Saipan, June 17th, 1944. 600 hours. Lieutenant Colonel Tekashi Kurasawa stands in his command bunker, 800 yd from the nearest American position. The morning air is still, humid, heavy with the smell of coral dust and yesterday’s smoke. He raises his field glasses, studies the marine lines.

The Americans are digging in, fortifying, preparing for the push inland. Captain Nakamura stands 3 ft to his left. Younger officer, 31 years old, graduate of the Imperial Army Academy. Promising career ahead. Nakamura is speaking. Something about repositioning the machine gun positions on the eastern flank. The morning air cracks.

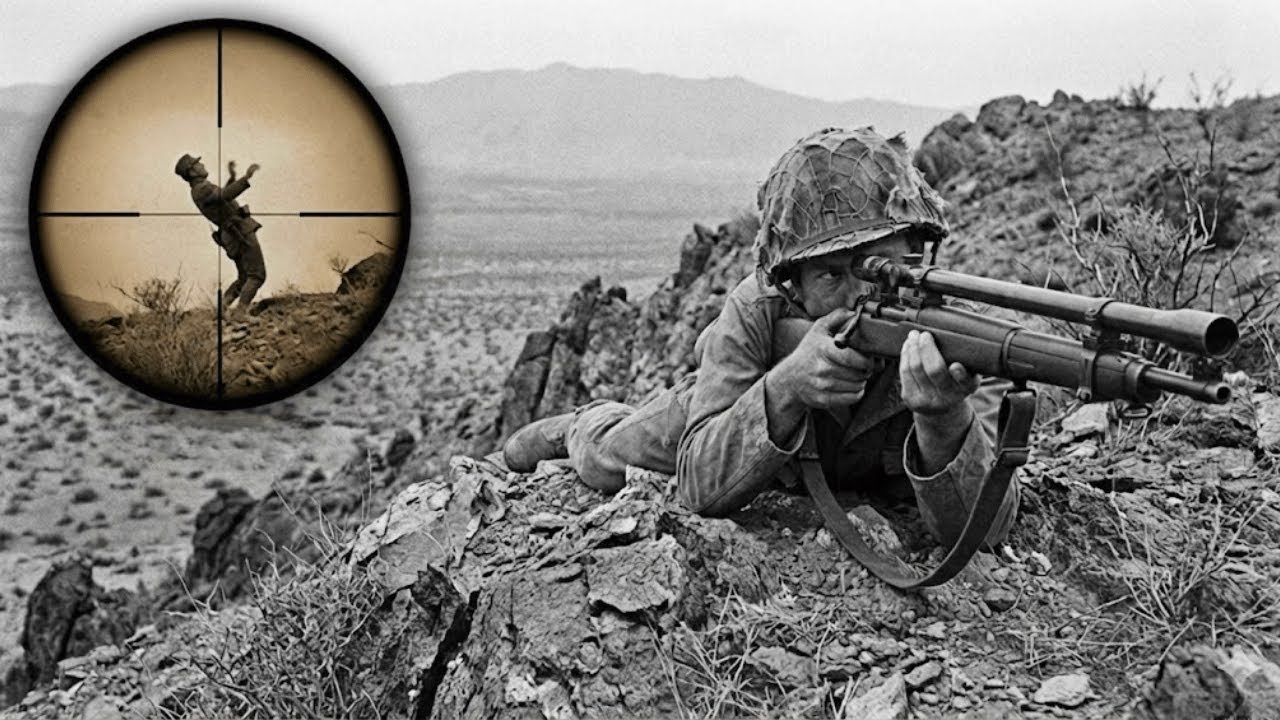

A single rifle shot. Sharp, distant, almost lost in the ambient noise of war. Nakamura stops mid-sentence. His head snaps backward. A perfectly centered hole appears in his forehead. Clean, surgical. The back of his skull erupts in a spray of red mist that spatters across the coral wall behind him. He drops.

Kurasawa throws himself to the bunker floor. Rough coral scrapes his face. His staff officers scramble for cover, shouting confusion, but Kurasawa isn’t listening to them. He’s calculating. No muzzle flash visible anywhere along the American lines. No telltale smoke. No movement, nothing that would indicate where death had just come from.

The Americans are 800 yardds away. 800 yardds. Impossible shooting range for infantry weapons. Kurasawa presses himself against the coral. His heart hammering. And for the first time in 20 years of military service, he feels something he hasn’t felt since his first combat in China. Fear. Not of death. Fear of an enemy he cannot see, cannot hear, cannot fight.

Death from nowhere. 1,100 yards away. Corporal EMTT Lancaster Holloway lowers his rifle. 22 years old, West Texas, Amarillo, born and raised. The Unertle’s eight power lens reveals the Japanese bunker in crystalline detail. The chaos. Officers diving for cover. The perfect stillness of the man he just killed. His spotter, Corpal Davies, adjusts his binoculars. Clean kill, Holay.

He never knew. Holay doesn’t respond immediately. He’s counting in his head. 68. 67 before today. And now this one. That’s number 68. He’s been keeping count since Guadal Canal. Doesn’t know why he started. Doesn’t know when he’ll stop. 68 men. 68 times he’s looked through this scope and calculated trajectory and wind drift and bullet drop and squeezed a trigger and watched a man fall at distances most soldiers can’t even see 68 faces because the unertal 8 power scope shows faces even at 800 yd even at a thousand distance collapses through the lens it

shows faces and expressions and that last moment when a human being realizes something is wrong but doesn’t yet know They’re already dead. “Confirmed kill,” Davey says again, waiting for response. “Confirmed,” Holay finally answers, his voice flat, emotionless. He pulls back from the rifle, begins the ritual.

Clean the barrel, check the scope mount. Record the shot in his notebook. Range: 1,100 yd. Wind 6 mph left to right. Temperature 84° Fahrenheit. Target: Japanese officer, captain, or major rank, coordinating defensive positions. Result: immediate incapacitation. Kill number 68. He closes the notebook and somewhere in the back of his mind, a voice that sounds like his father asks a question he’s been avoiding for 2 years.

When did you stop being a boy who loved shooting and become a man who counts dead bodies? Amarillo, Texas. Summer 1938. 6 years earlier. Emmett Holloway is 16 years old. Skinny kid, all elbows and knees. Hair the color of West Texas dust. He’s standing on a firing line at the Amarillo Rod and Gun Club.

