December 16th, 1944. Our den forest, Belgium. The snow is falling hard. The sky is a dull iron gray and visibility is nearly zero. Through the static mist, German artillery thunders relentlessly. A barrage pounding American lines with terrifying precision. Men crouch in their foxholes, frozen, deafened, waiting.

Then faintly the Americans answer back. But this time, something is different. Shells burst above the treetops and not on impact, but in midair, raining deadly fragments on advancing German troops. Entire squads vanish in seconds. German soldiers look upward, confused. The shells are exploding at the perfect height, as if the air itself had turned against them.

No one on the ground knows it yet. But this isn’t luck. It’s a weapon so secret most of the men firing it don’t even know how it works. A weapon that doesn’t wait for contact. A weapon that senses its target. A tiny radio brain sealed inside a steel shell. The most advanced technology the world had ever hidden in plain sight.

This is the story of the radar proximity fuse. The invisible invention that changed the very nature of war. In the early years of World War II, one of the allies greatest weaknesses wasn’t courage or numbers. It was accuracy. Anti-aircraft gunners from the beaches of Britain to the decks of Pacific destroyers were fighting a losing battle against speed, altitude, and chaos. Picture it.

1940, the Blitz. German bombers scream through the night sky over London, their engines echoing through the clouds. Below, anti-aircraft crews crank their guns skyward, calculating range and lead angles by hand. Every shell they fire must explode near the target, but only if they can guess the right time. Each round is fitted with a mechanical time fuse, a tiny clockwork mechanism set to detonate after a specific number of seconds.

If the timing is wrong by even half a second, the shell either bursts harmlessly in empty air or detonates too late behind the fastmoving aircraft. The result, for every hundred shells fired, only one might explode close enough to cause real damage. By 1941, the situation had grown desperate. The US Navy, watching the rise of Japan’s aerial power in the Pacific, knew that even the mightiest battleship was vulnerable from above.

A well-amed dive bomber could end a vessel worth millions, while anti-aircraft fire often wasted thousands of rounds to score a single hit. Scientists and military engineers understood the problem perfectly. You could aim faster. You could build bigger guns, but you couldn’t outg guess gravity or time.

The true challenge wasn’t firepower. It was proximity. What if instead of exploding after a set time, a shell could sense when it was close enough to its target? That idea had existed since World War I, but back then it was little more than science fiction. No one had the technology to build a thinking fuse small and strong enough to survive the crushing force of a gun’s launch.

A shell leaves a 5-in naval gun at over 2,500 ft per second, generating more than 20,000 gs of acceleration. Any sensitive electronic device would be shattered to dust the moment the trigger was pulled. So by 1941, the world’s greatest minds in America and Britain alike were searching for a miracle that didn’t seem possible. And in a quiet lab in Maryland, that miracle was about to be born.

It began quietly in 1940, long before Pearl Harbor. Britain was fighting for survival, bombed nightly by the Luftvafa. America was still neutral, but watching closely. The Royal Navy’s ammunition expenditure against German aircraft had reached staggering levels, and the success rate was abysmal. The British needed a breakthrough, something that could multiply their defenses overnight.

So they reached across the Atlantic. In September 1940, a secret delegation known as the Tizzarded Mission arrived in Washington. DC inside their briefcases was the heart of British wartime science. Radar, jet engine plans, and a mysterious concept for a proximity fuse that could detonate itself when near an aircraft. The Americans listened.

Then they promised something the British couldn’t match at that time. industrial power on an unlimited scale. The project was immediately classified top secret. It would be handled by a newly formed division under the US Office of Scientific Research and Development led by physicist Dr. Merl Tuve of John’s Hopkins University.

They called the unit simply Applied Physics Laboratory APL. And their mission was impossibly bold to create a tiny electronic brain that could survive the most violent forces on Earth. Tuveet and his team knew what they needed, a fuse that could sense a nearby aircraft using radio waves, similar to how radar detects objects.

The idea was revolutionary. Each shell would carry a miniature radio transmitter. As it flew, the transmitter would bounce signals off anything nearby. If the returning signal grew stronger, meaning a target was close, the fuse would automatically detonate. In theory, the concept was simple. In practice, it bordered on madness.

The technology of the early 1940s was bulky, fragile, and power- hungry. Radios were made with vacuum tubes, not transistors. Delicate glass cylinders that shattered easily. To fit that inside a spinning, exploding shell seemed absurd. But Tuve refused to quit. He recruited some of the finest engineers and physicists in America. Men and women from RCA, Bell Labs, and the National Bureau of Standards.

