They called Oshwitz a factory of death, a place where names were erased, where numbers replaced faces, where mercy had no function. The SS believed they controlled every breath taken inside those fences. They believed no one could defy them and live. They were wrong because in one corner of that camp, in a barrack soaked with blood, filth, and despair, stood a woman they could not break.

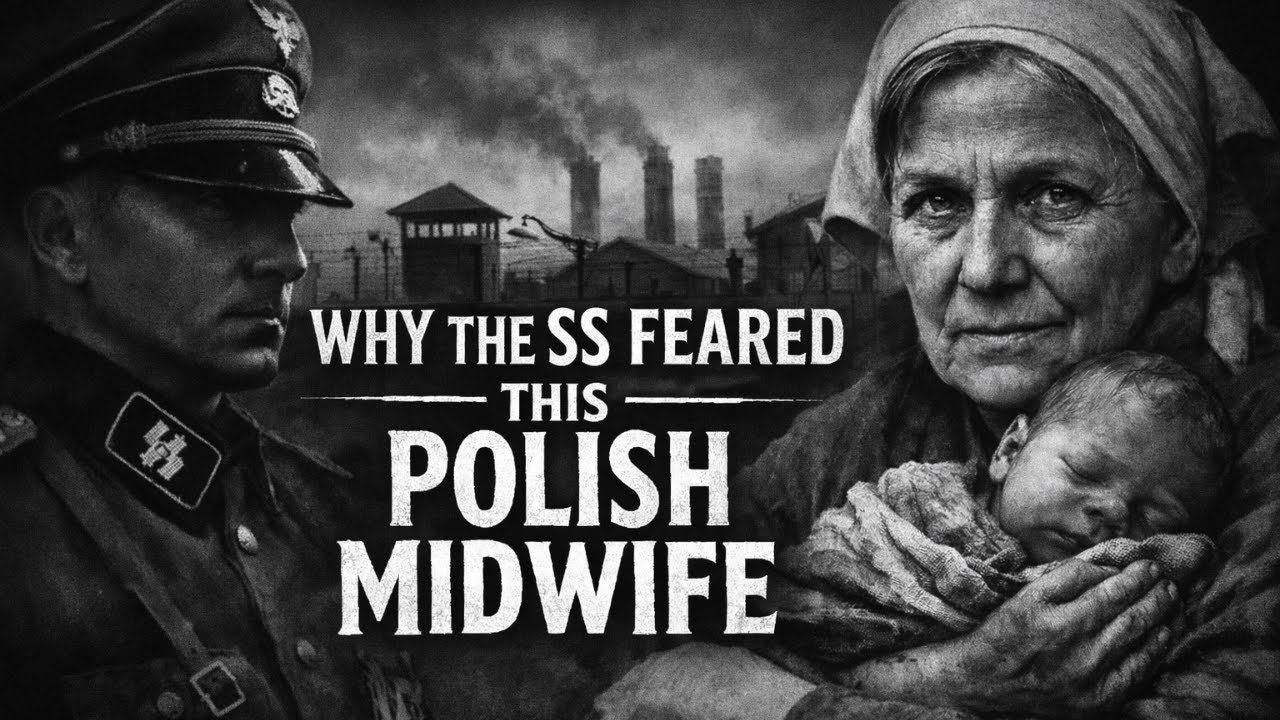

A Polish midwife, unarmed, starving, surrounded by death. And for reasons they never fully understood, the SS learned to fear her. Her name was Stannislawa Lechinska. Before the uniforms, before the dogs, before the smoke rising from the chimneys, she lived an ordinary life, a quiet one. She was born in 1996 in a Poland that did not officially exist on maps, carved apart by empires.

Her childhood was shaped by hardship, but also by faith, discipline, and an unshakable sense of duty. She trained as a midwife in luge, not a revolutionary, not a soldier, a woman who helped bring children into the world. She learned how to steady trembling hands, how to listen for breath, how to fight panic with calm words.

Her work was intimate, fragile, and sacred. By the time she married and raised children of her own, Europe was already sliding toward catastrophe. When Germany invaded Poland in 1939, brutality became law overnight. Public executions, mass arrests, homes torn apart. Stannislawa did what countless Poles did. She helped where she could. She hid Jews. She forged documents.

She passed messages. It was enough. In 1943, the Gestapo came for her. There was no trial, no explanation. She was arrested along with her daughter and thrown into the machinery of the Reich. The cattle car doors slammed shut. The air disappeared. Days blurred together. Screams, prayers, silence. When the doors opened again, the sign greeted them with cruel mockery.

