For 27 Nights Straight, a DOGMAN Visited the Church, What Happened on the 28th Was Unbelievable!

The 28th Night

They told me evil doesn’t knock before entering. They were wrong. For 27 nights, something scratched at our church doors at exactly 3:17 a.m. On the 28th night, we finally opened them.

I’m 71 years old now. I spent 43 years as a pastor in a small rural church in northern Idaho. I’ve counseled the dying, buried children, and sat with families through unimaginable pain. But nothing—absolutely nothing—prepared me for what happened during those 28 nights in the winter of 1997.

This story has never been written down until now.

.

.

.

My name is Thomas Whitmore. In November of 1997, I was 44, serving as pastor of Shepherd’s Grace Community Church in the mountains outside Coeur d’Alene, Idaho. Sixty members on a good Sunday, mostly logging families and ranchers. The church was over a hundred years old, built of local timber and stone, nestled on five acres of forest, twelve miles from the nearest town. I lived in the small rectory attached to the church—alone, since my wife Margaret had passed three years before.

The solitude suited me. My days were predictable: mornings in study and prayer, afternoons visiting congregation members, evenings preparing sermons or reading. The church was traditional—wooden pews, a worn sanctuary, my office, a fellowship hall in the basement, and a bell tower that hadn’t rung in decades.

November in northern Idaho is cold. That year, the first heavy snow fell on November 18th—two feet overnight. I spent the day shoveling paths from rectory to church, church to parking area, parking area to road.

That night, it began.

I went to bed around ten, a light sleeper since Margaret died. At 3:17 a.m., I woke to a sound that made every hair on my body stand up: scratching. Deep, deliberate scratching against wood—not a branch against a window, but something sharp and hard dragging across the church’s main doors.

I sat up, listening. Long, slow scratches. Pause. Three quick scratches. Silence. Then again: long, slow scratches. Pause. Three quick ones.

I got up, pulled on my robe, grabbed my flashlight, and walked through the dark hallway to the sanctuary. The scratching was louder. It came from the large double doors at the front entrance. I stood in the sanctuary, forty feet from the doors, listening to the pattern. I should have been terrified. Maybe I was. But I was also angry—someone was vandalizing church property.

I walked toward the doors, footsteps echoing. The scratching stopped. I stood in silence, hand on the door handle, flashlight pointed at the worn wood. The doors were old, solid oak. I could see fresh marks—deep gouges that hadn’t been there before.

“Whoever’s out there, this is private property. You need to leave now or I’m calling the sheriff,” I called out.

Silence. Just the wind and the settling of old wood. I waited a minute, then returned to bed. But sleep didn’t come easy. The depth of those scratches, the deliberate pattern, felt wrong.

In daylight, the marks were worse than I’d thought—four parallel gouges, each a quarter inch deep, running vertically down the door from seven feet up. Whatever made them had to be tall and strong. I took photographs and called Sheriff Morrison.

He arrived at noon, a man in his late fifties, sheriff for over twenty years. He examined the doors, took his own photos, and looked for tracks. “Tom,” he said, “I don’t know what made these. Too high up for a person unless they were on a ladder, too deep to do quickly. And there’s no footprints, no ladder marks in the snow. Nothing.”

“Could be a bear,” he suggested. “Sometimes they’ll stand up and scratch at doors if they smell food.”

“No food here,” I said.

“Keep your doors locked. I’ll have a deputy drive by a few times.”

That night, at exactly 3:17 a.m., the scratching came again. Same pattern. I got up, walked to the sanctuary, listened, but didn’t approach the doors. Five minutes, then it stopped.

New scratches in the morning. Eight parallel marks now. I called Morrison again. He sent Fish and Game. They examined the marks, looked for tracks, scat—anything. Nothing.

“These marks don’t match any animal we’re familiar with,” Officer Carter told me. “The spacing is wrong, the depth is wrong, and there’s no sign of animal activity. It’s unusual.”

“Keep your doors and windows locked. Don’t go outside if you hear it.”

Night three, 3:17 a.m. The scratching returned. I didn’t get up, just lay in bed listening. Five minutes, then it stopped. Twelve marks now.

My congregation started to notice. Sunday service, people asked about the damage. I told them about the nightly visitor, leaving out the time and pattern—I didn’t want to frighten anyone. But I was frightened. Whatever was doing this came every night at the exact same time, made the exact same sounds, left the exact same marks. There was intelligence to it—a purpose.

Night four, five, six. By the end of the first week, twenty-eight parallel marks on the door. I stopped going into the sanctuary during the scratching. I just lay in bed, counting the minutes.