West Texas Junior Shooting Championship 1,000yard competition. Most boys his age are using their father’s hunting rifles. 30 caliber deer guns. iron sights good enough to hit a barn at 500 yd if you’re lucky. EMTT is using his father’s Winchester Model 70. It has a scope, four power, nothing special, but in EMTT’s hands, it might as well be a surgical instrument.

The target is a thousand yard down range. That’s over half a mile. At that distance, a man is barely visible to the naked eye, a small dark shape against lighter earth. The wind is gusting 8 to 12 mph. Variable, unpredictable. EMTT settles into position, breathing controlled, heart rate slow. He looks through the scope.

The target swims into view. A black circle on white paper. At this distance, it looks like a pin prick, but EMTT doesn’t see it the way other shooters do. He sees mathematics. Wind velocity creates drift. Calculate based on bullet weight and ballistic coefficient at this range. Maybe 18 in left. Bullet drop at 1,000 yards with this load is approximately 24 ft.

Aim high. Way high. Temperature affects powder burn rate. Hot day means faster velocity. Adjust down 2 minutes of angle. He doesn’t think these calculations consciously. His brain does them automatically. the way other people breathe without thinking about breathing. His father watches from behind.

Doesn’t understand how his son does this. EMTT never took a ballistics course, never studied engineering. He just knows. EMTT squeezes the trigger. The Winchester barks. Downrange 1,000 yd away. The target shows a new hole. Dead center. He fires four more times. Four more holes. All within a 6-in circle. Perfect score.

The range officer, an old man named Henderson who fought in the First World War, walks over after the scores are posted. He looks at EMTT with something between respect and concern. Son, Henderson says, you got a gift. Eyes like a hawk, hands like a surgeon. But that’s not what makes you special, Emtt waits.

What makes you special is you see distance differently than normal folks. You see math where we see empty space. EMTT’s father nods. He’s heard this before from teachers, from other shooters. My boy don’t see the world like other people. That’s true. His father says he sees angles and distances and probabilities. Always has.

Henderson looks at EMTT seriously. That’s a rare gift, son. You could go far with that. Maybe competitive shooting. Maybe Olympic team someday. He pauses. Or maybe the military. They’re always looking for boys who can shoot. especially boys who can shoot at distances that seem impossible. EMTT is 16.

He doesn’t think about the military, doesn’t think about war. He just likes the mathematics of longrange shooting, the precision, the challenge of hitting a target most people can’t even see. But four years later, when the Japanese bomb Pearl Harbor, Henderson’s words will come back to him, and EMTT Holloway will discover that the mathematics of shooting targets and the mathematics of shooting men are exactly the same.

The emotional cost is the only difference. Guadal Canal, August 1942. Private First Class EMTT Holloway steps off the landing craft into kneedeep water. He’s 20 years old now, 4 years older than that skinny kid on the Texas firing line. But he still looks young, babyfaced, 165 lb soaking wet.

The M1 Garand rifle he’s issued weighs 9 and 12 lb. Standard infantry weapon, semi-automatic, eight round clip. Good rifle, but EMTT hates it. iron sights, no magnification. Effective range may be 300 yards on a good day with perfect conditions. For a boy who spent his childhood hitting targets at a thousand yards, the M1 Garand feels like fighting with one hand tied behind his back.

He says as much to his squad leader after three days of patrols. The sergeant, a veteran of the pre-war Marine Corps, just laughs. Kid, you ain’t here to win shooting competitions. You’re here to kill Japanese. The Garand kills Japanese just fine at 200 y. That’s close enough, but it’s not close enough for EMTT because at 200 y faces, you see eyes.

You see the moment a human being realizes they’re about to die. EMTT wants distance, wants separation, wants the mathematics to insulate him from the humanity. So when he sees a notice posted at battalion headquarters, scouts sniper school accepting applications, preference given to competitive shooters, he volunteers immediately.

The selection course is brutal. 200 Marines apply. 20 are selected. EMTT is one of them. And that’s how he meets Master Gunnery Sergeant Augustus Pierce. Pierce is 38 years old, Montana, lean as a fence post, face carved from granite. He’s been shooting competitively since he was 16.

Won the Camp Perry national matches in 1935, again in 1937, again in 1939. Camp Perry, the pinnacle of American long range rifle competition, where the best shooters in the country gather every summer to shoot at targets 600, 800, 1,000 yards away. Pierce has forgotten more about long range precision shooting than most Marines will ever know.

He looks at the 20 candidates assembled for Scout Sniper School. “Most of you won’t make it through this course,” he says. No preamble, no welcome speech. Not because you can’t shoot, but because you can’t think. He picks up a rifle from the table behind him. This is an M1903A1 Springfield boltaction, five rounds, built on the same action your grandfathers used in the First World War. He mounts a scope to the rifle.

The scope is massive, nearly as long as the barrel itself. This is an Unertle 8 power scope made by John Unertle in Pittsburgh. Cost $4,400. That’s more than most of you make in 6 months. The candidates stare at the scope. It looks like something you’d use to study stars, not kill men. Pierce continues.

This scope has external target knobs. See these? He points to two cylindrical knobs mounted on top and on the side of the scope. Windage and elevation. Each click moves your point of impact one quarter minute of angle. Some of the candidates look confused. Pierce doesn’t slow down. 1 minute of angle at 100 yd equals approximately 1 in.

At 1,000 y, 1 minute of angle equals approximately 10 in. So each click on these knobs moves your bullet impact about 2 1/2 in at 1,000 y. He looks at the group. This scope also has eight power magnification. You know what eight power means? Silence means a target at 800 yd looks like it’s at 100 yard. Means you can see faces, see details, see things that iron sights at 200 y can’t show you.

He pauses, lets that sink in. This rifle and this scope together cost $2,400. That’s what the military pays. The Japanese type 97 sniper rifle costs about $400. Their scopes are 2.5 power magnification. Ours is eight power. Another pause. We have better equipment, better training, better institutional knowledge. You know why? No one answers.

Pierce continues anyway. Because Americans have been shooting thousandy competitions for 40 years. Marines dominated Camp Perry since 1907. We developed this equipment for sport, for fun, for weekend competitions where grown men shoot at paper targets from distances most soldiers never even think about.

He holds up the rifle with the unertal scope mounted. The Japanese military doesn’t know this equipment exists. They don’t have civilian shooting sports, no Camp Perry in Tokyo, no thousand-y competitions, no culture of long range precision as recreation. He looks at each candidate individually. That ignorance is their weakness. Our knowledge is our strength.