Arbite mocked Fry. Oshwitz. She was stripped, shaved, numbered. Her name vanished, replaced by digits sewn onto filthy fabric. Her daughter was torn from her. She never knew if she was alive or dead. Stannislaw was assigned to the women’s camp. Block after block of skeletal figures, eyes hollow, bodies already half gone.

Then the SS discovered her profession, midwife. In Oshwitz, pregnancy was a crime, a defect to be eliminated. Jewish infants were drowned, smashed, or injected with poison moments after birth. Polish infants were usually killed as well, unless they appeared German enough to be stolen and sent for re-education. Childbirth did not mean hope here.

It meant terror. The camp already had a system, a system of murder, and into that system walked Stannislawa Lechinska. She was ordered to assist births under the supervision of SS doctors. She saw immediately what they expected of her, obedience, silence, participation. They expected her to help kill newborns.

She refused. Not quietly, not indirectly. She refused outright. She told the SS that as a midwife she would not harm a child, not under orders, not under threat, not in Awitz. This was not defiance that earned applause. It earned death. The SS executed prisoners for far less. A blance held too long, a step out of line. But something strange happened.

They did not kill her. They threatened her. They screamed. They humiliated her. They struck her. But they did not execute her. Instead, they forced her to work. Births in Oshwitz took place in conditions designed to kill. No clean water, no bandages, no disinfectant, no privacy. Women gave birth on wooden planks soaked with blood and excrement.

Lice crawled across newborn skin. Rats watched from the corners. Stannislawa washed infants in filthy water. She tore strips from her own clothing to wrap them. She whispered prayers into ears that might only hear sound for a few minutes. And something else happened. Not a single child she delivered died during birth. Not one.

In a camp designed to exterminate life, her hands preserved it. The SS noticed. Doctors who considered prisoners disposable began to observe her with suspicion. She did not panic. She did not rush. She did not collapse. She worked with a calm that felt unnatural in a place like Awitz. She spoke to the mothers. She told them when to breathe.

She held their faces even when those mothers knew what came next. Because after birth came the selection. SS guards arrived. If the child was Jewish, it was usually killed immediately. If it was Polish, sometimes it was drowned. Sometimes it was left to starve. Stannislawa watched this over and over again.

And each time she did the same thing. She delivered the child. She cleaned it. She baptized it with a drop of water if she could. She treated every birth as sacred, even in hell. This was not passive resistance. It was moral warfare. And it unsettled the SS more than violence ever could because she did not scream at them.

She did not curse them. She did not beg. She simply did not comply. There is a particular kind of courage that terrifies tyrants. Not the kind that shouts, the kind that stands quietly and refuses to move. The SS began to avoid the birthing barrack when she was there. They mocked her faith. They laughed at her rituals.

But they did not stop her. They could not understand her. She was starving like everyone else. She was beaten like everyone else. She watched death every day. And still she chose life. Word spread through the camp among the women. If you are pregnant, pray you are sent to her. If you give birth, pray she is there.

Mothers clung to her voice during labor like a lifeline. Some asked her impossible questions. Will my baby live? Will I see my child again? She never lied, but she never surrendered to despair. She told them the truth with dignity. She told them their child mattered, that their suffering was seen. For many, those words were the last kindness they ever heard.

The SS feared uprisings. They feared sabotage. They feared escape. But what they truly feared was the collapse of the system they built. A system that depended on dehumanization. And Stannislawa refused to dehumanize anyone. Not the mothers, not the infants, not even herself. Her existence was proof that Awitz had failed to erase the soul.

As transports arrived and chimneys burned day and night, she continued. Hundreds of births, hundreds of infants delivered into a world that did not want them. Each one a silent act of rebellion. each one a reminder that life could still appear where death ruled. And slowly, quietly, the SS learned something dangerous. They could kill bodies. They could starve flesh.

They could terrorize entire nations. But there was one thing they could not control. A woman who refused to surrender her conscience. By the time part one of her story ends, Awitz still stands. The chimney still smoke, the guards still patrol. But inside that camp, fear has shifted. Not among the prisoners, among the men who believed they were gods.

Because somewhere in their kingdom of death, a midwife was still delivering life. The SS never wrote her name in their reports. There was no category for what she represented. She was not an insurgent, not a sabotur, not a spy. She was more dangerous than all of them because she made Ashvitz human. As the months passed, the war outside the barbed wire began to turn.