Their laboratory buzzed day and night with soldering irons, oscilloscopes, and calculations scribbled in chalk. Each failure was violent. Prototype fuses exploded too early, too late, or not at all. But with every test came progress. By mid 1941, the breakthrough arrived. A small, rugged miniature vacuum tube only a few centimeters long that could endure the shock of being fired.

It had been designed by RCA engineers and refined by Tuve’s team until it was nearly indestructible. To power it, they built a tiny battery that activated only after the shell was fired using centrifugal force to mix chemicals inside and start the current. Now the fuse could live, think, and react all within milliseconds.

By late 1942, tests were showing staggering results. Anti-aircraft shells equipped with the new VTfuse, short for variable time, were detonating within lethal range of target drones. Hits that once required hundreds of rounds now took only a handful. President Franklin D.

Roosevelt personally classified the project’s results as higher than top secret. The proximity fuse was to be guarded with the same secrecy as the atomic bomb. No shell with the new fuse could be fired over land where it might fall into enemy hands. Only naval units were allowed to use it, and even they had to destroy every dud or misfire before the enemy could recover one.

It was in every sense a hidden miracle, a weapon that could think, react, and kill more efficiently than any human calculation. And soon it would face its first true test, not in theory, but in battle. When the proximity fuse entered combat, it didn’t just destroy targets. It changed how wars were fought. To understand why, we have to look at it from several angles.

The human, the tactical, the technological, and the psychological. Before the proximity fuse, anti-aircraft gunners lived on guesswork. They fired blind into the sky, predicting where an aircraft might be by the time their shell arrived. Even the best crews only scored one hit in thousands of rounds. The frustration was palpable, especially when kamicazis or dive bombers streak straight toward their ships.

Then came the new fuse. Suddenly, the men on deck noticed something strange. Their shells were bursting closer. The sky lit up around enemy planes, shredding wings and engines mid dive. Targets that once slipped through curtains of flack now exploded in bright mid-air flashes. A sailor aboard the USS Helena later recalled, “Before we’d fire until our barrels melted and prey with the new fuses, the sky itself seemed to fight back.

The psychological change was enormous. For the first time, gunners felt the odds tilt in their favor. They weren’t guessing anymore. They were hunting. And that confidence would soon prove decisive in the Pacific.” By 1943, the US Navy had armed its 5-in shells with proximity fuses. The timing couldn’t have been better. Japan’s air attacks were growing more desperate, and Allied fleets were pushing closer to enemy shores.

The first combat use came in the Solomon Islands campaign in January 1943. Off Guadal Canal, Japanese bombers roared in low over the sea, aiming for the cruiser USS Helena. Gunners loaded shells marked only with small VT initials. Few even knew what those letters meant. The results were devastating. As the shells burst near the attackers, several Japanese planes disintegrated before reaching bomb release range.

Others turned away, crippled and smoking. The ships below were untouched. Admiral William Hollyy sent a oneline message to Washington. This new fuse is worth its weight in gold. The proximity fuse had drawn its first blood, and the Navy would never fight the same way again. What made the VT fuse extraordinary wasn’t just that it worked, it was how it worked.

Each shell contained five precision components that had to survive forces up to 20,000 ages, the same as slamming into a concrete wall at supersonic speed. Inside that steel casing sat a fragile brain, a miniature transmitter, receiver, amplifier, and power source. All tuned to detect echoes from nearby targets. The instant those returning waves intensified, the circuit completed. The detonator fired.

