An Old Man Saved a Bigfoot Mother and Her Child — Moments Before the Train Arrived.

Would you dare to save a strange bound creature lying across railroad tracks—when your entire town walks away like nothing happened?

Clover Gap, Kentucky, is the kind of place where the mountains hold the sky down low and the hollers keep secrets the way old men keep scars. People here are polite, careful, and practiced at not seeing what they aren’t supposed to see.

That’s why, when the black car rolled in that morning, nobody looked too hard.

It was early spring. The last bite of winter still lived in the shadows, and rain fell steady as needles, slicking the rocks and rusting the rails that cut through the gorge. A single road ran along the ridge like a crack in old bone. Down below, the tracks curved away into fog and pine.

The Lincoln Town Car didn’t belong here. It gleamed like it had never known dust. It stopped on the gravel shoulder just above the tracks, engine idling with a low, patient growl. A man in a tailored suit stepped out. His shoes sank into mud, but he didn’t flinch. He moved like someone who’d never had to answer for a mess.

He opened the trunk.

And dragged out a burlap sack.

It was heavy. It moved.

He dropped it like garbage onto the gravel beside the rails. The thud sounded wet, wrong. He nudged it once with his boot, watched it twitch, then pulled out a second bundle—smaller, lighter—tied the same way.

He didn’t speak. Didn’t look around. Didn’t check whether anyone was watching.

He slammed the trunk and drove off into the fog, leaving the sacks in the rain like he was leaving trash at a dump.

For a full minute, nothing happened.

Then the larger sack shuddered hard, as if something inside had woken up and remembered pain. Claws—dark, cracked—tore at the coarse fabric. The sound that came out was half growl, half plea, and it didn’t belong to any animal people in Clover Gap hunted.

The burlap soaked through, threads weakening. Something ripped free from the torn bottom: a small shape tumbled out onto the gravel and landed hard.

A child.

Not human. Not bear. Not anything the world admitted existed.

It was the size of a toddler, fur plastered to thin ribs, eyes wide and gold in the rain. It blinked up at the gray sky, then looked down the rails.

Far away, the faint scream of a freight train cut the valley like a blade.

The rails began to tremble.

The little one didn’t run.

It scrambled back to the larger sack, tiny hands tugging at knots, biting rope with desperate teeth. A low rumble came from inside the bundle—weak, pained—and the child answered with a thin, frantic cry that made your stomach tighten if you heard it.

Someone did hear it.

Up on the ridge, hidden behind brush, a teenage boy stood frozen. Milo Cade had been skipping school again, smoking behind the trees, practicing the kind of indifference you learn early in poor towns. He’d seen the car arrive. He’d seen the suit. He’d seen the sacks thrown like waste.

Now he watched the small creature claw at ropes while the train’s horn grew louder.

Something in Milo’s chest cracked open.

He stepped forward, then stopped. His hands shook. His brain offered him every excuse: it’s a bear, it’s a trap, it’s not your business. He looked back toward town, toward the safe lie of normal life.

Then he turned and ran.

A second witness passed too—an old pickup clattering down the road. The driver slowed, glanced toward the tracks, saw movement, and looked away so fast it was like his neck hurt. Clover Gap was full of men who could lift engines and fight in bars… but not one of them stopped.

The train was closer now. A headlight curved through mist. The air seemed to vibrate.

And then—beneath the rickety wooden bridge that crossed the creek—a figure appeared, limping out of shadow.

Ernie Barlo didn’t look like a hero.

He was sixty-seven, homeless in the way people become homeless in small towns: not sleeping on sidewalks, but living under bridges, being spoken about in past tense while still breathing. He wore a soaked coat and carried a sack of bottles strapped to his back. His knee dragged him crooked. His beard was weeks old. His eyes were tired.

But when he heard the child cry—sharp, animal, too close to human—he dropped the sack without thinking.

His boots slid on gravel as he scrambled down the embankment.

The train horn wailed again.

Ernie saw the child first, still tugging at the sack. The mother’s arm had fallen free, fur matted with blood. She wasn’t moving.

Ernie didn’t hesitate.