And you are going to exploit that gap until this war is over or you’re dead. Then he looks directly at EMTT. Holloway, step forward. EMTT does. Pierce hands him the rifle. I read your application. West Texas Junior Champion. Perfect score at 1,000 yards. Age 16. Yes, gunnery sergeant. You ever shot through a scope this powerful? No, gunnery sergeant.

Highest magnification I used was four power. Pierce nods. Look through it. Tell me what you see. EMTT shoulders the rifle, looks through the unertal scope at a target set up 800 yd down range. The target leaps into view, crystal clear, almost shockingly detailed, like someone moved it 700 yd closer. Holy. Emmett catches himself.

That’s incredible gunnery sergeant. That’s technology. Pierce corrects. German Zeiss quality glass. American precision manufacturing. 40 years of competitive shooting knowledge built into one instrument. He takes the rifle back. This scope will let you kill men at ranges they think are safe.

Will let you see their faces before you end their lives. will show you every detail of what happens when a 30 caliber bullet traveling 2800 ft pers hits a human skull. Pierce’s voice drops lower. Serious. This ain’t your daddy’s deer rifle anymore, Holay. This ain’t shooting paper targets in Texas. This is applying mathematics to human beings.

He looks at all the candidates again. You’re going to learn ballistics, wind reading, range estimation, atmospheric effects, trajectory calculation, how temperature and humidity and barometric pressure affect bullet flight. You’re going to learn how to see a man at 800 yd, and calculate exactly where to aim so that the bullet falls through 24 ft of arc and drifts 18 in sideways in the wind and still hits him center mass.

You’re going to learn how to kill efficiently, precisely, without emotion. Then he says something that will stay with EMTT for the rest of his life. But here’s what they don’t teach in ballistics class. Here’s what no book can prepare you for. Pierce’s voice is quiet now. Almost gentle. You’re going to see the man before you kill him.

Eight power magnification shows faces, shows fear, shows the moment they realize something’s wrong, shows them falling, shows them dying. And you can’t unsee that ever. So before you continue with this training, I need you to understand something. Becoming a sniper isn’t about being a good shot. Any competent rifleman can be trained to hit targets at range.

Becoming a sniper is about being able to see a man’s face magnified eight times and still complete the calculation. Calculate the trajectory, adjust for wind, squeeze the trigger, watch him fall, and then do it again and again and again until the war is over or you are. Pierce looks at each man individually one final time.

Anyone who wants to quit, walk away now. No shame in it. Infantry needs good riflemen. No one moves. Not yet. They will later as the training progresses, as the reality sinks in, as they begin to understand what Pierce means about seeing faces. But right now, 20 young Marines stand in formation, believing they understand what they’re signing up for.

Only one of them, Emtt Holloway from Amarillo, Texas, will eventually accumulate 87 confirmed kills with that unertal scope. Only one will learn that perfect vision is both a gift and a curse. Only one will spend the next 60 years remembering 87 faces seen through 8 power magnification. But on this day in August 1942, EMTT Holay is just a 20-year-old kid who likes mathematics and precision shooting.

He doesn’t yet know that in 3 months he’ll look through that unertal scope at a Japanese officer named Lieutenant Ishida. He’ll calculate wind drift and bullet drop and atmospheric effects. He’ll squeeze the trigger and he’ll watch magnified to intimacy as that bullet arrives two seconds before the sound of the shot. He’ll see the impact, see the fall, see the death, and he’ll learn exactly what Master Gunnery Sergeant Augustus Pierce meant about seeing too much.

That lesson is coming soon. Terawa atal, November 20th, 1943. Dawn. Sergeant Emmett Holloway stands on the deck of the USS Ashland. 21 years old now, 15 months since Guadal Canal. 23 confirmed kills in his notebook. 23 faces he sees when he closes his eyes at night. The invasion fleet surrounds him. Dozens of ships.

Hundreds of landing craft preparing to hit the beaches. Thousands of Marines checking weapons, writing last letters home, making peace with whatever god they believe in. Master gunnery Sergeant Pierce stands beside him, studying the island through binoculars. Bashio Island, tiny strip of coral, barely 3 mi long, half mile wide, but fortified like no other island in the Pacific.

Concrete bunkers, reinforced pillboxes. 4,500 Japanese defenders who’ve spent a year preparing for this moment. Rear Admiral Shibasaki, the Japanese commander, has publicly boasted that a million Americans couldn’t take Betio in a 100 years. Pierce lowers his binoculars. Holloway, you see that command bunker northern end of the airfield? EMTT looks through his unertal scope mounted on his M1903A1.

The eight power lens brings the bunker into sharp focus 1,320 yd away across open water. I see it, Gunny. Admiral Shibasaki coordinates the defense from there. Intelligence confirmed it yesterday. Kill him. The defense loses coordination. Maybe saves 500 Marine lives. Maybe more. EMTT studies the distance, the conditions.

1320 yd. That’s 3/4 of a mile. Longer than any shot he’s taken in combat. Longer than most shots anyone has taken in combat. And it’s across water. Wind coming off the ocean. Variable. Unpredictable. Temperature gradient between the 84° water and 92° land. Heat shimmer. Mirage. Refraction. The mathematics are at the edge of possible.

Gunny. That’s extreme range. I know. But you’re the best eye in the division. If anyone can make this shot, it’s you. The first wave of landing craft hits the reef, 800 yards from shore, too far out. They’re supposed to float over the reef. But the tide is wrong. The Higgins boats ground out.

Marines pour over the sides into chest deep water. Japanese machine guns open up. The water turns red. Men fall. Dozens, hundreds, screaming, drowning, dying in water so shallow they could stand if they weren’t torn apart by bullets. Pierce’s jaw tightens. Take the shot, Sergeant. EMTT settles into position. The M1903A1 rests on sandbags. Stable platform.

He controls his breathing, slows his heart rate. The Unertle reveals Shibasaki in perfect clarity. Movement. Older man, naval uniform, studying the beach through binoculars. Admiral Shibasaki. EMTT begins the calculation. Range 1,320 yd. At this distance, the bullet will drop 67 in. That’s over 5 ft. Aim high.

