours later, Eisenhower returned with a memorandum that acknowledged the Philippines could not be saved, but argued they could not be abandoned either.

The United States had to make every effort to support the defenders, even if the effort was ultimately futile because abandoning them would destroy American credibility with allies throughout the Pacific. He recommended building up Australia as a base for Pacific operations. This analysis became the core Pacific strategy. More importantly, it demonstrated exactly what Marshall wanted to see.

Eisenhower had not asked for more information. He had not requested a committee to study the problem. He had not hedged his conclusions with qualifications. He had analyzed the situation, reached a decision, and presented a clear recommendation. Marshall’s response revealed his philosophy. Eisenhower, he said, the department is filled with able men who analyze their problems well, but feel always compelled to bring them to me for final solution.

I must have assistants who will solve their own problems and tell me later what they have done. Eisenhower had passed the test. Marshall assigned him to the war plans division overseeing the Philippines and Far East. By February 1942, just two months later, Eisenhower was chief of the entire war plans division.

His subsequent rise was the fastest of any general in the Second World War. From left tenant colonel in December 1941, he became a five-star general of the army by December 1944, a promotion that came just 4 days after Marshall himself received his fifth star. George Patton presented a different kind of challenge. Marshall had known Patton since the First World War and had renewed the friendship at Fort Meyer in late 1938 when Patton commanded the Third Cavalry.

The two men were a study in contrasts. Marshall was reserved, methodical, and selfacing. Patton was flamboyant, impulsive, and utterly convinced of his own destiny. Marshall regarded Patton as the allies best fighting general, but recognized that he required management. Patton, Marshall observed, needs a break to slow him down because he is apt to coast at breakneck speed, propelled by his enthusiasm and exuberance.

Catherine Marshall, the general’s wife, once told Patton that he could not talk the way he did. George, you say these outrageous things and then you look at me to see if I am going to smile, she said. A general cannot talk in any such wild way. At 54 years old, Patton fell into the category of officers who might have been pushed aside under Marshall’s age standards.

He survived the plucking board’s review only because he demonstrated the energy and drive of a much younger man. His performance in the Louisiana maneuvers, where his armored division ran circles around the opposition, proved that age had not diminished his capabilities. Marshall elevated Patton from colonel in July 1938 to fourstar general by April 1945.

The journey between those ranks was tumultuous. Patton’s mouth got him into trouble repeatedly. His actions sometimes bordered on insubordination, but Marshall protected him because he recognized that Patton was irreplaceable. Twice during the war, Marshall intervened to save Patton’s career.

In Sicily, Patton slapped two soldiers suffering from combat fatigue, an incident that became a scandal when reporters learned of it. Eisenhower, who commanded the Mediterranean theater, considered sending Patton home in disgrace. Marshall counseledled patience. Patton was too valuable to lose. After the Nutsford affair in England, when Patton made impolitic remarks suggesting that the United States and Britain would rule the postwar world with no mention of the Soviet Union, Marshall again protected him. The incident nearly cost Patton his

command on the eve of the Normandy invasion. Marshall’s intervention kept him in place. Omar Bradley represented yet another path to high command. He had served as a tactics instructor at Fort Benning. During Marshall’s tenure as assistant commandant, the two men had worked closely together, and Marshall had observed Bradley’s teaching methods, his treatment of students, and his approach to military problems.

Marshall described Bradley as quiet, unassuming, capable, with sound common sense. These were not flashy qualities, but they were the qualities Marshall valued most. Bradley did not seek attention. He did not promote himself. He simply did his job with steady competence. Bradley later wrote that no man had a greater influence on him personally or professionally than George Marshall.

The relationship shaped Bradley’s entire career and his approach to command. Bradley rose from Brigadier General in February 1941 to fourstar general and commander of the 12th Army Group, the largest American field command in history. More than 1,300,000 soldiers served under his command during the campaigns in France and Germany.

He would later become the first chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, a position that placed him at the pinnacle of the American military establishment. Joseph Stillwell, known as Vinegar Joe for his sharp tongue and acid personality, impressed Marshall so deeply that Marshall held open the position of chief of the tactical section at Fort Benning for a full year until Stillwell became available.