Sheriff Morrison came by again. “Tom, I’ve never seen anything like this. Systematic, precise. This isn’t animal behavior.”

“Then what is it?” I asked.

He didn’t answer. “I’m going to station a deputy here tonight. We’ll catch whatever this is.”

Deputy Wilson arrived at midnight, rifle ready, spotlight and radio at hand. At 3:17 a.m., I heard his voice on the walkie-talkie: “Reverend, I’m seeing something. It’s approaching the doors. I’m turning on the spotlight.” Then he screamed—a scream of absolute terror. The spotlight flickered on, illuminating the church. The patrol car engine roared, tires spinning, and the vehicle sped away.

The scratching started. Same pattern. Five minutes, then silence.

Wilson’s patrol car was found abandoned on the highway, driver’s door open, engine running. Wilson was three miles away, walking in shock. He couldn’t speak for hours. When he did, he refused to say what he saw. He resigned the next day and moved out of state.

Morrison came to see me, his face gray. “Tom, whatever’s happening here is beyond us. I don’t have the resources or the courage. I’m sorry.”

“So what am I supposed to do?”

“Pray, I guess. Isn’t that your department?”

Something was coming to my church every night. Something that terrified a trained officer so badly he fled and quit. Something that left marks no animal could explain. Eight nights, twenty-eight marks—four marks per night. Four. The number had significance in biblical numerology: four corners of the earth, four horsemen, four living creatures.

I started researching, pulling out old theological books, reading about supernatural encounters, about things that scratch and knock and wait to be invited in.

Night nine, ten, eleven. By two weeks, fifty-six marks on the door. My congregation was terrified. Families stopped coming. Others suggested we abandon the building. But this was holy ground. I couldn’t abandon it.

I started sleeping during the day, staying awake at night, sitting in the sanctuary, waiting, watching, praying. I’d sit in the front pew with my Bible, reading by candlelight. This was spiritual warfare. I knew that now.

Night fifteen, 3:17 a.m. I was sitting in the sanctuary when the scratching started. I stood up, Bible in hand, and walked toward the doors.

“In the name of Jesus Christ,” I called out, “I command you to leave this place. This is holy ground. You have no power here.”

The scratching stopped for ten seconds. Silence. Then it started again, louder, more aggressive. The doors shook. I backed away. The scratching continued for ten minutes instead of five. When it stopped, I saw fresh gouges, deeper than before. It had responded to my challenge—and it wasn’t leaving.

Night sixteen, seventeen, eighteen. The doors were covered. The wood so damaged I knew they’d need replacing. But I didn’t care about the doors. I cared about what would happen when it ran out of space to mark.