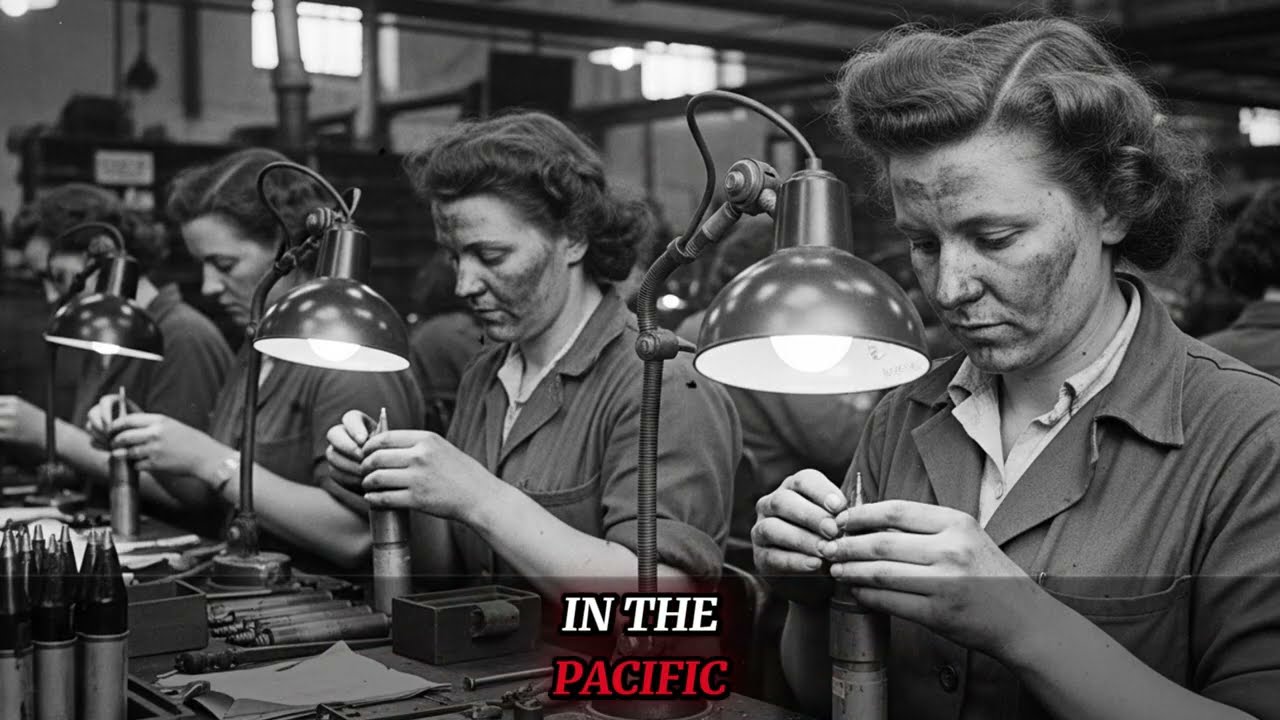

The explosion occurred at exactly the right distance for maximum damage. Every fuse was assembled by hand, often by women working in ultra seccure facilities across the US RCA. Eastman, Kodak, and General Electric all played parts, building over 22 million fuses during the war. It was the perfect fusion of science and industry.

The invisible edge that turned technology into survival. And yet, this success came with danger. If even one fuse fell into enemy hands, the secret could unravel everything. So, when the army demanded to use them on land, especially in Europe, the War Department hesitated. The fuse’s true test on land would have to wait for the moment America needed it most.

Imagine a single fleet action where the sky itself becomes a weapon. Not because you have more guns, but because each shell now knows when to die. The proximity fuse turned quantity into quality. Where fleets once poured lead into clouds of tracer and smoke. They now achieved lethal density with far fewer rounds. That mattered in two crucial ways.

First, logistics. firing less to get more men. Ships spent less time reloading and more time maneuvering. Ammunition stock stretched farther out into the Pacific. Convoys survived longer. Supply lines held in a war defined by distance that mattered as much as any battle plan. Second, tactical doctrine shifted.

Commanders adapted quickly. Destroyer captains who had once masked flack in defensive rings discovered they could place batteries in overlapping arcs and trust the fuses to detonate at optimal kill ranges. Escort formations evolved. Kamicazi tactics lost the stealth they’d once relied on. Naval air defense became anticipatory instead of reactive.

The effect ashore was no less dramatic. In Europe, artillery shells armed with VT fuses detonated above ground, sending lethal fragments down over advancing formations. Concentrated barges could now neutralize an attack in mid-motion for commanders on both sides. The calculus changed. Defensive positions became exponentially deadlier.

Offensives required rethinking. This was not incremental. It was exponential. A single battalion’s effectiveness multiplied simply by changing when the shells exploded. Strategically, the fuse shortened timelines. It made holding ground cheaper in blood and time. It made assaults costlier. It rewrote margins commanders had relied on for months.

And all this happened before the enemy truly understood what hit them. From the German high command to Imperial staff rooms in Tokyo, the proximity fuse generated bafflement. Reports began trickling in. Pilots who had executed low-level approaches without loss now found the sky erupting around them. Tankers whose choreographed columns had once rolled unmolested now watch shells explode above the road, shredding the leading elements and blinding the drivers.