He drew an old folding knife from his pocket—rusted at the hinge, but sharp enough—and dropped to his knees beside the bundle. The child snarled, baring small teeth.

Ernie met its eyes and spoke low, like you speak to a scared dog or a frightened kid.

“I ain’t here to hurt her.”

The child blinked. Rain dripped from its brow.

Then, impossibly, it stepped back.

Ernie sliced rope fast, hands shaking from cold and urgency. The rails trembled hard now. The train’s roar grew into something physical. He wrapped the burlap around his shoulders and pulled.

The weight nearly dragged him down. He fell to one knee, grunted, and hauled again.

The train screamed around the bend.

Ernie dragged the mother off the tracks while the child scrambled beside him, slipping in mud. He rolled into the ditch just as steel thundered past—wind and noise and heat so close it felt like it might peel skin.

For a moment, the world was nothing but train and rain.

Then it was gone.

Silence returned in a single rush, like lungs finally releasing a held breath.

Ernie lay on his back in wet earth, chest heaving. The burlap sack beside him twitched. Slowly, the mother lifted her head.

She looked at him.

Ernie expected fury. Teeth. A blow that would end his life without effort.

Instead, she only looked—deep, tired, battered by something worse than weather. One leg lay twisted wrong. Her breathing rasped. The child crawled into her side, pressing close.

Then she reached out.

A long arm, heavy with pain, moved toward Ernie. Her palm—bloodied, rough, enormous—pressed gently against the center of his chest.

Not force. Not threat.

A quiet thank you.

Ernie forgot to breathe.

The contact was warm, alive. The air between them held a weight older than language.

Then her eyes rolled slightly. She exhaled once and passed out.

Ernie gathered the child into his coat. It didn’t resist. Its small fingers gripped his flannel like it didn’t know what else to hold onto.

Up in the trees beyond the tracks, something watched—tall, still, silent.

Not a man.

Not a deer.

Ernie didn’t look up. He wrapped his arms tighter around the child and sat with his back against rock, eyes locked on the mother’s unmoving chest.

He didn’t know what he’d do next.

But he knew one thing for sure:

He wasn’t leaving them there. Not in that world. Not ever again.