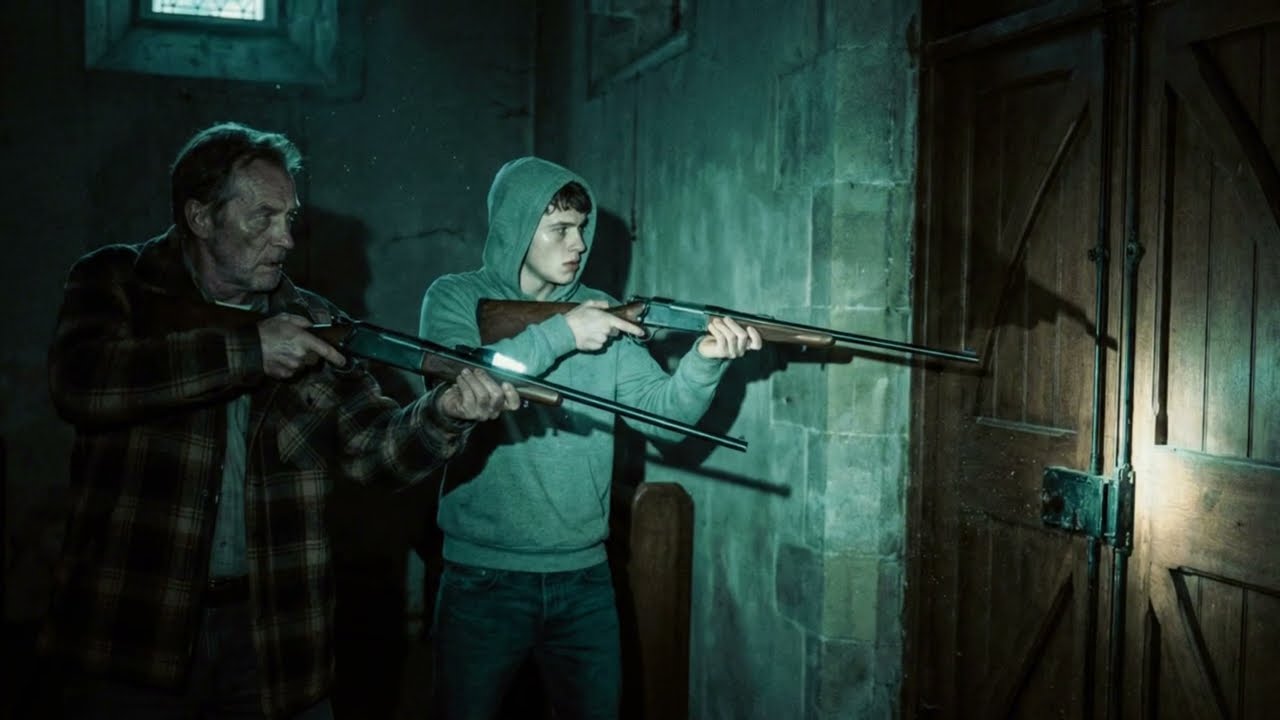

Members of my congregation started staying with me. Robert Chen and his son Michael brought rifles, flashlights, and determination.

“Pastor Tom, whatever this thing is, it needs to know we’re not afraid.”

At 3:17 a.m., the scratching started. Robert and Michael went to the doors, rifles ready.

“We’re armed and we’re not afraid of you. Leave this place,” Robert called.

The scratching stopped. Then a sound—a deep, resonant growl, filled with intelligence and rage. Robert and Michael backed away.

“That wasn’t an animal,” Michael whispered, pale as snow.

The scratching resumed, continued for fifteen minutes. When they left at dawn, both men were changed. “We’re not coming back,” Robert said. “I’m sorry, pastor, but whatever that is, we can’t fight it.”

I stopped eating, stopped sleeping. I just sat in the sanctuary, reading scripture, praying, trying to understand. That’s when I found it—a passage in an old book about frontier religious experiences. A circuit preacher in the 1840s described something he called the knocker, a creature that would visit remote churches, scratching at doors and windows, counting down to some unknown event.

He wrote it appeared as a massive wolf-like creature, walking on two legs, eyes glowing in the dark, claws that could tear through wood and stone. The creature would visit for exactly 27 nights. On the 28th night, it would stop scratching and wait at the doors. If the doors were opened, it would enter and claim the soul of whoever opened them. If the doors remained closed, it would leave and never return.

I counted back. This was night 22. Five more nights of scratching, then the test.

Night 23, 24, 25. The doors were completely covered—hundreds of parallel scratches, each the same depth, spacing, intention.

Night 26. The scratching was all over the building—doors, windows, walls, roof. It sounded like dozens of claws scratching simultaneously, surrounding the church. I sat in the sanctuary, candles burning, Bible in my lap, praying harder than ever. The scratching continued for thirty minutes. When it stopped, the silence was worse than the noise.

Night 27, the final night. I called my daughters, told them I loved them. At 3:17 a.m., the scratching began—so loud it shook the building. Doors rattled, windows vibrated, pictures fell from walls. The sound was overwhelming. At 3:22 a.m., it stopped. Complete silence.

I sat in that silence, knowing what was coming the next night.

November 28th, 1997. The 28th night.

I spent the day preparing. I called Morrison, told him not to come. I called my daughters again. I wrote letters, sealed them, left them on my desk. I cleaned the sanctuary, lit every candle, placed my Bible on the altar, prayed for strength and courage.

As darkness fell, I sat in the front pew and waited. The temperature dropped. My breath came out in clouds. The church creaked and settled. Outside, the wind howled through the pines.

At 3:16 a.m., I heard footsteps—heavy, deliberate, crunching through snow. They circled the building three times, then stopped at the front doors. Silence. I could hear my own heartbeat.

Then, at exactly 3:17 a.m., there was a knock—not a scratch, a knock. Three slow, deliberate knocks.

I stood up, legs shaking, hands trembling, and walked toward the doors. Another three knocks, patient, waiting.

I thought about Wilson running in terror, Robert and Michael backing away, 27 nights of scratching, feeling helpless. I thought about being a pastor, a shepherd, standing between my flock and the wolves.

“You want to come in?” I said, voice steady. “Then come in. But you’re coming into a house of God, into holy ground, to face a man who serves a power greater than whatever you are.”

I opened the doors.

What stood on the other side defied description. Eight feet tall, covered in dark, matted fur, standing on two legs like a man, but the legs bent wrong, jointed impossibly. Arms too long, ending in hands tipped with claws I recognized from the scratches. The face was wolf-like, stretched and wrong, snout too long, teeth too visible, eyes glowing pale yellow-green—not red, but producing their own light. It looked at me with absolute intelligence, more than human.