Wind 8 mph. Variable coming off the ocean left to right. At this range, maybe 18 in of drift. Adjust right. Temperature 84° at water level, 92° at land. Heat gradient creates mirage. The bullet will rise slightly through warmer air. Compensate down. Corololis effect. At extreme range in the northern hemisphere, the rotation of the earth deflects bullets slightly right.

At 1320 yd approximately 2 in adjust left. bullet drop, wind drift, temperature, coriolis, mirage, atmospheric pressure, all of it running through his head simultaneously. Automatic calculation. The same way he calculated shots at paper targets in Texas when he was 16. But this isn’t a paper target. At this magnification, EMTT can see Admiral Shibasaki’s face.

Can see him pointing, giving orders, coordinating the slaughter happening on the reef. 47 clicks elevation, 12 clicks windage. EMTT makes the adjustments. The external target knobs on the unertal scope click precisely. Each click moving the point of impact exactly one4 minute of angle. He settles the crosshairs. Not on Shibasaki.

On a point in empty air 5 ft above and 18 in to the right of where Shibasaki stands. That’s where the bullet will be 1 second after leaving the barrel. 67 in of drop, 18 in of drift. Physics doesn’t lie. EMTT breathes out slowly, half breath, hold, squeezes the trigger. The Springfield recoils. The unertal scope slides backward in its mount, returns to battery. The scope shows him everything.

The bullet is invisible, but he knows its path, knows the ark, knows the trajectory. 1 second, the bullet climbs, reaches apex 400 yd downrange. 2 seconds. Descending now, falling through the arc he calculated. 3 seconds. 3.2 seconds. Admiral Shibasaki jerks backward. The binoculars fly from his hands. He collapses.

Pierce watching through his spotting scope confirms. Hit center mass. He’s down. On Betio Island, chaos erupts in the command bunker. Officers rushing. Confusion. The defense coordination collapses. Without Shibasaki’s leadership, the Japanese response becomes disjointed, uncoordinated. Individual strong points fighting alone instead of mutually supporting. The Marines push inland.

Casualties are still horrific, but not as bad as they would have been. Pierce was right. That one shot probably saved 500 lives. But EMTT isn’t thinking about 500 saved lives. He’s thinking about 3.2 seconds. 3.2 seconds of watching his bullet fly. Watching the target magnified to intimacy. Watching the impact. Watching the fall.

Watching a human being transition from alive to dead. Most rifle shots you never know if you hit. The target is too far, too obscured. You shoot, you displace, you move on. But at 1320 yd with eight power magnification on a stable platform, watching across open water, Emmett saw everything. Saw the bullet impact. saw Shibasaki’s body react, saw him fall, saw the death. For 3.

2 seconds, he was a witness to his own killing. That night, after the fighting, after Bashio is secured at the cost of over a thousand marine dead and 2,000 wounded, EMTT leans over the ship’s rail and vomits into the Pacific. Pierce finds him there. What’s wrong, Sergeant? That was a perfect shot. Textbook. One of the longest confirmed kills in Marine Corps history. EMTT wipes his mouth.

I watched him die. Gunny. Yeah, that’s the job. No, I mean I watched for 3 seconds. I watched my bullet travel. Saw it hit. Saw him fall. That’s different than not knowing. Pierce is quiet for a moment. The magnification. The magnification. EMTT confirms. Eight power shows everything. At that range, with that much time of flight, I wasn’t just shooting.

I was watching someone die that I killed. Pierce lights a cigarette, offers one to Emmett. EMTT doesn’t smoke, but takes it anyway. How many now? Pierce asks. 24. You remember all of them? Every face. Pierce exhales smoke. Physics justified it today, Holay. Calculus proved it. That’s the equation. One Japanese admiral for 500 American lives.

I know the numbers, Gunny. The numbers are perfect. EMTT looks out at the dark water. It’s the seeing that’s killing me. Saipan, June 1944. Staff Sergeant Emtt Holloway leads Scout Sniper Platoon Charlie. 22 years old. 67 confirmed kills before this morning. 68 now, counting Captain Nakamura from the cold opening. The platoon’s mission has evolved.

No longer just eliminating targets of opportunity. Now it’s systematic psychological warfare. Decapitate the Japanese command structure. Force officers underground. Make them afraid to coordinate. Afraid to observe. Afraid to lead. Turn their leadership into liability. It’s effective. Captain Hideo Ober commands a resistance force in the northern hills.

His men are dug into caves supposedly safe, beyond the range of American artillery, beyond the reach of American infantry, but not beyond the reach of Emmed Holloway’s Unertle scope. Ober keeps a journal hidden in his cave, he writes entries by candle light. June 23rd, lost Lieutenant Sasaki today, shot from impossible distance.

Men say the ghost shooters can kill from beyond the clouds. Some believe Americans have death rays, invisible weapons. I tell them these are superstitions, but I don’t know what else to call an enemy we cannot see, cannot hear, cannot fight. June 25th. Sergeant Yamada refused to leave the cave today, even when ordered.

He says the Americans can see through walls, can shoot around corners. Madness. But three more men dead today from invisible fire. How do I maintain discipline when the men fear an enemy that seems supernatural? July 1st. We captured an American rifle last night. The scope is terrifying. 8 times magnification.

I looked through it. Could see individual Marines from distances I thought safe. Could read expressions on their faces and the adjustments, precise mechanical adjustments for wind and range. We have nothing like this. Nothing even close. Colonel Tadashi Suzuki examines the captured M1903A1 in his intelligence bunker.

He’s 39 years old, career intelligence officer, studied at military academy, served in China, Manuria, Philippines. He thought he understood American military capability. He was wrong. Suzuki looks through the Unertle scope, points it at a ridgeel line 800 yd away. Distance collapses through the lens. He can see individual American soldiers, see their faces, see them moving, talking, living, all of them visible, all of them vulnerable.

He examines the external target knobs, turns them carefully, hears the precise clicks, reads the markings. Quarterminute adjustments. He calls Tokyo, speaks to Imperial Army headquarters. We are fighting blind against an enemy who can see, he tells them. request immediate production of equivalent optical systems. The response comes back three days later.

Japanese optical engineers have examined the specifications. They report precision grinding equipment required does not exist in Japanese factories. Optical glass quality exceeds current manufacturing capability. Skilled workforce for instrument grade assembly not available. Estimated time to develop production capacity 18 months minimum.