Other officers wanted the job. Marshall waited for the man he wanted. Marshall called Stillwell possessed of a genius for instruction and one of the exceptionally brilliant and cultured men of the army. The description of Stillwell as cultured might have surprised those who knew only his crusty exterior, but Stillwell spoke Chinese fluently, had studied Chinese history and literature, and understood Asia better than almost any American officer of his generation.

When Marshall needed someone to handle the impossible China assignment that Drum had rejected, Stillwell was his choice. The mission proved every bit as difficult as Drum had feared. Stillwell fought with Chiang Kaishek, clashed with the British, and watched his forces suffer repeated defeats. But he never quit. He never asked to be relieved.

He did exactly what Marshall had asked of him. The roster of commanders Marshall identified and elevated reads like a history of American victory in the Second World War. Mark Clark led the Fifth Army in Italy. Courtney Hodges commanded the First Army in Europe. Jacob Divas led the sixth army group in the invasion of southern France.

Jay Lorton Collins became one of the most aggressive core commanders in the European theater. Lucian Truscott led divisions and core in North Africa, Sicily, Italy, and southern France. Matthew Rididgeway commanded airborne forces in Normandy and later led the 18th Airborne Corps. Walter Krueger directed the Sixth Army across the Pacific.

These men led American forces from the beaches of North Africa to the heart of Germany. From the jungles of Guadal Canal to the Philippines and beyond. They defeated two of the most formidable military powers in history simultaneously. The consequences of Marshall’s reforms became clear when American forces were measured against armies that had not undergone similar transformation.

France offered the most devastating contrast. When Germany attacked in May 1940, the French army possessed more tanks than the Vermacht. It had adequate manpower with approximately 5 million men under arms. Its defensive fortifications along the Majino line were engineering marvels that represented the most sophisticated military construction of the age.

On paper, France should have been able to resist the German onslaught. But French leadership was aged, rigid, and trapped in the patterns of the previous war. General Maurice Gamlan, the French commander-in-chief, was 67 years old during the campaign. He had established his headquarters at the Chateau Deansen, a medieval fortress without modern communications equipment.

The headquarters had no radio. Orders traveled by motorcycle courier, a method that belonged to 1914, not 1940. Gamalin had decreed in 1935 that the high command was the sole arbiter for doctrine. All articles, lectures, and books by serving officers required approval before publication. This effectively stifled innovation and ensured that French military thinking remained frozen in the patterns of the first world war.

Officers who questioned established doctrine risked their careers. When the Germans punched through the Arden’s forest, an area Gamalin had left defended by only 10 reserve divisions because he considered it impossible to armor, the French command structure collapsed. Gamalin sat in what observers called tragic immobility.

Unable to issue decisive orders as his armies disintegrated. The speed of the German advance overwhelmed a command system designed for the deliberate pace of trench warfare. His replacement, General Maxim Reagand, was 73 years old, even older than Gamlan. Reagand arrived on May 19th, 9 days after the German attack began, when the breakthrough was already complete.

Within a week, he was displaying pessimism that could have been interpreted as defeatism. The battle was lost before he could influence it. France fell in 6 weeks. Approximately 60,000 French soldiers died between May and June of 1940. The cause was not lack of courage among the troops or shortage of equipment.

French soldiers fought bravely in many engagements. French tanks were often superior to their German counterparts. The cause was leadership that could not adapt to the speed and violence of modern warfare. Britain fared only marginally better in the early years of the war. The British Officer Corps maintained a rigid class-based selection system in which 89% of officer candidates at the Royal Military College at Sandhurst in 1939 came from expensive private schools.

The system produced capable administrators but discouraged the kind of aggressive initiative that modern warfare demanded. British reforms came only after battlefield defeats forced change. The General Service Corps Scheme, which attempted to broaden the base of officer recruitment, was not introduced until July 1942, nearly 3 years after the war began.

By then, Britain had suffered disasters in France, North Africa, and the Far East. Germany, ironically, had a more merit-based officer evaluation system than either France or Britain. German officers were rated in seven categories ranging from suitable for vermach high command to already unsuitable for current position.

