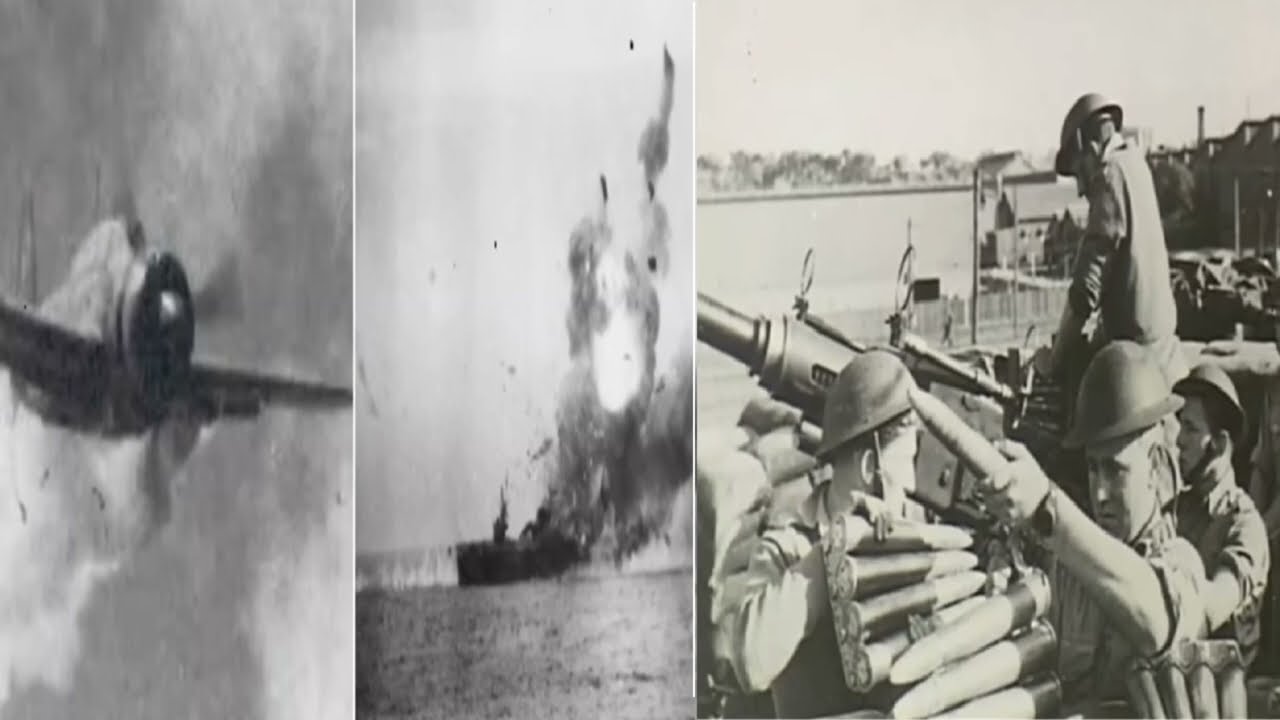

In October 1944, Gunner’s mate Tommy Rodriguez gripped his anti-aircraft gun aboard the USS Enterprise as Japanese kamicazi pilot screen toward his ship at over 400 mph. He fired burst after burst, watching helplessly as his tracers stre harmlessly behind the diving aircraft. Like thousands of other American gunners, Rodriguez faced a brutal mathematical reality.

Hitting a fastmoving maneuvering target required split-second calculations that human reflexes simply couldn’t perform. The statistics were catastrophic. American anti-aircraft guns achieved a kill rate of just 3.2%. only three enemy aircraft destroyed for every 100 shells fired. By October 1944, the US Navy had fired over 400,000 rounds in combat with minimal results.

Japanese pilots attacked with near impunity. And with the introduction of kamicazi tactics, every enemy plane became a guided missile piloted by someone willing to die. What Rodriguez didn’t know was that his ship carried a revolutionary new weapon, a shoe box-sized device that Navy brass had initially dismissed as insane and impossible.