The war will be over by then. Suzuki realizes the truth. Even knowing the technology exists, even having an example to copy, Japan cannot replicate it. The industrial capacity gap, the skilled labor gap, the institutional knowledge gap. 40 years of American civilian marksmanship tradition created infrastructure and expertise Japan never developed.

And now when they need it most, they cannot close that gap fast enough. Suzuki writes in his report, “We are not losing because our soldiers lack courage. We are losing because American soldiers can see 800 yards and we can see 300. No amount of Bushidto spirit overcomes that advantage.” The report is filed, classified, never acted upon.

Japanese officers continue dying at impossible ranges, and men like Emtt Holloway continue pulling triggers. Pelu, September 1944. Gunnery Sergeant Emtt Holloway, 22 years old, 79 confirmed kills. Colonel Kunio Nakagawa commands the Japanese defense. Brilliant tactician. Studied every previous American invasion.

learned from every defeat. He implements counter measures. No officers visible in daylight. All movement through covered trenches. No gatherings larger than three men. Dummy officers as decoys. Constant deception. If the Americans need to see to kill, Nakagawa tells his staff. We become invisible. It works partially.

American sniper effectiveness drops. Fewer officer casualties. The Japanese defense is coordinated, organized, deadly. But EMTT adapts. He doesn’t hunt visible officers anymore. He watches, observes, studies behavior magnified to intimacy. Japanese soldiers defer to certain individuals. Subtle body language. A private stepping aside to let someone pass.

A corporal waiting for another corporal to speak first. Small indicators of rank and authority. Eight power magnification shows these details. EMTT identifies leaders by how other men treat them. No insignia required. It takes longer, requires patience, days of observation. Sometimes, but it works. Day six of the Pelu campaign.

EMTT observes a Japanese position 780 yard distant. The Unertle reveals his target in perfect detail. A man giving quiet directions to others. They listen, defer, obey. officer. No visible rank, but definitely leadership. EMTT settles into position. Stable, breathing controlled, heart rate slow. He’s done this 79 times before. He calculates wind, range, temperature, bullet drop, ballistics doesn’t lie.

He begins the trigger squeeze. Smooth, steady, inexurable. The trigger breaks. In that fraction of a second between trigger break and bullet impact, a young Japanese soldier steps into the sight picture. 18 years old, maybe younger, thin, carrying a water canteen to the position. The bullet strikes him center mass.

Eight times magnification, collapses distance into intimacy. The impact, the fall, body hitting ground, the writhing that follows. Every detail crystalline, unavoidable, permanent. sees the boy land on his back. Not instant death, wounded, suffering. The boy is calling out. EMTT can’t hear the words, but can see his mouth moving, calling for help.

The officer EMTT intended to kill runs to help, kneels beside the wounded boy, exposes himself completely. EMTT has a clear shot. Easy shot. 780 y. The officer he intended to kill in the first place. His finger rests on the trigger. He watches. The officer is trying to stop the bleeding. The boy is dying slowly.

Emmett doesn’t take the shot. He watches them carry the wounded boy away. Watches them disappear into the fortifications. Sergeant Davies, his spotter, looks confused. Holloway, you had him. Target moved, EMTT says, flat, emotionless. It’s a lie. The target was stationary for 15 seconds. Perfect shot. Impossible to miss.

But EMTT couldn’t take it because magnified to intimacy, he’d watched a boy, maybe 18, maybe younger, die from a bullet that wasn’t meant for him. Watched him suffer, watched him call for help, watched the fear in his eyes. And for the first time in 79 kills, EMTT Holloway couldn’t complete the calculation. That night, he makes an entry in his notebook. Kill number 80.

Age approximately 18. Target. Collateral casualty. Center mass hit. Death not immediate. Suffered approximately 90 seconds before loss of consciousness. Then he writes something he’s never written before. This one I’ll remember differently than the others. He closes the notebook. Somewhere in the Japanese fortifications, that boy is probably dead by now.

The wound was lethal, just slow, and an officer survived because Emtt Holloway saw too much magnified to intimacy and couldn’t calculate death while watching suffering. Master Gunnery Sergeant Pierce would say, “That’s a failure. Mission failure. Let emotion override objective.” But Emmett doesn’t care what Pierce would say because he’s alone with 80 faces in his memory.

81 counting today. Some killed instantly, clean, efficient, mathematical. One killed slowly, accidentally, while Emmett watched magnified eight times and learned that not all killing is equal. Some deaths are quick. Some deaths take 90 seconds. And when you’re watching at this magnification at 780 y, 90 seconds is an eternity.

By the end of Pelu, Colonel Nakagawa has lost 43% of his company grade officers despite all counter measures. American snipers have adapted to every defensive measure, learned every trick, overcome every obstacle. Sergeant Harada, one of the few Japanese snipers to survive the campaign, writes in his report, “American snipers operate at ranges where our Type 97 rifles cannot even identify targets clearly.

We attempt to locate their positions by sound, but the bullet arrives before the sound of the shot. We are fighting modern rifles with equipment that might as well be matchlocks. I recommend we abandon counter sniper operations as wasteful. The technology gap cannot be overcome with available resources. The report goes to Nakagawa.

Nakagawa forwards it to higher command. It’s filed and forgotten. November 1944, Pearl Harbor, replacement depot. Master gunnery sergeant Augustus Pierce is rotating stateside. Back to Camp Pendleton. Training assignment. He finds EMTT before shipping out. Holay Gunny. They stand awkward. Two men who’ve worked together for 2 years.

Shared kills, shared burdens. Don’t know how to say goodbye. Pierce speaks first. You’re the best natural shooter I ever trained. Thank you, Gunny. That’s not a compliment. That’s a warning. EMTT waits. The better you see, the more you’ll remember. Eight power magnification is a gift and a curse. You got the gift. You’ll carry the curse.

I’m already carrying it. Pierce nods. I know. I see it in your eyes. That thousand yard stare, not from distance, from seeing too much too clearly. He puts a hand on EMTT’s shoulder. The war will end. You’ll go home. You’ll have a life. But those faces will stay with you. All of them. Perfect clarity forever.

How do you deal with it? You don’t deal with it. You carry it like we carry the rifle. It’s the weight of the job. Pierce’s transport is boarding. One more thing, Holay. When you get home, don’t just count the kills. Count what you saw that saved others. The intelligence reports, the observations. That matters, too. How many did you kill, Gunny, in all your years? Pierce is quiet. 43.