Junior officers could command battle groups over their seniors based on tactical necessity. This flexibility combined with a doctrine that emphasized initiative at all levels gave the German army decisive advantages in the early years of the war. But German flexibility had limits. Adolf Hitler increasingly interfered with military operations, overruling his generals based on intuition rather than analysis.

Commanders who disagreed with the furer risked their careers and sometimes their lives. The honest assessments that might have corrected German strategy were suppressed in favor of reports that told Hitler what he wanted to hear. Marshall’s critics charged that he was destroying institutional memory, that he was throwing away decades of accumulated experience, that he was promoting untested men over proven leaders.

Service newspapers accused him of getting rid of all the brains of the army. Marshall’s response was characteristically dry. I could not reply, he said, that I was eliminating considerable arterial sclerosis. Congressional opposition centered on National Guard generals with political connections.

The guard was deeply intertwined with state politics. Guard generals often owed their positions to governors and legislators rather than military merit. When politicians questioned his efforts to replace guard division leadership, Marshall’s response was blunt. I am not going to leave him in command of that division, he said of one politically connected general.

So I will put it to you this way. If he stays, I go, and if I stay, he goes. The politician backed down. Marshall’s willingness to stake his position on personnel decisions gave him leverage that few chiefs of staff had possessed. When Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter passed along criticism from a friend in the Army Reserve, Marshall replied tartly, “Most of our senior officers on such duty are Deadwood and should be eliminated from the service as rapidly as possible.

” He did not soften his views for friends of the powerful. The opposition never stopped Marshall because he possessed something his critics lacked, the absolute confidence of President Roosevelt. The president had selected Marshall over 33 more senior officers, precisely because he recognized in Marshall the moral courage to make hard decisions.

Roosevelt backed his chief of staff consistently, even when the political costs were significant. Marshall’s selections were not infallible. He made mistakes and he learned from them. He was especially fond of Lloyd Fredendle, calling him one of the best and remarking that you could see determination all over his face. Fredendall commanded the largest task force in Operation Torch, the Allied invasion of North Africa in November 1942.

At Casarine Pass in February 1943, Fredendal proved disastrous. His command post was located 70 mi behind the front lines in an elaborate underground bunker that his engineers had spent weeks constructing while combat units needed their skills elsewhere. He issued confusing orders using a personal code that his subordinates could not understand.

When German forces attacked, American units were positioned poorly and coordinated worse. The result was the worst American defeat of the European War. More than 6,000 American soldiers were killed, wounded, or captured. Equipment losses were staggering. German commanders who had wondered whether American troops could fight concluded that their doubts had been confirmed.

Both Marshall and Eisenhower came to regret the Fredendall selection. But the system Marshall had created allowed for correction. Fredendall was relieved and replaced by Patton, who transformed the defeated corps into a fighting force within weeks. The ability to remove failing commanders without destroying their careers or creating political crisis was itself a product of Marshall’s reforms.

Fredendor was not disgraced. He was sent back to the United States to train new troops, a position where his organizational skills could be useful without the pressures of combat command. His experience, even failed experience, was not wasted. During the war, 16 army division commanders were relieved for cause along with at least five core commanders.

Critically, the system permitted second chances. At least five generals who were relieved of combat command were later given another division to lead. Orlando Ward commanded the 20th Armored Division in 1945 after being relieved earlier in the war. Terry Allen led the 104th Infantry Division through the end of the war after his removal from the First Infantry Division.

This flexibility distinguished the American approach from both the German and the British systems. German commanders who failed were often shot or imprisoned. British commanders who failed were rarely given second opportunities. The American system treated failure as information rather than disgrace, allowing the army to learn from mistakes rather than simply punish them.

The transformation Marshall achieved can be measured in numbers. When he took command in September 1939, the army had fewer than 190,000 soldiers organized into six divisions with only four in the continental United States, one in Hawaii, and one in the Philippines. By the end of 1940, the number had grown to 269,000.

By the end of 1941, it exceeded 1,400,000. By 1943, nearly 7 million. At its peak in March 1945, the United States Army numbered more than 8 million soldiers organized into 91 divisions. This expansion required a corresponding increase in officers. Men who had been lieutenants in 1940 were colonels by 1944. The bottleneck that had strangled careers for two decades was shattered by the demands of global war.