Axis analysts looked for patterns. They studied fragments recovered from battlefields. They interrogated prisoners. They improvised countermeasures. The Germans launched experiments in radio direction finding. Convinced the Allies had placed remote detonation mechanisms on ships or rooftops.

They tested insulating coatings, attempted electronic jamming, and developed dummy targets, searching for a trigger. The Japanese were equally mystified at first. Their kamicazi pilots trained to strike holes and hang on until impact, found some aircraft vaporized before contact. Some commanders concluded incorrectly that Allied Flack had somehow shifted to a new predictive algorithm.

They adapted by changing altitudes, approaches, timings. Adaptation helped, but only by degrees. Crucially, the axis could not duplicate the fuse. It was not merely a question of manufacturing capability. It was a question of secrecy. Raw materials and industrial process. The tiny vacuum tubes, the specialty batteries, the hermetically sealed assemblies.

These were not trivial to copy, especially under the bombs and blockades the Axis faced. Thus, the enemy’s responses were slow and inefficient. They chased ghosts while the allies refined a weapon that was already changing the battlefield. Deploying the proximity fuse required more than engineering. It required leadership willing to accept two unpalatable risks.

The chance of friendly loss due to dud fuses and the political risk that the secret might leak. The war and navy departments heatedly debated over land use. If a shell with a VT fuse landed intact on friendly soil, the enemy could recover it, analyze it, and potentially neutralize the advantage. So, initial policy forbade using VT overland.

Naval battles at sea became the proving grounds. That policy forced tactical creativity. Navy leaders kept the fuses aboard ships, but under strict accounting. Every dud recovered had to be destroyed under guard. Reports were sanitized. Crews were told a cover story. Sailors fired with a weapon many didn’t fully understand.

Their commanders had to put trust in laboratory claims, in test fires, and in the intuition of physicists whose language, microscond timing, and echo thresholds sounded abstract to deck sergeants. What commanders gained in secrecy they risked in vulnerability. The decision to later allow careful use over select land battles after confidence in safety protocols grew reflected a new kind of wartime leadership, one that married scientific evidence with battlefield necessity.

Leaders who embraced the fuse early reaped disproportionate gains. Those who hesitated watched opportunities pass. A weapon that maximizes lethality while minimizing waste raises an uncomfortable question. Does increased efficiency make killing any easier? Some scientists involved in the VT project later reflected on this.

Their answers were not uniform. Many believed the fuse saved lives. Allied sailors and soldiers who would have otherwise died under indiscriminate bombardment. By producing more predictable, effective air and ground defenses, fewer attackers penetrated defenses, and fewer defensive crews endured prolonged exposure. Yet others felt unease.

They had built a device that rendered human proximity irrelevant. The fuse detonated not because a human judged the precise moment, but because a circuit said so. That mechanization of death carried philosophical weight. Military ethicists later debated whether the technology crossed a line. The consensus among wartime policymakers leaned pragmatic.

If a technology saves your side more lives than it costs the enemy, it is a contribution to victory. The calculus was cold but decisive. In postwar reflections, some engineers framed their work as grimly humanitarian, reducing protracted engagements, shortening conflicts, saving the lives of rounded up sailors on a ship’s deck.

Surgeons who treated fewer burn victims and pilots who flew fewer desperate fuel starved sorties sometimes agreed. Still, the moral debate continued. The proximity fuse had changed not only how wars were fought, but how people thought about the agency of killing in modern combat. Finally, consider legacy. The proximity fuse was not an isolated invention. It became a seed.

The science behind VT, miniaturized electronics, ruggedization techniques, timed activation, and remote sensing fed postwar developments. Guided munitions, missile proximity sensors, and modern fusing logic trace technical ancestry to those wartime labs. The tiny vacuum tubes gave way to transistors. The fuse’s brain grew smarter, smaller, embedded.

Yet the original fuse remained uniquely powerful because it married small-cale electronics to mass-produced ordinance at a scale both industrial and tactical. That convergence, science, manufacturing, and operational doctrine is the real story. The proximity fuses success showed that a technological secret could become a strategic lever if it was mass-produced, tightly controlled, and ruthlessly applied.

And that in the end is why the fuse mattered beyond the flash and the shrapnel. It taught civilization how to turn a laboratory advantage into a battlefield difference. The battlefield would soon test those lessons. The Fuse’s most dramatic proving moments lay ahead. Moments that would determine fleets, ground offensives, and perhaps the tempo of the war itself.