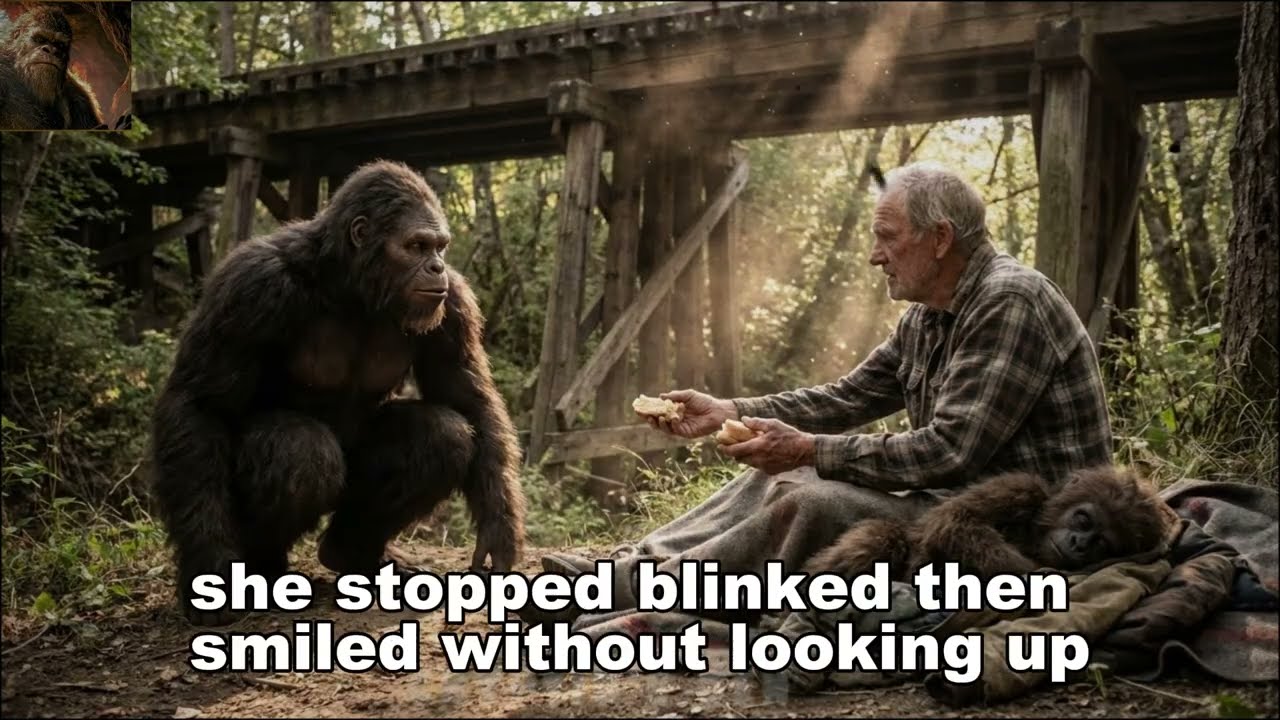

The sun rose late behind the ridge, pale and weak. Under the bridge, the creek whispered around mossy rocks. Ernie woke with the child curled against his ribs, breathing fast like a puppy. The mother sat awake, eyes open, watching him with no rage—only vigilance.

Ernie reached slowly into his satchel and pulled out the last of his bread, stale and cracked. He tore off a piece and held it out.

The child stirred, sniffed, looked at him, then did something that made Ernie’s throat close:

It waited.

No snatching. No panic-grab.

It watched him blink, watched his fingers, as if waiting for permission.

Only when Ernie moved the bread closer did the child take it—gently, careful, chewing slow. Golden eyes stayed fixed on his face like it was memorizing him.

Ernie offered bread to the mother too. She didn’t take it, but she didn’t growl.

Her leg looked worse in daylight. Swollen above the ankle. Fur parted by a jagged wound that smelled wrong—hot, infected. Ernie recognized the shape of it: wire. Snare. The kind poachers used and forgot.

He needed help.

But not the kind of help that came with questions, radios, and guns.

So he left them hidden under the bridge and limped toward the only person he trusted to see something impossible and not try to own it.

Tess Hartley, nurse by trade and by nature, ran a tiny backroom clinic behind the general store. Folks in Clover Gap went to her before they went to the county hospital, because Tess treated people like people, not problems.

When Ernie stepped into her back room, soaked and shaking, she opened her mouth to scold him for his “adventures.”

Then she saw his face.

“I need your help,” he said. “But you can’t ask questions yet. You just… gotta see.”

Tess stared at him for a long moment. Then she grabbed her medical bag.

She followed him into the woods without another word.

Under the bridge, when Tess saw the mother Bigfoot and the child tucked in Ernie’s coat, her breath caught—but she didn’t scream. Didn’t run.

She knelt beside the wounded leg, eyes bright with shock, and whispered, “Oh God… help me.”

Then she opened her bag.

Her hands were steady, even when her voice trembled. She cleaned the wound gently, speaking soft, meaningless comfort the way nurses do when pain is unavoidable. She applied antibiotic cream, wrapped bandages, and—most importantly—she moved like someone who understood body language.

The mother watched her closely.

The child crawled over and placed its small hand on Tess’s forearm.

Tess froze.

Then she smiled, soft and sad, without looking up.

“It’s okay, baby,” she whispered. “I’m just trying to help her.”

When they finished, they sat in the damp hush listening to the creek. Tess packed her supplies slowly.

“I can’t tell anyone,” she said at last. “You know that, right?”

“I wouldn’t ask you to,” Ernie answered.

Tess swallowed. “I could lose everything.”

“I know.”

She looked back at the mother, who had closed her eyes now, breathing calmer. The child had fallen asleep against Ernie’s coat.

Tess exhaled. “I’m not sorry.”

Neither was Ernie.

That night, Tess came back with more bandages, a bottle of antibiotics she shouldn’t have taken, and a blanket thick enough to make the cold bearable.