The thunder of artillery grew closer. Bombers crossed the sky. Rumors moved faster than rations. The SS grew harsher. More executions, less food, shorter tempers. Pregnant women became an inconvenience they no longer wanted to tolerate. Orders shifted. Sometimes newborns were killed immediately. Sometimes they were left to die unattended.

Stannis Lawa never stopped. She worked until her legs shook, until her hands cracked and bled, until fever blurred her vision. She delivered babies while collapsing from hunger. She delivered babies during air raids. She delivered babies knowing most would not survive the day.

Still, she delivered them as if they mattered. There is a moment in every system of terror where cruelty becomes routine, where murder stops feeling like an act and becomes a process. That is the moment Stannislawa disrupted. Because every birth forced the SS to confront what they were destroying. A crying infant cannot be reduced to a number.

A newborn’s breath cannot be argued away by ideology. And so the SS hardened themselves. They ordered drownings. They ordered injections. They ordered selections with colder efficiency. But they never broke her. Not once did she assist in killing a child. Not once did she look away from a mother in pain. Not once did she abandon her oath.

Some SS doctors tried to intimidate her with threats of execution. She answered calmly, “Do what you must. I will not.” It was not defiance fueled by rage. It was certainty. By late 1944, something unprecedented happened. The orders changed again. Newborns were no longer automatically killed. Not out of mercy, out of logistics.

The Reich was collapsing. Resources were stretched thin. Chaos crept into even the most disciplined systems. Some infants were allowed to live barely. They were left naked, unfed, unrecorded. And once again, Stannis Lawa stepped into the gap. She begged scraps of cloth from other prisoners. She organized women to share crumbs of bread.

She taught mothers how to hide infants during inspections. She created a fragile, invisible network of survival. By the time Ashvitz was evacuated in January 1945, over 3,000 babies had been delivered by her hands. 3,000. Of those, most did not survive the camp, but hundreds did. Hundreds left Achvitz alive because one woman refused to accept the rules of hell.

When the SS forced the evacuation marches, when prisoners were driven into the snow at gunpoint, Stannislawa marched too. She survived. She walked out of Ashvitz alive. Liberation did not arrive with celebration. It arrived with silence, with bodies too weak to react, with minds that could barely comprehend survival.

When she returned to Poland, there was no parade, no medals, no headlines. She went home and did what she had always done. She became a midwife again. For decades she spoke little about Ashvitz, not because she forgot, but because memory carried weight. When she did speak, she did not describe the SS in detail. She did not dwell on their faces or their cruelty.

She spoke about the mothers, about the children, about the sacredness of life even in a place designed to destroy it. Eventually, survivors began to speak too. Women who had given birth in Ashvitz, children who had survived against all odds. They remembered her voice, her hands, her calm. They remembered the woman who looked at them and treated them like human beings.

Stannislawa wrote a report years later not to accuse, not to condemn, to bear witness. She described births without water, without light, without hope. She described infants dying from cold, from hunger, from cruelty that no language could justify. But even in her writing there was restraint, no hatred, no revenge, only truth.

She lived long enough to see the world try to understand Achvitz, museums built, books written, trials held. She lived long enough to know that evil could be documented, but goodness often went unnoticed. Stannislawa Lechinska died in 1974 quietly without fame. No statue marked her passing.

No state funeral honored her life. Yet her legacy did not fade because somewhere men and women walked the earth who had once been born in Avitz. They carried lives she had delivered. They carried proof that the SS had failed. The Nazis believed fear was absolute, that terror could rewrite human nature. They believed morality was fragile. They were wrong.

Stannis Lawa proved that conscience could survive starvation. That dignity could survive humiliation, that compassion could survive systematic murder. She never carried a weapon. She never planned an escape. She never raised her voice. And yet the SS feared her because she represented the one thing their system could not tolerate, a moral boundary that could not be crossed.

In the end, Ashvitz did not fall because of a midwife, but it was exposed by one. Exposed as a place where even absolute power could be defied by a single human choice to help, to care, to refuse. When we ask how evil spreads, we often look for monsters. But when we ask how it is resisted, the answer is usually quieter.

A woman doing her job, a promise kept, a life protected for as long as possible. Stannislawa Lechinska never believed she was a hero. She believed she was responsible. And in a world that had abandoned responsibility, that belief became revolutionary. The SS feared guns. They feared rebellion. They feared losing control. But what they feared most was a woman who could not be made to forget what was right.

Because as long as she stood in Achvitz, life had not surrendered and neither had humanity.