It was the coldest winter Europe had seen in half a century. The Arden Forest lay under a heavy white silence until without warning the quiet broke. On December 16th, 1944, at precisely 5:30 a.m., over 1,600 German artillery guns roared to life. Flames tore across the forest floor. And within minutes, the American front, stretched thin and unprepared, was engulfed in chaos.

Hitler’s operation Vamrine, better known as the Battle of the Bulge, had begun. For the next few days, the Vermach surged forward under blinding snow and fog. Allied aircraft were grounded, infantry regiments fell back, communications collapsed, and entire roads vanished under retreating convoys. But in one sector near the town of Bastonia, the German offensive would face something entirely new.

American artillery men had been issued experimental fuses labeled only as VT. They didn’t know what the initials meant. They were simply told they explode near the target, not on it. By December 23rd, the skies cleared just enough for the first tests in combat. At 1100 hours, the 406th Field Artillery Group received fire missions against advancing German infantry columns near Marvy.

The Americans aimed high, letting their shells arc into the sky, set with the mysterious VT fuses. Seconds later, something remarkable happened. Instead of burying themselves in snow or mud, the shells burst midair. Precise lethal clouds of fragmentation raining down across the open field. The German infantry, accustomed to diving for cover at the sound of incoming fire, were caught in the open.

Every man who looked up saw the snow itself exploding. A single salvo from three American batteries halted an entire battalion in its tracks. Survivors later described it as the sky disintegrating. Before that day, artillery was a guessing game. You adjusted fire by sound, by spotting, by the slow arithmetic of range tables and reports.

You hoped your shells landed close enough, but now the fuse did the math. Each shell, armed with a tiny radio brain, sensed the approach to the ground or an object beneath it. It detonated at exactly the height that guaranteed maximum spread. No human adjustment, no delays, just instant optimization. In the dense forests and narrow valleys of the Arden, this meant one thing.

German attacks lost momentum. Every assault that tried to mass under cover of trees was shredded from above. The fuse effectively nullified the advantage of terrain, the very advantage on which the German offensive depended by December 25th. As the 101st Airborne fought for survival in Bastonia, American artillery blanketed the surrounding ridges with VT fuses.

The explosions hung in the air like burning chandeliers. Commanders radioed back in disbelief. It’s working better than anyone dared hope. While snow fell over Europe, half a world away, the Pacific was on fire. In early 1945, the US Navy was locked in desperate battles off Luzon and Okinawa, facing the most dangerous weapon Japan had left, the kamicazi.

Conventional anti-aircraft fire was often feudal. Pilots flew too fast, too low, and too erratically for impact fuses to respond in time. Ships might fire hundreds of shells and hit nothing. Then came the proximity fuse. At first, only a few ships carried them. The Navy tested them cautiously, guarding the technology as if it were nuclear.

But once the results came in, hesitation disappeared. A kamicazi dive typically lasted 15 seconds. With VT shells, those 15 seconds became eternity. Destroyers and carriers formed tight overlapping kill zones. As suicide planes broke cloud cover, they entered a storm of air bursts, shells exploding around them, ripping wings and control surfaces apart before the aircraft could descend.

Radar tracking would call range and bearing, guns would elevate, and the fuses would do the rest. The USS Missouri, USS Enterprise, and dozens of other warships credited VT ammunition with saving their crews during Okinawa. For every kamicazi that made it through, 10 disintegrated midair. In one engagement on April 11th, 1945, the battleship USS Missouri recorded four confirmed kills within 90 seconds.

All without a single impact hit. The air itself had turned lethal. The Allies guarded the VT fuse more tightly than almost any other wartime secret, including early radar and codereing systems. Even during the Arden’s campaign, strict orders prohibited its use where dud shells might be recovered. Commanders risked court marshall if they ignored the directive.

But by the end of December 1944, the situation was too dire. The German advance was still threatening to cut Allied lines. General George S. Patton, driving his third army north toward Bastonia, made the call, “Use everything you’ve got.” And with that order, the VTfuse saw its first large-scale use over land. The effect was immediate.

German units reported catastrophic casualties from invisible air bursts. Soldiers refused to advance. Some divisions halted attacks entirely, convinced that the Americans had invented an air minefield. The tide of the Arden began to turn. What radar had done for detection, the proximity fuse now did for destruction, but the true scope of its impact, and the full scale of what it achieved was about to be revealed.