43 faces I still see. Does it get easier? No. You just get better at carrying it. Pierce boards his transport. Holay never sees him again. But Pierce’s words stay with him. Count what you saw that saved others. 40 years later, when declassified reports reveal 147 intelligence reports filed, Holay will finally understand what Pierce meant.

The seeing mattered more than the shooting. Always had. Okinawa, April 12th, 1945. Dawn. Gunnery Sergeant Emmett Holloway crouches in a destroyed building overlooking the Shury line. 23 years old, 87 confirmed kills. He hasn’t fired his rifle in 3 weeks. Not because there aren’t targets. There are plenty. Japanese forces dug into the most sophisticated defensive network in the Pacific.

Tunnels, bunkers, interconnected positions that have consumed marine battalions like a meat grinder. EMTT hasn’t fired because he’s been promoted. Senior sniper adviser plans operations, coordinates teams, trains replacements. He rarely shoots anymore. But today is different. Today requires the best eye in the division. Colonel Hirami Yahara commands Japanese defensive operations.

Brilliant strategist designed the Shuri line. The man who turned Okinawa into a killing field. Intelligence reports he coordinates from a command post on the reverse slope. Hidden, protected, beyond the reach of artillery, but not beyond the reach of a precision rifle. EMTT studies the position. 940 yards. Difficult shot. Not impossible.

His scope reveals movement in crystalline detail. Japanese soldiers, officers coordinating, planning, and then he sees something else. Civilians. Okinawan civilians. Families hiding in the ruins near the Japanese position. Old men, women, children. They’re 15 ft behind where the Japanese artillery spotter stands.

The spotter calling fire on Marine positions, killing Americans with every radio transmission. Standard procedure is clear. Eliminate the spotter. Stop the artillery. But EMTT can see what others can’t see with the naked eye. The civilians are directly behind the target. The 30 caliber round from his M1903A1 will punch through a human body at this range. Through and through.

Over penetration likely. High probability of hitting civilians beyond the target. He lowers the rifle. His spotter, Corporal Williams, looks confused. Sergeant, you have the shot. Civilians in the background, 15 ft behind target. Round will overpenetrate. Williams looks through his spotting scope.

At 940 yards, with his lower magnification, he can barely see the civilians. How can you tell they’re civilians? 8 power magnification. I can see them clearly. Old woman, two children, maybe 8 and 10 years old. Williams is quiet for a moment. Orders are to eliminate the spotter. He’s killing Marines. I know the orders. EMTT settles back into position, watches, calculates.

One Japanese spotter, four Okinawan civilians, unknown number of marine casualties while he waits. The mathematics are no longer simple. Master gunnery Sergeant Pierce trained him that war is mathematics. Calculate trajectories, eliminate variables, complete the mission. But Pierce isn’t here, and EMTT is looking at two children magnified eight times while listening to American artillery falling on Marine positions because he won’t take a shot that might kill them.

He waits. Minutes pass. The Japanese spotter continues calling fire. EMTT can hear the radio transmissions faintly. Can’t understand the words, but knows what they mean. More Marines dying. 10 minutes. Williams shifts uncomfortably. Sergeant, I’m waiting for a clear shot. 20 minutes. The artillery intensifies.

A marine position takes a direct hit. EMTT can hear the explosion even from here. Can imagine the casualties. 30 minutes. 40. 47 minutes after first acquiring the target. The Japanese spotter moves, steps forward, adjusts his position to get better view of the marine lines. Clear lane. No civilians in background.

EMTT doesn’t hesitate now. The calculation is instant. Wind, range, temperature, bullet drop. He fires. 940 yd. The spotter drops. Immediate incapacitation. The Japanese artillery falls silent. No spotter to direct fire. Williams confirms through his scope. Target down. Clean kill. EMTT pulls back from the rifle.

Records the shot in his notebook. Kill number 87. Range 940 yards. Japanese artillery spotter. Waited 47 minutes for clear shot to avoid civilian casualties. Target eliminated. Artillery suppressed. Then he adds a line he’s never written before. Two Marines KIA during weight. Four Okinawan civilians survived. Did I calculate correctly? He doesn’t know the answer. We’ll never know.

The statistics tell one story. Marine Corps Scout Sniper Operations Pacific Theater 1942 to 1945. Total Scout Snipers deployed approximately 400 less than 1% of total Marine forces. Japanese officer casualties attributed to sniper fire over 15%. Gunnery Sergeant Emmett L. Holloway. Individual record 87 confirmed kills zero wounded.

All kills immediate incapacitation. Average engagement range 820 yards. Longest confirmed kill 1320 yd. Success rate 94%. 87 kills from 92 shots fired. But statistics don’t tell the whole story. The physical cost. EMTT weighs 138 lb, down from 165 when he deployed. 27 lb lost over 3 years. His right eye shows permanent strain damage from scope use, partial vision degradation, what the doctors call scope eye.

His hands shake, not constantly, but sometimes, cold exposure damage, stress, fatigue. His right shoulder is one massive bruise. 3,000 rounds fired through an M1903A1 Springfield over 3 years. The recoil accumulates, the psychological cost. Navy psychiatrist evaluation May 1945. Gunnery Sergeant Holloway demonstrates exceptional combat performance with severe psychological burden.

Reports intrusive thoughts related to seeing every kill through eight power magnification. Distinguishes between killing and witnessing killing. States the magnification makes each death personal and memorable. Can recall specific details of all 87 confirmed kills. Face recognition. Circumstances impact observation.

Patient demonstrates classic symptoms of what we term moral injury, not fear-based trauma, guilt-based, not from doing wrong, but from doing necessary things that feel wrong. Patients exact words. The scope shows their faces eight times magnification every night. I know the trajectory was correct. I saved American lives.

But knowing you did the right thing doesn’t make you forget seeing men die because you pulled a trigger. Recommendation. Immediate rotation stateside. Honorable discharge with full benefits. This marine has given enough. Colonel Hirami Yahara survives the war. Captured, interrogated, eventually released. In his postwar writings, he analyzes the American sniper superiority.

We lost Okinawa for many reasons, but American sniper operations represented a fundamental shift in warfare that Japanese doctrine never anticipated. American snipers eliminated over 60% of company grade officers by campaign midpoint. Our experienced leaders were systematically removed. Replacements had no time to learn before they too were killed.