The young officers Marshall had identified and protected now led divisions and core into battle. The army that stormed the beaches of Normandy on June 6th, 1944 bore no resemblance to the force Marshall had inherited 5 years earlier. American soldiers crossed the English Channel in landing craft designed and built in American shipyards.

They were supported by aircraft manufactured in American factories. They carried weapons produced by an industrial mobilization that had transformed the American economy. But equipment alone did not win battles. The men who led those soldiers had been selected, trained, and tested by the system Marshall created.

They had survived the plucking board. They had proven themselves in maneuvers and in combat. They were the best officers the American military could produce, and they led from the front. Winston Churchill called Marshall the true organizer of victory and the noblest Roman of them all. Eisenhower declared that our army and people have never been so indebted to any soldier.

Harry Truman said simply that millions of Americans gave their country outstanding service. George C. Marshall gave it victory. Time magazine named Marshall man of the year twice in 1943 and 1947. He became the first and only career soldier to receive the Nobel Peace Prize awarded in 1953 for the Marshall Plan that rebuilt Europe after the war.

He served as both Secretary of State and Secretary of Defense. The only person in American history to hold both positions. The officers Marshall removed faded into obscurity. Their names appear in no histories of the war. Their contributions, whatever they might have been, remained unmade. Some accepted their fate with dignity, understanding that the mission was greater than any individual career.

Others harbored resentment for the rest of their lives, never accepting that their time had passed. The officers Marshall promoted became legends. Eisenhower served two terms as president of the United States. Bradley became a five-star general and the most respected military figure of the postwar era.

Patton died in a car accident just months after the German surrender, but his name became synonymous with aggressive leadership. The Marshall men shaped American military doctrine and defense policy for a generation after the war ended. Marshall himself sought no glory. When Roosevelt died in April 1945 and Harry Truman became president, many assumed Marshall would receive command of the invasion of Japan or some other prestigious assignment.

Instead, Marshall remained in Washington, coordinating the global war effort from his desk. When Eisenhower was selected to command the Normandy invasion, a position Marshall had wanted, he accepted the decision without complaint. Truman offered Marshall the chance to become the military governor of Germany after the war. Marshall declined.

He had seen enough of war. He wanted to go home to his garden in Leburg, Virginia, and spend time with his wife, Catherine. But retirement proved impossible. Truman needed him in China as a special envoy, then as Secretary of State, then as Secretary of Defense during the Korean War.

Marshall served until his health failed, always answering when his country called. The lesson of Marshall’s officer purge extends beyond military affairs. Organizations of all kinds faced the same challenge he confronted. How do you remove people who have done nothing wrong except grow old in their positions? How do you make room for new talent when existing leaders have earned their places through years of faithful service? How do you balance loyalty to individuals against responsibility to the institution? Marshall’s answer was uncompromising.

The measure must be today’s performance. Past achievements, personal friendships, political connections, none of these could be allowed to outweigh current capability. The mission was too important. The stakes were too high. Men would die if leaders could not lead. Marshall stated his philosophy in words that deserve to be remembered.

The truly great leader overcomes all difficulties, he said. Campaigns and battles are nothing but a long series of difficulties to be overcome. The lack of equipment, the lack of food, the lack of this or that are only excuses. The real leader displays his quality in his triumphs over adversity. however great it may be.

He had another saying that captured his approach to selecting leaders. If leadership depends purely on seniority, he said, you are defeated before you start. You give a good leader very little and he will succeed. You give mediocrity a great deal and they will fail. This principle demanding excellence, accepting no excuses, measuring leaders by results, transformed an army ranked 19th in the world into the force that defeated Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan.

It remains Marshall’s enduring legacy. If you found this story compelling, please take a moment to like this video. It helps us share more forgotten stories from the Second World War. Subscribe to stay connected with these untold histories. Each one matters. Each one deserves to be remembered.

And we would love to hear from you. Leave a comment below telling us where you are watching from. Our community spans the globe. From veterans to history enthusiasts, you are part of something special here. Thank you for watching and thank you for keeping these stories alive.