January 1945. The turning of the tide by the first days of January 1945. The German offensive that had begun with such fury was crumbling. The once bold thrust through the Ardennis had slowed to a crawl, then to silence. A silence punctuated only by the concussive rhythm of Allied artillery. Those guns from Bastonia to St.

Vith were now using proximity fuses as standard issue. Each shell burst with mathematical perfection. at treetop height over roads behind ridgeel lines. Columns that once relied on darkness or forest canopy for protection found no refuge captured German officers would later report that their men were psychologically broken by the invisible precision of American fire.

They described the same scene over and over, a sudden storm of detonations erupting in midair, slicing through ranks before anyone could drop flat. One veteran of the 26th Volk Grenadier Division said it was like the sky itself had decided to shoot us. This wasn’t simply a battlefield improvement. It was a transformation of doctrine.

For the first time, artillery was not just suppressive. It was predictive. Each explosion anticipated movement rather than reacting to it. By January 15th, German generals had begun ordering withdrawals, not just from lack of supplies, but because their formations could no longer move in daylight without devastating losses.

The VT Fuse had effectively stolen mobility from the Vermacht. And when mobility dies in war, momentum follows. At the same time, 8,000 mi away, the Pacific theater was entering its bloodiest phase. The Philippines campaign was grinding forward. Japanese forces pushed back to the islands of Luzon and Muro, fought with fanatical desperation.

The Imperial Japanese Navy had been all but destroyed. Its pilots, young, barely trained, and indoctrinated to die, were now its most dangerous weapon. From the decks of American carriers, gunners watched the horizon through smoke and salt spray. They knew what was coming. Waves of aircraft flying straight into their ships.

Before the proximity fuse, those final seconds were chaos. Tracers ripping the air, shells detonating too early or too late. But now, for the first time, the gunners had help from physics itself. Every round they fired created an invisible sphere of death, a radius of perfect timing. A kamicazi diving from 2,000 ft had only one chance to live if the fuse somehow didn’t see it. Most never made it that far.

Reports from Navy action logs read like science fiction. At Okinawa, destroyers operating picket duty, the most dangerous position in the fleet, were now able to defend themselves with unheard of efficiency. The USS Hugh W. Hadley, during one desperate day of attacks, claimed 23 kills in 80 minutes, with proximity fused ammunition accounting for the majority.

The sky above the ship resembled a storm of suspended lightning. bright white flashes perfectly spaced cutting through waves of aircraft. A single shell might not hit a plane directly. It didn’t need to. All it needed was proximity. And proximity, it turned out, was everything. For the first time in modern naval history, defensive fire became predictable.

Commanders could calculate kill zones, timing, and even survival odds based on data, not hope. The VTfuse had transformed every anti-aircraft gun into a sensor-based weapon. Decades before computers or guided missiles would appear. Even as the technology saved fleets and divisions, the Allied High Command guarded it with fanatical caution.

The British code named it variable time or VT, a vague label designed to conceal its nature. Its existence was compartmentalized to a handful of trusted commands. Captured munitions were to be destroyed instantly. If a dud shell landed unexloded, retrieval teams risk their lives to recover it. The fear was simple, that the axis might reverse engineer the device and turn the tide once again. The fear was justified.

Unknown to the Allies, German scientists had already been experimenting with their own radio fuses, but their designs were fragile, their materials inferior, and their research hopelessly delayed by Allied bombing. By the time the Americans were firing VT rounds in the Arden, the Germans were still struggling to make a prototype survive the launch shock.

That gap in capability, a few months of progress, was enough to ensure the war’s direction would never reverse again. In the months that followed, as Allied air superiority became total, one phrase began to circulate in secret briefings. The proximity fuse in our greatest secret since the atomic bomb. Admiral Lewis Strauss of the US Navy called it the most significant new development in ammunition since gunpowder.

Others simply referred to it as the fuse that won the Yika war. It wasn’t an exaggeration, neutralizing the kamicazi threat and breaking the last German offensive. The proximity fuse had done something that no single weapon before it had achieved. It had changed the rules of engagement for both land and sea.

When the atomic bomb finally fell on Hiroshima, most of the world saw it as the dawn of a new age. But the truth is that the scientific revolution that made it possible had already begun quietly, invisibly inside the nose of a 5-in shell. Because before the atom split the sky, the fuse had already made the sky lethal. The snow of the Arden still clung to every branch, every frozen footprint.