This invention created by an MIT professor with no military credentials, would transform naval warfare, and ultimately save an estimated 50,000 American lives. The impossible challenge. The problem of hitting fastmoving aircraft had plagued military engineers since World War II. By 1941, American guns could fire shells at tremendous velocities, but accuracy remained abysmal.

The fundamental challenge was lead calculation, determining where to aim when shooting at a moving target. A shell fired from a 40 mm gun takes approximately 3 seconds to reach an aircraft at 4,000 yd. In those 3 seconds, an enemy plane traveling 400 mph moves nearly 1,800 ft. Gunners had to aim at empty sky, hoping their shells and the target would arrive at the same point simultaneously.

Traditional gun sights were simple iron rings showing where the weapon pointed. But they couldn’t account for targets that dove, climbed, and spiraled unpredictably. The Navy’s Bureau of Ordinance tried multiple solutions. Massive mechanical computers requiring teams of operators. Automated tracking systems that proved too unreliable.

But nothing worked in real combat conditions. Admiral William Hollyy captured the prevailing wisdom in 1942. Anti-aircraft gunnery is more art than science. We can teach our boys to point and shoot, but we cannot teach machines to think like fighter pilots. By spring 1941, the situation had become desperate.

American warships carried guns that could barely hit their targets, leaving them vulnerable as war approached. The Navy’s institutional blindness made things worse. Senior officers blamed gunner training rather than acknowledging fundamental technological limitations, while failed conventional solutions continued receiving funding.

The unconventional genius Dr. Charles Stark. Doc Draper possessed no military credentials, no weapons training, and no naval gunnery experience. At 38, his specialty was precision instrumentation, specifically gyroscopic devices that measured rotation and orientation with microscopic accuracy.

While Navy engineers designed roomsiz fire control computers, Draper worked with spinning wheels the size of silver dollars. The breakthrough came during a May 1940 lunch with pilots and engineers from Sperry Gyroscope Company. Discussion turned to the difficulty of hitting moving targets and someone mentioned that French gunners couldn’t hit anything moving fast.

Draper stopped eating and stared at his gyroscopic turn indicator, a device he’d invented to help pilots measure how fast their aircraft were banking. His engineering mind immediately grasped the connection. If a gyroscope could determine how fast an aircraft was turning, it could also predict where that aircraft would be in the future.

What if we could make the gun’s sight automatically lead the target? He asked quietly. The concept seemed impossible. A mechanical device that could think ahead, calculating where to aim based on current movement. But Draper saw the mathematical elegance. His gyroscope didn’t need to be intelligent. It just needed to be precise. The revolutionary insight.

Draper’s breakthrough was understanding that he didn’t need to replace human judgment with mechanical computation. He needed to augment human reflexes with gyroscopic precision. The gunner would still track the target and pull the trigger, but the site would automatically adjust the aiming point to compensate for the target’s movement.

By September 1940, he’d worked out the theory. The device would use a small gyroscope to measure how fast the gunner tracked a moving target, then automatically offset the sight’s aiming point to provide the correct lead angle. The idea was so simple that trained engineers had overlooked it, yet so revolutionary it would transform aerial warfare.

Working evenings and weekends in his MIT basement laboratory, Draper built a crude prototype, a shoe box-sized metal box containing a silver dollarsized gyroscope spinning at 24,000 revolutions per minute, connected to an optical system that projected an illuminated aiming point. He mounted it on a 22 caliber rifle and spent hours testing it against the towel, swinging back and forth like a pendulum.

By midnight, he was hitting the moving target consistently, something nearly impossible with conventional sights. The breakthrough came with his final shot when the towel swung at an angle, simulating an aircraft in a banking turn. Draper tracked smoothly, let his gyroscopic sight calculate the lead, and squeezed the trigger.