But the greater impact was psychological. Officers could not observe without exposing themselves, could not coordinate without risk. The Americans possessed optical superiority that made our defensive positions transparent while theirs remained opaque. This was not courage versus cowardice. This was physics. They could see 800 m clearly. We could see 300.

No amount of Bushidto spirit overcomes that technological gap. In one documented case, an American sniper deliberately waited 47 minutes for a clear shot to avoid Okinawan civilian casualties. The precision of their optics allowed discrimination between combatants and civilians at ranges where we could barely identify human figures.

This capability saved an estimated 30,000 Okinawan civilians. American snipers could target military personnel without area bombardment. We lost because we were fighting a war of the previous century while America fought the war of this one. 1987 declassified documents. Military historians discover classified Marine Corps intelligence reports.

Pacific theater operational summaries buried in national archives for 42 years. Scout sniper reconnaissance contributions. Guadal Canal. Sniper observations identified 73% of Japanese artillery positions prior to assault. Enabled precision counterbatter fire. Estimated casualties prevented 400 to 600.

Terawa sniper teams provided detailed mapping of defensive positions 3 days before invasion. Adjusted landing plans accordingly. Casualty reduction estimated 15 to 20%. Saipan continuous sniper observation tracked Japanese troop movements, supply routes, command post relocations. Intelligence reports credited with unprecedented situational awareness at battalion level.

Pelu sniper teams identified concealed tunnel entrances, ventilation shafts, communication trenches, mapped 89% of defensive network before assault commenced. Okinawa sniper discrimination between military and civilian positions enabled surgical strikes. Estimated 30,000 Okinawan civilian lives preserved through precision targeting versus area bombardment. Giant Sergeant Emmett L.

Holloway. Individual reconnaissance contributions. 147 intelligence reports filed 1942 to 1945. Detailed Japanese position mapping across five major campaigns. Observed and reported. troop movements, supply routes, defensive preparations, leadership changes, morale indicators, intelligence value assessment significantly exceeded direct combat effectiveness.

One analyst’s note from 1946, Holloway’s 87 kills received commendations, his 147 intelligence reports shaped operational planning across five campaigns. We counted the bodies. We should have counted the battles won because he saw what others couldn’t and reported it. Estimated American lives saved by intelligence Holloway provided.

2,000 to 3,000 casualties prevented through informed operational planning. The real story was never the killing. It was the seeing. Not seeing men die. Seeing everything else. troop concentrations, supply patterns, defensive weaknesses, command structure changes, and reporting it. Eight power magnification wasn’t just for targeting.

It was for reconnaissance. Holloway spent more hours observing than shooting, documented enemy activity, filed reports, provided intelligence that shaped battalion and regimental operations. But nobody counted observations. They counted kills. 87 became his legacy. 147 should have been. Amarillo, Texas, June 1946. EMTT Holay comes home. 24 years old.

Navy cross in a box he’ll never open. 87 confirmed kills in a notebook he’ll never share. His father meets him at the train station, sees his son, sees how much weight he lost, sees the tremor in his hands, sees something broken in his eyes that wasn’t broken when he left. Welcome home, son.

They drive to the ranch in silence. That night at dinner, Emmett’s mother asks careful questions. Where was he stationed? What did he do? Scout sniper mama. Long range shooting like the competitions, the thousandy matches. similar. He doesn’t elaborate. She doesn’t push. The years pass. Emmett takes a job at Pantex plant, tool and die maker. Precision manufacturing.

Uses the same spatial calculation skills that made him deadly, now making peaceful products. 1947. He meets Sarah Mitchell at a church social his mother organizes. Sarah teaches third grade. 22 years old. Kind eyes, patient smile. She notices him immediately. Not because he’s handsome, though he is in that lean West Texas way, but because he’s the only man in the room not talking about the war.

Everyone else telling stories, comparing units, reliving glory. EMTT sits quiet in the corner, drinking coffee, looking at nothing. She approaches. You weren’t in Europe. Pacific Marines. Yes, ma’am. Do you want to talk about it? He looks at her. Really looks. First time he’s made eye contact with anyone since coming home. No, ma’am.

I want to forget I ever saw it. Most women would walk away. Too damaged, too complicated. Sarah sits down. Then let’s talk about something else. They marry 6 months later. She never asks about the war. He never tells until 1952. 1952. Sarah finds the notebook. She’s looking for tax documents in his workshop. Locked drawer. Key in his desk.

Opens it. Black notebook. Worn leather cover. Opens it. Kill number one. Guaddle canal. Lieutenant Ishida. Range 850 yd. Wind 7 mph left to right. Temperature 86° F. Target Japanese officer coordinating platoon. Result: immediate incapacitation. Her hands shake as she reads. Kill number 24. Terawa, Admiral Shibasaki. Range 1,320 yd across water.

Wind 8 mph variable. Temperature gradient 84° F to 92° F. Corololis effect accounted. Target: Japanese naval commander. Result: immediate incapacitation. Command structure collapsed. Estimated 500 plus American lives saved. Kill number 80. Pelu. Target. Age approximately 18. Range 780 yards. Collateral casualty.

Center mass hit. Death not immediate. Suffered approximately 90 seconds. This one I’ll remember differently than the others. Kill number 87. Okinawa. Range 940 yd. Japanese artillery spotter. waited 47 minutes for clear shot to avoid civilian casualties. Target eliminated. Two Marines KIA during weight. Four Okinawan civilians survived.

Did I calculate correctly? 87 entries. 87 men her husband killed. She sits down, processes. The quiet man who makes breakfast for their daughters, who helps with homework, who never raises his voice, who sometimes stares at nothing, killed 87 men. She finds him in the garage. EMTT. He turns, sees the notebook in her hands.

His face goes pale. Sarah, I 87. He can’t speak. She walks to him, doesn’t recoil, doesn’t retreat. Are you okay? The question breaks something in him. Distance collapses through the lens. Eight power magnification every night. I know the trajectory was correct. I saved American lives. The numbers don’t lie. But knowing doesn’t make forgetting possible.

Forget what? Seeing men die because I calculated where to aim. Seeing their faces magnified eight times. Seeing the impact, the fall, every detail. Sarah holds him. Not judgment, not fear, just presence. You came home, she says quietly. You did what you had to do and you came home. That’s what matters. But they both know it’s not that simple because the notebook has 87 names.