And that night, Milo Cade came back too.

He approached the bridge like a man walking toward his own shame. He crouched on the far side of the creek, notebook clutched in his hands, face pale.

Ernie noticed him first.

“Boy,” Ernie said without turning. “You got something to say, say it.”

Milo stepped forward inch by inch, staring at the mother and child like they might vanish if he blinked.

“I saw it,” he whispered. “The car. The sacks. I… ran.”

His voice cracked. “I should’ve helped. I’m sorry.”

Ernie stared at him a long time, rain tapping wood overhead. Then he said, quiet and final:

“Wrong’s only permanent if you let it sit there. You came back. That counts.”

Milo wiped his face on his sleeve and sat by the fire like a boy trying to become braver than he’d been yesterday. He opened his notebook and wrote down what he’d already started: the time, the place, and the license plate he’d memorized in panic.

He didn’t know why it mattered.

Not yet.

But Clover Gap has a way of turning “someday” into “too late” if you don’t write things down.

For a while, it almost worked.

Days passed. Tess treated the leg. Ernie brought food—whatever he could scavenge. The child grew less frightened, began to crawl closer to Ernie on its own, sleeping against him as if warmth was something it had almost forgotten existed.

The mother—Ernie called her Sable in his head, because her eyes were dark and her fur had that smoky sheen—watched him like a judge who hadn’t decided whether mercy was safe.

Under that bridge, something like a family formed. Not papers, not blood—choice. A small community held together by quiet acts no one would clap for.

Then danger circled back.

It came in the form of two men with cigarette voices and careless laughter, walking the creek bed with flashlights. Milo heard them first and hissed a warning. Tess’s face went white.

Ernie signaled everyone to stay still.

The voices got closer. Boots crunched gravel.

“Thought I heard something down here,” one man said.

Flashlight beams swept the rocks, searching.

Then—like a shadow deciding it was tired of hiding—Sable stepped forward into the thin light.

She didn’t roar. Didn’t lunge.

She just stood.

Full height. Wounded foot planted. Chest rising slow, controlled.

The men froze. Their voices died mid-breath. Ernie heard the sound of fear sliding into them like cold water.

One muttered, “Nope.”

And they turned around and left without another word.

Milo exhaled so hard he almost laughed from relief.

Ernie stared at Sable as she stepped back into shadow, and he understood something that made his skin prickle:

She hadn’t stepped out to scare them for herself.

She’d stepped out to protect them—Ernie, Tess, Milo—because if those men had come closer, the story would have ended in blood.

Sable could have killed them.

She chose not to.

The next day, another kind of visitor came.

A man in a gray vest, clean and polite, knocked on Ernie’s makeshift lean-to near the edge of town. He spoke with the tone of someone delivering kindness.

“I heard you saved something on the tracks,” he said. “Bless your soul. Folks around here admire that.”

Then he offered Ernie a coat. Money. A trailer hookup. A warm bed. A little respect.

“All you gotta do,” he said, smiling thinly, “is tell folks it was a bear.”

Ernie didn’t yell.

He didn’t even argue.

He just shook his head once.

The man’s smile stayed, but it stopped reaching his eyes.

“Well,” he said. “You’re a proud man. I respect that.”

He walked back to his car and drove straight up the hill toward Vera Langford’s estate.

Everyone in Clover Gap knew Vera Langford.

They just pretended not to.

She lived on the hill in a house too big for this county, owned land nobody remembered selling, and spoke with sugar in her voice and smoke in her eyes. She had the kind of wealth that made laws feel negotiable.

And she hated mess.

Especially the kind of mess that couldn’t be buried.

That week, Tess found an envelope on her porch. Inside was a Polaroid—grainy but clear enough to steal the air from her lungs.

A baby Bigfoot, tied and muzzled, eyes wild.

And next to it, Vera Langford, hand outstretched like she was feeding a dog at a zoo.

No fear. No shame.

Just ownership.

Tess brought the photo to Ernie and didn’t speak at first. Ernie stared at it until his hands stopped trembling.