Yet the front lines had shifted irrevocably. What had begun as a bold German offensive was now a smoldering, disorganized retreat. American artillery units armed with proximityfused shells had reshaped the battlefield. Commanders who had once worried about supply lines now celebrated their firepower as decisive. The 101st Airborne Division surrounded in Baston noted in their afteraction reports, “The air bursts from enemy shells were unlike anything seen before.

They shredded cover and disoriented the enemy without warning. Morale among our troops remained high as the destructive force worked in our favor. Across multiple sectors, similar reports appeared. Infantry units had been forced to hold positions they would have abandoned simply because the enemy could no longer advance without catastrophic losses.

The proximity fuse effectively neutralized the advancing mechanized columns of the Vermacht. Tanks that had once been the spearhead of Blitzkrieg were slowed, forced to remain undercover, or in some cases destroyed before reaching the line. German soldiers, illprepared for the invisible threat raining down from above, reported psychological effects as severe as the physical, officers recorded entire platoon refusing to move during daylight.

Some wrote of men trembling at the sound of incoming shells, unsure if the next explosion would be fatal. Half a world away in the Pacific. The story was equally transformative. During the Battle of Okinawa, the Proximity Fuse turned anti-aircraft fire from a reactive gamble into a predictive shield. Ships previously vulnerable to suicide attacks were now defended by near infallible mid-air detonations.

From the decks of the USS Tennessee to the USS Missouri, the logs described waves of kamicazi aircraft destroyed before they could reach the fleet. Officers noted that every missed aircraft was a statistical anomaly. The fuse allowed gunners to focus not on individual planes, but on defensive patterns, overlapping kill zones, synchronized salvos, and preemptive barges that reduced exposure time and increased survivability.

Admiral Raymond Spruent, reviewing operational reports from the fifth fleet, remarked, “The proximity fuse has fundamentally changed the calculus of anti-aircraft defense. losses are dramatically reduced and the effectiveness of our fleet is now measured not only by offensive action but by survivability under attack.

While exact figures remain contested, historians estimate that proximity fused shells destroyed or neutralized tens of thousands of enemy combatants by the wars end. In Europe, Arden’s campaign, thousands of German infantry casualties, dozens of tanks stalled or destroyed, entire battalions immobilized. In the Pacific, Okinawa and Luzon, hundreds of kamicazi planes destroyed midair.

Dozens of ships spared from direct hits, countless lives saved. Even conservative accounts agree. Without the fuse, Allied casualties would have been significantly higher in both theaters. The Germans, upon capturing evidence of the proximity fuse, were initially baffled. Laboratory analysis revealed the delicate radio mechanisms and miniaturized timing devices inside shells.

Even if reverse engineered, the knowledge came too late to affect the war’s outcome. The fuse had already influenced the decisive moments of the final allied offensives in Europe and the Pacific. The Japanese likewise had no comparable technology. Their massed air assaults faced a defensive advantage that no conventional tactics could overcome.

The success of the VT Fuse did more than alter one battle or campaign. It demonstrated a new principle. Precision combined with automation multiplies human effort exponentially. Artillery and anti-aircraft gunners were no longer constrained by human reflex or visibility alone. The fuse turned ordinance into intelligent munitions, foreshadowing the guided missile and smart weapon revolutions of the postwar era.

Yet the immediate effect was undeniable. It saved lives, broke offensives, and accelerated the end of the war in both Europe and the Pacific. The VT Fuse was small, unassuming, and deadly. A true secret weapon whose impact rivaled even the most famous innovations like radar or codereing. As historians later noted, the war had been won not only by men and machines, but by the invisible hand of timing, physics, and engineering, all encoded in a tiny lethal fuse.

With the war officially over in September 1945, the VTfuse’s legacy began to unfold in both overt and subtle ways. Military analysts poured over action reports from the Arden, the Rine crossings, Okinawa, and Luzon. Every log, every diary entry, every captured German or Japanese report highlighted the Fuses decisive role.

The US Army and Navy began immediately incorporating lessons learned into postwar doctrine. Proximity fuses were not just a battlefield curiosity. They became the blueprint for a new generation of munitions. Guided shells, proximity triggered anti-aircraft missiles and later smart bombs. Even before the Cold War had fully started, scientists and engineers were translating VT principles into early missile guidance systems.

The miniaturization of electronics and the concept of detonation timing based on proximity were now seen as the foundation for a future in which ordinance could act almost autonomously. Beyond technology, the fuse reshaped military thinking about psychological warfare and tactical planning. For the first time, commanders realized that the mere threat of a weapon could immobilize entire formations.