And he remembers every face. And coming home doesn’t mean leaving the war behind. It just means carrying it in different places. Do you ever think about them? She asks. Every day. Every single day. What do you think about? Whether they had families, children, wives who waited for letters that never came, mothers who buried sons without knowing how they died, whether any of them saw me before I pulled the trigger, whether they knew.

Sarah doesn’t have answers. Nobody does. She never mentions the notebook again. But she understands now why sometimes he stares at nothing. He’s not seeing nothing. He’s seeing everything too clearly. Magnified eight times forever. 1979 declassification. The Army releases scout sniper operational records 34 years after the war ended.

Amarillo newspaper runs the story. Local hero 87 confirmed kills. Navy cross recipient. Longest confirmed kill, 1,320 yards. Reporters contact EMTT, now 57 years old, still working, still living quietly. He agrees to one interview. One. The reporter is young, enthusiastic, asks about the biggest shot, the most dangerous mission, the closest call. EMTT answers factually.

Terawa, 1320 yards, killed a Japanese admiral, probably saved 500 Marines. The reporter writes it up. Heroic story. American sniper defeats Japanese through superior skill and courage. EMTT reads the article, sets it down. It’s accurate factually, but it misses the point entirely.

The point isn’t the kills, isn’t the range, isn’t the skill. The point is what it costs to see men die magnified eight times and carry those images for 34 years. But you can’t explain that to someone who wasn’t there. So, he doesn’t try. 1995 museum donation. Emmett is 73 years old, retired. Sarah passed two years ago, daughters grown, grandchildren asking questions about Grandpa’s war.

He decides it’s time. Donates his M1903A1 with the original Unertle scope to the National Museum of the Marine Corps. The rifle that killed 87 men at ranges the enemy thought were safe. The scope that showed 87 faces in perfect clarity. They mounted in a display case. Glass temperature controlled preserved.

The placard reads M1903A1. Rifle with unertal 8 time scope used by JI Sergeant Emmett L. Holloway USMC87. Confirmed kills Pacific Theater 1942 to 1945. Engagement range 650 to 1,100 yards. This weapon system represented 40 years of American civilian marksmanship tradition adapted for war. Japanese forces possessed no equivalent technology or institutional knowledge base.

The 8 power magnification provided not only targeting capability but reconnaissance superiority that shaped operational planning and enabled discrimination between combatants and civilians at extreme range. Ji Sergeant Holay filed 147 intelligence reports during his service. Estimated 30,000 Okinawan civilians survived due to precision targeting this system enabled.

EMTT reads the placard at the dedication ceremony. Everything factually correct. Finally, someone counted the observations, not just the kills. 147 reports. Pierce was right. Count what you saw that saved others. 2001 final interview. EMTT is 79 years old, frail, hands shake constantly now, vision degraded, but mind still sharp.

A military historian contacts him, writing a book about Pacific War sniping. Once the real story, not the heroic narrative, the truth. EMTT agrees. They sit in his living room in Amarillo. Tape recorder running. The historian asks, “What was it like being one of the best snipers in the Pacific?” EMTT is quiet for a long moment.

I wasn’t the best sniper. I had the best optics. The Unertle 8 power scope was developed by civilian competition shooters. Decades of perfecting long range precision, not for war, for sport. Japanese military never knew American civilians shot thousand yards for fun. Their intelligence completely missed it. No civilian gun culture means no context for what we were doing.

When I killed 87 men at ranges they thought impossible. I wasn’t superhuman. I was using equipment developed over 40 years by sportsmen. But here’s what the history books don’t tell you. Better equipment means you see more. Eight power magnification shows faces, shows fear, shows the moment of impact, shows death in perfect clarity.

I won because I could see better. But seeing better means remembering clearer. I also filed 147 intelligence reports, observed enemy positions, tracked movements, mapped defenses. That information shaped operations, saved thousands of lives. But nobody counted that until 1987 when they declassified the reports. They counted 87 kills.

Should have counted 147 observations. Master Gunnery Sergeant Pierce told me before he left, “Don’t just count the kills. Count what you saw that saved others.” Took me 40 years to understand what he meant. The seeing was always more important than the shooting. Is that victory? Maybe. Is that a burden? Absolutely.

The thousand-y stare isn’t from seeing nothing. It’s from seeing too much, too clearly, too far away. People thank me for my service. I appreciate that. I did my duty. I protected Marines. I helped win the war. But at night, when I close my eyes, I don’t see victory. I see 87 men magnified eight times. see them clearly like they’re right in front of me like it happened yesterday instead of 60 years ago.

And I see all the things I observed. Enemy positions that got hit with artillery because I reported them. Supply routes that got interdicted. Defensive weaknesses that got exploited. That intelligence saved more lives than the killing. But the faces are what stay with me. Perfect vision, perfect memory, perfect clarity.

I can’t unsee what I saw. Nobody can. EMTT Lancaster Holloway dies February 14th, 2003. Age 81, Amarillo, Texas. Marine Honor Guard, 21. Gun salute, flag folded and presented to his daughters. The eulogy mentions his service, his Navy cross, his postwar life, devoted father, skilled craftsman, quiet patriot. 87 kills are never mentioned. at his request.

He wanted to be remembered as a father, not a killer. His notebook, 87 entries, 87 faces, is donated to the museum with instructions, arrant words. They counted 87 kills. Should have counted 147 intelligence reports. The seeing was always more important than the shooting. The M1903A1 Springfield with unertime scope remains in the museum today.

Perfect preservation. Climate controlled, protected. The rifle that changed Pacific War sniping. The scope that gave America technological superiority. Japan could never match. the equipment that killed 87 men and saved thousands of Americans and Okinawans through precision targeting and reconnaissance. Visitors see the rifle, see the scope, read about the 1320 yard shot that killed an admiral.

They see the technology, the achievement, the victory. Some read deeper, learn about the 147 intelligence reports, the reconnaissance value, the lives saved through observation. But they don’t see the cost because the cost isn’t visible in glass cases. The cost is carried in memory, in nightmares, in the thousand yard stare of men who saw too much through scopes that showed everything.

EMTT Holloway saw 87 men die at distances they thought were safe, saw them magnified eight times, perfect clarity, perfect detail, and observed enemy positions for 3 years. filed 147 reports, shaped battles, saved thousands. That’s the complete story. Not just the kills, the seeing, the intelligence, the reconnaissance, and the weight of remembering what you cannot forget.

The thousandy stare, not from distance, from seeing everything too clearly forever.