Then he took his old folding knife—the same dull blade that cut the ropes on the tracks—and set it down on the stump between them.

“I don’t want a war,” he said.

Tess nodded. “But we ain’t pretending we didn’t see what we saw.”

The only reason Clover Gap didn’t swallow the truth whole was because Milo kept writing.

He’d recorded that license plate the first day, ink smeared from rain. He’d kept the notebook hidden like a sin.

Now it became a key.

Deputy Gideon Rusk—young, ambitious, and proud of how tightly he wore his badge—didn’t believe in monsters. He believed in paperwork, in chain of custody, in the way lies always leave a loose thread if you pull hard enough.

He found the thread when he saw the rope.

Thick braid. Red clay. Not from the north road. Not from any farm in town.

He traced shipments. Asked questions. Found a vet receipt that didn’t match any animal listed. Saw a vehicle washed too clean for where it had been.

And when Milo finally showed him the notebook page—time, place, plate—Gideon’s face changed in a way Milo would never forget.

Not disbelief.

Recognition.

The kind that says: I know exactly who can make this disappear.

Gideon went up the hill to Vera’s house and looked her in the eyes.

She smiled and offered sweet tea like she was hosting a fundraiser.

Gideon didn’t drink it.

He left without pressing charges that day, but he walked out knowing something had shifted. And Vera watched him from her doorway without smiling anymore.

Predators recognize when someone has stopped being afraid.

What happened next didn’t happen with sirens and headlines. Clover Gap doesn’t do loud justice. It does quiet.

A warrant. A Tuesday arrest so the town could watch. Charges with words like “unlawful possession” and “illegal sedation,” because nobody in authority wanted to say “Bigfoot” out loud.

Vera didn’t cry. She didn’t scream.

She simply set down her tea and asked for her lawyer.

Ernie testified with one sentence when asked why he stepped onto the tracks.

“I heard crying,” he said. “So I ran.”

That’s what broke the room.

Not proof.

Not pictures.

The simplest reason in the world.

The sentencing wasn’t enough—money still cushions some falls—but the truth was out, and truth doesn’t go back into the burlap sack once it’s torn.

The officials came for Sable and the child soon after—wildlife jackets, tranquilizer equipment, careful faces trying to pretend they were saving “animals.”

Ernie stepped between them and the mother with his arms open.

“If you have to take someone,” he said, voice trembling, “take me first.”

He meant it.

And the mother—Sable—stood behind him, not attacking, not fleeing, letting him be her shield because she’d learned something dangerous:

Sometimes humans can be mercy.

In the end, the officials did something rare: they lowered the gun. They opened a transport crate and stepped back.

Sable walked in on her own.

No force.

No violence.

The child—Kestrel, the name Ernie had given him without knowing why—hesitated, torn between the man who’d saved him and the mother who was his whole world.

He crossed the clearing and pressed his small palm against Ernie’s chest, exactly where Sable had done it the first day.

A farewell.

A promise.

Then he turned and followed his mother into the woods.

They were taken deep—far beyond Clover Gap—where the mountains still had places humans didn’t own.

And when the crate door finally closed and the trucks drove away, the bridge was empty.

The fire went cold.

Ernie sat staring at nothing for a long time, hands in his lap, as if waiting for the world to explain what he’d just lived through.

Tess sat beside him, silent.

Milo closed his notebook.

The creek kept running.

And the mountains—those old, indifferent mountains—did something strange that day.

They felt less indifferent.

Because a line had been crossed.

Not by blood, not by law.

By choice.

And Clover Gap would never be able to un-know what it knew.

Years later, people would still argue over whether Bigfoot exist.

Whether the story was exaggerated.

Whether Ernie Barlo was a fool or a saint.

But in Clover Gap, the ones who were there remembered a simpler truth:

A train was coming.

Everyone walked away.

One man ran toward the crying.

And somewhere out in the trees, a mother and her child survived—because compassion, once offered, doesn’t vanish.

It lingers.

Like footprints in wet clay.

Like a handprint on your chest.

Like a mountain town learning—too late, maybe, but not too late to matter—that what you protect says more about you than what you conquer.