German and Japanese troops had reported hesitation, fear and panic not from superior numbers but from the invisible unpredictable death reigning from above. In training manuals after the war, US artillery instructors emphasized the importance of anticipation over reaction, a principle that originated directly from the VT fuses battlefield use.

The notion of preemptive fire mathematically calibrated became a standard. Secrecy remained a paramount lesson. The fuse’s effectiveness was partly due to its invisibility to the enemy. Only a handful of Allied officers and engineers knew its true function. Postwar studies recommended compartmentalization for all advanced military technology, a lesson applied to nuclear weapons, jet propulsion, and guided missiles.

The VTfuse had shown that technological superiority could be nullified if the enemy was allowed to understand it too soon. In naval history, the VTfuse is credited with transforming anti-aircraft defense. At Okinawa, destroyers and picket ships faced kamicazi waves with near fatal efficiency. The doctrine developed in 1945 informed the US Navy’s cold war air defense systems, including Talos, Tartar, and later standard missile systems.

Ship captains came to rely on predictive fire patterns, overlapping kill zones, and automated detection. All principles tested in wartime. Thanks to the fuse, by the early 1950s, the concept of proximity detonation influenced the development of guided anti-aircraft artillery, early surfaceto-air missile systems, smart munitions with proximity and impact triggers.

Historians now regard the VT Fuse as the first smart weapon in modern warfare, predating electronics guided missiles by nearly a decade. Despite its success, the Fuse’s human impact was sobering. Thousands of enemy soldiers were killed in seconds, but countless lives were spared on the Allied side. Many soldiers who served with VTe equipped artillery described the fuse as both a guardian and a terror.

It allowed them to hold positions that would otherwise have been untenable and inflicted a psychological blow that lasted decades. Medals and commendations were awarded, though few could fully convey the influence of a fuse. Its most significant recognition came not through ceremony but through historical record as an unsung technological hero of World War II.

The VT Fuse had demonstrated a fundamental truth. Small precise technological innovation can alter the fate of armies, fleets, and campaigns. Without it, the Arden’s counteroffensive might have succeeded. Okinawa’s picket line might have bled more heavily, and the Pacific theat’s cost in human life would have been immeasurably higher.

From its inception in secret laboratories to its deadly, unseen orchestration over battlefields worldwide, the proximity fuse had earned its place as a weapon that changed not just battles, but the philosophy of warfare itself. The stage was set for the Cold War, guided munitions, and the modern age of precision artillery, all built on the foundations of this tiny lethal device.

The war had ended, cities lay in ruins, fleets returned to harbors, and the echo of battle faded into memory. Yet the impact of one tiny piece of engineering, the VT proximity fuse, remained palpable. It was small, unassuming, yet transformative. In the hands of Allied artillerymen, it became both shield and sword, reshaping the battlefield before the enemy could even react.

Entire formations were immobilized. Mechanized advances slowed and countless lives, both allied and civilian, were spared. But the Fuse’s legacy extended beyond statistics. It represented a shift in warfare from brute force to intelligent application of technology. It forced commanders to rethink strategy, emphasizing anticipation, precision, and psychological dominance over sheer volume of fire.

The war had proven that the mind of the engineer could be as decisive as the courage of the soldier. Historians today view the VTfuse as the first true smart weapon of modern warfare. A harbinger of guided missiles, precision munitions, and automated defense systems. Its invisible hand reached across continents from the frozen Arden to the tropical shores of Okinawa, turning fear into control, hesitation into opportunity.

Yet the human dimension remained. Gunners reported a strange duality. Awe at the technology, terror at its effects, and respect for the men who wielded it with deadly efficiency. It was a weapon of science, but also of humanity, saving countless lives by making artillery more effective, less indiscriminate.

In the end, the VTfuse reminds us that history is not only shaped by generals and soldiers, but by the small, ingenious inventions that tilt the balance in ways unseen and often unrecognized. A tiny fuse buried inside a shell, became one of the war’s most decisive instruments. It altered the course of battles, the strategies of armies, and the very philosophy of modern warfare.

From Normandy to Okinawa, from Arden forests to Pacific skies, its impact was silent, precise, and absolute, a quiet revolution in the art of destruction. The Atlantic and Pacific theaters were forever changed, not just by men, but by the ingenuity that gave them an edge they could not have imagined a decade before.

And so in every history book, in every military analysis, in every recollection of those final battles, the VT Proximity Fuse stands as a testament to human ingenuity. Small, invisible, and unstoppable.