The bullet tore through the center of the moving towel, breaking through skepticism. When Draper presented his invention to military representatives, the response was immediate and hostile. “This is completely insane,” declared a Navy ordinance officer. “You want to put a spinning top on a gun and expect it to hit flying targets? That’s impossible.

” The room erupted in dismissive laughter. But Draper had seen his invention work. In May 1941, Lieutenant Commander Marian Murphy arranged a crucial meeting with Captain William Blandy, chief of the Bureau of Ordinances Research and Development Division. 12 senior officers and civilian engineers assembled to evaluate Draper’s prototype.

The crude metal box drew skeptical stairs. Experts immediately raised objections. Lead calculations required massive mechanical calculators. The system was fundamentally flawed. It relied on human skill rather than eliminating human error. Would you like to see a demonstration? Draper asked simply. Two days later at the Watertown Arsenal firing range, Draper fired at targets moving at varying speeds and angles. Hit after perfect hit.

By the fifth consecutive success, skepticism transformed into amazement. Captain Blandy made the decision that would change naval warfare. I want specifications and pricing for 50 experimental units. Combat transformation by January 1943. Comprehensive testing at the Naval Proving Ground in Virginia produced stunning results.

Conventional iron sights 3.2% success rate. Mark1 14 gyroscopic sights 10.1% success rate more than triple the kill rate individual gunners improved rapidly because automatic lead calculation let them focus on smooth tracking rather than mental mathematics with the old sights I was always guessing reported one gunner with the Mark1 14 I just keep the target in the sight and squeeze the trigger the first combat test came during the November 1943 invasion of the Gilbert Islands.

As Japanese Betty bombers dove toward the USS Lexington at 350 mph, gunners using Mark14 sights opened fire. Within 15 minutes, American ships shot down 11 Japanese aircraft while suffering only minor damage, a complete reversal of previous engagements. But the most dramatic proof came during the kamicazi attacks on the Philippines in October 1944.

Tommy Rodriguez, the gunner from our opening scene, now operated a gun equipped with Draper’s sight. As kamicazi’s dove at 400 mph, Rodriguez tracked the lead aircraft through his Mark1 14. The gyroscopic mechanism automatically calculated the lead angle. His shells intercepted the diving plane at 2,000 yards, destroying it before it could reach the carrier.

The Philippine campaign statistics were staggering of 1,947 kamicazi aircraft engaged ships with Mach 14 sights shot down, 1452, a 78.6% success rate. Enemy recognition and legacy. Intercepted Japanese communications revealed growing alarm. American defensive fire has become devastatingly accurate, reported one commander.

It is as if their gunners can see into the future. Admiral Takajiro Onishi was blunt. American ships have become nearly impossible to attack. We must assume that every approach to enemy vessels will result in our aircraft’s destruction. By wars end, 85,000 Mark14 sites equipped American and British guns.

The device had destroyed 23,147 enemy aircraft and saved an estimated 50,000 American lives. Ships with Mark 14 sights achieved kill rates 15 times higher than those with conventional gunnery. When reporters approached Draper after the war, he consistently deflected credit. I just solved a mathematics problem, he insisted. The real heroes are the young men who use those sites to defend their ships.

He refused commercial endorsements and celebrity appearances, returning to his MIT laboratory to focus on new challenges. His wartime innovations became the foundation for modern inertial navigation systems and missile guidance. His work led directly to the Apollo program’s navigation computers.

Today, every American submarine carries missiles guided by systems descended from Draper’s innovations. Dr. Charles Stark Draper succeeded where established experts failed because his unconventional background allowed him to see solutions others missed. As one MIT colleague observed, Doc didn’t know that automatic lead calculation was impossible.

So he went ahead and invented it anyway. The man who revolutionized aerial warfare asked for no recognition, claimed no glory, and sought no profit. His legacy lives in every precision weapon system and every serviceman who came home alive because one MIT professor refused to accept that hitting moving targets was impossible.