We stood facing each other across the threshold. It made no move to enter. I made no move to retreat.

“You’ve been scratching at my doors for 27 nights,” I said. “You’ve terrorized my congregation. You’ve damaged God’s house. What do you want?”

It didn’t speak, but I heard a voice in my head—deep, ancient: Permission.

“Permission for what?”

To enter, to take, to claim what is owed.

“Nothing is owed to you. This is holy ground. These are God’s people. You have no claim here.”

Its eyes narrowed. Every night I marked. Every night I counted. The number is complete. The time is fulfilled. Open the way.

“The way is open,” I gestured to the doors. “You can enter, but you enter as a guest under God’s authority, subject to His will. You have no power here except what He allows.”

It tilted its head, studying me. Then it raised one massive clawed hand, reaching toward the threshold. The moment its claw crossed the doorway, the air inside seemed to thicken, resist. The candles flared brighter. The creature pulled its hand back as if burned. It looked at its hand, then at me, and I understood. It couldn’t enter—not because of the doors, but because this was consecrated ground, because faith had power, because I refused to give permission born from fear.

“You counted wrong,” I said. “Twenty-seven nights of scratching. You thought the 28th night was the night of entering, but you forgot something. Twenty-eight days isn’t a completion—it’s a cycle, a test of endurance, not a countdown to surrender.”

The creature stared at me. The voice came again, quieter, almost uncertain: You do not fear.

“I’m terrified,” I admitted. “But fear doesn’t mean surrender. You can scratch every surface, leave a million marks, but you cannot enter unless invited with willing submission. And I don’t submit.”

We stood there for what felt like hours, but was probably minutes. Then the creature stepped back. It looked at me one last time, and I heard the voice: You have passed. Others have not. Others will not.

Then it turned and walked into the forest, disappearing into the darkness with impossible silence.

I stood in the open doorway until dawn. The oppressive feeling lifted. When the sun rose, I closed and locked the doors.

The scratching never returned. The creature never came back, but the marks remained until I replaced the doors six months later. I kept the old doors in the basement—proof, a reminder.

My congregation returned. I never told them the full story. I said the problem had resolved itself. Most accepted that, grateful to return to normal.

But I researched. The old preacher’s story wasn’t unique. Throughout history, across cultures, there are accounts of creatures that knock and scratch, count and mark, test the faith and courage of those who encounter them. Some call them dogmen, skinwalkers, windigos, by a dozen names—but the pattern is always similar. They appear in remote areas, target spiritual sites, test, count, mark. If fear wins, if the door is opened in submission, they enter and take what they came for.

I served at Shepherd’s Grace for another twenty years, then retired. The church continues to serve its community. Life goes on. But I kept those doors. They’re in storage now, proof that the world contains things we don’t understand—things that exist in the spaces between what we know and what we fear.

I’m 71. I’ve spent 27 years carrying the memory of what I saw that night. I’ve questioned my sanity, but I know what I saw. I know what stood at my church doors for 27 nights. I know what I faced on the 28th night. And I know that I passed a test that others failed.

Faith isn’t the absence of fear—it’s refusing to let fear make your decisions. It’s standing in an open doorway, facing something impossible, and saying, “No. Not here. Not today. Not ever.”

The scratches are gone now. The congregation has forgotten. But I remember every detail, every sound, every moment of those 28 nights. And sometimes, late at night when the house is quiet, I hear scratching—not at my door, but in my memory. A reminder that some tests aren’t meant to be forgotten. They’re meant to shape who we become.

I passed the test. But I wonder how many others have faced similar tests and failed—how many remote churches, isolated homes, lonely outposts have heard the scratching and the counting and the waiting, and how many opened their doors in fear instead of faith.

The creature said others would not pass. I believe it. Because facing the impossible requires more than courage—it requires conviction. Some thresholds, once crossed, can never be uncrossed. Some invitations, once given, can never be revoked.

I never opened my door in submission. I opened it in challenge. And that made all the difference.

The 28 nights of winter 1997 changed me. They showed me that faith is tested in darkness, courage measured in terror, and that some shepherds must stand between their flock and the wolves—even when the wolves are more than wolves.

I’m an old man now. I’ve lived a long life, served my calling, raised my daughters, buried my wife, and faced down things that shouldn’t exist. And if I learned anything from those 28 nights, it’s this: When something scratches at your door, counting the nights, marking its claim, remember you have a choice. Fear is natural. Submission is not. Stand your ground, hold your faith, and never, ever invite the darkness in.